By Prof. Assoc. Dr. Gjergj P. Titani

Part Two

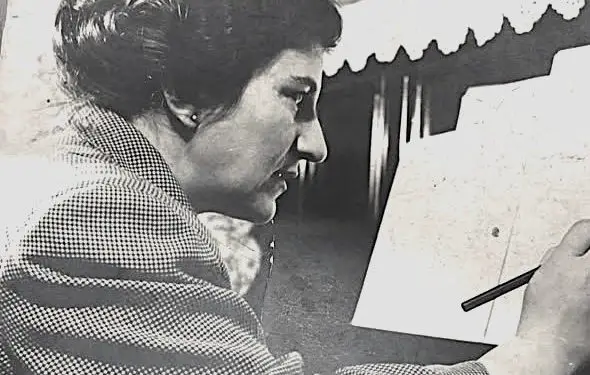

Memorie.al / Starting with this issue, we are publishing a long interview with the “Artist of the People” and “Great Master of Labor,” the distinguished composer Dhora Leka. The conversation with her began a long time ago, but almost nothing has been published because her wish was to finish her memoirs, summarizing them in a special book titled; “Moments and Impressions from My Life.” The book has been reworked several times and has been cross-referenced with both archival documents and her personal family archive. Today we are publishing the first introduction to the distinguished composer, which will continue for several issues.

THE FAMOUS ARTIST WHO WAS SENTENCED TO DEATH

Continued from the previous issue

Ms. Dhora, when did you join the Communist Youth Group?

When Naxhije Dume came to Korça, she lived in a loft, a loft where many illegal activists found shelter in turn, where wax sheets for communiques were printed, and where we kept the trigger of a Nagan revolver cocked under a pillow. It was in that loft that I would compose my first song, “The Call to Arms”! The future writer Fatmir Gjata was also part of the anti-fascist youth core in Korça.

In those years, he had also started writing his first poems. One day he read some of his poems to me, and that’s how the fervent collaboration on partisan songs was born, such as: “The Cry of Liberation,” “The Old Man and the Young One,” “Hymn of the Albanian Anti-Fascist Youth” (Youth, Youth), “The Song for the Martyr Kristo Isak,” “Revenge,” “How the Partisans Fight” (Those striped peaks), and others. In September 1942, I was appointed as a teacher in the elementary school of the village of Plasë, along with my brother, Petro.

The village was about a two-hour walk from the city of Korça. But I was only a teacher in name. The bulk of the teaching work was done by my brother, Petro, who was also a participant in the National Liberation Anti-Fascist Movement. I, on the other hand, was primarily devoted to the illegal activity of the war for freedom. I paid special attention to composing songs. So, from August to December 1942, I composed the songs “The Cry of Liberation” and “Youth, Youth,” both poems by Fatmir Gjata.

How did you make the partisan songs?

In early December, I went on duty to the “Devoll Platoon.” It was the first time I met partisans. I taught the platoon’s partisans the song “The Cry of Liberation,” which I had just composed. And not even three months would pass when, in a clash with Italian fascist forces on March 7, 1943, in the village of Hoçisht in Devoll, the first martyrs of the platoon fell: Commander Fuat Babani, Demir Pogri, and little Todi, as they called Todi, from the village of Boboshtica in Korça.

Demka (Demir) had his family in Korça. To defy the fascist occupier, we brought the body of the killed partisan to be buried in Korça. The funeral turned into a powerful demonstration that even led to a clash in the cemeteries; the demonstrators were fired upon by tanks, but the revolt continued in the streets as well. Immediately after the demonstration, they gathered at the house of Agron Frashëri, a determined anti-fascist. There, Fatmir Gjata immediately wrote the verses of “Revenge,” while I composed the melody.

A week later, in a demonstration through the streets of Korça, the song “Revenge, youth, the martyr is calling” echoed. The song “Revenge” was one of the most widespread songs and was sung in the most diverse circumstances. When the “Revenge” battalion was formed with partisans from the Kolonja district, they had the song “Revenge” as the battalion’s anthem.

When the “Revenge” battalion and other forces like the “Fuat Babani” battalion and other ground forces first liberated the city of Leskovik (June 1943), there is a very beautiful episode: A group of partisans, after liberating the city’s post office, told the central operator to connect them by phone to the city of Korça. I was with the “Revenge” partisans.

The central operator, seeing what was happening, connected us to Korça. And do you know what we did?! We picked up the receiver, huddled together, and started singing the song “Revenge, youth.” As we were told later, the entire city of Korça heard the concert we gave over the phone receiver, and it was the best response to the news spread by the fascists that the partisans had supposedly been annihilated in those battles. “Revenge” became not only a song of attack. With “Revenge,” fallen partisan comrades were buried, because it embodied all the hatred against the occupier.

