Memorie.al / There are several scholars, activists, and clerics who, alongside the professional duties for which they were educated, dedicated a part of their lives to the development of Albanian culture. They worked in the most remote corners of our homeland, in those areas where the sun, obstructed by the mountains, shines for only a few hours. One of them was Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi. The difficulty of his work was realistically described by the scholar and polyglot Faik Konica, who in 1930 published “Memories of Shtjefën Gjeçovi” in the “Dielli” newspaper of Boston – a piece that was later included in the publication of the work “The Code of Lekë Dukagjini” (Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit).

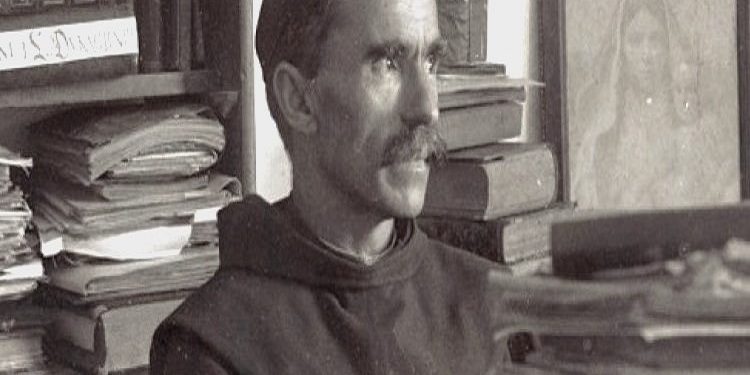

Among other things, the author wrote: “In 1913, I went to Shkodra…! (It was a proposal by Father Gjergj Fishta to pay a visit to Gjeçovi, author’s note). The idea of a visit to Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi in Gomsiqe pleased me immensely. Thus, without wasting time, we set off. One thing to note, which filled me with wonder and sadness, is that from Shkodra to Gomsiqe – a seven or eight-hour journey by horse – we found neither village nor house, save for a poor inn where we stopped for a coffee. Nowhere did we see any sign of life; a void and desolate place, as if forgotten by God and man.”

“But the weariness of the journey was rewarded beyond hope as soon as we arrived in Gomsiqe…! The parish house, a stone building, bright and clean, half-empty of furniture but filled and adorned by the great heart and smile of the host, stood welcoming and quiet by the side of a river. Here lived Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi. Here he spent his life amidst prayer and studies, one of the most distinguished men Albania has ever had.”

From his life…

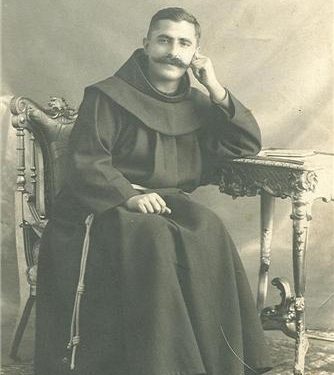

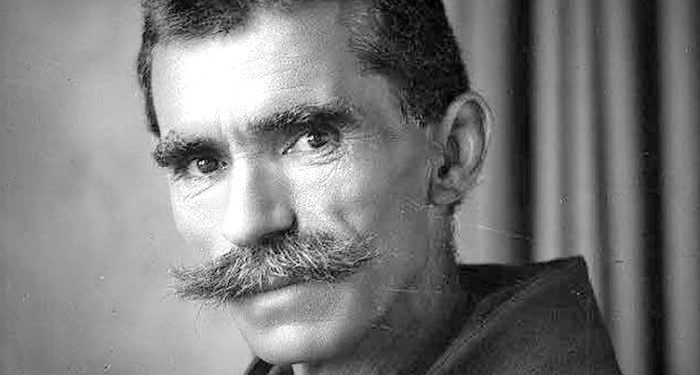

The writer, ethnographer, archaeologist, translator, patriot, cleric, and “Teacher of the People,” Shtjefën Gjeçovi, was born in Janjevo, a poor village in Kosovo, on July 12, 1874, and was murdered in Zym, Kosovo, on October 14, 1929, by Great-Serbian chauvinists. After attending the Franciscan College of Troshan – a beautiful village in Zadrima – for some time, he continued his studies in Bosnia and Croatia in 1888.

