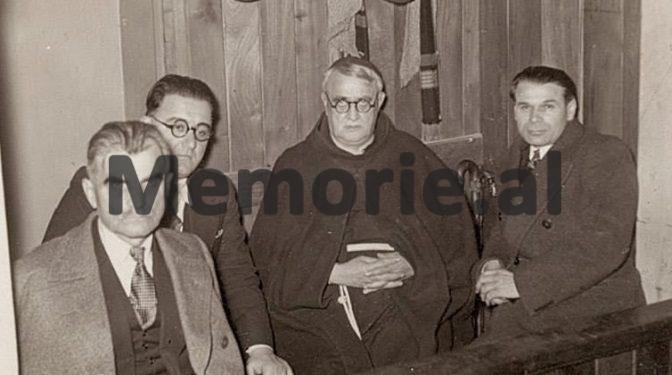

Memorie.al /Ernest Koliqi’s thoughts and evaluations of Fishta hold a special place in his oeuvre. Koliqi was bound to Fishta by many ties, and from the very dawn of his literary contribution, he remained a devoted admirer of the master and his work, serving as its translator, critic, and scholar. The first consideration of Fishta’s work was expressed by Koliqi in a lecture delivered on January 18, 1931, at the Saverian Salon, later published in the magazine “Leka” under the title “The Mission of Young Albanian Literati.” In this speech, Koliqi refers to Fishta as “the last epic poet of Europe.” Nearly at the same time, Koliqi dedicated a poem to Fishta on the occasion of the poet’s 60th birthday.

It was published in October 1931 in the magazine “Hylli i Dritës,” where, through his verses, Koliqi synthesizes the extraordinary values of Fishta’s contribution. In these lines, Koliqi poured rare reverence and human warmth, expressing powerful emotions such as: “Singer, O leader of music, O soul of a thousand voices, / your lips trembled with sweetness… and you invented all the graces of our tongue, to sing of a noble lady, who captured your generous soul with beauty / and you dissolved sometimes in joy and sometimes in woe, for the only love, called, O Fishta, Albania…!”

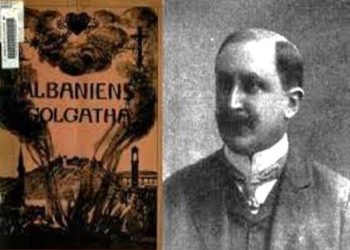

A year later, in 1932, Koliqi published a study on two songs of The Highland Lute (Lahuta e Malcis) in the magazine “Minerva,” titled “Marash Uci.” It should be noted that following the 1925 publication in Shkodër of a detailed and highly valuable study by Cordignano titled “The National Epic of the Albanian People,” dedicated to the songs of the Lahuta, Koliqi can be counted among the first scholars of Fishta’s major work at a time when it had not yet seen its first integral publication.

This early writing by Koliqi remains among the best in the critical reception of the poet’s work. Even in this study, a deep knowledge of the poet’s oeuvre is evident. He distinguishes Fishta from other authors of Albanian Romanticism because, as Koliqi observes, Fishta is not interested in the landscape but in the hero – the world of the Albanian highlander – which makes his work unique and authentic. This article is notable for its accurate assessment of Fishta’s creative code.

Although at the beginning of the study he speaks of the monotony that the use of the octosyllabic verse (which he calls the national verse) might bring, he notes that in the hands of a master like Fishta, it shines. He writes: “The powerful flow of the octosyllabic rhythm astounds the mind. The soothed ear yields to the delight of the harmony of the syllables, and the soul feels only that indefinable vibration gifted to us by music. In Fishta’s work, the word is seen as an enchanting sound rather than a mere creative expression.”

In this writing, Koliqi finds it appropriate to employ theses of psychoanalysis and intuitionism in criticism, speaking of the role of intuition and the poet’s inspiration that springs from the depths of the subconscious and miraculously melts into his peerless art.

Koliqi was among the first to defend the idea that Fishta’s foundation lay in the rich Albanian folk epic, a thesis he would further develop throughout his scholarly work. Cordignano had written as early as 1925 that: “To fully judge a poem of this kind, the entire culture of the Balkans must be known” (The National Epic of the Albanian People, Shkodër, 1925, p. 77).

Following this path, Koliqi was among the first to speak of the influence of Croatian poets Kačić and Mažuranić on Fishta, underlining the idea that through his original experience, he created a new epic style – one that could be called “Balkanic” – because in the fabric of his poetry, epic, lyricism, and satire are startlingly interwoven, giving a completely unique shape to Fishta’s art in his masterpiece.

In interpreting the values of Fishta’s work, Koliqi was among the first scholars to uncover the complexity of the poet’s work. Beyond the historical argument and the sharp inter-ethnic conflict, he viewed the work in its literary-cultural aspect as part of both Albanian and Balkan cultural history.

In this paper, Koliqi highlights the connection between the poet’s work and mythology, noting the master’s striking ability to functionalize mythological models and material “presenting modern people and events,” as Koliqi says, “surrounded by the vapors of antiquity,” thus touching upon one of the significant features of the poet’s work from the perspective of modern criticism.

In the collection published on the first anniversary of the poet’s death under the auspices of the magazine “Shkëndija” in 1941, Koliqi published the outline “Fishta, Interpreter of the Albanian Spirit.” According to him, every poet has their creative vocation, and poets, like nations, have their own individuality. In Fishta, he sees a striking individuality because, unlike others, “he discovered the most characteristic Albanian life, the life of the highlanders.” Fishta’s work captures the quintessential Albanian of the “cornbread.”

