From Uvil Zajmi

Part one

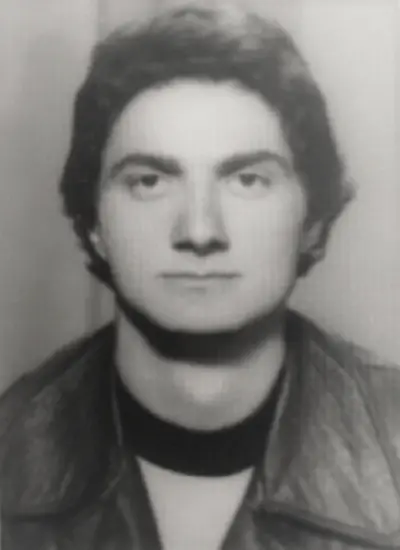

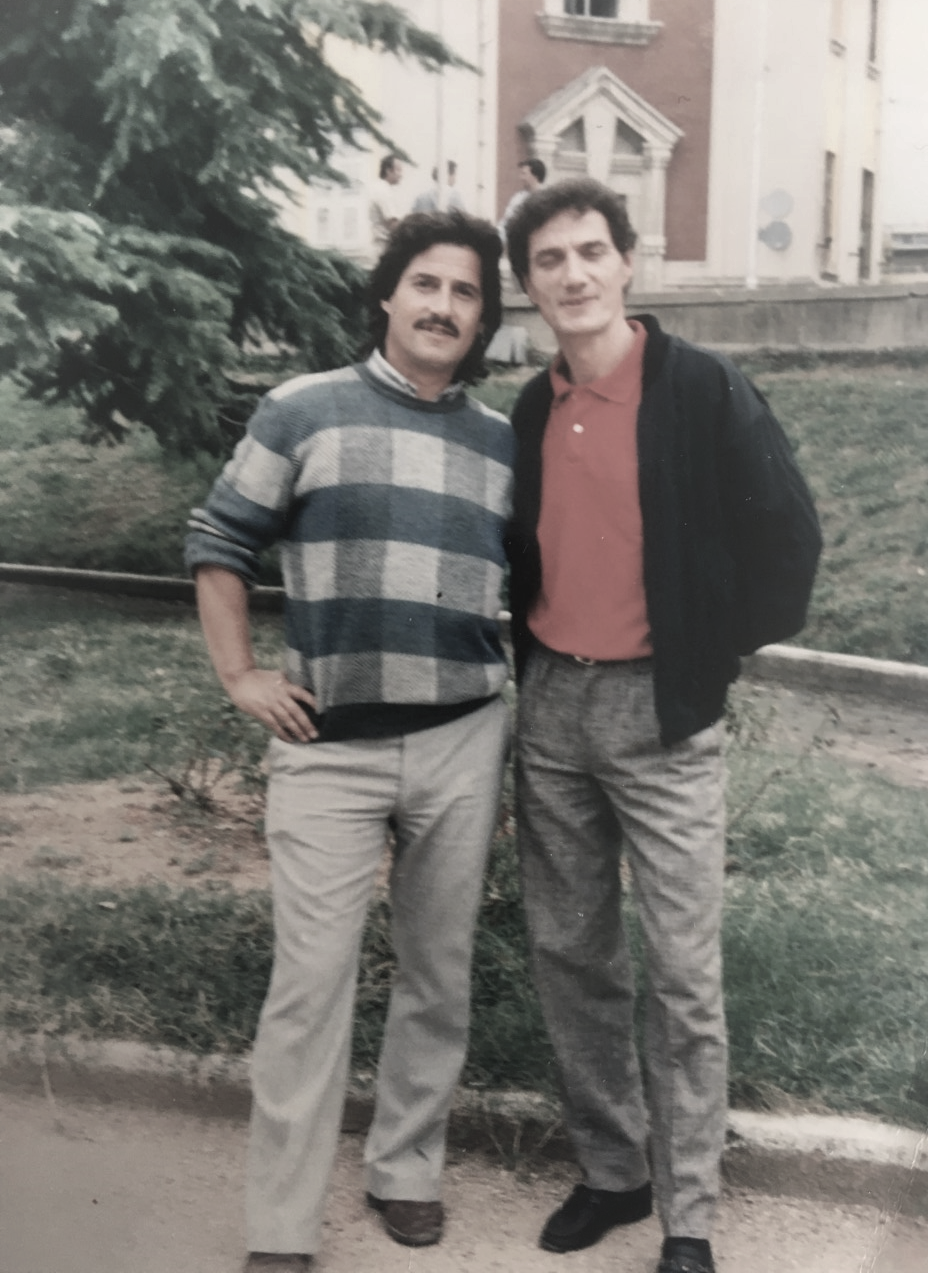

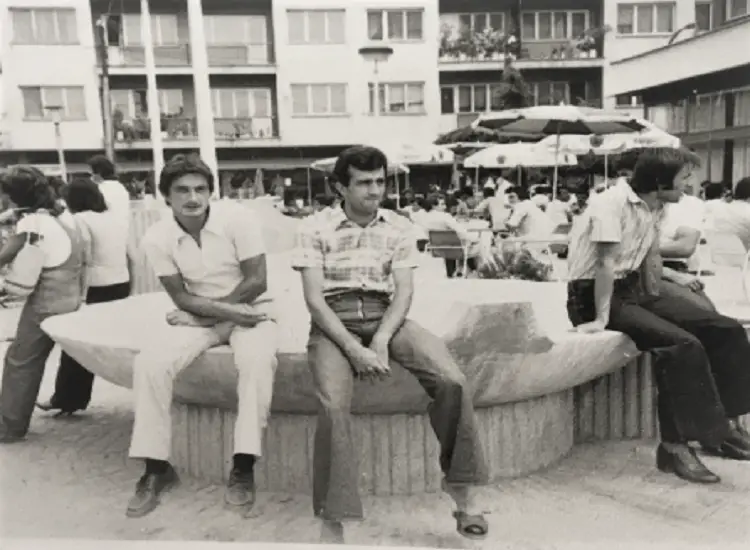

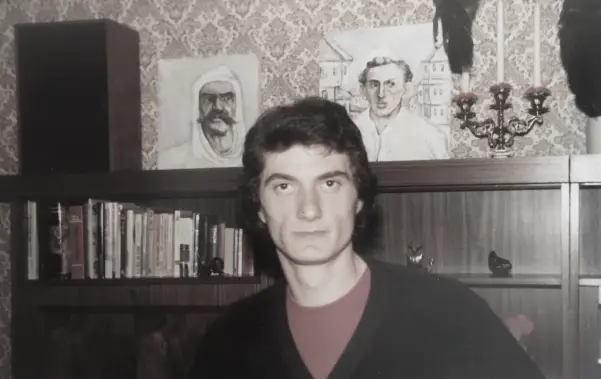

Memorie.al / The escape of Mustafa Korça were not an escape like the others. Of course, sensational like all in that period, for the challenge, the courage, the way, above all for the alarm, the blow that this event gave to the prepotent, aggressive, isolationist and dictatorial state. But Muç Korça’s was different: A 21-year-old young man, artist, painter, sculptor, and escapes by abandoning the border point, the pyramid, where he was assigned to perform military service, even together with the “Kallash” who had given to protect the border from “external and internal enemies”! The surprising news spread quickly: “Muc Korça has escaped… he has escaped.” He also left a letter.” Today, after nearly half a century, Mustafa Korça (Muçi) returns to that event, the moment he made the decision, the letter he left behind, crossing the border, dawning on December 21, 1978. “I escaped because I was denied the right to study”, he says. Mustafa recounts his stay in Yugoslavia, Italy, Belgium, life in Sweden, then in the USA. The desire to meet the players of “Partizani” in Malmo, where he also met the son of Enver Hoxha and Mehmet Shehu and their companion, Gani Kodra, with the dancers of the State Ensemble of Folk Songs and Dances in Hamburg and Gothenburg , etc. Muçi still keeps letters, postcards, documents, rare photos of the time. He has not changed; he is the calm Muç Korça, with a measured judgment and reasoning. “Some time ago I was in Resnje, Macedonia, the city where I stayed after escaping. I had never been before”, he says in this interview.