The new partisan songs had to be sung all over Albania. There was a need for them to be written down with musical notes. But I didn’t know how to write my songs in musical notes myself! It was the beginning of 1943. Kristo Kono lived near my house. In those years, he was a music teacher at the Korça Lyceum (later he became a well-known composer). At that time, I was living almost like an illegal activist and only circulated in the city at night. One evening I knocked on the professor’s door. His sister, “Maqka,” came out. I told her I wanted to see the professor.

“These are dangerous things,” she replied when I told her why I was knocking on his door. I was forced to knock on the door of Boris Plumbi. He was a student at the Korça Lyceum. But he had learned to play the piano from a young age from a French professor, a lyceum teacher named Vinkler. For three days in a row, he sheltered me in his house. I would sing the songs, and he would write them down in notes according to the keyboard. And to think that his family was not connected to the National Liberation Movement at that time, though they were later.

I took the songs written in notes to Tirana. I traveled with a fake ID card. I went to Gjikë Kuqali’s house. He took me to a house next to his, at Andromaqi Afezolli’s, an illegal base. And there, for the first time, I met the illegal activist Nako Spiro, a youth leader. It was an emotional meeting! He greatly valued the importance of the partisan songs. In the first days of April 1943, the fascist occupier carried out a massive reprisal in Korça. Entire neighborhoods were surrounded. Hundreds of houses were checked.

Staying in the city became difficult for illegal activists, so I, like many others, had to leave the city of Korça. First in the Korça plain, then in the villages of Rrëza, and later in Voskopojë and Vithkuq, where there were important bases of the Anti-Fascist War. In Voskopojë, in the monastery of Shën-Prodhomi, a very old monastery, famous all around for the small miraculous church of Shën-Prodhomi, in July 1943, I met Enver Hoxha for the first time! He stood out from the other fighters because he was very well-dressed, with a Turkish ten-piece revolver on his belt with a cord hanging from his neck to his belt, and he was very charming!

How do you remember the beginning of your work at Radio-Tirana?

My beginnings at Radio Tirana were as enthusiastic and beautiful as they were difficult. This was because I had no idea what kind of work I would be doing. In this regard, Islam Proseku helped me a lot; he knew every name of the discs and their place in the record collection. He was an early employee of this institution in that role. Every day I would draft the musical programs that I would broadcast the next day and throughout the week. Here is an example of my musical and professional ignorance.

One day, the respected professor, Mihal Ciko, who had been the head of music at Radio-Tirana for years, came into my office worried and said to me: “Dhora, do you know how this disc you’ve put in the program, which is conducted by the great conductor Toscanini, begins?” “No, I don’t,” I said. “Well, I’ll tell you where the flaw is. The concert on this disc opens with the Nazi anthem ‘Deutschland über alles’.” This would have been a real scandal! That’s who I was in those first years after liberation. I felt very embarrassed and from that moment on, I made it my duty to study music. This was my dream.

I realized that composing partisan songs was not enough; I had to fundamentally know and study music, art history, musical notation, harmony – everything. I worked at Radio-Tirana until I left for the Soviet Union for my studies. I was part of the first group of students who left for the Soviet Union. This group initially went to Moscow, and the fields of study were divided there.

I was assigned to the Leningrad Conservatory. I began my studies there, but I couldn’t handle the harsh climate of Leningrad, and the doctors recommended that I return to my homeland. I continued working at Radio-Tirana until 1948, when I left again for the “Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky” Moscow Conservatory to continue my studies.

What happened next?

Exactly what I had dreamed of for years happened. I started my music studies.

How were you accepted into the Conservatory? How did you handle the admission committee’s requirements?

On the appointed day, I appeared before the admissions committee. I knew very little Russian. The committee chairman addressed me with gestures, motioning for me to sit on a chair near the piano, and placed a musical score in front of me. I shrugged my shoulders, making them understand that I didn’t know anything. The committee asked me several questions that I again didn’t understand. Finally, they asked me why I had come to the Conservatory. And I answered with the only word I knew: “uchitsya” (to learn), and with the few words I knew, I told them that during the war I had composed songs, war songs.

And suddenly, another question. I started singing some of my partisan songs. When I finished singing, the committee members burst into applause, and the chairman of the committee said in their language: “Otlichno, otlichno” (Excellent, excellent), you are accepted.” After this difficult trial, a special program was drawn up for my studies, which lasted five years. I was very lucky that I was assigned the best professors from one of the most renowned Conservatories in the world. So, in November 1953, I defended my diploma with my four-movement symphonic cantata titled; “Albania, My Homeland,” which was performed by the Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra.

In the following years at this Conservatory, many other students continued their studies, such as: Tish Daia, Çesk Zadeja, Lluk Kaçaj, Avni Mula, Ibrahim Tukiçi, Rifat Teqja, Hamide Stringa, and many others whom I can’t recall at the moment. They were a brilliant generation that gave an unprecedented impetus to Albanian musical culture, and some of them still shine today. In the first group that went to the Soviet Union, I was the only girl and would study music.

