By Bashkim Trenova

Part fifty-four

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the well-known journalist, publicist, translator, researcher, writer, playwright and diplomat, Bashkim Trenova, who after graduating from the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Tirana, in 1966 was appointed a journalist at Radio- Tirana in its Foreign Directorate, where he worked until 1975, when he was appointed journalist and head of the foreign editorial office of the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’, a body of the Central Committee of the ALP. In the years 1984-1990, he served as chairman of the Publishing Branch in the General Directorate of State Archives and after the first free elections in Albania, in March 1991, he was appointed to the newspaper ‘Rilindja Demokratike’, initially as deputy / editor-in-chief and then its editor-in-chief, until 1994, when he was appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with the position of Press Director and spokesperson of that ministry. In 1997, Trenova was appointed Ambassador of Albania to the Kingdom of Belgium and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Unknown memories of Mr. Trenova, starting from the War period, his childhood, college years, professional career as a journalist and researcher at Radio Tirana, the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’ and the Central State Archive, where he served until the fall of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, a period of time when he in different circumstances met many of his colleagues, suckers of some of the ‘reactionary families’, etc., whom he described with a rare skill in a book of memoirs published in 2012, entitled ‘Enemies of the people’ and now brings them to the readers of Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

WITH “HEROES OF THE PEOPLE”

POLITICAL BUREAU AND THE PRESIDENCY

How did I meet the Russian Nina Alexandrova, the first wife of Dritëro Agolli!

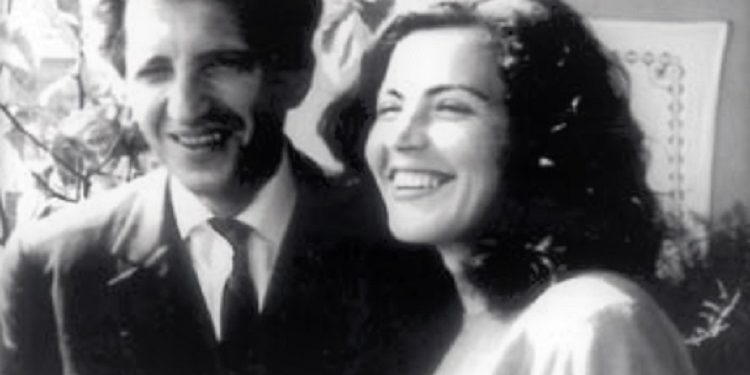

The last member of the Central Committee that I had the opportunity to meet was Dritëro Agolli. In fact, before I met her, I met Nina Alexandrova. Nina was married to Dritëro Agolli. They met in Leningrad, where Dritëroi studied at the Faculty of History and Philology for Literature. After they got married and came to Tirana, Nina was appointed a Russian teacher at the “Çajupi” gymnasium where I continued my studies. In my memories she is like the model of a teacher, incredibly diligent and aware of her task. She also paid attention to her appearance, her dress. She was quite tidy even in her toilet even though he did not add anything to her typical Russian beauty. Nina Aleksandrovna never removed a rhombus-shaped badge from her body, which proved where she graduated and in what discipline.

My impression is that she was never accustomed to the psychology of the Albanian high school student. He was always surprised by something, which made us improvise “surprises” in the series and laugh out loud. So, I remember how one day, before the lesson started, some of our friends moved all the bangs and started wiping thus raising a dust from the floor, which covered the classroom up to the ceiling. Surprised, Nina asked, “What’s going on?” One of us, cold, as if nothing had happened, replies that “we are cleaning the classroom”, so that she could find a clean environment. Nina ran away angry with us and did not conduct that lesson. I went and met him in the school hallways. It was hard for me that in class we had behaved this way with her, with a stranger, with what she just wanted to do her homework.

It seemed to me that our behavior, unlike what we had learned and heard about Albanian hospitality, only embarrassed us all. After all, I was sorry to see him so sad, alone in our upstairs hallway. I apologized for what we had done. I do not know if he listened to me, if he understood that I was sincere in my words. I apologized even though no one had charged me to do so, even though I myself had not even participated in that “cleansing” of the class. , but nevertheless, I had been present. She continued to be always angry. “You are all the same,” Alexandrova told me, pronouncing my name, which she never learned to pronounce correctly. He always called me “Trinova”, instead of Trenova. Maybe “Trinova” went better in Russian!

Dritëro Agolli’s Russian wife was forced to leave Albania with her 7-year-old son!

