– Lekë Frroku: I still suffer the nightmares of the prison time, I am in a dream; o in Spaç, o in Ballsh, o in Qafë – Bari-

Memorie.al / “It’s been 28 years since I got out of prison and you know what happens to me? During the day I am free, but at night I am still in prison, because I suffer from the nightmares of the prison time. And not two consecutive nights pass without such a dream appearing to me: when I go to the technical office, I even ask how many more years of prison I have left. Sometimes they tell me four more years and sometimes they tell me two more years…”! The faces of Kristo Vangjeli, Rrapo Dhimo, Maringlen Rrapit, Thoma Janos, Mark Pëllumbi and Zef Deda, will remain forever in the mind of Lekë Frroku. It is the characters that have done him a lot of harm in his life. They did him so bad that even today, after about 50 years; he would rather be shot than fall into their hands once more.

On September 4, 1976, Lekë Froku saw himself with his hands in handcuffs. He was only 23 years old. A few moments after the arrest, in the Internal Branch of Kruja, the investigator broke his hand. A few hours later, from the torture and beatings with strong tools, he broke two ribs and finally, re-broke his hand that he had broken a few hours before. He was accused of “preparation for escape”, but also of following Italian music.

Leka was received by the investigator, Kristo Vangjeli, investigator of the Ministry of the Interior; Rrapo Dhimo, investigator of the Ministry of the Interior, Maringlen Rrapi, Thoma Jano, of the investigation of Kruja. “When they arrested me, the first thing they did in the interrogator is to break my hand with German irons. As you can see (points to hand), and to this day, I’m not okay with it. Then, stepping on me, the policeman broke two of my ribs. But breaking his arm and ribs was nothing compared to breaking them again. That is, when he knew you had them broken, the investigator should break them a second time. Yes, even for the third.

The broken hand, from Thursday, was not occupied by irons; then he would take them apart completely and then insert them from above. This was death. If they told me today: ‘Accept everything we say, and you will be shot’, or ‘Accept the torture, but don’t accept the accusations’, I would have automatically said: ‘I accept everything and shoot me’. Because I can’t bear those tortures anymore. They endure when you’re young, apparently, so much so that even I’m surprised today,” Leka confesses, in an interview for “Voices of Memory”.

The trial of Lekë Frroku had lasted three days, and then he was sentenced to 17 years in prison, on the charge of escape and that of foreign performances. After the trial, he was sent to Spači prison. After nearly 5 years in Spaç, Leka was transferred to the prison of Ballshi, to return to the prison of Qafë Bari, in 1982.

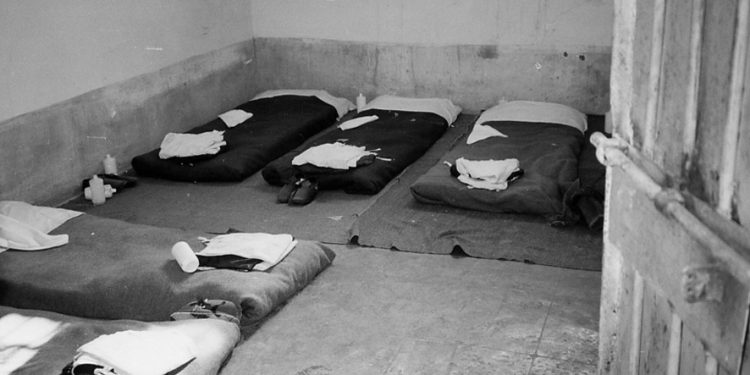

“In Qafë Bari, I experienced the most terrifying experiences. They put us on the bus; we didn’t know where they were taking us. We arrived at Qafe Bari. The director of the prison, we had Edmond Caja, who later, after 1991, became a lieutenant colonel in the Ministry of the Interior. We worked like animals, but I was young at the time…! A miner had to make in the gallery, a front with bira, with hammer. If you didn’t, they would put you in the dungeon, where they would keep you for a month. Leave the blankets only from 10:00 in the evening until 5:00 in the morning.

