Dashnor Kaloçi

The first part

Memorie.al publishes the unknown story of Beqir Sure Ajaz, originally from the village of Prezë in Tirana, who during the period of the Bird Monarchy was educated at the French Lyceum of Korça, where he had the opportunity to meet and befriend Enver Hoxha who was an external lecturer and to supplement his salary, he also worked in the school library, where Beqiri was assigned as its guardian. How Beqiri became involved in politics during the War period (1939-1944), first joining the nationalist organization of the National Front and then the Legality Movement, being a participant in its first Congress held in the Herr Village of Tirana, on November 21, ’43, where he also served as secretary. Ajazi’s engagement with the forces of Major Abaz Kupi, where he had the opportunity to meet the British officer, Julian Emëri, (who was on a mission near the headquarters of Legality, headed by Kupi), which caused him to was arrested by partisan forces in October 1944, before the end of the war, while he was sending a letter to Prime Minister Ibrahim Biçaku, which Abaz Kupi had given him. Ajazi’s sentence was initially sentenced to death, accused of “war crimes” and then, with 15 years in prison, on the charge of “participating in collaborationist organizations”, from which he suffered 10 years, after benefiting from the amnesty of 1949, when the minister of of Internal Affairs, Koci Xoxe. The unknown history of Beqir Ajaz, from the period of the War and until the collapse of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, where after he rejected the “offer” of the State Security, “to escape from Albania” and to go on a secret mission to England, where he would get in touch with Minister Julian Emeri, (with whom he had known since the War period, when he was in Abaz Kupi’s Staff), as a sign of revenge, in 1986, the Security of The state arrested his son, Namik, sentencing him to 10 years of political imprisonment, which he served in the Qafë Bari and Burrel camps, from where he was released only at the beginning of 1991, with the collapse of the communist regime. How did Beqiri manage to publish after the 90s, several books with memories such as: “From Shkaba m the crown at Drapri with a hammer”, “I didn’t share the prison of Burrel”, “Sure Ajazi, this kreshnik of our time”, “Who was Enver Hoxha”, etc., as well as books with translations, (mainly from French) , such as: “Tistan and Izolta”, “Henerieta”, “Ethnic cleansing”, “Unholy war”, etc.

Who was Beqir Ajazi?

Beqir Ajazi was born in 1920 in Dibër te Madhe, where his family was at that time, but their origin is from the village of Prezë in Tirana. His father, Sure Ajazi, was the governor of Preza and during the years 1915-1920, like many well-known families of central Albania, he was one of the supporters of Esat Pash Toptan. In the years of the Bird Monarchy, he suffered several years in the prison of Gjirokastra, after being convicted for a murder he committed for blood feud. Also for this reason, the family sent Beqiri to continue his studies near the boarding school of the unique school in the town of Erseka in the district of Kolonja.

After finishing it with high results, in 1933, Beqiri won the right to attend the French Lyceum of Korça, where he had the opportunity to meet Enver Hoxha, who in 1937 was assigned as an external lecturer at that school. In 1937, after Enver Hoxha could not complete the full hours, in order to compensate the salary, he was assigned to work near the school library, where Beqiri was the responsible custodian, with whom he worked for three years in a row. In 1939, when Fascist Italy undertook military aggression by attacking Albania, Beqiri joined the volunteer battalion commanded by former Liceu professor Abaz Ermenji.

After the closing of the High School by the Italians in 1940, Beqiri returned to Tirana, where he enrolled in the state high school, which he finished in 1942, graduating with high marks. During the time that Beqiri was in Tirana, he often met with his former teacher Enver Hoxha, who had started working selling cigarettes in the store “Flora”, owned by the family of Ibrahim Biçak, (Esat Dêshnica’s uncle), with him whom Enveri had known since he was in the city of Korça.

