By Dr. Nikol Loka

The third part

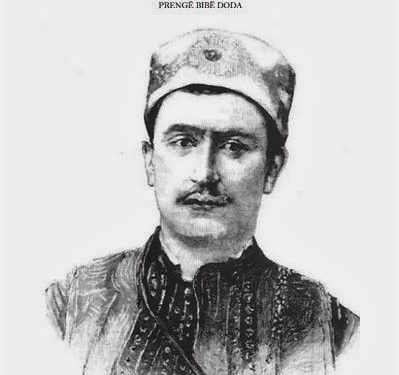

“PRENGA BIBE DODA, THE SHADOWS OF A CITIZENSHIP”

Memorie.al / The newest book “Prengë Bibë Doda, a phenomenon in Albanian political life”, by the researcher Nikollë Loka, not only expands the field of historical studies on Mirdita, the Door of Gjonmarkaj and the figure of the Mirdita Prince, Prengë Bibë Doda, but it is also a contribution to national historiography. The very rich archival material, the literature used or consulted, oral traditions, etc., make this book a real study treasure, giving the science of history a scientific monograph that enriches our knowledge of Mirdita, its captains, tradition, history etc. To study such an important and complex figure, as the figure of Prengë Biba Doda, is a high scientific responsibility that not everyone undertakes. Nikollë Loka, has done a great job of research and treatment by the professional researcher, giving us the portrait of the Prince and the general Mirditor, with the true contours. Loka has adhered to the end of space and time, in which the multidimensional events and their protagonists have unfolded.

THE MONOGRAPH “ABOUT BIBË DODA, A PHENOMENON IN ALBANIAN POLITICAL LIFE”, A VALUABLE SCIENTIFIC STUDY THAT ENRICHS THE FUND OF OUR HISTORICAL STUDIES

(By Mr. Sc. Murat Ajvazi, March 2017, Switzerland)

Continues from last issue

After his murder, Turkish officers were appointed to that position, which were forced to stay in Mjeda. From the salname of the Shkodra Vilayet, from 1897, we learn that the Mirdita zapti battalion consisted of five companies with fourteen officers in the corps, of which nine were Mirdita. In 1889, there were small groups of zaptiyas in Bajrak, who were considered the eyes and ears of the government. (29)

For their maintenance, 8,000 grosh were spent per year. They received their salaries once every three months in Shkodër, but often very late and, under those conditions, they often turned from being keepers of order into robbers. The occupations in that period of extreme poverty enjoyed economic benefits, while their officers, even greater benefits, therefore lured by the payment that was given to them, some well-known leaders were also engaged in the close departments, among them the chieftain of Fan and of Spaçi, they became sub-lieutenants. In 1895, the zapties that operated in the Ohrid bajraks, stayed in Fushë te Lumthi. (30)

The transition of some leaders and chieftains to the military structures commanded directly by the Ottoman authorities was another blow to Mirdita’s autonomy. According to a letter from the Ministry of Finance, in 1863, the Captain of Mirdita was given an additional 50 loads of grain, for the payment of the gendarmes’ salaries. (31)

In order to attract the leaders to government functions, their remuneration was set. Initially, the payment was made in a natural way. With the farm, Biba Doda and his descendants were given the right to an annual rent of 100 loads of corn, from the tenth paid to the state, from the province of Zadrima, which was divided: seventy went to Kapidan and thirty, the elders of the five bajraks. (32)

In an attempt to attack the autonomy of Mirdita, it was the appointment of the chiefs in the functions that belonged to them with the Kanun. Thus, in 1867, when Bibë Doda was in Prizren, the Valiu of Shkodra wrote to Kapidani to appoint his deputy, Marka Gjoni. (33)

The captain of the Mirdita was obliged to cooperate with the Ottoman authorities for the performance of his duties. He answered to the ruler of Shkodra for administrative and political activity. As a kaymekam, he enjoyed the highest position, he convened the provincial assembly in Shpal and presided over it, but he was known by the chiefs as Kapidan and for everything, he decided with the Kanun, so nothing was decided without the consent of the chiefs and minors. According to the Canon, Gjomarku had no right to punish anyone without the decision of the assembly.

On August 18, 1861, Bibë Doda wrote to Serxherda of Xibal in Shkodër: “These five mirdites, who are your lordships,… I have you as a friend, I have you as my friend who has already done his work, how can I be more lucky, don’t leave me late”.

