By Raimonda Moisiu

Part one

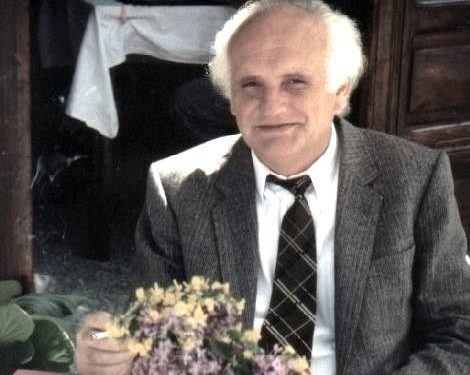

Memorie.al / Dr. Ilinden Spasse is the son of a writer, which for him means a great deal – it means being born alongside literature and the art of writing. He is the son of Sterjo Spasse, one of the most prominent Albanian writers of the 20th century and one of the most powerful bridges between the Albanian and Macedonian nations. A modern writer, Sterjo Spasse evoked peace and harmony between peoples. Both father and son are pioneers of Albanian letters, appearing as if they have stepped out of a historical museum of literature. Beyond Dr. Ilinden Spasse’s natural inclination, his inspiration for writing was drawn from life’s dreams and experiences, guided by an internal voice and a distinct individuality.

Ilinden is a prose writer with a magical power to parade a vast number of characters – both simple folk and those in power. He reveals not only their vibrant characters across the past and future but also narrates their freedom with subtle, sensitive humor and sharp artistic sarcasm. This mastery of storytelling, much like his father’s, has established him as a master of the craft. He has published numerous novels and short stories, most notably the monographic work, “My Father, Sterjo.”

In the field of translation, he brought Michael Hart’s “The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History” to the Albanian reader. In late July, I met with Dr. Ilinden Spasse, his charming wife Maria, and the writer and poet Përparim Hysi in Tirana. It was a “writers’ coffee,” where the main topics were literature and literary criticism. He gifted me his latest novel, “The Philosophers’ Pavilion.”

I particularly wanted to ask him about his father’s literary legacy and his own early creative journey. In this interview, the well-known and talented writer, Dr. Ilinden Spasse, speaks about himself and his father, the distinguished scholar Sterjo Spasse.

Ms. Moisiu: Mr. Spasse, I would like to be direct: Was literature an early interest of yours, or was it something born later as a passion and desire?

