By SAMI REPISHTI

Part Three

“In Albania, the communist crimes of the past have not been documented or punished; there has been no ‘spiritual cleansing,’ no conscious confession or denunciation of the ordinary communist criminals!”

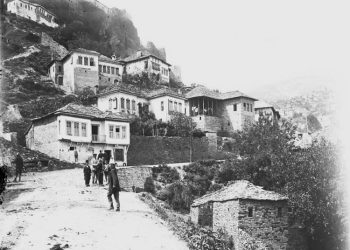

Under the Shadow of Rozafa

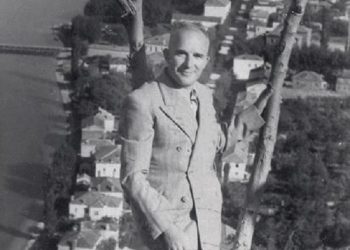

Memorie.al / During the 1930s and 1940s, with the relentless fascist and communist onslaught on Europe, sooner or later, the “fate” also seized the Albanian nation. Like all young people, I found myself at a crossroads where I had to take a stand, even at the risk of my life. At that moment, I said “no” to the dictatorship, took the path that seemed endless, a sailor in the vast sea, without shores. The rebellious act that nearly killed me simultaneously liberated me. I am an eyewitness to life in the fascist and communist hell in Albania, not as a “politician,” or a “personality” of the macro-political landscape of Albania, but as a student, as a young person who became aware of my role, at that time and in that place, out of love for my homeland and the desire for freedom; simply, as a young person with a pronounced sensitivity, loyal to myself and to a life of dignity.

Continued from the previous issue

IV

On April 7, 1939. Before the light of dawn had appeared, a distant cannon fire woke us early. The Albanian land was being struck with fury. Warships and airplanes enacted the first act of a bloody drama that began that day. A modern army trampled our land. The foreign occupation began! From the open windows of the room, the sound of artillery entered, while in the unprotected sky, the Italian bombers flew. I left the house. I wandered through the streets of the city with friends, aimlessly, without purpose. The city had no life. The fear of the occupying forces’ revenge on the innocent population was evident everywhere. That night, sleep had disappeared for all. Exhausted, I felt that after this event, I would never again enjoy the peaceful sleep of carefree years. The next morning, the sounds of gunfire were heard at the city entrance, initially isolated, later uninterrupted. I felt restless at home. I went out. The main square was almost deserted. I saw only a few unarmed soldiers. The officers had fled the city. It was a mournful sight!

At noon, the gunfire ceased. No one knew anything for sure, but it was understood that the enemy was at the city gates. We rushed to the Rozafa fortress, behind which was the entrance bridge in Shkodra. Italian soldiers were placing long trains to cover the damaged part of the bridge. We approached. The square was filled with cartridge cases from the ammunition used. It was clear that the area had been a battlefield for several hours. We looked in amazement at the iron helmets decorated with feathers of the bersaglieri, which appeared ridiculous. We crossed the damaged bridge. On the other side, where the Italian battalion was congregated, inside the bakery, lay the bodies of two Italian soldiers: a lieutenant and a soldier. Their bodies were covered with a tricolor Italian flag. A little further away, in a row of portable beds, the wounded soldiers groaned. Before the corpses, I felt no remorse. Later, I began to feel ashamed of such a stance, and a feeling of sadness enveloped me. Death frightened me. A coldness I had never felt before gripped my heart at the sight of this painful scene. With my thoughts about the misfortunes of these soldiers, victims of a dictatorial regime, I also felt a sense of pride that this ‘slap’ was given to the aggressor. The hatred ignited in our hearts by the treacherous attack transformed my true nature…!

From the road leading from the city, a row of cars was heading toward the bridge. Before they arrived, I recognized some faces. The corrupt or politically deceived element played its lowly role in this comedy prepared by the foreigner, spreading lies around the world about the “friendly welcome” that our country offered. The bridge was covered. Immediately, the march of the Italian troops began. From our side, representatives of the “fifth column” hurried to greet them. At the head of the bridge, where the blood of the fallen had been spilled, occupiers and traitors shook hands with one another. They celebrated the victory, giving speeches. Embraces, congratulations, loud laughter. “They” had triumphed. “We” lived through the first act of the tragedy of foreign occupation. The division was complete!

Days flowed quietly after the storm that engulfed the country. Talk of resistance was heard at the beach of the port of Durrës; the figures of Mujo Ulqinaku and Bazi i Canës were exalted, but no one was able to name other victims. In the city, the market opened, offices were reopened, and students began their lessons.

