By Bashkim Trenova

Part twenty

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the well-known journalist, publicist, translator, researcher, writer, playwright and diplomat, Bashkim Trenova, who after graduating from the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Tirana, in 1966 was appointed a journalist at Radio- Tirana in its Foreign Directorate, where he worked until 1975, when he was appointed journalist and head of the foreign editorial office of the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’, a body of the Central Committee of the ALP. In the years 1984-1990, he served as chairman of the Publishing Branch in the General Directorate of State Archives and after the first free elections in Albania, in March 1991, he was appointed to the newspaper ‘Rilindja Demokratike’, initially as deputy / editor-in-chief and then its editor-in-chief, until 1994, when he was appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with the position of Press Director and spokesperson of that ministry. In 1997, Trenova was appointed Ambassador of Albania to the Kingdom of Belgium and to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Unknown memories of Mr. Trenova, starting from the War period, his childhood, college years, professional career as a journalist and researcher at Radio Tirana, the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’ and the Central State Archive, where he served until the fall of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, a period of time when he in different circumstances met many of his colleagues, suckers of some of the ‘reactionary families’, etc., whom he described with a rare skill in a book of memoirs published in 2012, entitled ‘Enemies of the people’ and now brings them to the readers of Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

Enemies of the people

Kiço Fotiadhi, a talented voice of the Albanian Radio-Television with “stain in biography”!

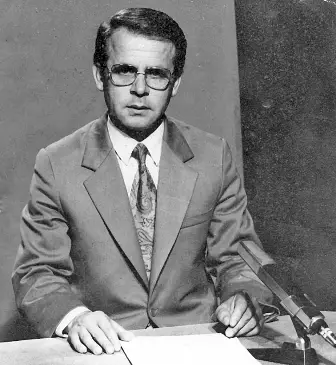

Another talented voice of the Albanian Radio Television has been Kiço Fotiadhi. Calm, smiling, optimistic, he followed the reading tradition created by Haki Bejleri and took it further. Kiço Fotiadhi was of the same generation as me. In 1966, after graduating from the Higher Institute of Arts, he was appointed keynote speaker at the Albanian Radio-Television. He started collaborating with Radio Tirana in 1959. While still a student at the Art High School, he started speaking as an external collaborator at the microphone of Radio Tirana. At that time, Albanian Radio Diffusion broadcast with reduced hours, at 06-08 in the morning, at 12.00 – 18.00 and then at 20.00-22.00 in the evening.

In 1960, the Albanian experimental television started broadcasting. Even these were quite reduced; they started with one hour of broadcasting twice a week, only for the capital, Tirana. On March 13, 1963, while studying acting at the Higher Institute of Arts, Kiço Fotiadhi gave the first news show on Albanian experimental television. “In 1963,” he says, “Stoli Beli proposes to me to give the news on television. I went and started working with the camera. I did a week of practice. The studio was a simple hall 5 x 6 meters, a simple table and a small bench. At that time, the whole of Tirana, with the exception of the ‘Bloc’ where the senior party and state leaders lived, could have had some 15-30 black and white televisions.

Over the years Kiço greatly expanded the range of his work in Radio-Television, which also increased his personality. In addition to reading the news, he also dealt with political, social, historical and cultural conversations, presenting spectacles, but also with telereporting. Kiço Fotiadhi was characterized by a sound force in the logical reading of the text and for its pure diction. He knew how to use his mother tongue in the most perfect way.

It was not even said about Kiço to continue for a long time on the Albanian Radio-Television. Political “radiologists” discovered that he also had a “stain on his biography”. An anonymous letter sent from the village, where his parents originated, stated that Kiço’s father had been a member of the Fascist Party. Members of the Fascist Party, according to an official order, were automatically at that time, all those working in the administration. This “rule” defined Kiço’s father as such. The letter further stated that: Kiço’s mother had first, second, third cousins who fled to Greece. At that time, to have a relative who fled Albania or not, but simply left, even before the Second World War, as an economic emigrant, was enough to be politically suspicious of the dictatorship. The consequences were not lacking. Thus, on July 1, 1974, Kiço was fired from Radio Television and hanged, along with his wife, a worker on a farm where he had to nail crates of cucumbers or tomatoes prepared for the market.

