By Alda Bardhyli

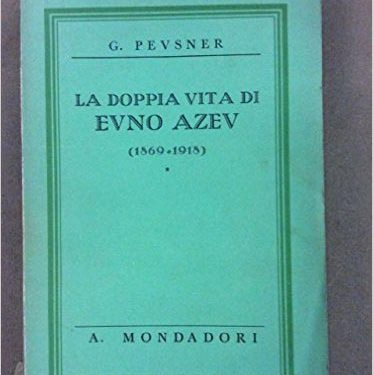

Memorie.al / The story of Yevno Azef, the Russian journalist and revolutionary, known for his engagements in the early 1900s, continues to be one of the most widely read stories in the history of espionage. Azef, known as a double agent and provocateur, would attract the attention of many writers of the time. G. Pevsner, would research his life to bring it into a book entitled; “The Double Life of Yevno Azef”, which was early translated into many languages. Azef spent the last years of his life in Germany, where he invested the money earned as an agent, and lived his last love with a German singer, Ned. In the years 1915-1917, during the First World War, he was exiled from Germany, as a foreign enemy, serving his sentence in prison.

After his conviction, he lived in Berlin until he died in 1918 of kidney disease. His grave is in Wilmersdord Cemetery, unmarked. But the life of Azef, a man to whom Russia entrusted major commitments during and before the First World War, is a way to penetrate the time and politics of the former Soviet Union, and to see the relations with the countries where it had interests. G. Pevsner’s book about Azef’s life in Italian circulated in Albania at the beginning of communism. A manuscript, with a cherry cover, that has easily survived time, brings us another story of this book, in the Albanian language.

The manuscript for more than half a century (57 years), has been carefully hidden in the library of Shefki Njuma, an autochthonous citizen of Tirana with a passion for books, who preserved it with the care of a man who knows the language of the book. The manuscript has as its translator, Ndoc Naraçin, a well-known character of the time, especially for his contributions, during the Kingdom of Zogu, holding a number of positions, who, like Azef, had studied engineering. Naraçi was in the years 1933-1944 (with two small interruptions) the director of Post and Telegraph of Albania. He was Minister of World Affairs in 1935-1936 and for one month in 1943.

With the advent of communism in Albania, he would be sentenced by the Special Court of 1945, first to death and then to 30 years in prison, but he would be released from prison in 1958. After this year, he would live in the city of Shkodra, in very difficult conditions. He must have done the translation of Yevno Azef’s book while he was in prison.

It is well known the use that the communist regime of Enver Hoxha and his successor, Ramiz Alia, made of intellectuals who were serving sentences in camps and political prisons, for the translation of a series of works from foreign literature, but also works or manuscripts, which that regime might need them. One of them must have been the book on Azef’s life, which, due to the always troubled relations between Albania and the former Soviet Union, had no chance of being published at that time.

The story that Shefki Njuma tells about how he found this manuscript, shows that this translation must have been an order to be read, by high-ranking characters or officials of the State Security and the senior leadership of the ALP, who should have more knowledge about Russia. Njuma was only 17 years old, sometime in 1959-1960, when playing in the yard of the house of Major General Halim Xhelos, (former head of the Directorate of Internal Affairs of Tirana), with his son Vladimir, to point out a manuscript, which had been sitting somewhere in a corner of the yard for several days. The boy, given early to reading, would immediately feel that he was dealing with an unusual book, from the multitude of books that were published at that time.

“I browsed the manuscript and it seemed to me a rare book for the time, and I took it to keep at home”, says Njuma. On the first page of the manuscript was written; “order for colonel Halim Xhelon”, which shows that the translation was made during the time when Naracaj was in prison. Until the 90s, this manuscript was carefully hidden, somewhere in the library of the Njuma family, to be browsed from time to time by Shefkiu, who would often “travel” into the life of one of the most famous characters. known Russian espionage. But beyond the life of Azef, the book is also a lecture on the revolution and many characters of the time. In order to have the manuscript more safely, he would tear the first page where the name of General Halim Xhelos was written.

“I tore out the first page, because having this manuscript, considering the time, made you afraid. But I didn’t give it to the man to read,” he says. After the 90s, he gave the manuscript to friends to read, with whom he often shares book conversations. The book must have been translated sometime in 1945, because until 1944, Naraçi was not known as a translator, but as one of the good engineers of the time. But the culture of its formation makes the translation have a language and a pure Albanian.

