By Njazi Nelaj & Petrit Bebeçi

Part One

Fate, which morning, was not with the commissar!

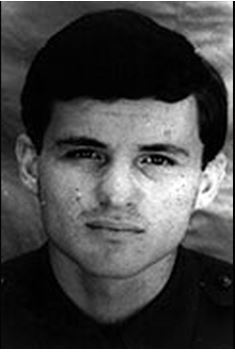

Memorie.al / Luto Refat Sadikaj enter the ranks of the “elite” Albanian aviation pilots of all time. He was one of the pilots of the first group prepared, from the very beginning, at our aviation school in Vlorë. Thus, Luto Sadikaj is a “domestic product,” one hundred percent. Not only that. Luto Sadikaj was “kneaded” and perfected up to the sophisticated aircraft of the time, the MiG-21, on Albanian airfields, with local instructors, according to the combat preparation course and Albanian aviation regulations, under conditions where limits were constantly decreasing and without having two-seater aircraft. We are perhaps dealing with a unique case in the world history of combat aviation.

Luto was born in the village of Çorrush, Mallakastër, on February 1, 1944. When Luto was born, it was the marrow of winter and the country was under the brutal occupation of the German Nazis. The village of Çorrush, as a nest of the struggle for freedom, had suffered considerable damage and destruction from the invaders’ retaliation. The family of Seit Sadikaj, a fighter of the Albanian bands that fought in Vlorë in 1920, like many other families, had experienced pressure and terror because four of its sons were partisans.

Luto’s family of origin belonged to the poor stratum of the peasants of Çorrush and Mallakastër. They managed with what little goods and stock they had (sheep, goats, and a cow) which had escaped the greed of the foreign invaders and their collaborators during that devastating operation against that patriotic region. While being rocked in the wooden cradle, Uncle Refat’s infant son, alongside the lullabies sung by Mother Bejlere – which had combatant tones and emphasis – also heard the gunshots that disturbed his sleep. He grew up and became a man, a true “lion” (asllan), just like the name of the neighborhood where he spent his early childhood. As soon as he stood on his feet, from his first steps, chubby Luto stood out as a healthy, handsome, powerful, loving, polite, and kind-hearted boy.

Luto Sadikaj spent his childhood until the age of 5 in his birthplace, Çorrush. The soil where he grew up was deeply patriotic and freedom-loving. The houses and huts of the poor peasants had turned into “fortresses” of the struggle for freedom. The residents had adopted the slogan of the National Liberation War: “Death to Fascism; Freedom to the People.” This environment raised Uncle Refat’s second son, not with pampered indulgence, but amidst the difficulties of the time. Little Luto, clinging to the corner of Mother Bejlere’s sateen skirt, would wait for and see off the small livestock and the family’s only cow, with whose milk the family was fed.

Luto was tempered by the fresh wind of the “Bregu” of the “Asllane” neighborhood and the entire ridge that led from Maja e Dokes, Çaushajt, Hadërajt, Asllanajt, Varfajt, and Shullëjasit, which blew from the side and rose upward as if it wanted to tear off the roof boards and the bundles of straw with which the roofs of the dwellings and animal huts were woven. The pastures where the Asllanaj livestock grazed were on both sides of the ridge, especially on the Eastern side, where Margëlliçi is located, where the Sadikaj fields were. Even friendships and marriage alliances were made by the Asllanaj and Sadikaj families with the peasants of neighboring Kalivaç, with whom they “tuned their strings.”

The house with a basement of Seit Sadikaj, on the upper floor, turned every night into a hive buzzing like a beehive, where partisans from Çorrush and surrounding villages entered, exited, and were supplied with food and ammunition, and where patriotic words boiled. With love for those lands and respect for the elders of the family and clan, the chubby son of the Sadikajs was nurtured from childhood; he inherited prominent patriotic virtues from his ancestors and formed a well-developed physical frame and human feelings of benevolence.

Luto was the second son of the family, after his older brother, Sadiku. After him were born: Uljanova; Sofia; Agroni; Tatjana; and the youngest, Astriti. After the end of the National Liberation War and the liberation of the country, on the eve of the 1950s, Uncle Refat’s family with seven children settled in Tirana. They were established in a simple dwelling on “Kavaja” Street. These were difficult years after the destruction brought by the war, and the family faced the hardships of life in the capital with difficulty. The year 1951 took Uncle Refat and his family to Burrel.

