By Bashkim Trenova

Part fifteen

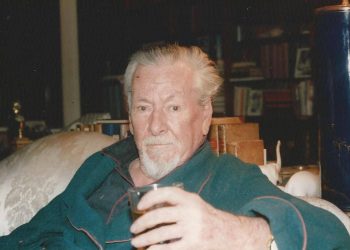

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the well-known journalist, publicist, translator, researcher, writer, playwright and diplomat, Bashkim Trenova, who after graduating from the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Tirana, in 1966 was appointed a journalist at Radio- Tirana in its Foreign Directorate, where he worked until 1975, when he was appointed as a journalist and head of the foreign editorial office of the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’, a body of the Central Committee of the ALP. In the years 1984-1990, he served as chairman of the Publishing Branch in the General Directorate of State Archives and after the first free elections in Albania, in March 1991, he was appointed to the newspaper ‘Rilindja Demokratike’, initially as deputy / editor-in-chief and then its editor-in-chief, until 1994, when he was appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. with the position of Press Director and spokesperson of that ministry. In 1997, Trenova was appointed Ambassador of Albania to the Kingdom of Belgium and to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Unknown memories of Mr. Trenova, starting from the war period, his childhood, college years, professional career as a journalist and researcher at Radio Tirana, the newspaper ‘People’s Voice’ and the Central State Archive, where he served until the fall of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, a period of time when he in different circumstances became acquainted with some of the ‘reactionary families’ and their sucklings, whom he described with a rare skill in a book of memoirs published in 2012, entitled’ Enemies of the people ‘and now brings them to the readers of Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

“Enemies of the people”

Foreign women who started working as translators at Radio Tirana

A large number of translators also worked at Foreign Radio. When Alberti and Dervishi and I started working, in August 1966, Radio Tirana broadcast only one show a day in English, French, Russian, Italian, Serbian and Greek. Later, over the years, broadcasts in other languages were added, without excluding Indonesian, Iranian or even Chinese. Our dictator, the leader of the Labor Party, Enver Hoxha, had taken on the burden of leading the proletarian and liberation revolution everywhere in the world!

His megalomania was boundless. He was convinced that his word and thought would set the world proletariat on its feet to overthrow capitalism, as well as the oppressed peoples to break the shackles of slavery! The mission of Foreign Radio was to broadcast this word, this thought, everywhere in the world. When we started work, our office was completely free, we were the first to settle there. Afterwards, the Foreign Directorate would occupy the entire space of the IV floor of the Albanian Radio-Television and a part of the third floor. Its broadcasts would reach 24 foreign languages, in more than 80 hours of programming per day.

Thus, the number of translators on Radio Tirana increased continuously. Especially, the number of Russian, Polish, Czech, Hungarian, Romanian, Bulgarian, Serbian women married to Albanian men, who were recruited as translators on Foreign Radio, increased. Each show had two to three translators, usually translating political articles and comments written by Foreign Radio editors. Many of them were also speakers of the materials they were translating. They did not read into the open microphone, i.e. connected directly to the listeners. The materials were first recorded on magnetic tape and then transmitted from studios guarded by service police. The entrance to these studios was strictly controlled.

We editors had a close relationship with translators. They often came to our offices to ask us questions or to clarify a word or an opinion expressed by us in a political commentary, which they had to translate. They knew full well that even an incorrectly translated word could cause unthinkable problems for them and their families. In fact, they could not avoid these problems, no matter how correct they were in office or in general in relations with the Albanian state.

Friendship with the Russian, Tamara, the wife of the famous composer who refused to leave him!

The first translator I knew on Radio Tirana was Tamara Gaci. It really wasn’t an acquaintance, but just a distance look into the lobby of the Radio. It was my first day on the Radio. I was waiting for someone to come and accompany me to the Foreign Directorate of Radio, where I would also work. While waiting I see a petite, delicate and beautiful woman pass by like a Barbie. She was going to have a coffee. I later learned that her name was Tamara Gaci, a Russian translator. Then we would become good friends and remain so over the years. She would not call me by my full name, but by an abbreviation of it, like all my childhood friends and acquaintances, simply Baçi. I would occasionally bring her, as well as all the other translators, a rose, which I plucked from my garden and placed on their typewriter in their absence. They started working later than us editors.