In our high school, there were two professors missing. The Frenchman left immediately, and the light-haired professor who spoke to us before the Italian invasion had fled. In every classroom, the photographs of these two men, foreign to us, seemed to guard us day and night: a puppet king and a monkey dictator. The first contact and clash we had with the occupier came with the arrival of the “fascist instructors” and their attempts to incorporate us into organizations of a type unknown to us. From the first days, a coldness was felt. Almost without exception, all students at the school were enveloped in a silence and distrust that made us suspicious of everything. The black color of the uniforms we were forced to wear for the celebrations and demonstrations reminded us of the soldiers of the early days of occupation. This growing distrust became the seed of passive resistance, silent, which contained within itself the core of the armed resistance that would come later. A sense of a common and general danger gave rise to the need for closeness among us, the need for solidarity that we experienced during the days of demonstrations. On its part, the occupier began the policy of denationalization, eliminating the symbols of independence. Our land was called inseparable from that of the occupier.

The foreign king became our king. The signs of the fascist licensor entwined our flag; the black shirts became the official uniforms. The administration was subjected to the control of fascist hierarchs, while the governmental “marionettes” rose and fell in government, according to the degree of their submission to the foreigner and the paid service. New laws legitimized aggressive acts, supplemented by governmental decrees and orders. The intentions of complete subjugation—Italianization and fascism—were clear! In school, educational programs underwent significant changes. Fascist doctrine took precedence. Foreign professors replaced Albanian teachers, who were removed. Books, magazines, and newspapers flooded our libraries. Everywhere, from the capital to the most remote village of our homeland, a rapid wave of fascistization spread like a black shadow of the night. Alongside the deafening noise of the “civilizing mission” proclaimed by the foreigner, the local servants rushed to take action to retaliate, taking the necessary measures to prevent any resistance. Young and old were arrested during the night, ending up in prisons and internment camps of Italy.

There, far from their homeland, in the dark prisons of fascism, where for decades, worthy sons and daughters of the Italian people lay mercilessly, the first groups of our compatriots began to appear. There, in the cells of the fascist prisons and camps, where men and women of both oppressed nations perished unjustly. The seeds of brotherhood were sown. There, a common antifascist language was found, the language of every individual’s right to live free. There, two peoples encouraged by fascism, for animosity, understood each other best, experiencing the weight of oppression and the desire to be free together every day. There, the solidarity of the oppressed became unbreakable! The school year was approaching its end, but the joy that had once filled our hearts was gone. The occupation caused significant changes. It seemed we were living in a foreign world, a world that did not adapt, that restricted us, tormented us, and threatened us. The first signs of an incompatibility with the situation that had been created were evident. From the very first days of the demonstrations, we had been thrown, without return, to the other side of the barricade. Later, protests against the occupier became massive and organized. The use of violence by the fascist police increased. We began to record the first victims in our ranks. We had entered the field of armed battle without weapons but with an unwavering belief in the justice of the cause we had embraced.

Within ourselves, we felt invincible! The idea of national unification had been created. The sense of solidarity among us grew every day. A great desire was developing to offer help and support everywhere, as a need for action, to do something, everything that could advance our struggle. In the early days of July, with a few personal belongings and in the company of a well-known mountaineer, I set out for summer vacations in the mountains. I knew that in the home of my host, life was difficult, but in that house, in its harsh poverty, I would also find “bread and heart,” offered with a traditional friendship that was indescribable and for which our people are rightfully proud. The difficult road passed through the mountainous area. Since the early days of this country’s history, stubborn and unfortunate mountain men earned their bread with sweat and blood together. Tall and rugged mountains, some forested in beauty and others completely barren, deep valleys that rarely saw the sun, rushing streams flowing with a deafening noise, birds fluttering that never ceased to fly, and a fresh forest breeze that brought sweetness to our faces, the clean air that delighted, was enchanting. In this endless natural grandeur, I felt small and began to feel fear…!