In that period, there were various conflicts over fields, pastures, meadows, etc., which created confusion and quarrels. Sometimes, there were armed fights for pastures, such as the one between Isniq and Deçan, in the castles of Peja and Gjakova, which lasted a long time. We recognize a statement, signed by the Bajraktars and the Captain of Mirdita, on April 16, 1867, after the agreement reached between the representatives of the Great Highlands and Mirdita, which was sent to the Vali of Shkodra, Ismail Pasha.

When the conflicts were difficult to resolve with the head and elders, the mountains gathered in a general assembly, they decided the oath of the zabit among the Bajraks, which began on the Day of Sums, until Shënkoll. Whoever acted against the decisions taken was expelled from the country and fined six bags. (34)

THE TRIBES OF OROSHI

Based on historical evidence, it turns out that even the tribes of Oroshi do not come from a common ancestor. Thus, the Skana, Qyqja, Luli and Bushi brotherhoods, which are considered the oldest in Orosh, according to the elders, are earlier, as Rrok Zojzi rightly notes, of completely different origins and are not at all close in origin theirs with other tribes. (35)

On the other hand, in some tribes even within them there are families that do not come from the same trunk and these may be residents who were found in that settlement and merged with the newcomers. It is possible that families derived from other tribes have been internalized within a certain tribe. The settlements formed as territorial communities are made up of different tribes, due to economic conditions, land needs and internal movements. (36)

The legal right in the Leka Canon provides for support or fusion with another tribe. “Coming house, they have a place in the village, they are in his neighborhood, when the village accepts them “the brother of the village”. (37)

Almost every tribe had in its bosom one or more other smaller, supported tribes. Indeed, there were twice as many tribes in Orosh; count to twenty-nine. We have Dedaj, literally from Oroshi, as the head of the country; we also have Dedaj, supported. The same could be said about Cokajt, Markolajt and so on. The Rrehnas tribe is also counted as a tribe, despite the fact that it also includes Kadel, Tirta and Pergjivuka, which are considered supported. Even the Qefallars are considered a tribe, although Baloj, Llusku, and Kaçi also go with them. (38) In the same way, the Luli tribe relies on Markolaj and Choku on Dedaj. (39)

The Dedaj of Oroshi, who are held as a family, a great door, as an ancient head in this Dhé, have several branches supported by them, such as the Lalaj, the Rrehnaks and so on, that is, they came later to this settlement. A branch of the Lalaj of Oroshi, has moved once and settled in Vela e Vendi, in the Dheu of the Highlands of Lezha. Similarly, Çoku i Oroshi, consists of a local branch, Pal Çoku e Çokaj e Lajthiza and, on the other hand, supported branches, coming from Korthpula e Dibrri and, from Pulaj e Selita.

The different layers have never damaged the provincial, social and coexistence unity. The social and territorial conditions, together with strong rules of the canon, have been integrating, equalizing and balancing factors of this province”. (40)

Some families may be descended from daughters of that tribe whose children were accepted into the tribe. Those who rely on a particular tribe create relationships that last through time, through godship or brotherhood (drinking blood). Whereas, in the case when the children of sissies are accepted in the village, the blood ties exist and in this case, more often, fusion takes place within the uncle’s tribe. The Tirtajs of Oroshi are of two branches: one local, the other coming from Djuxha e Fani, as grandson and daughter, supported by the first branch. They are relatives of the Chetays, of Fani. In the new settlement, the toponyms of the old name, which they had when they arrived, are preserved, such as: Kodra e Ceta, Laku i Ceta, Proroska e Četa, etc. Later, the surname changed, but the early toponyms of the origin remained in the place where they stuck. It is said that he came and settled there, as a nephew from a daughter. (41)

There have been rare cases, when the newcomer has maintained the status of a friend in a settlement and has taken a girl as a gift, with the locals, as Totrri of Shëmrie i Oroshi did, who arrived not too long ago from Kthella. Settled in Orosh, for more than 150 years, he has maintained marital relations with Orosh residents, which has generally not happened with other newcomers. The tribes of Oroshi have not only accepted newcomers, but their separate families have left and have undergone adaptation in the new settlements. In the nine “Mountains” of Dibra, as well as in its plain, there are population groups, however few, originating from Mirdita. Vllaznia Kaza, located in Shumbat te Ujë e m’Ujës, is descended from Oroshi i Mirdita. We note that the Çoku family, living in Muhurr, is of early origin from Oroshi. (42)

In the same way, in Zalle-Dardhë, the Murati family is related to Chok in Orosh, and they came from there. The formation of Oroshi as a village is related to Catholic Hill. Mashtërkorve Hill, which was created by the house of Skanes, which later fell into today’s Mashtërkorve, also served as a residential center…! On that hill, the inhabitants had found furnaces for smelting metals, from the time of the Pyrusts. The remains of slag are still found today, that’s why they called that place; “Hill of the Masters”.