In that period of time, Beqiri also worked as a journalist in “Bashkimi i Kombit” and in 1942, with the encouragement of his former teacher, Abaz Ermenji, he joined and joined the political organization “Balli Kombëtar”. Whereas his father Sure Ajazi, for his anti-fascist activity, after refusing the rank of colonel offered to him by Mustafa Kruja, was exiled to Italy from 1940 to 1944.

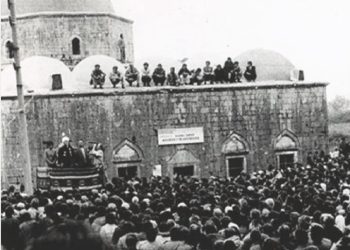

In 1942 Beqiri left the forces of the National Front and joined the forces of Legality led by Abaz Kupi and participated in the Congress that was held in the Herr Village of Tirana on November 21, 1943, where he also served as secretary together with Nevzat Vila. In 1943, Beqiri was appointed to work as a secretary in the Ministry of Popular Culture and then as an editor in the Albanian Telegraphic Agency.

Due to the fact that Beqiri knew several foreign languages well, such as: English, French and Italian, in 1943 with the arrival of the British missions near Abaz Kupi’s headquarters, he was assigned as a translator and liaison officer between Kupi and the British officers where he stayed until the fall of ’44 when Abaz Kupi left Albania.

During this time, Beqiri developed a close friendship with British Major Xhulian Emëri, whom he kept for three weeks at his house in the village of Prezë when he was wounded. On October 14, 1944, while Beqiri was returning from Tirana, where he had taken a letter to Prime Minister Ibrahim Biçaku (which was sent by Abaz Kupi) on the way to Preza, he was arrested by the partisan forces, who kept him isolated in some improvised barracks as a prison somewhere on Dajti mountain and on November 21, after the departure of the Germans from Tirana, Beqir and the other prisoners were brought to the old prison of Tirana.

On April 25, 1945, Beqiri appeared in court and was initially sentenced to death, being accused of “war crimes”, but then the article was changed and he was sentenced to 15 years in political prison, accused of: “participating in collaborationist organizations”, seizing all the properties and assets that the Ajazi family had, mainly in Prez and Tirana. Sometime later, on June 7 of that year, the communists shot Sura Ajazi’s father, who had previously been arrested as an accomplice of Abaz Kup. Likewise, after a year, on August 3, 1945, in a gun battle with the forces of the Defense Division in the surroundings of Tropoja, Sulejmani, Beqir’s brother, was also killed.

Of the sentence of 15 years, Beqiri suffered only seven years, because he benefited from the pardon (amnesty) that was made in ’49, after the hit of the Minister of Internal Affairs, Koci Xoxe, whom Enver Hoxha, apart from the accusations of others, he charged all the crimes that had been committed up to that time. Beqiri was released from prison on June 17, 1954 and worked as a manual worker. But even after his release from prison, Beqiri was under the strict surveillance of the State Security, as was usually the case with all former political prisoners and their families.

In this regard, Beqiri testified to us: “In 1975, the State Security called me allegedly for an explanation and after they told me some general words, as I was used to them, such as: The party had the heart of big and was also thinking about the rehabilitation of former political convicts’, entered directly into the topic, proposing me to cooperate with them. They even told me that they had a concrete plan that I would allegedly escape from Albania and go to England, next to Julian Emri, (a former British officer who had been on a mission in Albania during the war), who at that time was a minister in the Conservative government.

But I very tactfully and categorically rejected the “offer” of the State Security, telling them that I had no possibility to realize and afford such a thing. But even though they insisted that I would have their unsparing help in carrying out that mission and that that patriotic duty was done for the high interests of the country, I was determined, saying that I could not accomplish that thing. But even after my refusal, they told me to think for a few days and they would call me again, but I persisted, saying that I had nothing to think about, since for me it was an impossible mission.