Our animal walked calmly and securely in front of us. Behind it walked the mountaineer whom I was following. I tried to compare these giant mountains with the harshness of their inhabitants, like my mountaineer friend, a tall man with a sturdy build, a drawn face, dark eyes, a broad forehead with thick eyebrows, short and unkempt hair, tied back with a brightly colored scarf over one eye, a large nose, slightly crooked and uneven, a regular mouth with thin lips, and a neck that barely showed because his beard was untrimmed. A pair of twisted mustaches suited this face, where a smile could rarely be seen, marred by the marks and wrinkles left by the struggles of daily life. He walked effortlessly ahead, his head lowered to see where to place his foot, and the rifle slung over his shoulder, singing in his traditional manner songs that sounded more like laments. And as if he wanted to break this monotony, he occasionally called to the heavily loaded mule that, accustomed to this voice, walked unhindered. Often, with a familiarity that seemed unexpected when emerging from such a harsh nature, he turned to me and said: “Are you tired? We can rest if you want…! I forgot that you are a city boy…! Do you see where we live?” He laughed. When the evening darkness became complete, we entered the village of Repisht.

From a house that was hardly distinguishable, a small light appeared, and a few steps that approached became clearer. I heard the greeting of the woman and the voice of the mountaineer saying, “We have a guest!” The woman immediately stepped aside, and while holding the small light with her left hand, she extended her right hand to welcome me. “Welcome,” I replied. I asked for permission to sleep without dinner, and from the exhaustion that had overwhelmed me, I fell into a deep sleep until late morning. In the sunlight, two small windows allowed limited light to enter, and I looked in astonishment at this house, which was my host’s “home.” One single room! One single door! A hearth fire on the front wall, two utensils for the needs of bread and dairy, and work tools. The poverty could not have been any more complete! I looked at the roof, in this building without a ceiling, full of holes and daylight. The unplastered walls, the windows without glass, just covered with wooden shutters, a floor partially covered with planks and the rest bare earth, a void and poverty that could break the spirit, brought to mind the cold smell of the autumn rain and the harsh winter in this house that was more of a shelter for animals. I could not understand how it was possible that such deprivation could exist in a village just six hours from my home, among people I saw every day in the city?!

From the straw bed where I slept, I looked around without the moons falling down. I observed everything again carefully, deeply touched by endless despair. But my heart broke even more for the children of this family, condemned to suffer, and for the difficult future that awaited them. They were small, growing up in an extremely poor family, in a lost village, and in an ignorant environment, far from school, far from urban civilization. Through their daily hard work in the fields, they would follow the example of their father, their ancestors, century after century, ensuring, without any change, meager resources for a difficult life. Thrown by fate in this desolate place, where culture and education had not yet found a way, they lived a life that was an unceasing struggle against the harsh and stingy nature. Perhaps, their daily efforts shaped them better, and when life took them through difficult paths, they walked with pride and scorned every danger. Silent heroes!

I got up from the bed! Three little ones who were eating looked at me in surprise. I smiled, and speaking sweetly, I wanted to win the hearts of my three young friends. – May it be good for you! – I told them. They did not respond. Half an hour later, the lady of the house, a robust woman dressed in local garments, after apologizing to me several times for their poverty, offered me bread and milk. My legs hurt from the walking of the previous day.

From the straw bed where I slept, I looked around without the moons falling down. I observed everything again carefully, deeply touched by endless despair. But my heart broke even more for the children of this family, condemned to suffer, and for the difficult future that awaited them. They were small, growing up in an extremely poor family, in a lost village, and in an ignorant environment, far from school, far from urban civilization. Through their daily hard work in the fields, they would follow the example of their father, their ancestors, century after century, ensuring, without any change, meager resources for a difficult life. Thrown by fate in this desolate place, where culture and education had not yet found a way, they lived a life that was an unceasing struggle against the harsh and stingy nature. Perhaps, their daily efforts shaped them better, and when life took them through difficult paths, they walked with pride and scorned every danger. Silent heroes!

I got up from the bed! Three little ones who were eating looked at me in surprise. I smiled, and speaking sweetly, I wanted to win the hearts of my three young friends. – May it be good for you! – I told them. They did not respond. Half an hour later, the lady of the house, a robust woman dressed in local garments, after apologizing to me several times for their poverty, offered me bread and milk. My legs hurt from the walking of the previous day.