At 5:00, they would come and take you and you would have to sit on the floor, which was 70 cm. wide and 170 long. In that dungeon, sometimes up to nine people were put at once. Stack, on top of each other like bags of cement. There was only room to lean on each other; there was no place to lie down. All day, only on cement. They were allowed only 3 cigarettes a day: one in the morning, one at lunch and one at dinner. Our tobacco, of course, but the command only lit it three times a day”.

The Neck-Bar Revolt

“The revolt happened on May 22, 1984. I had a guard policeman at work, whose name was Kujtim Karaj. He was tough and one of the best cops. After the revolt, the dungeon guards took him to the Puka investigation, where they had also taken the prisoners of the Qafa Bari Revolt, and from him, I learned everything that was done to the prisoners. So, it is about when they arrested Tom Ndoja, Sokol Zef Sokol, Lazër Shkêmbi, Bajram Vuthi, and all the others.

He told how Toma, who had been left without food and water for four days in a row, grabbed the bucket where the floor cloth was squeezed and drank the water. He told me that Tomas had one of his eyes taken out. Sokol Sokol had one eye and shoulder taken out. The Qafë Bar revolt had such cruel consequences.

The tortures were so severe that Tom Ndoja and Sokol Sokoli could not wait to be shot, saying: ‘Aman shoots us! Stop torturing us! Sander Sokol was kicked by the policeman in the back. It happened like this: two policemen rushed at him; one grabbed Sandri by the head and the other by the legs, and broke him in half. So, it breaks his spine. They left him dead on the spot. It is not even known where his grave is. The remains of Toma and Sokol have been found, while Sandri’s has not. This was the most terrifying event of all my years in prison.”

How did the revolt start?

“Ndue Pisha did not do the norm in the mine. The police took him and tied him up. This one, as he was, in all irons, came and entered the camp. His friends who were from Tropoja, Lekbibaj and Shkodra, surrounded him and did not let the police take him. This is the moment when the revolt started. We got the policemen and officers out and for 12 hours, we were almost free. After that, someone from the Ministry of the Interior, Agron Tafa, I believe his name, came by helicopter. He ordered that in ten minutes, those whose names are on the list should surrender; otherwise, we will open fire in the entire camp!

And to prevent this from happening, to protect others, whoever was on the list surrendered. So, unlike the Spaç revolt, this one was completely spontaneous and lasted only one day. Then Edmond Caja came to the camp and caught one of us, for example, Ramiz Memçen who was from Shkodran and my friend, and gave the order: ‘Beat’! The policemen, while beating him, asked each other what he did, why they were beating him. They didn’t even know why they were beating him. That is, in vain, to create terror.

I remember another incident from Qafë Bari: they stripped us naked in the middle and above, to check us. This work like winter, like summer, the same. And the beauty was that the policeman, even though I was naked, checked me with his hands, did you say that I had hidden something under my skin. “Hey, – I told him, I’m naked”! And the angry policeman said to me: ‘You are enemies! You put the dynamite in your body and release it against us!

I’ve been out of prison for 24 years, and you know what happens to me? During the day I am free, but at night I am still in prison, because I suffer from the nightmares of prison time. So, in a way, I’m still in prison. I am in a dream; o in Spaç, o in Ballsh, o in Qafë Bari. And not two consecutive nights pass without such a dream appearing to me: as if I go to the technical office and ask; how many years of prison do I have left? Sometimes they tell me four more years, sometimes they tell me two more years.

An uncle of my wife’s name was Dodë Gegë Bajraktari, I had him in prison. It was from Manatee. When the revolt happened in Qafe Bari, Konstandin Gjorden, the police shot him and the bullet stuck in his shoulder. Doda treated him. After the revolt, Doda was put in the dungeon, from where he treated Kostanini.

When he came out, I swear to you that those red prison pants were not removed and I was forced to cut them with scissors, along with the cotton bandages that he wore under them, because they were stuck to the flesh from the blood. They had tortured him so hard. I remember Doda who told me: “The policemen felt sorry for me, because they were sweating profusely, beating me”!

Ballsh prison…!

“There was no work in Ballsh. They gave us 600 grams of bread and a dish of water. It happened to me that I found the worm in the spinach, boiled in it, and when it fell on my plate, I separated the worm separately, and ate the spinach. But in Ballsh, there were dozens of prisoners who died of hunger. If you didn’t have help from home, you were done.