Only after that, after seeing my determination that I was categorically not accepting the cooperation they were offering me, they lost hope and asked me to sign a statement, where I wrote that I would not even tell the man regarding that meeting and what we had talked about there, on the contrary, I would have been arrested immediately and jail was waiting for me, for “high treason against the motherland”. I of course signed the statement, writing that I would not tell anyone about that meeting and that everything was discussed there, (which I really followed through on, not telling anyone about it, at least until 1989-90, when I you could see that that regime had its days numbered), but after three days, on October 14, 1975, I was interned as a family in Smokthina in Vlora”, recalled Ajazi, the “offer” of the State Security.

Beqiri remained in exile until August 1984, when he was allowed to return to Tirana and after four years in ’86, the State Security arrested his son, Namik, who was initially sentenced to 20 years of political imprisonment , accused “of attempted violent overthrow of popular power”, and then 7 years in prison, for “agitation and propaganda”. Namiku served his sentence in the camp of Qafë-Bar, and Burrel, from where he was released only at the beginning of 1991, with the overthrow of the communist regime.

After the 90s, among other things, Beqir Ajazi devoted himself to his first passion, journalism, publishing various articles in the newspapers and magazines of the time, which he continued with great passion even though he was in a broken age. In addition to his writings, he also wrote several books (mainly memoirs), and managed to publish the book “From the Crowned Vulture to the Hammered Sickle”, which was well received by readers, researchers and historians, since in that book he deals with professional competence and historical authenticity, different events from his life and others that he had learned from different personalities and people whom he had known mainly in the prisons of the communist regime.

Similarly, after the first book, Beqir Ajazi published several other books, such as: “Burgu i Burrel”, “Sure Ajazi, this kreshnik of our time”, “Who was Enver Hoxha”, etc. In addition to these books, Beqiri was also involved in translations (mainly from French), translating the books “Tistani and Isolta”. “Henerieta”, “Ethnic cleansing”, “Unholy war”, etc.

Beqir Ajazi passed away on August 3, 2017, at the age of 97, and was escorted to his final residence with many honors by the Associations of Former Political Prisoners and Persecuted of Albania and by his fellow sufferers. In 2002, the French state decorated Beqir Ajazi with the high title “Knight of the Order of Merit”!

Memoirs of Beqir Sura Ayaz

“How did the partisans arrest and imprison me since October 1944”?

The day of November 21, 1944, was and remains for me a strange coincidence. It makes me go into deep thoughts, but then I had neither mind nor life experience…!