Mr. Korça, do you remember what the atmosphere was like in Albania in the 70s, that is, before your escape?

After the 70s, hopes for Europe were closed for everyone, especially for the youth and its dreams. Total isolation, the economic and political situation was aggressive, more difficult than ever. In particular, the fight against foreign shows was felt in everyday life, work, and school, everywhere.

You completed the Artistic High School, but they didn’t let you graduate, what was it like?

From 1971 to 1975, I attended the Artistic High School “Jordan Misja”, in Tirana, in the branch of sculpture. Without wanting to brag and talk about myself, for the sake of the truth I have to say that I was among the best in the class, together with Agim Mujon. A few months before graduation there was an event, I was punished for liberal behavior, foreign shows, as I was a thrown, agile, modern type. They gave me this as a pretext, even though I had prepared the study as a diploma defense, but they didn’t let me defend it.

Unparalleled selfishness by director Ruhi Pashari. A great injustice was done to me, for no reason. And the peak was when I was assigned to Mirdita, as a designer. An absurd appointment, only with high school, without obtaining a diploma, which was an illegal act. I stayed two days in Rrëshen, at the House of Culture, and returned to Tirana. I remember a manager, Gojard Daia, a good man; he helped me get the documents, which made it possible for me to start working as a set designer at the Opera Theater in Tirana.

How did it become possible to start working as a scenographer at the Opera Theater?

It was very difficult for me to start working at the Opera and Ballet Theatre, but it became possible in 1976, and the director at that time, Xhemil Simixhiu, a noble, liberal man, helped me a lot to get settled there who in many cases has protected me from the Party Secretary’s attacks. The father had worked for many years as a tailor there and in 1976, he had passed away.

I worked as a set designer together with well-known painters such as Hysen Devolli, Gjergji Marko, Niko Progri and K. Dilo. I realized the scenography of the ballet “Invincible Land”, “Carnivals of Korça”, etc. During that period, I also worked with the reliefs of the congress hall backgrounds, with polystyrene, where I became a professional.

And yet, military service was waiting for you, right?

I was 21 years old, in September 1978; I suddenly received the call-up letter to perform compulsory military service. In a flagrant way, they didn’t even give me time to complain, which was a form of shutting me up, removed from work and from Tirana. Everything happened within a few days and I was sent as a soldier to Korçë, 27 months at the border. It was a surprise neither I nor my family expected. Three months of quarantine I was bored, a big psychological shock.

I was assigned to Nikolica on the border with Greece, which was the worst area. My being sent there was like a punishment, since a bad relationship had come from Tirana for me. I reacted and before we left, a soldier, Capt. Mati, comes and says to me: “Soldier Korça, you will go to Gorica e Madhe where you will stay for only one month, then you will come as a designer in the military branch in Korça”, which which made me happy and calmed me down somehow.

Meanwhile, did you ever think you’d run away?

I had made up my mind that I was going to run away, but I had never discussed it with anyone, not even friends, not even my family. I had only talked a little with a friend, Ilir Melo, also from Tirana. Iliri was a handsome boy, with an ambassador father, he was born in Czechoslovakia.

We became friends in those months, we opened up to each other, and we had the same idea, to escape. After a week, when I escaped, they had called him from the Security and asked him: “Have you talked to Mustafa? What did you discuss; he told you that he would escape”?! He answered: “No, no, we have never discussed such a thing.”

Did you meet Iliri afterwards?

First of all, I wanted to say that with Iliri, after escaping, we had arranged to meet in Paris, one of the nights when the moon was full, futuristic meetings, age fantasy. But when we were divided into different departments, it turned out that he was not on the same page as me. So I ran away, I escaped from the village of Goricë, but he couldn’t.

Today, Iliri is in the USA and in 1996, in New York, quite by chance in a bar (Bar-Cafe), he was told about me and he asked and we met. We hugged each other longingly. “You know this man,” he told his friends who were there, “only I knew that he would escape.” There he told me what had happened after I escaped.