According to Koliqi, “Fishta’s rare poetic force and his penetration into Albanian life make his work a true encyclopedia of the genuine Albanian world.” He particularly emphasizes the role of the poetic form, stating that “both the words and phrases in Fishta’s work seem to erupt from the mouth of the people.”

Koliqi’s theses from the early 1940s – viewing Fishta’s work as a “true encyclopedia of the Albanian world” and as “the most titanic effort the Albanian has made thus far to reveal his own world to himself” – can be considered among the most valuable insights in the critical reception of the poet’s work during the peak of his fame.

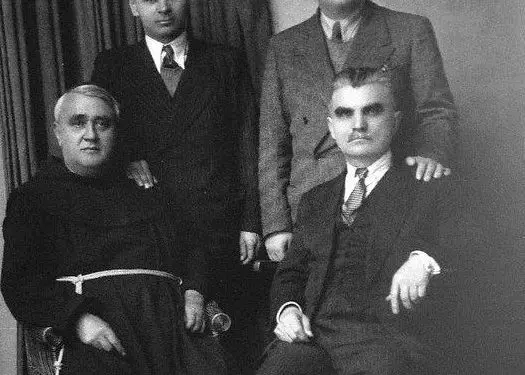

These studies alone would suffice to grant Koliqi a prominent place in the evaluation of Fishta. However, it is equally significant that for more than 40 years of political exile in Italy, Koliqi bore the primary weight of promoting Fishta’s name and work, which were denied and anathematized in his homeland. He did this in both Albanian and non-Albanian circles.

He worked tirelessly to translate Fishta’s work into Italian, articulated important new theses regarding the master’s creative originality, and highlighted the significant place he occupies in the constellation of the greatest Albanian writers. He published all of this in Albanian and foreign languages, always with striking objectivity, far from bias, and with a highly cultured sense of polemic.

In the magazine “Shejzat” alone, which he published for 18 consecutive years, he printed six songs of the Lahuta in a masterful Italian translation, published portions of Fishta’s prose, and published/republished about ten outlines and studies that form a “golden necklace” in the critical reception of the master’s work – all realized at a time when the poet’s work was violently banned and excluded in his homeland.

Fishta was commemorated in the pages of the magazine on the 20th and 25th anniversaries of his death, and the 90th and 100th anniversaries of his birth. Notable writings include: “Albania’s Three Greatest Poets,” “Fishta’s National Apostolate,” “Fishta is Alive among Us,” “The Voice of the National Poet,” “Fishta as a Man and a Poet,” and “Fishta in the Service of National Politics.”

The thoughts expressed in these writings – such as: “The Fishtian poetic power that flows and floods the Lahuta has its source in the depths of oral literature,” “The matchless voice of an entire nation,” “He who denies Fishta, denies the essential idea of the Albanian National Renaissance,” and “Few poets in the world suffered the paradoxical fate of Fishta” – have now acquired the status of unique definitions due to their objectivity and scientific literary originality.

Koliqi finds Fishta’s superiority as an epic poet (the genre he focused on most) in his revitalization of the vitality of Albanians, who never succumbed even when history put them through trials that questioned their very existence. But they stood firm, and they are there, Fishta asserts with his masterpiece “The Highland Lute,” soaking his work with a rare love for his homeland and his people.

This is precisely what Koliqi’s following consideration expresses: “Other poets touch and charm us with musical magic, metaphorical brilliance, poetic emphasis, or superiority of thought, but none like Fishta awakens and stirs within us the qualitative ferments that harbor the vital mystery of the Arberian blood.” A special place in Koliqi’s contributions as a literary scholar is held by the work “The Two Shkodran Literary Schools,” which began publication in “Albanie libre” in 1953.

This unique work, dedicated to the contributions of the Jesuit and Franciscan Fathers, contains valuable information and data on the development of literature, its meaning and function, the relationships between the creator and the reader, and the distinguished authors and works belonging to the two schools. As Koliqi himself would state, it could be considered the skeleton of a more voluminous work, which unfortunately remained unfinished.

According to testimonies, Koliqi had set to work on its completion, but his sudden death interrupted it. Fishta’s place and evaluation within the important contributions of the Franciscan literary school are central and unique. Through his work, he embodies the entire patriotic and modern inclination of this school, which laid as the foundation of its creativity everything precious in the national treasury: thought, aesthetic taste, folklore, and the rich language of common Albanians, thus performing a rare honor and service to his nation.

In this work, Fishta is the personality for whom Koliqi expresses and defends his views, affirming his status as the national poet. Meanwhile, in his study written in Italian, “The Three Greatest Poets of Albania,” Koliqi evaluates Fishta alongside De Rada and Naim Frashëri, each having their unique vocation, different sources of formation, and distinct roles in literary developments. What Koliqi emphasizes in his evaluation is:

“These diverse poets are the language of a flaming spirituality, three branches of a single root, of the traditional trunk. They are the sincere and wonderful voice of the soul of a people where Islam, Orthodoxy, and Catholicism harmonize in the voice of the old common language and in the roots of a common brave blood.”

The visionary Koliqi has the merit of not only studying, defending, publishing, and translating Fishta’s work but also foretelling the rebirth of the poet’s fame after a long period of anathema. He waited a different time for Fishta, who “miraculously made the vision of an Albanian Albania bloom in our souls.”

His astonishing prophetic conviction awaited and experienced this time when he wrote: “But how can the voice of the Lahuta fade into silence, when it knows how to dig into the secrets of our souls to awaken the most precious, typically Albanian feelings, nourished by our purest blood?” For Koliqi, Fishta fully deserves this, because “he taught us to love Albania like a bride of the soul” and because he is “the matchless voice of an entire nation.”/Memorie.al