Nina Aleksandrova fled Albania with her son, Arian, when he was only 7 years old. I cannot say that he did well to leave and that he would not have done well to stay in Albania. This is in her consciousness and no one has to judge her. After almost 40 years, Dritëro Agolli, one of the most famous Albanian poets and novelists, returned once again to Russia where he met and hugged his son, a man, married, with family. From Albanian he had in mind only two expressions: “I will go home” and “Goodbye”; the tragedy of separation as well as the hope of meeting again one day. In a report, which was published in the Albanian press on this occasion, Nina Aleksandrova is not even mentioned! The author, director Esat Ibro, addresses her only as “Dritëroit’s first wife”. Even Dritëroi himself does not mention her name when talking about his first marriage as a “youth mistake”!

“There, with that naivete of ours,” Dritëroi said in an interview, “I knew a girl and even with remorse, like that, but I married her. It was this side, the attempt to make a family. But there I was wrong about this”! I feel sorry for both the director Esat Ibro and Dritërona. However, Nina Aleksandrovna, is the mother of Arian, Dritëroi’s son, her name is the name of a mother. Her departure led to the destruction of a family, but it was not her fault for that. The crime was committed by the dictatorship and the dictator. She, in a way, protected her child, herself and Dritërona herself. One thing is for sure, if Nina Aleksandrova had stayed in Albania, Dritëro Agolli would never have become, during the dictatorship, a member of the People’s Assembly, he would never have become, despite his merits, President of the Writers’ League and Albanian artists or even a member of the Central Committee of the Party.

Nina Aleksandrova left Albania, but not from the memories of the high school students of “Çajup”, who when they meet even now after half a century, remember her with respect, while the youthful stupidities, with a feeling of delayed remorse. Maybe she too has left a corner in her memory to the cheerful high school students of “Çajup”! From the report on Dritëroi’s trip to Russia, we did not learn, at least, even if Nina Alexandrova is in good health in her old age…!? Later, much later, from the memories of the poet Bardhyl Londo, I learned with a kind of sadness that: “Nina already had a deep depression crisis and had started taking medicine with fists …”!?

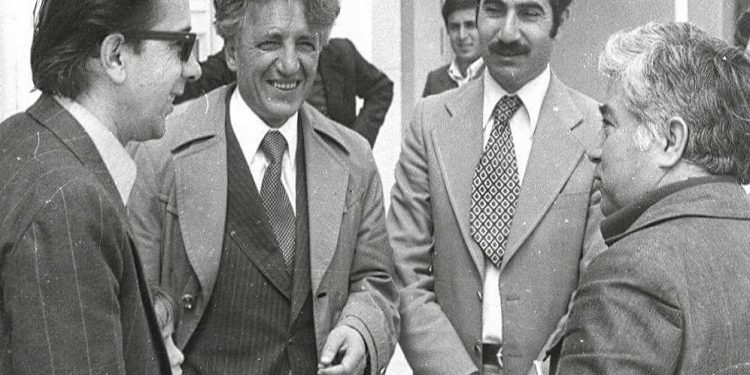

My acquaintance with Dritëro Agolli, the last one I met from the former members of the Central Committee of the ALP!

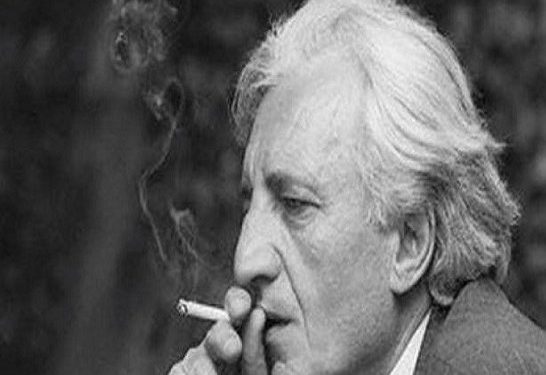

I did not meet Dritëronë in my high school years. Then and then I knew him only through the poems and novels he published and which I read with great pleasure. I met Dritërona during the years of democratic transformations in Albania. He was one of the very few communists who, at the last Congress of the Labor Party, had the courage to criticize the former dictator Enver Hoxha, to whom he had woven an elegy on the day of his death. He had the courage to break away from the past and look forward, towards a democratic socialism. In this Congress, the Labor Party of Albania became the Socialist Party of Albania. Dritëroi was elected leader of this Party, which in the struggle for power was and remains an opponent of the Democratic Party. In “Rilindja Demokratike”, I published at that time an article where I appreciated the literary treasure of Dritëro Agolli, but I also said that he “sees reality with red halves”! Today I do not judge so for him. Dritëroi was not and did not remain a fanatical communist. The red of communism did not prevent him from seeing clearly even when many others, who later became hardened Democrats, ran like bulls after her.