V

September 1939. Two world wars within twenty-five years! It was a second slaughterhouse for a continent that had not forgotten the first. Twenty-six years ago, my Shkodra faced a supreme test. Surrounded from all sides, squeezed in a narrowing arc every day, for seven consecutive months, it was torn apart under the fire of the Montenegrin and Serbian armies. Seven months of war, destruction, suffering, disease, and hunger for the population. The mothers of the slain sons still lived in Shkodra; the orphans and widows were still dressed in black. Many bore wounds on their bodies, and mutilated limbs. There were still memories of a not-so-distant past, especially for those who died of hunger. Eight years later, in 1920, the same enemy, in a second trial, martyrized the city with siege, causing the economy to weaken to a point from which Shkodra never fully recovered. Now, on the brink of a fierce conflict, the city watched with fear the approaching storm, for the memories of the horrors lived were still fresh. Shkodra, well acquainted with suffering, had sipped the cup to the bottom and was afraid. However, in these turbulent and perilous days, along with a sense of great anxiety, my city showed its strong pulse like a ball, and a determination that did not allow it to bow down. During those days, this conscious determination of the city of Rozafa inspired me! The Second World War had begun! The world was divided into two opposing camps, and our country was divided as well. On one side were the collaborators of Italian fascism; on the other side was the overwhelming majority of a population that resisted and tied its fate to the victory of the anti-fascist camp.

In the early developments of the conflict, we found very few reasons to rejoice. The victories of the Axis forces were swift and significant. In the midst of this nearly desperate situation, a light of incomparable hope emerged: the British resistance, especially the determination of the population of London, not to surrender to Hitler’s terror. London! Coventry! Names that will never be forgotten, symbols of resistance and the conviction that the enemy would not pass. The BBC radio broadcasts spread the enthusiasm for the resistance of the heroic British, who, entirely alone, put a stop to the Hitlerian divisions with an indescribable courage. Great Britain became our sacred sanctuary, the land of freedom, our most complete assurance against potential victory. “Blood, tears, and sweat!” The British message was clear. Poland, the Nordic countries, the Netherlands, Belgium, France surrendered before the lightning-fast Hitlerian assault. But not Great Britain! It showed its greatness with all the brilliance that comes from the heroic act of an entire people, under the leadership of Churchill, the hero of our days. In this political atmosphere, our animosity toward the occupier grew stronger. It increased every day, and with every moment, we became more aware of our path. The feeling of threat and danger posed by the presence of strangers in our land opened our eyes even wider. Students came closer to one another, and the spirit of solidarity developed rapidly. Wherever we were, in school and on the street, in clubs and libraries, we considered it a high patriotic duty to help one another in every way and for every occasion. Although still without organized forms, we felt united, and the shared ideal was enough to gather us as constituent parts of a single body.

The aims were the same, the positions were the same: the restoration of lost independence! With the situation created, our path was clearer, and our goal had a well-defined objective. This unity of viewpoints, although general, brought us much closer. It became a rule to meet, commenting on every piece of news, explaining everything from “our perspective.” A new activity began to emerge, initially formless and not fully conscious, but later becoming more concrete and defined. This tendency decisively threw us into the fight against the occupier. A strong spirit was born, an uncontrollable opposing spirit. In our youthful hearts, the occupier had definitively lost the battle. It was our first victory! Such a stance placed us against the elements of the fascist police. The need was felt to seek and find more studied and secure forms of meetings. Group studies provided us with the best opportunity. In these gatherings, long and sincere discussions took place. A new circle was created with a unity of thought. This closeness created the first core of an organization that gradually took on its concrete form. The opportunity did not miss to show our worth.

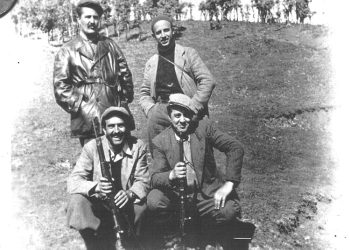

When the idea of a demonstration against the occupier was proposed for discussion, we all approved it. It was decided that two days before the demonstration, a meeting of the “most trusted” comrades would be held, where the mechanism for its development would be discussed in more detail. In the small house of a colleague, we gathered in a conspiratorial atmosphere, unknown before. The first act was the oath. This momentous occasion strengthened all of us that day and gave us courage. The homeland called us, and we responded: Yes! Our aging parents unloaded the burden of paternal responsibility onto our youthful shoulders. Exhilarated, we sang the anthem of the flag together in a low voice, which this time sounded like a sublime signal for revolt. It was the first day in my life as someone engaged in “illegal” and dangerous activities. Despite the unavoidable feeling of fear, enthusiasm seized us. I was happy!

February 1942. – The demonstration erupted, just as planned. After an impressive and noisy march, filled with shouts and slogans, the fascist police forced our column to move into the large city park. Away from the main street, they attacked. A quick and fierce clash ended with the shots of revolvers. The crowd dispersed./Memorie.al

Continues next issue