A different environment, other traditions and customs; economic difficulties and the tightness of the family increased. The family, now with more members, faced life’s hardships with Uncle Refat’s salary as an officer and the housekeeping of Mother Bejlere, who was a woman and mother deeply dedicated to her children, her family, and her husband. In Burrel, Luto Sadikaj completed his primary school and part of his seven-year school. In every class, he was distinguished, and at the end of the year, the directorate rewarded him with a certificate of praise. He watched his parents toiling at work to make ends meet, and Luto, still not fully grown, being the second son and a kind-hearted soul, felt the responsibility to contribute however he could to lighten his parents’ burden.

As his brother Sadiku told me: “still not grown, based on his developed physique which burgeoned every day, Luto Sadikaj voluntarily took on the duty of the family woodcutter. He found and organized all the work tools a woodcutter needs to perform his duties. In our house, you could find iron sledgehammers, axes, saws, metal wedges, etc., for splitting firewood. Every day, he split about one cubic meter of wood and would not let us take a single piece. He aimed to split the entire stack of oak wood that our family had. He also kept his work tools constantly cleaned and oiled, ready for work. Just like the wood, Luto did not even allow us to touch the work tools with our hands!”

In 1957, when Refat Sadikaj’s family transferred from Burrel to Tirana, Luto was 13 years old. He completed two years of the seven-year school, and in 1959, a qualitative change occurred in his life. In the autumn of that year, the boy with the developed and compact body entered the “Skënderbej” military high school in Tirana. They don’t say for nothing: “where it has flowed, it will drip!” Uncle Refat’s second son was to become an officer. That family of patriotic fighters could not be imagined without a defender of these lands, with military schooling and culture. The seasoned fighter Refat Seit Sadikaj had a project in his head to ensure the continuation of his family and clan tradition.

The plan that had taken place in his head was kept secret; only Bejlere knew it. One of the sons, Sadiku, he would make a pilot. Those situations came to the former partisan’s mind when he and his comrades pointed their old rifles against fascist airplanes, which circulated freely over partisan positions and left for their bases unpunished. Sadiku was the eldest son of the family, or, as it is commonly said in Çorrush and the surroundings, he was the “first bread.” He was sent to the Soviet aviation school to learn the theory and practice of flights.

Unfortunately, one day, when Sadiku and his group comrades had gone out to the start (airfield) to fly, an airplane that deviated from its landing direction struck Sadiku in the leg and injured him to such an extent that he was declared unfit to become a pilot and transitioned to another profile, closely linked to flight. Officer Refat Sadikaj’s plan “failed,” but he did not surrender to fate; he had thought of a reserve variant. But he had to wait and be patient until the second son, Luto, grew up, who had good attributes to become a pilot.

In August 1959, Uncle Refat’s second son, Luto Sadikaj, sat at the desks of the “Skënderbej” military high school in Tirana. The seasoned partisan’s heart swelled and his eyes brightened when he saw his son dressed in the beautiful uniform of a Skënderbegas and the cap with a red star on the forehead. He impatiently waited to see his son over an airplane. An internal voice whispered to him: “Be patient, man, for your dream has not been extinguished. Wait until Luto grows and becomes a man, and you will have the pilot in the family!” This is what Uncle Refat thought, hoping that one day he would see his son in the air, mounted on the duralumin horse, master of Albania’s heavenly spaces. And he was not disappointed. This is how Petrit Bebeçi, Luto’s close friend from the “Skënderbej” school until Luto fell heroically in the line of duty, recounts the event:

“I met Luto on August 15, 1959, in Tirana. That year, 350 students were expected to come to the ‘Skënderbej’ military high school. From the city of Tirana, there were 10 of us. We all came from military families who had participated in the National Liberation War, partisans. The first day of reporting to school was very exhausting. The ten of us had to prepare the dormitories for 350 students. We were 13-14 years old. We looked carefully at each other, dressed in the beautiful uniform of the ‘Skënderbegas,’ and the friend in front of us, surprisingly, seemed smaller than ourselves. On September 1 of that year, we started the first day of school. We were a year older and had entered the gymnasium. This made us happy and we felt pampered. We had to familiarize ourselves with communal life and the barracks regime.