Tamara Kudrickaia (Gaci) is of Russian origin, Muscovite. There in Moscow she fell in love with Pjetër Gaci, an Albanian student at the conservatory “P. I. Tchaikovsky ”of Moscow. It was she who took the initiative to meet Peter, whom she had attended as a spectator at a series of his concerts in the conservatory hall.

In November 1957 Tamara, a student at the Faculty of Mechanized Accounting, interrupts her studies and decides to go after great love. She marries Pjetër Gaci and they come to Albania together. Of course, neither Peter nor Tamar could have imagined the years of horror that would follow and test this love.

In 1961 the Soviet Union severed diplomatic relations with Albania. Tamara decided to stay in Albania. Speaking about that time, she says: “We were living in Tirana. The situation was such that both sides were feeling it on the skin. Even Peter that year, surprisingly was taken into the army. He had both parents and me. He felt extremely bad. Then I said to me, “Friend in misfortune is not left.” Peter left me free to decide. And I decided. Peter has been in a moment of family crisis: two elderly parents, me on the verge of breaking up the family and the one recruiting soldier. “Understand for yourself.”

After this decision begins a life in the shadows for Tamara, a life without fear for fear of breaking up the family. She, like all other foreign women married to Albanians who decided to stay in Albania, lost their nationality. She burned part of her library brought from Moscow that might have seemed suspicious of the regime in Albania. At the time for this regime the Russian woman was seen as an element recruited by the KGB. Along with the “shadow” books, Tamara also burned her art block. She wrote poetry. “It seemed to me that I had made a crematorium for half of my being,” she said years later, in an interview.

This “crematorium” would not save Tamara from endless troubles throughout her life. The other half of her being was still unburned. The regime “took care” of this. Tamara was more than aware of this “care.” She did her best to save her.

Russian women fear translation, after Myfit Mushi complained to the director!

I remember how Valia Çollaku, the irreplaceable speaker of Radio Tirana for the Russian show, was sometimes angry with Tamara’s translations. Valia, also Russian, wondered how a Russian like Tamara could translate in her native language, while Enver Leka, an Albanian translator for the Russian show, was more Russian than she was in his translations. In fact, Tamara translated from Albanian into Albanian with Russian words. She tried to respect the Albanian text in detail. He did this for fear that one day he would be held accountable, that he had deliberately changed the Albanian text, because he had evil thoughts in his head, that this was how he served the KGB, or that this was how he wanted to sabotage the Russian show on Radio Tirana. All of these scenarios were entirely possible and practiced at the time. Apart from Valias, Mufit Mushi, the one who watched or controlled the recording of the Russian show in the studio, a Russian maniac, was not always happy with Tamara’s translations. He too was constantly remarking.

One day the Mufti also goes to Kiço Pandeli, the director of the Foreign Radio, and complains to him that Tamara had not correctly quoted Lenin in a translation. Kiço Pandeli called Tamara “caught” in guilt. She, careful as always, had not translated Lenin’s quote from Albanian into Russian, but had found Lenin’s works in Russian in the Radio Library, and from there she had extracted Lenin’s quote from the original. She escaped the danger this time too, but the danger, however, was always near her.

Tamara Gaci refused to testify against her Russian friends, who were arrested!

Tamara was summoned to testify in a court case against her compatriots. To refuse to be put in the service of the dictatorship meant, according to its logic, to be against. She refused to testify. The consequences were not long in coming.

At the moment when her compatriots were being imprisoned, friends of Peter’s many benefactors said to the latter: “Take him to Shkodra because there is a danger that his wife will be arrested”! So they left Tirana, if I am not mistaken, in 1975. In Shkodra Tamara was locked in her sister-in-law’s house. Peter justified this closure by saying: “the woman is very sick.” “Of course we were scared,” Tamara will confess, “because my friends went to jail.” In Shkodra she lived for some time alone, without Peter. This was sent to Elbasan, a city in central Albania, and then to Vlora, in the south of the country. The dictator raised to the pedestal Peter’s anthem “For you Homeland”, but not for its indisputable values. He was “longing”, almost crying when he heard the sound of this song.

Television chronicles and documentaries dedicated to him were often accompanied by this song. The dictator needed Peter’s hymn to glorify him, to identify his person with the Homeland. Meanwhile, he would not hesitate for a moment, to shake Peter’s family, to throw part of it to the north and the rest to the south, to keep it under the constant tension of the crushing, final destruction. Fortunately, Peter, being one of the most prominent Albanian composers of the time, a very charming man, had his many admirers everywhere. They were close to him and Tamara again and made it possible for him to be transferred to Shkodra.