How do you remember when you were sent to serve in Gorica e Madhe?

They put us in a vehicle and took us to the border point, about 1 hour away from Korça, Gorica e Madhe. As young soldiers, we were escorted to see the border belt, the clone, climbing the Dry Mountain. They informed us about the conditions of the service, where and how it would be performed. There were several such: “Secret Service”, the one with movements in the border zone and “Point Service”. They gave me the gun and 300 cartridges. There were about 15 soldiers there.

How do you remember the escape?

I have it all fixed minute by minute, as if it happened yesterday. It was 4 o’clock in the morning when I received the service, it was the first service, (“Point service”, it was called), dark night, alone, horror…! Think: from Tirana, border guard…! It was December 21, 1978, around 05:00, not yet light, a bit foggy, cold…!

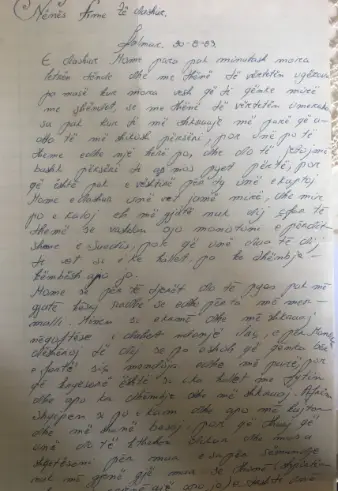

I decided to escape. I left the service, I remember the pyramid written on two pages and with the ‘cane’ in my hand, I crossed the border fence which was low, 1 meter. When they showed us the area, I fixed it by orienting myself to the Yugoslav border point, about 300 m. away. (Before I took the service that night, I left a letter there, under the blanket of my bed).

I followed a straight gravel road, it was downhill and until the asphalt started, there was no one. Stenja was the nearest village, about 1 km. So in a few moments, I had crossed the border and was in Macedonia. I was completely numb, it seemed unbelievable, even like a dream, I had cold sweats, strong emotions, but no fear.

Did you know where you were going, the village, the area, which was the closest?

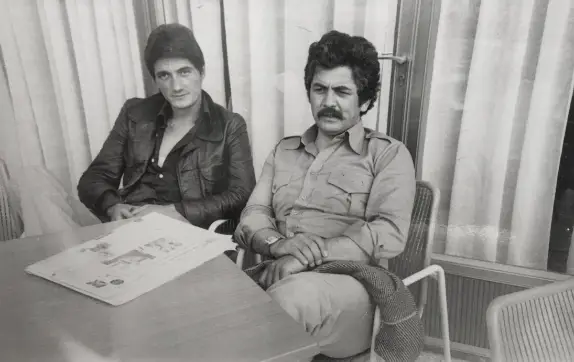

I knew nothing. In Stenje, the police station was a small house, where a policeman raised his hand to honor me, because he saw me as a soldier, “Neighbor, neighbor”, were the words he said to me. They put me in a room. After half an hour, everyone came, with the chief in charge. He had panicked. After a while, they brought me an interpreter, Bashkim Avdyli, a Kosovar, a very good guy who was doing military service there. They asked me for my gun, I refused, but Bashkimi approaches me: “Hey Albanian, hand it over and ask for asylum”, he tells me.

They understood that I had escaped, but a soldier had never escaped there before. They brought me to eat, white cheese, eggs. I spent 9 days in semi-isolation in a basement, but everyone was kind to me. On New Year’s Eve, I was invited to watch TV. Then they took me to Resnje, first to a police station, then they put me in a hotel, “Kitka”, it was called, in a room on the third floor.

What about the letter you left by your bed, what did you write and who was it addressed to?

In those two pages of letter that I wrote in the evening, before I took the service, I addressed to the state, with names and details about all the injustice that had been done to me, starting with the school, the denial of the right to study and that it what I had done was not a political escape. The latter, so that it was not an escape for political reasons, I did to save my family as much as possible.