After two years, they take him to work for another two years in the mountainous area of Lura in northern Albania and then he returns to Tirana as director of the Palace of Culture “Ali Kelmendi”. Meanwhile, the special programs that had been made with Kiço’s voice were removed from the Radio archive and his chronicles were removed from the Television. Kiço knocked up to some of his father’s acquaintances in the Politburo, but the knocking fell on deaf ears. Only in 1980, he was able to resume cooperation with the Albanian Radio-Television. “Then my biographical restoration began”, says Kiço. Apparently, it was “clarified” that the diagnosis had been wrong, so the “stain” was not true or, at the very least, not dangerous. For all these years of stress, discrimination and denigration it was not even thought that anyone should be held accountable. Kiço himself and his family should even know in honor of the Labor Party and the dictator of his comrades, who were “objective” and took his problem to heart.

Anonymous letters to Alfon Gurash, the master of television journalism!

The list of those who left or waited to leave, in those years and then from Radio Television, are very long. It was the time of anonymous letters, slanderers, avengers and money launderers. This active army of the regime was a sword over everyone’s heads, regardless of merit at work, internship, despite the devotion you could have shown by serving the dictatorship, for one reason or another. Such a letter was sent to the General Directorate of Radio-Television also against Alfons Gurash, one of the best, most capable and talented radio reporters and tele-reporters that this institution has had, a born journalist. His dismissal was prepared because the letter claimed that Alfons’s father had been a fascist federal during the 1940s. Alfonsi’s father, Kola, as well as Kiço’s father, was in those years an honored and respected teacher. Catholic clergyman, imprisoned by popular power. Others “remembered” that he had a brother for a father who had fled to Australia, etc.

The irony is that figures such as Kiço Fotiadhi or Alfons Gurashi, the target of the major purges carried out on Albanian Radio and Television during the dictatorship, left or moved from the screen even after the overthrow of the dictatorship, after 1992. Kiço Fotiadh was fired because he had once read Enver Hoxha’s speeches at the microphone and on camera, that is, because he had faithfully served monism! After that, a new difficult period begins for Kiço, especially after the Palace of Culture Ali Kelmendi closes, where he continued to be its director. To make a living he serves as a translator for some merchants, unemployed even goes to his immigrant children in Greece. In 1997 he will return from Greece and will resume cooperation with the Albanian Television.

Alfons Gurashi was removed from the Albanian Television because he had made radio chronicles and tele chronicles from the dictator’s various visits to Albania! His portrait should no longer be present on television screens! He moved to Radio Tirana to continue working where he started his first day. On Radio Alfonsi he built a show based on which he had a direct conversation with the listeners. Here, too, the “anonymous” were not separated. One day, on the phone, someone comes up and starts “reminding” Alfons of his biography. After listening to him without interruption, Alfonsi says: “I forgot that I did not ask you. Where were you from? ” From the phone the person on the line answers: “From Kruzha”.”Very well,” adds Alfonsi. You should know that in Kruzhë there is a proverb that says: “every tribe has a dirty.” Kruzhaku did not prolong the conversation, he left the line. Sometime later, Alfonsi also left the Radio.

Unlike Kiço, whom I met on Radio Tirana, I had known Alfonsi as a child. We were both in the pioneer districts at the Ali Kelmendi Palace of Culture. I was in the choir district; Alfonsi was in the Theater district. He even recited very beautifully. He was persistent and wanted to achieve in every way what he intended. I remember how in 1956, the III Congress of the Albanian Labor Party convened. The pioneers of the Palace of Culture “Ali Kelmendi” were elected to greet this Congress. I was assigned to be in the first trio of pioneers to enter the convention hall. We rehearsed several times how we would get in and out of the hall. At the last moment, before entering, they gave me a pioneer trumpet in my hand and told me that I should give it to her as a signal that the pioneers had arrived. I did a test, but the sound did not come out as it should. Without wasting time, Alfonsi takes the trumpet from my hand; it falls to her as it should. He took his place in the top three and I moved somewhere around from the bottom.

