Part Seven

Excerpts from the book: ‘ALIZOT EMIRI – The Man, a Library and Noble Wit’

A FEW WORDS AS AN INTRODUCTION

Memorie.al / Whenever we, Alizot’s children, told “Zote’s” (Alizot’s) stories in joyful social settings, we were often asked: “Have you written them down? No! What a shame, they will be lost…! Who should do it?” And we felt increasingly guilty. If it had to be done, we were the ones who should do it. But could we write them?! “Not everyone who knows how to read and write can write books,” Zote would say whenever he leafed through poorly written books. While discussing this “obligation” – this Book – among ourselves, we children of Zote naturally felt a sense of inadequacy in fulfilling it. It wasn’t a job for us! By Zote’s “yardstick,” we were incapable of writing this book.

Continued from the last issue

– IMPRESSIONS AND MEMORIES OF ALIZOT EMIRI –

GAQO VESHI (“HYSKE BOROBOJKA”)

THE ENCYCLOPEDIC BOOKSELLER

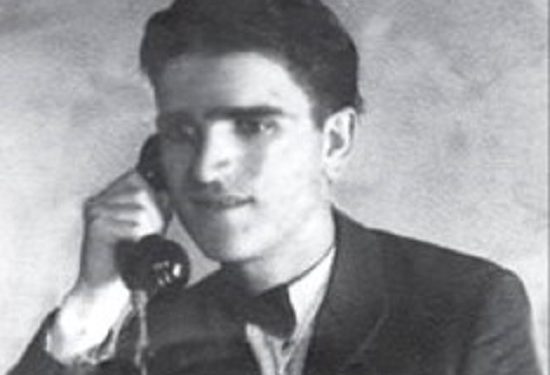

In memory of bookseller Alizot Emiri

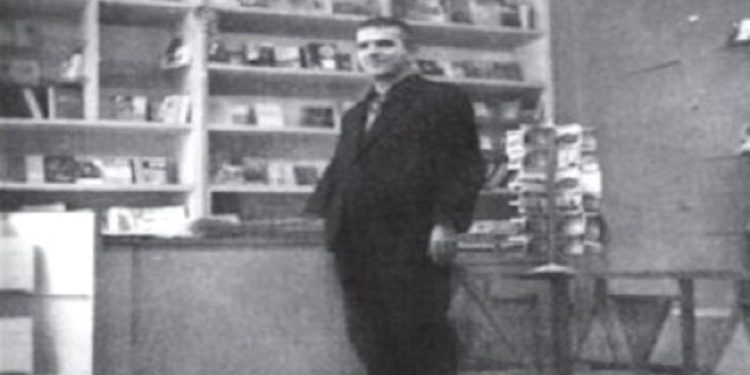

When I see books being sold today on sidewalks and curbs, like onions, tomatoes, apples, or cabbages, I remember as if it were today – many years ago – when I served as an editor for the magazine “Hosteni.” I would go on assignment to the “Stone City” of Gjirokastra, and as I walked down from “Qafa e Pazarit” toward “Sheshi i Çerçizit,” on the right side of the road, there was a simple bookstore that all the locals called “Alizoti’s Bookstore.” It had taken this name because an elderly man, Alizot Emiri, served as the clerk there.

This bookseller was like no other in the entire country I had traveled. From North to South, you could not find his equal. To anyone who crossed the threshold of the bookstore, whether to buy or just to browse, the seller would provide explanations about the content of all the books placed on the shelves, so much so that you would ask yourself: “Has this man read this entire mountain of books, that he explains to buyers what one talks about and what the other treats, as if he were their encyclopedia?!”

His behavior, his sweet and humorous words, and the explanation he gave for the content of every book made anyone who entered his shop feel awkward leaving without taking at least one book. It had happened to me in another city that I saw a dusty copy of Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” on a shelf. The saleswoman, a young bride who apparently had only seen the title “Leaves of Grass,” told me:

-“It’s about agriculture!” (Which, as is well known back then, was “everyone’s business”)?

One day, when I was in Gjirokastra and went to Alizoti’s bookstore, I wanted to provoke him and said:

-“Is this book about agriculture?”