Upon returning to Albania, his feet would tread through dozens of villages, serving as a parish priest in Laç i Kurbinit, Troshan, Gomsiqe and Gojan, Theth, Shalë and Shosh, but also in Peja, Gjakova, and Prizren, as well as in Shkodra, Vlora, Durrës, and Zara. He participated in organizing anti-Ottoman uprisings in the early years of the 20th century and was among those patriots who strongly condemned the de-nationalizing policies of Serbia and Montenegro, as well as the Austrian occupation of our country.

He was not only a writer but also an archaeologist and ethnologist. He was a distinguished collector of folklore, rare vocabulary, customs, traditions, and rites. Simultaneously, he was a translator. Many of his works remained in manuscript form, a portion of which is preserved in the State Archives in Tirana, the Historical Museum of Shkodra, and the “Marin Barleti” Library of that city.

Gjeçovi was also a corresponding member of the ‘Albanian Literary Commission’ of Shkodra (1916-1928). Initially, Gjeçovi used the pseudonym “Lkêni i Hasit” in the poems he published in the magazine “Albania” – this masterpiece of Albanian journalism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, directed by Faik Konica.

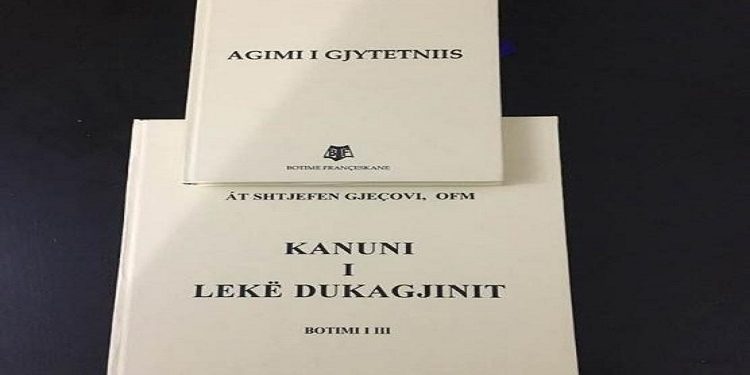

Later, the work “Agimi i Gjytetniis” (The Dawn of Civilization) was published. Naturally, Shtjefën Gjeçovi’s most monumental work is “The Code of Lekë Dukagjini”, published posthumously in Shkodra in 1933. This edition is preceded by a short biography written by Father Pashk Bardhi and continues with a long preface by Gjergj Fishta, which concludes with these words: “I wrote this much not so much to extend a preface to this work, as to express the boundless longing I have for its unforgettable author.”

The Work “Agimi i Gjytetniis” (1910)

This work, published a century ago in 1910 in Shkodra, consists of 144 pages. It is preceded by a Latin quote taken from the humanist Marin Barleti. The author then includes a dedication to Gj. Fishta, writing: “To Father Gjergj Fishta, O.F.M., author of ‘The Highland Lute’ and many other writings, as a token of national friendship, the writer dedicates these pages of patriotism with affection.”

Gjeçovi follows with an appeal addressed to Albanians titled: “Beloved Albanians!” He begins with a quote from Pjetër Bogdani’s work “The Cuneiform of the Prophets” and continues with his own assertion: “I mean to say that I brought nothing of my own in these few lines, but only what I borrowed from others. Be that as it may, accept this book, O patriot brother, and keep it as a gift that springs from the core of the heart of him who greets you and salutes you in the Albanian way,” Gomsiqe-Gojan i Poshtëm in Mirdita, January 14, 1910.

The book has four parts plus a supplement. Part I is titled “Society” (pp. 2-30); Part II “Faith and Homeland” (pp. 31-60); Part III “Patriotism” (pp. 61-99); Part IV “Language” (pp. 100-124); and finally a ‘Supplement’ dealing mainly with problems of the Albanian vocabulary (pp. 125-137). Part IV, titled “Language,” considered a true hymn to the Albanian language, is certainly one of the most interesting and valuable parts of “Agimi i Gjytetniis,” as it was written two years before the declaration of national independence, when the issue of the Albanian language – its preservation, development, enrichment, and dissemination – was at the forefront of the cultural, educational, and patriotic landscape.

This served the awakening of our people in the struggle for national liberation; it was in the spirit of the Enlightenment ideology and the views of our National Renaissance figures (Rilindësit). The author titled this section “The pillar of Albania’s schools shall be the Albanian language” and divided it into 10 points. In this part, the author dedicated himself to the values and importance of language as the primary element distinguishing the identity of one nation from another – something for which his predecessors, Veqilharxhi, Kristoforidhi, Naim and Sami Frashëri, Çajupi, Fishta, or Mjeda, had valued, glorified, and sung to in their creations, which undoubtedly influenced the author.