The book begins with the Russian revolutionary movement, from 1825 to 1894. “Writers who have dealt directly or indirectly with this argument have not hesitated to underline the special and extraordinary character of Russian terrorism. All, or almost all revolutionary movements, in any country, end fatally in terrorist acts, especially in moments of great tension”, writes G. Pevsner.

But according to him, in most cases, we are dealing with sporadic episodes caused by the personal initiative of people or, autonomous fanatical groups of violence, which have nothing to do with revolutionary organizations, engaged in war and often not even they know each other well. “But in Russia, for more than a quarter of a century, we can see the terrible phenomenon of terror used on a large scale, as the simplest and most direct means of political struggle and persistently applied, according to a logic cold and brutal.

For nearly 30 years, in more or less long periods, the tsarist police had to be measured for resourcefulness and courage, with terrorist groups organized on a sound basis, widely equipped, with the right tools, directed by methodical and decided, who present the figure of the revolutionary as defined by one of them, Nachaev, whom Dostoevsky skillfully painted in his romance; “Demons”, under the name of Pjetër Verkovenski”, writes G. Pevsner.

To arrive at the narrative of Yevno Azef’s life, he seeks to explain the revolutionary movement, philosophizing what a revolutionary is essentially. “The revolutionary is a man condemned in advance. He should have neither personal ties, nor things, nor loved ones, and he should also renounce his own name. He must concentrate entirely on a single passion, the revolution. His studies should be devoted only to those sciences that can serve him for his work, but above all, he should learn to know people, to rule them, to use them for the benefit of the revolution. , their weaknesses and secrets, without scruples and without mercy”, writes Pevsner.

In fact, this was the scaffold on which Azef’s life would be stretched. He should have only one goal, the revolution, and live the life of a revolutionary, stripped of the feelings and addictions of an ordinary man. While talking about the revolutionaries of the 1870-1880 period, he says that; they could not accept Nechaev’s ideas without disgust.

He takes the case of the student Ivanov’s murder, saying it was more of a personal vendetta; rather than the punishment of a traitor (it was said, among other things, that Ivanov had been eliminated because he had shown any doubts about the existence of the famous Central Committee, and cast a shadow of doubt on Nechaev’s moral character). Referring to historians, he says that they have agreed to consider the romantic and aristocratic conspiracy of the Decembrists (1816-1825) as the beginning of this movement.

When he uses the name “romantic”, he refers rather to the external inducements by which the conspirators unconsciously obeyed some of their positions and above all to the incompetence shown by them at the moment of action, than to their political ideas. . These were among the most radical, starting from the desire to suppress tsarist absolutism, or to soften it by imposing a parliamentary regime of the English type, the Decembrists, in the work of one of them, Colonel Pestel, the most intelligent man of the era his, according to Pushkin, about whom the opponents said that it was useless to argue with him, because he was always right…! Interesting in the book is the period that Azev spent in Germany. The start of the war between Germany and Russia would bring an unpleasant surprise to Azev as well.

He had invested all his capital in Russian stocks. The declaration of war also marked his financial capitulation. But Azevi was not a man who gave up easily. With the money he was able to save and from the sale he made of some ornaments, which he had forgiven his girlfriend, he opened a corset atelier, to which he devoted himself with all his patience and soul, the initiative that the adventurous life and complicated had inspired him. At first, the store did very well. The heaviest blow would come to him on June 12, 1915. In the evening of the previous day, in a cafe in Friedrichstrasen, he had met an official of the secret police, who knew his real name and had seen him.

Azevi had returned home very shocked and full of dark premonitions about the consequences that could come from this coincidence. “He has known me, the case will end badly”, he said to his friend when he entered the house. He had spent the night arranging papers and disappearing countless papers and documents. It was wartime, the Germans were no joke and he knew it.

His fear was immediately confirmed. The next morning, as he was leaving the subway station, a stranger approached him and introduced himself as an agent of the secret police. After exchanging a few words, Azev had to go with him. After being questioned for the first time and briefly by the police, he was taken to Moabite prison and locked in an isolated, damp and dark dungeon.