I later met Alfonsi again at the “Red School”, at the “Çajupi” gymnasium and at the Faculty of History and Philology. He was always smiling, always ready to take part in the most unexpected jokes like that of an evening of high school years, when we were conducting military training lessons. In the field of sports of the United School “Enver Hoxha”, which was preparing officers for the Albanian army, while in the dark the military instructor was giving us the explanations of the case, Alfonsi together with another, who I do not remember, approach and then urinate on his coat?

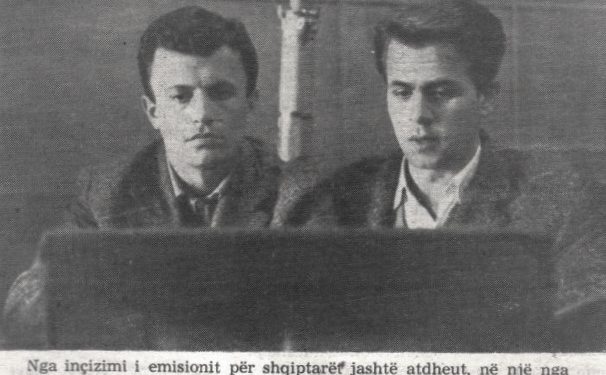

Alfonsi finished his studies a year before me and started working at Radio Tirana in 1965, a year ago by me. In the same year, Agron Çobani started working in this institution. Just as when we remember the speakers of the news show and we cannot mention Haki Bejler, without remembering Vera Zheji or vice versa, even when we talk about the chroniclers of the time, we cannot talk about Alfonsi, without remembering Agron or vice versa. Both of them gave a noticeable boost to the radio chronicle covering the political, economic and social problems in the Information Office. Thanks to them, you can say without error, the school of Albanian radio chronicle was created.

In more than 30 years of work in the Albanian Radio-Television, Alfonsi realized, always successfully, countless chronicles, interviews, reports. It was he, Alfonsi, who first started to include in his chronicles the student movement against the regime; it was he who again screened the fall of the statue of Enver Hoxha, who announced the creation of the first opposition party, the Democratic Party.

My first collaboration with Alfons Gurashi, who was not a communist!

I have only had one small “collaboration” with him as a radio chronicler. Alfonsi had recorded a conversation with an agricultural cooperative chairman. As the broadcast time approached, at the time of editing in the studio, he realized that the recording was damaged, it was technically non-transmissible. He calls me and asks me to do the role of chairman of the cooperative. I accepted. He asked me some questions and I answered them as Alphonse told me. In the end I asked him not to create any problems as the chairman would understand that it was not his voice. Alfonsi assured me that, in such a case, he would explain to the chairman that in the microphone the voice underwent the same change, so he was not faithful to the original! However, Alfonsi told me, the mayor will be happy to appear on a news program on Radio Tirana.

Alfonsi was not a communist; he had nothing in common with communism and its tyranny, behind the scenes or intrigues. After his sudden death, no voice was heard; no line was written that would accuse him of being an obedient servant of the dictatorship, of being a journalist of the dictator’s cult or of a flatterer of power. On the contrary, he was described as the “king” of the chronicle, as the “icon” of journalism. The Albanian Prime Minister himself, Mr. Sali Berisha, meant on this occasion that: “Alfonsi was an emancipated journalist with a powerful creative, journalistic, journalistic activity, but he was also a citizen, a parent, a family member, a friend, a a dear friend to all those who have known him. In this context, he leaves behind the pain of a real loss for journalism, but also as a citizen, as a man with achieved human values. In Albania, the dead are highly respected, even more than the living! In this role, the “Golden Palm” deserves, especially, the leaders of politics, who seem to be eagerly awaiting a death to reveal their entire oratory.