Oroshi is an exception from the other Bajraks of Mirdita, because there are no members of the same tribe, gathered in a particular neighborhood or village, but scattered in several villages. The only division in Orosh is between eighty and fifty houses. This division was so pronounced that once upon a time, when people met an old woman, the first question they asked was: Are you in your eighties or in your fifties?! When the population increased a lot, several were created from one settlement, but care was taken that the tribes of the eighty houses and the fifty houses each formed their own settlements. Thus, the villages were formed from the eighty houses: Grykë Orosh, Bulshar, Ndrshene, while the villages were formed from the fifty houses; Lgjin, Mastrekora e Zajs. This division has not been preserved in some villages of lower Oroshi. Each group had six tribes and therefore six elders.

Having little land, Oroshi, with the passage of time, extended to the winter areas of this land, down to Bukmira, Qafëmolle, Livadhes, Ndreffusazi and half of Spërdhaze village. Between Upper Oroshi (place of origin) and Lower Oroshi, which was also called Dheu i Poštër i Oroshi, is Dheu (bajrak) of Kushnen, located far from the village community of Oroshi. This means that; cattle wintering places; at the beginning, they had not belonged to Oroshi, but had been acquired later, by purchase or donation.

The population from Oroshi settled permanently even in the mountains, which were once used only as places for harvesting. The sub-sites of Lajthiza, which later turned into inhabited villages, were once only summer cottages. (43)

The population from Oroshi settled in the northernmost parts of Mirdita. Thus, Kryeziu i Puka was populated with families coming from Oroshi i Mirdita, from Spaçi, Gojani and Fani. At the time when Ami Bué visited this place, in the thirties of the 19th century, the vast majority of its population was Mirdita, and that village, after the 60s of the 20th century, was administratively divided into two villages: one with the name Kryezi e, the other with the name Orosh, which shows that in this village, the population originating from Orosh prevailed. (44)

The six tribes of the eighty houses are: Markolajt, Dedajt, Dodajt, Dragjosh, Qefallar, Renas. These six tribes consist of the following clans: Markolajt: Gjomarkajt, Bushi, Bajraktari, Topalli, Luli, Curri, Marëpërndrecajt, of Gjokë Llesh Doda. Bushi, is the first of the tribe.

Dedajt includes the following vowels: Kola e Djuta, Lalajt, Dodë Gjin Ndojt, Vukajt, Gjoci, Kaleci, Preng Nikoll Preçit, Bardhok Marka Gjokë Përloshi. The first of the tribe is Kola the Long.

The Deday tribe consists of the following clans: Ndue Bibë Ndojt, Kolë Zezt, Ndre Lleshi, Suti, Gjon Skurti, Zhaba and Zhupi. These last three live in Bukmira and Spërdhaze. The first of the tribe is Ndue Bibë Ndoj.

The Dragjoshes are made up of the following clans: Pjeter Marka Prengës, Llesh Kolë Markut, Preng Ndue Gjinit, Valaneca, Prengë Gjok Deda (Sërrisht) and Margini. The first of the tribe is Llesh Kolë Marku.

The Qefallare tribe consists of the following clans: Baloj, Llusku, Kaçi, Gjok Kol Pasha and Latoshi. The first of the tribe is Latoshi.

In the tribe of Renasi, there are the following clans: Përbašajt, Kadelajt, Rregji, Marka Kol Gjeçit, Preçajt, Shkurt Preng Dede, the first of the tribe, Preng Gjok Dodë Alia. This noise has come out completely. A close substitute is the Kole Gjeçi brand. As whole, as tribes and supported tribes, they are:

Markolaj, Dedaj, Dodaj, Lulaj, Bushi, Topallaj, Qefallare, Rethnaj, Dragosh, Lluskaj, Kaçi, Baloj, Vukaj, Gjocaj, Ndremenaj, Gjivukaj, Tirrtja, Çoku, Kolziu (Kaziu), Xhaferraj, Skana, Gjoprenaj, Markaj, Marpepaj , Sinanaj, Kokaj, Čunaj, Kotica, Kolgjecaj, Brungaj, Perlekaj.