In this generally friendly city, Tamara isolated herself. When he was crossing the city streets and could accidentally find himself in front of a friend, he would change the sidewalk, cross to the other side. “One day,” says Tamara in the above-mentioned interview, “one of these friends, when he saw that I had crossed over to the other side, came forward, opened his arms and said, ‘You have nowhere to go.’ What do you have, why do you not want to meet us, why do you change our path? “Tears came to me,” said Tamara, “and I said, ‘I will change the path of those whom I love most.’ Do not take me by the neck with me. “She wanted to be like the hated character in Graham Green’s “The Invisible Man,” to have a hat like that of this character, so as not to stand out, to become invisible.

My last meeting with Tamara in Shkodra!

I last met Tamara and Peter together in the summer of 1994. I went to Shkodra with my wife Desin and a Greek, Jorgo Jorgiu, whom I had met by chance on one of my trips to Athens. I wanted to show him Rozafa Castle, an ancient castle that dominates the city and its surroundings. After lunch at the castle we left for Shkodra. I wanted to meet Tamar and Peter. This year Tamara was no longer the invisible one with hats, she was not even like that for several years. I did not know the address of her home in Shkodra, but it was enough for me to ask a random citizen on the street to find out. To be more precise, the citizen of Shkodra got in the car with us and accompanied us to the very modest house or apartment where the Gaci couple lived.

Tamara had become known in Shkodra for her dedication and enthusiasm in the early days of the Democratic Movement. She became a member of the Democratic Party since its inception. She was one of the initiators of democratic processes in Shkodra. He rejoiced when he opened the door of the apartment and saw me. We talked as old friends and as engaged in the Democratic Movement. Tamara told me how, when she saw me on TV in the activities that took place in the years 1990-1992 against the dictatorship, she went in front of the screen and made the cross praying to God to protect me. “Save God Baçi”, she had said, while Peter laughed at him then, adding that “Baçi is not a Christian, but a Muslim, so your cross cannot help him”. During our stay in their apartment, Peter sat down at the piano and played a composition of his own, a song that quickly became popular and was sung and continues to be sung as such. It was a song about love. Peter, always with humor, told us that Tamara thinks that this song I have dedicated to her!

In August 2011, together with my wife, our immigrant friend Luan Musarain and our two Belgian friends, Anne Gancberg and Mark Van den Dries, we made a trip to Shkodra. I could not be in Shkodra and not meet Tamara. So, I knocked on her door again after seventeen years and it would be again that would open it. He filled me with kisses and words of longing pronounced in the Shkodra dialect with a Russian accent. This time Peter was absent from our meeting. Two large photos of him occupy almost half the face of the wall of the waiting room.

Tamara, now 75, continued to be lively. She recited a poem from her recently published poetic volume. Then he gave me a CD album with pieces composed by Pjetër Gaci. “When you come again,” Tamara told me, “here you have the room I have for friends.” During the conversation we also planned a joint trip to Moscow with my wife and our Belgian friends. We parted with the promise to meet again, this time in Brussels.

Tamara Gaci is currently the president of the association “Dimension Human”, which she founded. In the focus of the work of this association is the most vulnerable layer of society: lonely old people, women without support. The logo of this association symbolizes a heart and the earthly globe, where the heart has the largest dimensions, just like the heart of Tamara herself. She has published a book entitled “Impressions and Memories”. An article published in the Albanian press on Tamara Gaci, among others, reads: “Although for many years on the shoulder, Tamara has the graces of a beautiful woman with an innate intelligence, of an intellectual woman who tries to emancipate society, part of which she is herself”. This “unfortunate woman but good to the point of pain, a worthy representative of the great Russian spirit”, as Tamara, my old friend Enver Muça, will portray, this lady woman with a big heart and a small body like a Mother Tereza ”, as another old friend of mine, Albert Shala, will write to me one day about it, now lives with his son, Dritan. “Here I have people I love and they love me,” says Tamara. I experience the fates of this land, this country. “Here is my husband’s grave, this is my son.”

Russian women and generally foreign women who did not leave Albania, would follow a fate like that of Tamara or even more tragic. One of these was Inga Tarasova. I knew him as a child. She lived on “Hoxha Tahsim” street, near our alley. I “met” her at the Faculty of History and Philology, where she was a lecturer in Russian, while I was a student of History-Geography. Then we would get to know each other and work together for several years on Radio Tirana, where they brought her as a translator for the Russian show. I have always been attracted to her charm, the calm and dignified way of behaving, which we, I do not know why, saw as aristocratic, imposing. I never saw him explode, get angry, protest. She did not talk much; she was reserved, maybe shy! He even laughed as if scared. We also made some jokes together. She and Tamara wanted to throw me some romes, no bad, just for humor, amicably. Tamara’s refrain was my “velvety soft” eyes.