We were in a military school where every action was performed with order and on schedule. The daily regime was: 6 hours of lessons in class. At 2:00 PM, we ate lunch. After lunch, we had 2 hours of free time. From 4:00 PM to 8:00 PM, we did mandatory study to prepare for the next day’s lessons. At 9:00 PM, we went to bed. This was also mandatory, as the next day we would wake up at 05:30 AM and were obliged to leave the dormitory within 3 minutes. Until we made this action our own and performed it according to requirements, the supervisor would send us back several times in a row. Within the school territory, all movements had to be done with a marching step and song. We were still not fully grown, and this lifestyle regime exhausted and bored us. We thought, more than once, of abandoning the school, but we backed away from the decision for the sake of personal pride and the respect we had for our parents.

I became closer to Luto and our friendship strengthened when he started playing football and I was part of the school’s gymnastics team. Luto Sadikaj quickly became a member of the ‘Partizani’ youth football team. From the beginning, his rare will caught my eye. In the evening, when we were getting ready to sleep, Luto would perform 100 squats on each leg. This action strengthened his leg muscles and increased the striking force of the football. At midday, during ‘free’ time, Luto Sadikaj exercised on gymnastics equipment. Thus, he formed a body full of muscle, strong and agile, and became the potent left attacker of the ‘Partizani’ youth football team, with a fantastic strike of the ball.

With lessons and sports, we passed the four years of the ‘Skënderbej’ school reasonably well, which at that time was among the most renowned gymnasiums in the country. The school served to increase our abilities as quality athletes and equipped us with knowledge in several fields. Besides general subjects, we learned world literature, psychology, astronomy, were introduced to skills regarding automobiling, wood and metal work, and tempered our physiques through military preparation. Our teachers were among the most prepared and competent in the country. The ‘filters’ in every class were strong; those who deserved it passed. Suffice it to mention that out of 350 students who started lessons in the first year, 170 ‘Skënderbegas’ were released with a high school diploma. The others ‘dried up’ along the way.

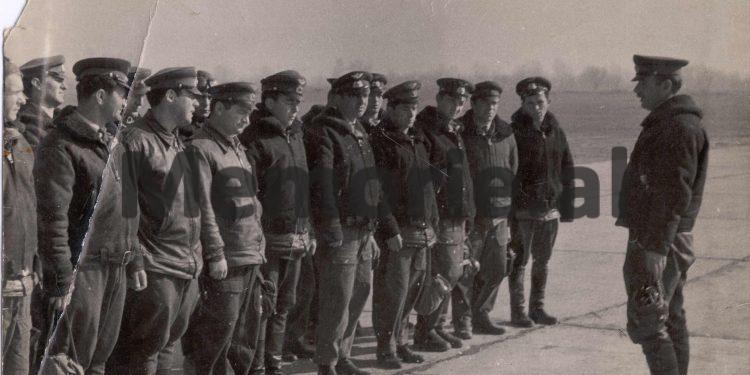

We took the high school exams and went through several tests aimed at determining each person’s future. From these analyses, where medical and psycho-physical tests took first place, 10 students were earmarked to go to the Aviation School in Vlorë, where they would be prepared as pilots. Luto Sadikaj and I were included in this group. A military bus was waiting for us at the school gate. An old pilot had come from Vlorë to accompany us, who had studied in the Soviet Union and had been a partisan. The pilot who would accompany us was handsome, agile, and the uniform he wore suited him beautifully.

We had taken our places in the bus and were waiting to leave. Our companion – I don’t know why – read us a quote by Joseph V. Stalin, according to which: ‘Pilot means: concentration of will, character, and ability to go into danger…!’ After telling us the quote, the pilot addressed us with the words: ‘Whoever accepts this alternative let them come; he who does not accept it can get off the bus!’ I was sitting next to Luto; we looked each other in the eye. ‘I am getting off,’ said Luto, ‘because the Partizani senior team has asked for me!’ Further, he added: ‘From my family, nobody knows that I am going to become a pilot!’ As you wish, I told him; but look; you will play football for 10-15 years, then what? Even I, who exercise in gymnastics, will leave that. Where we are going, there is no suitable place to train. At my words, Luto changed his mind and we set off to become fighter pilots.