I put it under the blanket of the bedroom and closed it with the words: “Greetings from the fugitive Muça Korça”. Later I learned that the information about what I had written had reached Tirana. In fact, the State Security had opened up that: Muç Korca has been arrested, showing as a fact my bag, the military one that I left behind when I left. But nothing was real, we were just their machinations.

When you were in Resnje, were you afraid of any reaction from the Albanian state, that is, that they might return you?

I was not afraid, but I did not rule out the possibility that anything could happen. In one day, two “TIR” transport trucks from Albania arrived in Resnje, and the drivers slept that night in the “Kitka” hotel, where I was. The people at the reception informed me by showing me their passports that they had left there (at the reception) when they registered.

I saw their faces, but I didn’t recognize them. “Don’t go out, stay in the room because you are facing them. However, you are under our surveillance, we guard you, but don’t leave because the Albanian State Security can be dangerous”, the Yugoslav authorities who had me under surveillance, who were very liberal, advised me.

Was your escape celebrated there in Resnje?

Not even the local newspaper, radio, TV, had given any news about my escape. I used to go out in the city, walk with Bashkimi. When they gave you asylum, the Yugoslavs didn’t take you back, even more so for a runaway soldier. Immigrant law protected me. They sent me to a store where they bought me clothes and offered me to start working as a designer in Resnje, at the well-known firm “Agrofllot”, but I refused.

How long did you stay in Resnje?

I stayed there for two months. They provided me with food, a pack of cigarettes a day and 20 thousand dinars. I was questioned only two or three times, with the usual ones: “What prompted you, why did you run away, etc.”. I spoke quite calmly, explaining the purpose of my escape. I did not ask to appear on TV: as I told you, I wanted to escape as much as possible, or rather not to burden my family in Tirana any more.

Based on this, I told them that: I escaped only to continue my studies, I am an artist, I want my private life, etc., things of this nature, without a political background. I have not accepted every offer they made me, certainly not under coercion, nor psychological or physical pressure. They saw me young, they didn’t suspect anything.

What happened next?

From Resnja they took me to Skopje, where I stayed for 1 month in a gymnasium dormitory. They gave me a “Lična carta za stranac”, a document for foreigners. Walking in Skopje, in a clothing store, I meet a person by chance. I remembered that in Resnje he had been brought as a special officer to interrogate me.

As soon as he saw me, he recognized me, he asked me in Albanian: “Muç, what are you doing, how are you, how do you feel”? I was surprised and asked him: does he speak Albanian, because in Resnje it had not appeared to me that he knew Albanian. “I am a Serb from Kosovo”, he told me and showed me that he had studied the Albanian language. “I feel sorry for you, don’t go to America, it eats you, stay, stay close to Europe”, he advised me very kindly.

When did you leave Yugoslavia?

I stayed two months in Skopje, while at the beginning; I had wanted to leave Yugoslavia. In no time the approval came to me. They took me to Belgrade, to a political asylum camp, where I found two other Albanians. I only stayed a few days there, and then they put us in a car and sent us to Sezhama, a village on the border with Italy, near Trieste.

They left us there and told us to cross the border at night. During my stay in Yugoslavia as an asylum seeker, I was given a notification letter, but as I was going to cross to Italy, it was taken away. It could have been April.

While you “cracked the thorn”, how did the family experience your escape, what happened to it?

We were 5 children, 3 boys and two girls; we lived in “Kavaja Street”. I was the fourth. I was an outgoing guy, but not a loud one, quiet in general. I was informed about what had happened to my family after a few years. Even they were surprised when they were told and then had serious consequences.

The older brother, who was a soldier, had been demobilized and taken to work as a factory worker “Dynamo”; sister Monda, they did not give her the right to study, and even separated her husband, as “with a bad biography”, since he had a communist brother.

The other brother, Afrimi, was removed from the State Ensemble and sent to the “Josif Pashko” Construction Plant; the other sister, who was a teacher in the village of Kallmet in Lezha, was fired and left without a job for ten years. Without any support, no one spoke to him, not even uncles, aunts, relatives, did not come to the house. As the neighborhood watched over them, it constantly guarded them. Memorie.al