Why had he been arrested? He couldn’t explain it and no one would tell him. The only thing he understood was that he would not be released. After a series of adventures in prison, the only concern in this part of his life was Ned, his German girlfriend. After his imprisonment she is forced to sell all the ornaments, as the struggle for survival was fierce. He wrote dozens of letters to her, wanting to ease her absence with words. “I have had the greatest misfortune that can befall an innocent man”, he wrote in a letter.

“My misfortune finds no comparison, except with that of Captain Draifus.” And in another letter he writes to her: “Of all the people, you are the only person who stands close to me, so close that I don’t feel any separation between us. Where you are, I am also there and here are not empty words”. “You are my girlfriend”, he says in another letter, “you are the only person who is interested in me, all around me is a desert. You can imagine how much it hurts me. God must give me the strength to help.”

According to G. Pevsner, Azev has never believed in God, but now that disaster has struck him, he prays for himself and his girlfriend. “Your tears tear my heart”, he writes in a sad moment. “I can’t see your tears. Don’t be sad for me. With God’s help, everything will endure. Enough for you to be fine. I pray to God only for you. I am saddened by the fact that you suffer so much for me, because of this, your nerves are destroyed. Oh my love, you don’t have to worry about me. God will give me the strength to withstand all adversity. Enough for you to be calm and healthy”.

The events of the last years of his life are extremely felt. How a man who was bent on revolution now worries about a woman’s fragile heart. “After my prayer,” he says in another letter, “my soul is always satisfied and strong.” Sometimes even suffering makes him stronger.

But even in suffering man finds happiness, contact with God”. The advice he gives her is interesting…; “Speak only of what is necessary. Remember that others rely on you, but never rely on others. Save money, neither more nor less than it deserves; these are a good servant, but a bad master. Don’t despise people, don’t hate them. Pray for death every morning and every evening…”!

He would be released from prison on Christmas Eve 1917. Following the revolution and the peace of Brest-Litovsk, the Russian and German prisoners had to be exchanged, for this reason he was released. The old Russia had collapsed. Kerensky’s short-lived government, in which several social revolutionaries had held important positions, was soon over. The Russian Revolution developed rapidly. In front of the prison gate, Ned was waiting for him. But the long prison had ruined his health and hardened his character. At his friend’s house, he began to take revenge against the Germans, who had unjustly imprisoned him for a long time.

Fearing that he might be sent to Russia, he thought it would be more reasonable to leave Germany and settle in Switzerland. But Germany was still at war with the Entente powers and the passage to Swiss soil was not allowed. He had to submit to fate and stay in Berlin, where the struggle for living became more and more fierce. But the disease would not let him hope for long, as on April 24, 1918, he would close his eyes at the age of 49. His friend, Nedi, would give him a grand funeral, accompanying him alone to his last residence. On his grave, there was no stone, no inscription, but only the flowers that Ned left for him.

The story of this character is the story of all those people who believe in an ideal, and put their lives in the goal of a cause. An inspiring book, written in the style of a biography, that knew how to find all the facts and details that would make Azev’s life complete. A book that was translated in the prisons of communism, by a man who, like Azev, spent part of his life in prison, and then died in exile. There are many stories that accompany the life of a book, which never seems to end with the last page, but each new page is born, after the meetings the book has with readers, or translators, that give another dimension to it.

Like the cherry blossom manuscript, which Shefki Njuma loved the most, among the hundreds of books he had in the library According to the author of the book, the fate of “some characters mentioned in this story is strange and full of often tragic adventures”. “Boris Davinkov before the war, stayed for some time in Italy, and then moved to the south of France, where he worked on his literary works and stayed throughout the war. After the collapse of the tsarist regime, he returned to Russia. He participated in the provisional government, formed by Kerensky, as governor of Petersburg, commissar of war, undersecretary of state and minister. After the Bolsheviks came to power, he fled from Petersburg and joined the ranks of the anti-Bolshevik army.

In 1918, he was sent to Paris as the head of the military mission of the new government formed in Omsk, which was immediately replaced by that of Admiral Kollchak, and took part in the ambassador’s mission, at the same time, he opened in Paris a anti-Bolshevik propaganda office. In 1921, he went to Poland where he organized new anti-Bolshevik parties, but the attempt to cross the border together with these parties failed”…! But at the core of the revolution is Azevi, a character who, as you see through the words in the manuscript yellowed by time, brings the flavor of a time which, we have yet to read properly, in the history books. Memorie.al