The tribes of the fifty houses are six: Gegedodajt, Sinani, Skana, Koka, Xhaferri and Gjon Prenajt.

In Gegëdodaj, the brotherhoods enter: Ndrecë Marka Gegës, Çuni, Marka Ndrec Prengës and Ndue Llesh Nokës.

Sinanajt: Ndue Prengë Marka Nikollë Gjetë, Llesh Prengë, Brunga and Kotica.

Skana, where Skana himself, Çoku, Bardhoci, Nikollë Prengë Biba are members.

Koka, which includes Tuc Nikolli, Ndue Dodë Kaza, Bibë Gjoka, Çup Ndojt, Shyti.

Xhaferri, where Llesh Marka Gjergjit, Ndue Kolë Pjetrit, Shkurt Nikolli, Vokrri, and Pjeter Prenga are part of.

Gjonprenaj, which includes Marka Ndue Lleshi, Nikollë Prengë Ndreca, Ndreaj, Gjetë Gegë, Bibi Prengë and Gjon Marka Bibi. (45)

It seems that the twofold division of Oroshi’s tribes expresses closeness in tribal ties. The six tribes, within the grouping called the; “eighty spives”, or of; “fifty spives”, feel closer to each other than to the six tribes of the other grouping. The “eighty houses” were located in today’s Grykë Oroshin, which started at the end of Lmaçe, where the eight-year school is today, and ended at the head of the village at the tower of Ndue Dede Marka Kola. According to the saying passed down through the generations, the “eighty houses” were located next to each other, so that, if a cat started from the end of the village, it would arrive at the top, one by one, without ever landing on the ground. While the “fifty houses” of Oroshi are located below, in the valley of Fan e Vogël.

The elders and heads of a tribal unit had two functions: firstly, that of putting discipline and order in the kinship organization, where they lead, and secondly, the protection of his interests, in the bajrak and in the village. So, in a country where there were no judges and state police recognized by the people, the “governance” of the tribal unit, be it family, brotherhood or gender, was completely in their hands. They had to act in accordance with the principles; “according to which a good elder should lead his family community”. (46) Memorie.al

The next issue follows

- Kahreman Ulqini, Structure of traditional society… p.147

- Kahreman Ulqini, Structure of traditional society … p.148

- AQSH, Bibë Doda, file 4, p. 1

- Hyacinthe Hecquard, History and description of Upper Albania or Gegëria, Plejad, Tirana 2008, p. 222

- AQSH, Fund 132, file 5, p.5

- Hecquard, History and description of Upper Albania or Gegëria, p. 374.

- Mark Tirta, Mirdita e mochme e migrime … p. 36-37

- Prelë Milani, Shoshi, Geography, genealogy, history…, p. 209

- Xhemal Meçi, The Canon of Lekë Dukagjin in the variant of Mirdita, “Geer” publications, Tirana 2002, p. 99

- Pal Doçi, Data on the self-government of Mirdita, Historical Studies, year XXVIII (XI), No.3, Tirana 1974, p.103

- Kahreman Ulqini, Structure of society… p. 57

- Mark Tirta, Mirdita e mochme e migrime… p.85

- Mark Tirta, Mirdita e mochme e migrime… p.22-23

- Mark Tirta, Mirdita e mochme e migrime… p. 32

- Mark Tirta, Mirdita e mochme e migrime… p. 24

- Mark Tirta, Mirdita e mochme e migrime… p.25

- Ndue Skana, Skanajt e Mirdita, editions “Geer”, Tirana 2006 46. Walther Peinsipp, The People of Albanians of the Mountain, editions “Mirdita”, Tirana 2005, p. 63

![“When the camp commander, in the presence of the group accompanying him, said to the convicted journalist: ‘Why did you exchange this beautiful profession for the Spaç wagon [mine cart/labor], he [the journalist]…”/ The unknown story of January 10, 1983](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Spaç_Prison_Mirditë_Albania_–_Buildings_2018_08-350x250.jpg)