Alfonsi died in May 2007 at a wedding. There is no more beautiful death! Joyful as he always was in life, he died amidst joy, departed along with her.

On November 18, 2011 I received a message from Tamara Gaci, former translator of the Russian show on Radio Tirana. After reading a part of my memoirs, those related to Radio Tirana, she wrote to me: “Baçi! I read the material with curiosity and attention, but often my eyes filled with tears, which mixed with the leitmotif of a Russian song with these words: “Kak mollodi mi bili, (how young we were), Kak mollodi mi bili (how young we were), Kak verili sebja (as we believed in ourselves). It was a terribly difficult time in the spring of our lives, but thankfully it was spring. And thanks to all its powerful colors like: Youth strength, self-confidence, naivety, enthusiasm, dreams, desire to live and thrive, we survived and left behind the “Gulag” of the entire Albanian people. We also left behind our spring.

Now all the protagonists that we have left from Radio Tirana of that time are old; in adulthood, many have even been scorched from that time, scorched to the depths of the soul.

This was our destiny. Personally I have no hatred for any of my colleagues and co-workers because I know that even those red, very red ones, did not act on their wish. To say that it is a matter of character?! I often eliminated this question with one word: Children – the most sublime thing for anyone.

“After the strong waves we have left behind, I wish everyone good old age, renewal in our children and grandchildren, in a free Albania, beautiful as we have dreamed, in a European Albania.”

TRAINING FOR COMMUNISTS AND COMMUNISTS IN THE OFFICE OF CONSTRUCTION VEHICLES

It was Bardhyl Zekia, my friend and colleague in the East Editorial Office, who pushed me to apply to be accepted as a member of the Labor Party. Thus, as he told me, Kiço, Hasani, Dhori and others would not be able to speak and decide for me without my presence. I myself did not have any incentive to become a communist. I felt like that even without being a member of the Labor Party. I, on the other hand, felt more devout as a communist than enough of those who, in my opinion, were such with the card, but not with the heart, who had filled the ranks of the Party as smugglers and not as militants of a sublime ideal.

The organization of the Foreign Radio Party accepted me as a candidate for a member of the Labor Party. She decided that for three years I would work three days a week in Radio, so I would continue to work as a journalist. The other three days of the week I worked in a production center, among the working class. As a rule, the decision of the organization of the Foreign Radio Party was reviewed in the Committee of the Party of the Region, which also covered the Albanian Radio-Television. This Committee approved my candidacy.

After a few days I was told to go and start my internship as a worker in the Rruga-Ura Enterprise located on the outskirts of Tirana. I had no idea what I was going to do there. I knew that this company took care of the maintenance or asphalting of the streets of the capital. It was not about opening new roads. During almost half a century of communist rule in Albania, in Tirana, except for the inner ring of the city and a small road in what was called “New Tirana”, almost no other road was built. Thus I saw myself accompanying with a shovel a roller, which pressed the newly laid asphalt somewhere in the center or on the outskirts of Tirana, in winter or summer, as the case may be. This would be my ideological hardening, acquaintance with life, with the working class and its problems! Many slogans were then used: “The communist is a soldier of the Party”, which meant the Party, as the army and the Party discipline as the barracks discipline, ie blind obedience to the command. Blindness was thus equated with piety! It was even preferred that it be as deep as possible to ascend even higher in the ranks of piety.

On the appointed day I showed up at Rruga-Ura Enterprise to start work. There I was told that they had no vacancies in the staff, so I could not do the internship of the Party candidate in this enterprise. Consequently, the Party Committee of the Region decided that I should do an internship in the Construction Vehicle Workshop (OAN), which was very close to the Rruga-Ura Enterprise. I was a “soldier” of the Party and would go where the Party thought. I could be a co-operative, a sweeper, or a caretaker of a horse stable, nothing of this nature was out of the question.