The living and learning conditions at the Aviation School were more difficult. If we faced them successfully, it was thanks to the tempering we had done at the ‘Skënderbej’ school. It made quite an impression on us that from the very beginning, as soon as we started lessons, inside and outside the school, there was talk only of difficulties and dangers. We heard talk and rumors about abandoning the airplane with a parachute, about rockets, cannons, and bombs, etc., etc., high-risk elements. After the eight-month theoretical preparation, where we learned various subjects aiming at knowing the constructive side and the ground and air utilization of the initial training propeller airplane, the ‘Yak’-18A, we then moved from the auditoriums to the flight starts.

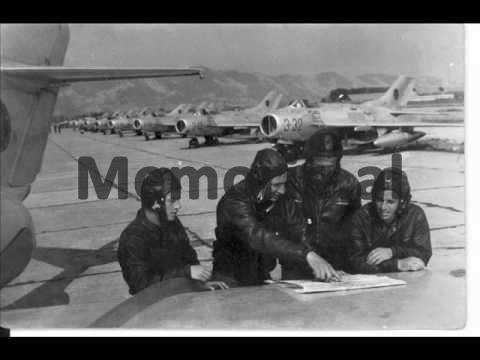

We were the first course that would start and finish the aviation school in the pilot profile here in our country. Until then, pilots had been prepared and specialized in Soviet and Chinese aviation schools. We were all teenagers. Our theory and flight instructors, especially the latter, were young like us. In the group of students who flew the propeller airplane, there were initially 25 of us; five of whom did not earn the right to continue further. In 1965, we moved to the ‘MiG’-15 Bis jet airplane. It was a beautiful, serious airplane with tactical-technical data of the time.

We too had grown and were no longer beginners. Both in theoretical lessons in the cabinets and in the green field where we performed flight practice, we showed good quality indicators as a group. Luto Sadikaj was in the advanced group of student pilots. He ‘dived’ into literature, studied with will and persistence, and in-depth. He rose from his books only when one of us called him to play ball from the olive grove. We would go to the olive grove and play football secretly, as they did not allow us at school out of fear that we might accidentally be physically injured.

In the final year of the aviation school, which coincides with the calendar year 1966, Luto stood out among us in the elements of combat use of the ‘MiG’-15 Bis airplane. His values as a quality pilot were the basic criteria for his appointment as a fighter-bomber pilot in the Aviation Regiment in Rinas. There, Luto initially flew the ‘MiG’-17 F subsonic jet airplanes, with the anticipation that he would soon move to the ‘MiG’-19 S supersonic ones.

Luto Refat Sadikaj was one of those persistent boys in aviation, with a rare will aiming for rapid progress in the pilot profession. His developed physique was on his side. He faced and won by transitioning, at the same time, to two jet airplanes: the ‘MiG’-17 F and the supersonic ‘MiG’-19 S. This was unprecedented and unseen in our country. The event in question belongs to the year 1968, when Luto Sadikaj and three others were selected and stood out among the eight pilots of his group.

In 1969, rumors began to circulate in our country that Albanian aviation would be equipped with sophisticated airplanes of the ‘MiG’-21 types. The wind of further modernization of the country’s military-air fleet with airplanes of the time was blowing. The airplanes in question were to be obtained from distant China. To master this new type of airplane with its utilization features, a group of the most advanced pilots and a group of technicians and specialists, also with suitable data and qualities, were sent to the Asian country.

In the group of pilots, three were younger in age and with fewer flight hours than the main part of their comrades. Among them was Luto Sadikaj. Surprisingly, at the last moments before departure, an order from above shifted Luto from the list, and in his place, a pilot with longer flight experience was appointed. This shift did not have to do with Luto’s flying abilities, which were at the highest levels, but that was the judgment of those who had the competence.

Those selected from our group (Vangjel Koroveshi, Luto Sadikaj, Petrit Bebeçi) stood higher in comparison to some more experienced ones regarding air skills. In January 1971, in the Albanian sky, for the first time, the silhouettes of ‘MiG’-21 supersonic airplanes were seen, which day by day gained the status of ‘Masters of our sky’ and became the pride of our country’s air forces. On May 1 of that year (1971), over the holiday tribune on ‘Dëshmorët e Kombit’ Boulevard in Tirana, 5 arrows paraded from the air in parade formation. They were the MiG-21s, piloted by Albanian pilots. Those who watched them experienced an unseen beauty and felt a legitimate pride and pleasure. Memorie.al