The others were: Stefanaq Pollo, Fatmir Gjata, Llazar Siliqi, Alfred Uçi, Zija Xholi, Arben Puto, and many others who would study in different fields, but whom I cannot recall at the moment. When I started my studies at the Conservatory, only the tenor Maliq Herri was with me, while in later years, many students studied at the Conservatory, who were lucky enough to become prominent personalities.

What can you tell us about your personal life at the Conservatory?

Besides my studies, an important event in my life was meeting and marrying Çesk Zadeja. My acquaintance with him happened in Tirana in 1949, when I was on summer vacation. This acquaintance was very coincidental. At a meeting where I met the “Artist of the People,” the talented and passionate conductor of the Army Artistic Ensemble, Gaqo Avrazi, I was introduced to a soldier from the ensemble. Gaqo introduced me to the Ensemble’s pianist, Çesk Zadeja, and told me that he also composed. He impressed me a lot.

When the Army Ensemble came for a tour in Moscow in December 1949, I was assigned by the Ministry of Culture of the Soviet Union to accompany the Army Ensemble and present in Albanian at various concerts. During these days, I became friends with Çesk. Afterward, I did my best to get him a scholarship to study in the Soviet Union. After many efforts, this goal was also realized, and Çesk came to Moscow to study. It was in Moscow that we got married. From this marriage, we had a beautiful child, a son, but unfortunately, this child did not survive and died a few days after birth.

How did your life continue after that? Did you have other children?

No, we did not have other children because the dictatorship made it so that this marriage would not last. We separated when I was interned in Gjirokastër and later when I was imprisoned. But, surprisingly, after the democratic processes and the overthrow of the dictatorship, Çesk and I remained friends, and I believe I have fulfilled my civic duty towards him and his family. This very sincere friendship continues even today with the family of Çesk Zadeja, this great composer.

Anyway, what can you tell us about the political situation on the eve of the Albanian Communist Party Conference in Tirana in April 1956?

First, I want to emphasize that I have definitively broken away from politics. But still, I cannot say that I am an apolitical person, otherwise how can you explain all that long and fierce persecution of the dictatorship against me and my sister’s family? Upon my return to Tirana, I was appointed a teacher at the “Jordan Misja” Artistic Lyceum, and in February ’54, at the general conference of the country’s Artists, I was elected General Secretary of the League of Artists of Albania, and the well-known painter, Foto Stamo, was elected Chairman. At the same time, I continued to be a teacher at the Lyceum.

I remember the beginning and the continuation of my work at the Lyceum. It was a very interesting activity that I loved with all my heart, because I was teaching talented young people what I had dreamed of and learned at the Moscow Conservatory. The subjects I taught were Harmony and Musical Literature, which I illustrated for the students with concrete didactic tools and with the discs I had brought from Moscow. I remember my students, who listened to me with devotion and who still greet me with warmth today, among which I can mention Robert Radoja, the pianist Margarita Kristidhi, Gaqo Çako, etc.

This was, in short, the situation on the eve of the development of this Conference, which, along with other intellectual comrades, also condemned me. When Stalin died, I was in Moscow. Not long after, jokes started circulating (and jokes are like those swallows that herald the coming of spring). The protagonist was Stalin, but not the “Great” Stalin. Then came the XX Congress. The ice was broken! And the time came when, after 35 years, even in our Albania, Stalin would finally be overthrown from his pedestal. Dictators, whatever they may have been, white, red, yellow, black, have one end: Shame!

To speak in ’55-’56, or later, about the cult of Stalin, you would be labeled: anti-Soviet; an enemy of the Party at a time when the Soviet country itself was accusing Stalin of horrific crimes and as a dictator. The question naturally arises: What about the cult of Enver Hoxha? Was it not sung then by a polyphonic group; “In Albania, neither the Sun nor the Moon shines / Enver Hoxha has taken their place.”

And no one thought at all that by taking the place of the Sun and the Moon, an Eclipse occurs, darkness covers everything; that no matter how much a person shines, even if they are a giant, they cannot replace the full-shining sun, or the dimly-lit moon, or even a simple spotlight. This is how these deeds of that time come to my timid memory, even as I talk to you today.

What is your opinion of the events of those days, Ms. Dhora?

As always, the first to become aware was the Albanian intelligence. And it happened that all these deeply negative phenomena that were being paralleled did not fail to be reflected in a party conference, such as the one in Tirana, held on April 14, 1956, which, due to the importance of the issues presented, surpassed an ordinary Congress.

This whole trend of breathing freely was happening in Albania then when the 1956 Revolution had not yet erupted in Hungary, which was far from the “Prague Spring,” much further from “Solidarity” in Poland, and still very, very far from the time that brought Mikhail Gorbachev to the head of the Soviet Union, who let the warm winds of the West blow in the East as well.

Similar reflections occurred both before and after the Tirana party conference, also in the League of Writers and the League of Artists of Albania. It is enough to mention that the basic organization of the two Leagues tasked its delegate to the conference (Dhimitër Shuteriqi) to present these views at this Conference, which he did not do. / Memorie.al