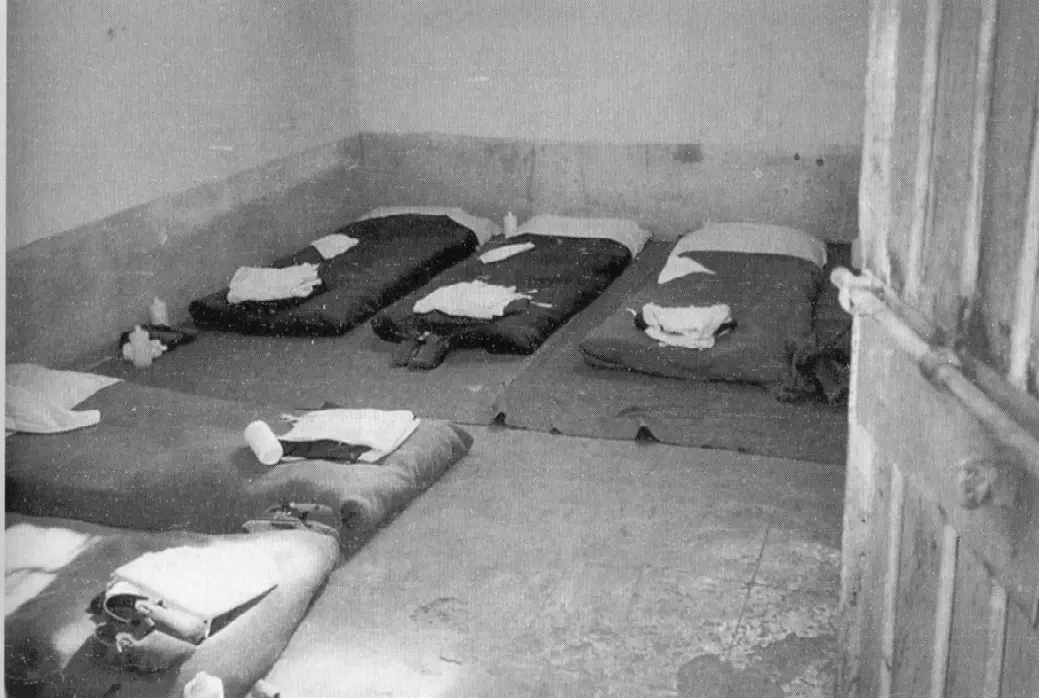

Where we were slaughtered like cattle, it was a real misery, an abandoned hell and left in an unusual condition. The ordinary prisoners had just come out of there, and the 17 German prisoners who had been there had been taken out a little while ago, slaughtered in a small cask near the bathrooms.

We, who had just arrived from Shënpali, were almost 300 people…! The number of prisoners increased from minute to minute, thanks to the zeal of spies without money, who were roaming in Tirana at that time. This category of people, whom the centrifugal force of society had thrown out of their circle because, being without any norms of humanity, they had wormed themselves into debt and among vices, went after the partisans and with the aim of creating for themselves a certain confidence in these newcomers, as if they were supposedly warriors of the inner terrain, they charged anyone.

And the partisans entered the houses of the world, slaughtered people like cattle and came and killed them in prison. Before they killed all the German prisoners in a casket, they had the whole prison at their disposal and if they could get a little warm on that bare cement, without any layer of covering, they burned whatever they could find, like cardboard and pieces of tar – tip. Thus, all the walls of the kaushas were blackened and made like the bottom of the kaushas.

A young man with artistic inclinations, who was also given to painting, with a nail that he had just found, had scratched a Skenderbe the size of the wall. Nuredin Çabej, apart from this drawing, had written in beautiful artistic writing on all the doors: “Lasciate ogni speranza, o voi che entrate” (“O you who enter here, abandon all hope”).

In this rhythm of arrivals of prisoners, since the evening of that first day, we were so packed and compressed between us, that we had no possibility to move, let alone lie down; there was no question at all. As the hours passed, the prisoners brought by the partisans became so numerous that the internal guards could no longer handle the treatment of the Germans. Therefore they opened their door and thus, Germans, women, and Albanians, became one.

Since the communist prison was not yet finding its classic form, they kept us together, men, German prisoners and women…! There were two Italian women among us, one of whom had a four-year-old son called Franco. This piciruk, sleeping with his mother in the middle of all that mess, was scared, especially when he heard the heels of shoes with thick spikes, which danced on the feet of the partisans.

The windows of the kaush, which were placed at the height of the ceiling, were not only one palm high and, just as wide; they also had three types of wires of different thickness and fineness. Zog’s prosecutor never allowed more than 13 people to live in such a kausha, and now that Enver Hoxha was taking over these kaushas, there were no less than 40 people there. In consequence of this tightness, there was not enough air, so that we were obliged to snort, as chickens and dogs do in summer.

When we saw that no one remembered that we were dying for air, the boy Skender Dine, an agile boy, bound and with the body and muscles of an athlete, climbed the wall and managed to put one knee on the window sill, from where he then, maintaining the balance of his body, with a safe hand, smashed and pulled out the three window frames and threw them on the ground, as if they were rags. From that moment our breathing became somewhat easier, and we said that we were born again, because, with no one cracking our heads for us and no one officially having us in charge, no one was responsible if we should die for due to shortness of breath.

If something like this happened in Zog’s time, the prosecutor who had put more than 13 people in jail than the law allowed, as well as the Minister of the Interior would have their rags flying and I don’t know how they would have parted with the imprisonment. So we had avoided this certain danger that was threatening us with the “sword of the dardhar”, and no one knew what we had done. It was a lot of work…”! Memorie.al

The next issue follows