This was also dictated by the circumstances of the time, when the pressure from the language of the occupier and the neighbors was immense. Therefore, Albanians had to be sensitized. Being Enlightenment thinkers, the Rilindësit initially prioritized the cultural factor; thus, the values of the mother tongue had to be highlighted, alongside the necessity of its preservation, enrichment, and use.

With a very laconic style, the author synthesized in a few lines everything a person – and specifically an Albanian – needs to know, as the writer notes: “…language is something that cannot be bought, sold, or exchanged; it is a thing that must be guarded like a precious stone, a special gift from God and an inheritance from our ancestors… it must be guarded like the light of one’s eyes…! This gift is the Albanian language.” He ends the paragraph with this aphorism: “As much as the sun can be conceived without light, so can a nation be conceived without a language.”

All the paragraphs of this section, which are separate issues, are linked by a core theme. Gjeçovi demanded that, under the conditions of occupation, the cultivation of the spoken Albanian language should take on special importance, illustrating this with examples from family life. In another paragraph, he raised a rhetorical question: What is language? The author provided the answers himself. Furthermore, Gjeçovi noted the benefits and honors that language brings. He considered it the main feature that distinguished a nation, which “keeps the nation alive, being the first and only sign by which nation is separated from nation.”

In the situation of the time, a negative phenomenon was observed: many Albanians were occupying themselves more with foreign languages than with Albanian – a phenomenon treated by other Renaissance figures, contemporaries of Gjeçovi, and later. Such an action did not serve the political moment and the ideology of the time, when we were on the brink of declaring independence. This damaged the image of the struggle for the final goal, devalued the mother tongue, and harmed the homeland and the nation. In this paragraph, influenced by the worldview of the Rilindësit, he gave another aphorism of monumental value, also shared by Naim Frashëri: “The language of a nation has no stopping, nor can it ever be stopped.”

For the author, the primary duty at those moments was to learn the Albanian language, to speak it without errors, and to cleanse it of foreign words, which would make the language flourish and beautify. Gjeçovi was fully under the influence of the Renaissance worldview and kept in mind Naim’s instructions in “Homer’s Iliad,” which stated: “Our language must be written purely in Albanian, for foreign words disfigure it greatly. Our language is vast and very beautiful; it has very good words to replace foreign ones.”

He asked that we learn the Albanian language, and for this, he brought some verses from what the author calls “the golden-handed Frashëri”: “The language of the motherland learns; / It can enlighten you, / other things you may chant / But keep that one as your lady.”

Gjeçovi would always touch upon the Albanian’s need to learn the language and not focus on foreign tongues. He criticized those Albanians who, by valuing and learning foreign languages, despised their mother tongue. The author used his entire arsenal of skills to make such a hobby loathsome and to direct them toward Albanian. He by no means agreed with such a phenomenon, emphasizing that the people put these individuals “at the tail of the lute” (at the end of the line) and say: “Oh, how gracefully he speaks, as if he were a Latin bird. While that language, which God, nature, and our mother taught us, we want and strive even more to erase from our hearts.”

Gjeçovi, filled with resentment against such an action, pointed out a phenomenon occurring in those years, where in Albanian schools, foreign languages, as the author says, took the “head of the table,” while the Albanian language remained “insulted and despised.” The Albanian language, which we inherited from our ancestors, “we are despising and leaving like a luckless cuckoo on a dry branch; and our hearts do not burn with pain for it!” Why become the laughingstock of the world, the author shouted, when we are in our own land and have our own language.

The Albanian language needed care. And this would be done by Albanian patriots, as Albania was occupied and, along with it, the Albanian language. But Gjeçovi was an optimist. For him, “unless our nation goes extinct, the language cannot go extinct.” To love the language, we must take care of it. There was no need for rifles, “to grab the sword”; “today required work and the sharpening of the mind,” Gjeçovi emphasizes. For Gjeçovi, it was unforgivable that foreigners were interested in the Albanian language while Albanians remained cold and foreign to this language, which was a gift from God. It was not enough just to claim “I love the language,” but one must delve deep, know it, and discover its beauties.