At the Construction Vehicles Workshop I first met its director, Agim Hysa, a short, very dynamic man, with a quick and open speech. During the three years that I stayed at OAN and thereafter, I cherish the best memory of Him He enjoyed the respect of the Office workers. I met by chance in Brussels, 35 years after I left the Office, a former head of her ward, Lutfi Dashi. He had come to visit his son. I asked him, among other things, about Agim Hysa. Lutfiu told me that he was dead. Construction Vehicle Workshop workers had raised the necessary funds from their savings and erected a bust of him in the workshop yard. I do not believe that there can be any other similar case, at least in Albania.

At OAN I started working in the battery department. In this department, broken vehicle batteries were collected, lead parts were removed from their boxes and melted in an improvised oven to be poured into the previous form and put back into use. There were five people working in this ward, Milto Mima as the person in charge, Haxhi Kulla, Liria, Lulja and another woman who called her “the bride”. Milton and I became friends very quickly. He was the brother-in-law of Robert Schwartz, with whom I had worked for years on Radio Tirana. His sister, Aristeja, was married to Schwarz. Even our first conversations were about Robert Schwartz.

Working in the drum department was not difficult, but the risk was great. The lead smelting furnace was almost open. Lead vapor from its boiler circulated freely in the ward space and “saturated” the lungs and blood of its workers and beyond. Everyone was aware of the risk, but they could not avoid it, because the work in this ward was paid somewhat better than in other wards. Health protection measures were zero, if we exclude one or two glasses of extremely skimmed milk per person every day, a mandatory annual blood test and a dock workwear once a year or two, I’m not sure.

How I lied to the director of OAN, about the worker who took the milk home!

At the drummers I saw how the workers did not drink the milk given to them for the work they did, but kept it to be smuggled home, to feed their children. It once happened to me that I was stuck at the entrance of the Office, as if to say the same controller or responsibility for the entry and exit of vehicles and people in the Office. Shortly before finishing work, the director, Agim Hysa, approached me and told me that during the departure of the workers, I would stop Haxhi Kulla, whom I would accompany to a small cabin, which served as an “office” or post office. . He had signals that Haxhiu did not drink the milk, but sent it home. I stopped Haxhiu at the entrance and escorted him to the cabin. The director, Agim Hysa, was waiting there. He showed me a small container, which Haxhiu was holding in his hand. “Check it out,” he told me. I opened the container, shook it a few times left and right and finally said: “Nothing, it is empty!” Haxhiu left calmly, but quite grateful to me.

Actually I lied. The container had one or two glasses of milk at the end, which milk only had its name because it was more water than milk. With a conscience as a communist I could not be at peace. With conscience as a man it was different. If I had told the truth, Haxhiu would have been convicted. I cannot say exactly what measure could be taken against him, but even dismissal as a “thief” was not excluded. In his biography, this “label” would never be shared. For so many others had even tried prison. Of course, all these excuses did not come to my mind immediately. I said “the container is empty” because that’s how I felt it should be said. I did not want Haxhi Kulla, an excellent worker, who spent a good part of his life unprotected between lead vapor and battery acid, to be punished because he thought more about the children than about himself, about his health.

In the Construction Vehicle Workshop I saw that the “care” of mother Party for the working class, which was trumpeted as a class, which inseparably holds power throughout the country and in its entire links, was almost zero! Thanks to this “care” the workers of the battery department did not stop being hospitalized for blood poisoning one after another for years. I asked Lutfi Dashi about them when I met him in Brussels. He told me that Haxhiu was dead, as well as the “bride” and Liria, for Lulen he did not know if he was alive or not. None of them was old enough to say “goodbye” to life, children, and families. They were not shot as enemies of popular power; they were not shot in the head or in the heart by the shooting squad. Their hearts stopped beating because the vapors of the lead poisoned her blood. The “enemies of power,” as his opponents were called, and the “pride of power,” as the working class called them, were united, not infrequently, by the same tragic fate, death by bullet. Memorie.al

The next issue follows