A cousin of mine, Nikollë Zefgjoni, in prison, used to say: ‘I don’t want anything else from God, only to be taken out and eat alfalfa and fill my stomach’! So great was the hunger. When I went to Ballsh, I found Nikola there. I was not used to hunger, but there I realized that hunger is divided into three stages: hunger, hunger, and greed. I had bought plenty of food from Spaçi and I said to Nikola: ‘O Nikola, we are boiling half a kilo of pasta’! “What did you do to me?! Put it in my ear? They don’t work for me’, – said Nikola.

“But we’re boiling a kilo then,” I told him. “They don’t work for me,” he said. Finally, boil two pounds of pasta, with one liter of olive oil, in an eight-pound pot. I ate maybe two garuzhda, and he ate the rest. I swear I didn’t leave more than three fingers of pasta in the bottom of the pot. Even when we returned from the appeal, I saw him go back to the pot. After a few days, when he was full, he could not eat more than one or two garuzhda”.

Persecution of the family

“My father died in 1985, when I was in prison. Only 13 people went to the funeral. Father had made the grave himself, two years before he died; knew that I would not be released as long as he lived. And when he died, they went to order the coffin, and the chairman of the cooperative answered: ‘We will go and cut the poplar, we will saw it, and we will let it dry’.

So a job that took seven or eight days. In short, they didn’t even give him a coffin. The second: the State Security recorded the name of everyone who dared to come to the mortuary. People were afraid, so only 13 people went to my father’s funeral. Ten years ago, at my mother’s funeral, 500 people came.

400 people in prison for Celentano

“Part of the accusation against me was because I had listened to Čelentano! There are 400 people who were sentenced to prison at that time, just because they had heard Celentano in Albania. After 1990, they even created an association; “Friends of Celentano”. There were times when we could see some Italian station on the TV in the culture room.

Once the police caught us, seeing Celentano, Morandi and others, put us in the dungeon. “Let’s go on a hunger strike”, – I said to Sheriff Merdan, because if you were in the dungeon and had announced a hunger strike, they wouldn’t beat you, because the command notified the Ministry of the Interior in writing that; ‘so and so are on hunger strike’. So, no one beat us.

When the policeman came to bring the food, I told him: ‘I am on hunger strike’! But the Sheriff did not agree; he wanted to eat. I tried once more and told him: ‘Announce the strike, because they will beat you’! He did not change his mind. OK. He ate breakfast and was never touched. The same goes for lunch. But at dinner, they came and beat him as hard as they could. They beat him with stove wood.

And if you look carefully at the Sheriff today, there are three fractures in the frontal bone, on three different sides. These marks are exactly from this beating I am telling you about. Then they took him and took him to the infirmary and did not return him to the dungeon, but the fractures remained. So heavy that the Sheriff said: ‘Even when I’m released, I won’t listen to those songs again’!

The meeting after 30 years, with the cruel policeman

“Nikolle Uka, it was the policeman who grabbed Sandër Sokol’s back. Plus he beat the others too. About Nikollë Uka, I had heard that there was a nice club in Dardë i Puka. It was 1996, when I went to his club, accompanied by two other people. After we talked and I told these two companions who the owner of the bar was, they said to me: Can you tell him face to face, face to face?

“Yes” – I said. The club was big, two stories. We went inside. Fortunately, at that moment, a bus from Shkodra stopped and the passengers stopped to drink some coffee or something in the bar. When he brought us the beers, Nikola saw me and jumped: Lekë, we are friends, lovers…’!

“When did you become my friend”?! Nexhmije Hoxha gave birth to you,’ – I told him. Meanwhile, all the bus passengers were listening to me. To tell you the truth, I was also afraid that he, one of his friends, might come and take my head off with a crowbar.

‘You have snapped Sander Sokol on the back. You took his life. You beat hundreds of prisoners. You must be killed; you don’t deserve to live’ – I told him then. He didn’t speak. He wanted to offer us beer, but I refused in any way and got up and left. Memorie.al

The interview was taken from the cycle “Voices of Memory”, with authors Luljeta Lleshanaku and Agron Tufa