-“That is poetry written by the great poet, Whitman, and it has been translated into our language by the son of the patriot Petro Nini Luarasi, Professor Skënder.”

Once I entered the bookstore and asked him if copies of “Hosteni” magazine were left unsold.

-“They snatch ‘Hosteni’ before it even arrives, especially when there are writings about our city and district!” – he told me, and he mentioned several of the articles published in the magazine.

-“They’ve beautifully ‘embroidered’ agriculture and trade, which instead of fresh vegetables, produce and trade banal self-criticism! They also neatly ‘tailored the suits’ for two Andres and a Perlat from our city, who look for work while hoping there is no work. Or the teams that come to us from above, in and out, a Spiro, a Vangjel.” I can’t forget “The Three-Story House,” which the “Atelier” has adapted for the residents according to their color and position.

I was amazed at how he remembered so many articles published in the magazine.

Once I told him that I knew many Gjirokastrians in Tirana, and he replied that only he and Çeço (Çerçiz Topulli) were left in Gjirokastra of the old locals; the others had all fled to Tirana. Then he continued:

-“Have you seen Çeço’s monument with the cartridge belt and without a rifle?”

And with humor, he told me that during the time of the Monarchy, the Municipality of Gjirokastra decided to erect a monument to the prominent warrior, Çerçiz Topulli. They reached an agreement with the sculptor Odhise Paskali and settled the price at 800 gold Napoleons. The commission collected the money from the people, but some of it “grew legs.” From 800, only 600 remained.

-“I can’t do it for this much money,” the sculptor told them. “Look at his photograph when he was a guerrilla in the mountains. He has a cloak (guna) on his arm, which has folds and wrinkles. All of these require expenses when cast in bronze.”

-“What does Çeço need a cloak for!” – one of the commission members jumped in. “It’s not like he’s going to roam the mountains to protect himself from rain, hail, and snow. Now he is near the ‘government’ (hyqymet) and if it starts to rain or snow, let him step into the municipal offices or the surrounding shops so he doesn’t get wet. Therefore, let’s remove the cloak as unnecessary weight!…”

-“Let’s remove it!” – said the second.

-“It’s decided!” – stamped the third.

The cloak was removed, but they still couldn’t reach an agreement with the sculptor.

-“In the photo you gave me,” he told them, “Çerçiz has a Martini rifle in his right hand, and it has a barrel, a cleaning rod, a stock, a trigger, and a strap to hang it on his shoulder. All of these require not only work but also expenses, as the casting of the monument in bronze will be done in Italy!”

-“But what does Çeço need a rifle for now?!”- the other commission member jumped in. “Is he going to go fight at the ‘Plane tree in Mashkullorë’ or shoot the despot at ‘Cap’s Rock’? If a ‘muarrebe’ (war, God forbid) breaks out, there are the government gendarmes with rifles on their shoulders and pistols in their belts to restrain the troublemakers!”

It was decided to take away the rifle too, which he had never taken off his shoulder while he was alive. But another problem arose. What to do with the outstretched hand that held the butt of the rifle?

-“Problem solved!” – the commission exclaimed. “Haven’t you noticed Gjirokastrians when they climb up from ‘Qafa e Pazarit’? They keep their hand clenched in a fist behind their back.”

After telling this story about Çerçiz’s monument, Alizoti leaned in and whispered in my ear:

-“If they can ever open Çerçiz’s fist clenched behind his back, that’s where the Napoleons stolen by the wicked ones are ‘hidden’! The dissatisfaction of the people of Gjirokastra toward this unworthy event for the city was immortalized in the expression passed down through generations: ‘What is hidden in Çeço’s fist’?”

When he found out I was one of the editors of “Hosteni” magazine, he complained that we sent too few magazines to Gjirokastra, so few they didn’t even “touch the ground.”

-“Save some paper and send us three or four times more!”

Alizot Emiri was right because, in all the bookstores of large and small towns I had seen, in none of them were so many – not just magazines, but also books – sold.

A long time has passed since then. Alizot Emiri has passed away, but I can say with conviction that I have neither seen nor will I ever see a bookseller work with as much dedication as he did! / Memorie.al

Tirana, January 30, 2011

To be continued in the next issue