Another issue touched upon by our Renaissance figures was that of a common language. Although Albania had not yet gained independence, Albanian patriots, alongside preserving and spreading the language under occupation, began to prioritize the unification of the language. Even the press of the time did not remain indifferent. We refer to only one organ that circulated in those years: “Diturija” by ‘Lumo Skëndo’ in 1909, in an article titled: “Will we have a single literary Albanian language?”

Its author not only presented his opinion on this problem but also provided ways to solve the issue of the literary Albanian language, emphasizing the idea that a dialect should be at its base, although the reality of the time did not favor such an idea. In these circumstances, for the author, it was better to use both dialects of Albanian. However, it was required to have a common Albanian language, as the languages of civilized nations had – one alphabet, one orthography, one terminology – otherwise, the nations near us would swallow us up.

Scholar Ruzhdi Mata observes that Gjeçovi set the task of creating a common Albanian language, overcoming the dialectal divisions of a language, to contain all the great wealth created by the people. He did not agree with the situation of that time where everyone was drawn to their dialectal speech – although he himself wrote in Gheg – as confusion would arise in communication between Ghegs and Tosks.

For this, the author advised using “the pure language, the school language,” because; “Without the school language, no saying and no thought can be uttered by our mouths. Our word, spoken with errors, will not be able to have the power to fill the mind of our companion for this or that matter.” Gjeçovi took his idea further, following completely in the footsteps of our Renaissance figures. He called for unity between Ghegs and Tosks – a non-divisive idea, but a very important and mobilizing one on the eve of national independence.

“Ghegs and Tosks, brothers! Let there be unity among us, unity in speech and unity in writing; unity keeps us in union, it increases our power.” Regardless of the author being from the North, his patriotic feelings in the field of language were reflected in his views, which increased Gjeçovi’s value in this regard as well. Nevertheless, as a true patriot, he insisted that under those conditions of occupation, we must preserve and learn the Albanian language inherited from our ancestors, using it in every office or in every corner, because, according to Gjeçovi, “Homeland and language, thought and word, word and life, are three things tied by a chain, and one without the other cannot exist.”

Gjeçovi dedicated attention to the importance of the dictionary for learning the language, primarily Albanian, which he treated in the final part titled “Supplement.” Initially, he noted five Albanian dictionaries: Bardhi (1635), Rossi (1886), Jungg (1895), Kristoforidhi (1904), Luigj Gurakuqi (1906), and the “Bashkimi” society (1908). For the author, the importance lay not in the accumulation of books, but in reading them, for thus the Albanian would learn the language, because “Language unites the people of a nation.”

Gjeçovi rose against the ignorance of those Albanians who said: “My mother taught me Albanian, I don’t need more since I know it!” Here the author intervened by distinguishing, as he wrote, between “domestic language” (giûhë shpijare) and “civilized language” (giûhë gjytetnore). The first belonged to household discourse, an unrefined and unprocessed language, while the civilized one is processed, with a rich vocabulary, and is selected. This was found in the spring of the people, in the dictionary, which “is a sea that never ends!.. it is the treasure of language, of knowledge, of events, of versification and poetry.”

Mastering the vocabulary meant that “the language beautifies us both in speaking and in writing.” Gjeçovi was also against foreign words, whose influx was not small at that time when there was no Albanian state. In these circumstances, Kostandin Kristoforidhi’s dictionary had to be valued and used, as according to Gjeçovi, he had set apart foreign words in the dictionary. He also referred to the Hungarian historian Lajos Thallóczy (1854-1916), who had said that Albanian has no connection with other languages and is one of the oldest languages in Europe. Gjeçovi closed the work with the instruction to learn the dictionary of the Albanian language, as it is “the book of our nation and the treasure of our homeland.”

Gjeçovi’s work was valued by his contemporaries for its language, far from foreign influences, rich in vocabulary and phraseology rarely found among other writers writing in Albanian. The writer, ethnographer, archaeologist, translator, patriot, cleric, and “Teacher of the People,” Shtjefën Gjeçovi, remains an important figure of our Renaissance, who devoted himself with self-sacrifice to our national cause and specifically to the preservation and dissemination of the Albanian language and our national education – being a pioneer in opening many schools in the mother tongue, as a creator, and generally as a collector and systematizer of the material and spiritual culture of our people and nation. / Memorie.al