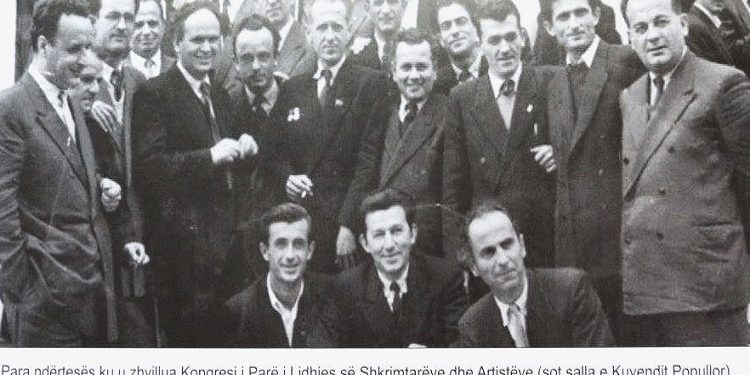

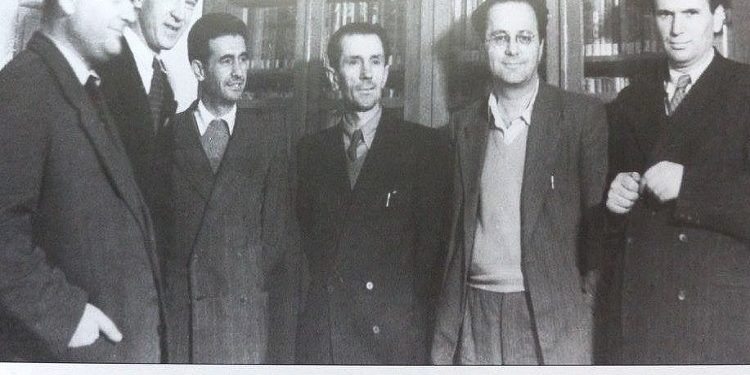

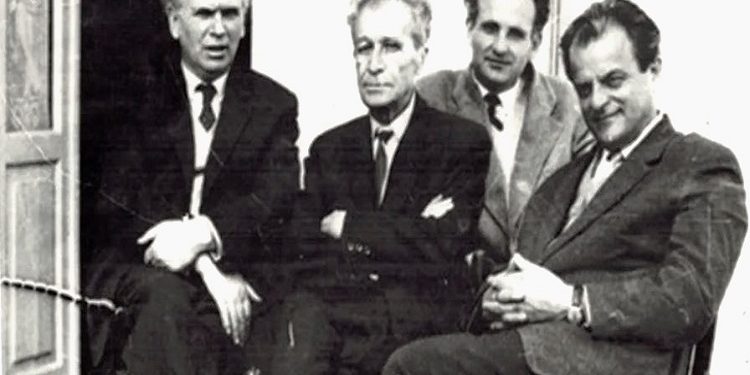

Ilinden Spasse: In fact, being the son of a writer, I must say I was born in the midst of literature. I say this because, in my early childhood, I “played” with my father’s friends. I was coddled by them; they would take me on their bicycles for rides around Tirana or take me along with their own children to the stadium to watch football matches. Most of them were full of humor, and their behavior made you love them dearly, even though I was just a child and they seemed like giants in my eyes.

They were my father’s friends, but the way they treated me made me feel as if they were my friends. It was much later that I realized they were writers. Until elementary school, I couldn’t even conceptualize the word “writer.” When I reached the seven-year school [middle school], and the literature teacher would give us a reading passage written by one of them, I – being unrestrained – would shout: “I know the author of this story!”

“This author gave me half a chocolate because the ‘wolf’ had eaten the other half; the one who wrote this other story bought me ice cream…” and so on. These authors whom I knew so well and considered my “friends” were Mitrush Kuteli, Nonda Bulka, Nexhat Hakiu, Petro Marko, Vedat Kokona, Dhimitër Shuteriqi, Shefqet Musaraj, and later Jakov Xoxa, Fatmir Gjata, Llazar Siliqi, Ismail Kadare, Dritëro Agolli, and others. I have tried to describe them in detail in my monograph, “My Father, Sterjo” (1995). So, I was born among the very founders of modern Albanian literature.

Ms. Moisiu: What is the most important thing you learned when you began to understand what life is?

Ilinden Spasse: That is a difficult question. In life, everything develops gradually. Understanding comes in stages according to age, interests, and the culture you receive from family, school, and society. In adolescence, you are more restrained, subconsciously searching for yourself. In youth, you think you “know it all” and are stronger than everyone else. It is only in maturity that you begin to analyze the events of life and hold a critical stance toward yourself.

Ms. Moisiu: Do you remember your first publication, that moment you said to yourself: “I did it! I am a writer too”?

Ilinden Spasse: Yes, I remember very well. It was the early 1960s. I had finished my lessons and went out for a walk. Suddenly, on “Kavaja” Street, I saw a girl who caught my attention. Subconsciously, I began to follow her. Suddenly, she vanished!

I looked left and right – many apartment buildings had been erected in record time. I had seen them before, but this time they made a deep impression on me, perhaps because they had “hidden” the girl I was following. Right there, I whispered to myself: “Searching for the girl…”, which became the title of my sketch.

I went home and immediately put those impressions on paper. After writing it, I felt a sense of relief I had never experienced before. Eventually, I plucked up the courage and gave it to my father to read. I waited for days, but he said nothing. I felt 100 times regretful. To me, he was an idol; why should an idol deal with my “nonsense,” especially with such a provocative title?

Then, one morning, I heard a voice from the end of the courtyard: “Congratulations, Ilo, it’s been published!” I ran out and saw Nonda [Bulka]. He was holding his “Bianchi” bicycle with one hand and waving a newspaper with the other. I was stunned. He handed me the newspaper “Zëri i Rinisë” (The Voice of Youth). There, on the front page, was the title “Searching for the Girl,” an illustration of a boy following a girl, and my name underlined below. I think my father was happier than I was in that moment, but the one most delighted was Nonda himself.

What had happened? My father, after reading it, had called Nonda to get an impartial opinion. Nonda, without telling my father, had taken it straight to the newspaper and handed it to the Editor-in-Chief, Dhimitër Verli, who was known for supporting young talent.

Ms. Moisiu: What were the essential elements that drove you to write the monograph about your father?

Ilinden Spasse: I felt the need to present my father’s figure on several levels:

- As a human being: In his relationship with my mother, who was entirely unschooled. Their harmony was extraordinary. I lived with them for 50 years and never heard them argue. My mother had a great wealth – the folk spring – which my father used beautifully in his works. Our home became a “Writers’ Club” where people came to share their troubles or consult on life problems, always met with my mother’s hospitality and my father’s wisdom.

- As a teacher: Sterjo served in education throughout Albania. He was a brilliant methodologist. He was deeply involved in the 1946 educational reform and authored textbooks that were used for decades. His early novels, “Afërdita” and “Afërdita Again in the Village,” were dedicated precisely to the emancipation of Albanian society through education, starting with the emancipation of the teacher./Memorie.al