The other Radio colleague, the Russian, Inga Tarasova Dyrzi, who was imprisoned!

Inga, whom we on the Radio called Ina, did not forget to add that if I had been in Moscow, the girls would have hung around my neck and said, “We are your victims.” We laughed together as good colleagues and friends without knowing and without thinking, at least to me, what fate had in store for us, the next day!

Inga came from Moscow following her beloved and lived in a simple Tirana family, respecting the traditions and culture of the country. She left Russia at the age of 24. There he fell in love with Seit Dyrzi, at that time an Albanian student in Moscow, then, in Albania, chief engineer and Laureate of the Republic Award, a hydropower designer. In Tirana, even though she missed her homeland, she did not feel lonely. Tirana and the people of Tirana are known for their special hospitality as well as for the feeling of tolerance and coexistence with others. I remember from my childhood that Tirana was a city without keys. In this environment, the small house of Seit and Inga, quickly turned into a small and cheerful nursery where people of art and culture, composers and writers came to talk and stay. Meanwhile, the fruits of love did not fail to arrive fairly quickly. Inga and Saiti gave birth to a son, Valerin, and a daughter, Diana.

Igna sentenced to 8 years in political prison and her son, Valeri, to 13 years!

The wave of persecution of Russian women coming to Albania also hit Inga Tarasova. In 1976 he was arrested. After many investigations, pressures and sleepless nights, he was finally sentenced to 8 years in prison on the false charge of “espionage”. She was sentenced on October 4, 1977, simply because she was Russian, or as Tamara Gaci puts it, “for nothing, for going out a little too much of a personality”. It was this manifestation of personality that the dictatorship could not tolerate, let alone a Russian.

As Inga Tarasova herself told years later, that night they went and arrested her at home, she was alone with her 13-year-old daughter. Her husband, Seiti, worked at the Metallurgical Plant in Elbasan, while Valeri, after not being given the right to pursue higher studies, was called to perform military service. Djana, Tarasova says, was very scared, but I told her: “Do not trust anything you will hear about us. I’ll be back. “You go to your aunt.” It would be his aunt who would keep him and raise him for six years, as long as Inga’s sentence lasted. Indeed, to be more precise, as a neighbor of Tarasova, a peer and friend of her daughter, told me, since Djana was left alone at home, Llukani, a man with one hand, may have lost the other in the war. , took him to his house. Llukan’s daughter was a friend of Djana. I do not know how long Djana lived there! She then went to her aunt, Seit’s sister.

To save her husband and children from the consequences that would await them after her arrest and imprisonment, Inga and Seiti agreed to separate, no matter how long the separation lasted. The regime would not be content with that. His revenge would further punish these “insurgents”, citizens of different states, who dared to commit the only crime, to love each other and to love their children.

The punishment of those who thought they had replaced the gods of all time knew no bounds. Valerie’s future was marked. He, after not being allowed to continue his studies, was forced to work as a porter. When he was only 22 years old, he had to face the dock, with false witnesses and then with the prison cell, where he spent his youth. Valeri Dyrzi-Tarasov was arrested in January 1979, “for agitation and propaganda and for attempting to escape. “Agitation and propaganda was called an English magazine, if I am not mistaken, where it talked about the dictator, etc., leaders of the communist dome in Albania. This magazine was given to him by a friend of his, Sokol Ngjela. Valeri had only talked about the magazine with Ardian Klosi, a mutual friend of his and Sokol. The result was the arrest of Sokol and Valeri and, coincidentally or not, a trip to Austria for specialization for Ardian Klosi. Valeri later asked Ardian Klosi if he was the one who had reported him to the State Security. Ardiani has denied.

Valeri was sentenced to 13 years in prison. Top 10 of them in the prisons of Ballsh, Zejmen, Gërmenj, Qafë-Bar and Spaç, where many intellectuals and opponents of the dictatorship have passed their ‘Golgotha’. There were some of them who had studied in Moscow, the Sorbonne, and Bologna. He was released from prison on October 20, 1988./Memorie.al

The next issue follows