For Dritërona, at the time when I was the leader of the “Democratic Renaissance”, a short article was also published, which today I also judge as incorrect. In this article appeared Dritëroi and another writer, our charming former colleague of the “Democratic Renaissance”, Teodor Keko, drunk, shouting in the late evening in the streets of Tirana. The story was true, but there was no reason to use it to denigrate a political opponent like Dritëroi! There was no need to use it even against a young creator, a democrat with a soul, like Theodore, who had been engaged with his writings since the first issues of the “Democratic Renaissance” and who left it because he found himself free, without obligations, outside the quadrant of political parties. The newspaper “Rilindja Demokratike” was not, in fact, the one who decided to publish these two articles. The “Democratic Renaissance” was a body of the Democratic Party, and the Party headquarters was often required, perhaps every day, to publish critically commissioned articles. These articles targeted not only phenomena that conflicted with the line of interest of her and her executives, but, for the same reason, certain individuals as well.

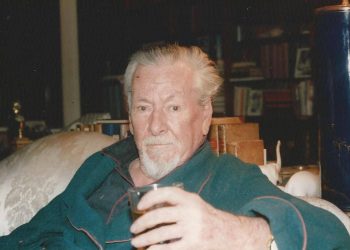

They often had a militant, exclusionary, if not annihilating, spirit. We thus thought we were defending democracy and considered ourselves the only defenders of it. We saw our political opponents as opponents of democracy. We forgot or still did not accept that the opponents were also part of democracy, that without them we would have a monistic democracy with pluralistic decorations. We forgot that this kind of democracy was very similar to what Ramiz Alia had once designed to preserve the communist monism in power. As students at the Faculty, we had learned, in Marxist philosophy, a pamphlet by Lenin entitled “Leftism, the Infant Disease of Communism.” It did not occur to us years later, in a democracy, to value blind and speculative militancy as a baby’s disease of democracy! A few days after the publication of information about Dritëronë and the drunken Teodor, I met Dritëronë at an official reception at the Hotel “Dajti”, which was then the most luxurious hotel in the capital. Dritëroi approached me and, after greeting me, calmly said: “information must give something new, unknown. You published information that tells about my drinking condition. And who does not know that Dritëroi drinks”?! He was right. We all knew.

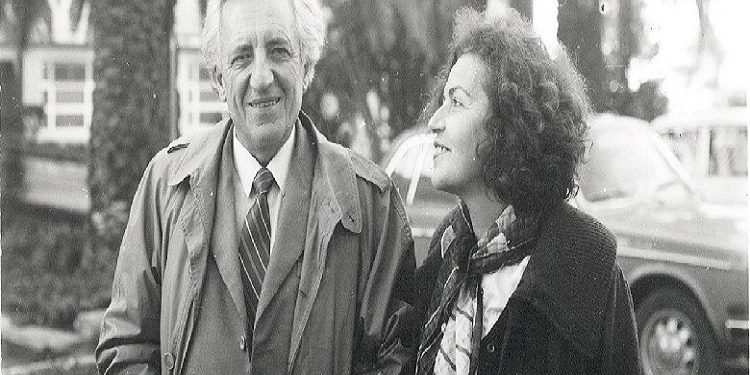

Dritëro Agolli’s proposal for the appointment of the new Albanian ambassador in Brussels, where I was!

In the years of democracy I met Dritërona also in the People’s Theater. We both went up on stage to say a few words from a friend on the anniversary of the great actor Kadri Roshi. I have not met him again. I have followed him in the interviews he has given from time to time in the Albanian press. In one of these interviews, in 1997, while I was still the ambassador of Albania in Belgium, he gave the opinion that in Brussels a personality should be appointed as ambassador, to whom all the doors of Belgian and European institutions were opened. Dritëroi had also found the person and did not hesitate to give his name to the press. He proposed someone from the Albanian diaspora of Belgium, who was held for personality, but who was not at all like that, who said that he had defended his doctorate, but that he had not finished any faculty, that he was removed with a lot of experience and promised to do his job. Great though, having more than half a century on his shoulder, he had not worked anywhere, not even for a day. Dritëro could hear the word. He was considered the patriarch of the Albanian socialists. His admirers did not even fail to declare him the patriarch of Albanian letters.

It seems to me that poets, generally people of art, often have doses of naivety and childhood not only in creativity but also in life. Is this part of their greatness when they are really big? Maybe! I, however, with or without Dritëro’s proposal, would be removed from the post of ambassador. This was safe and I was aware of it. In the context of the time, unknowingly, unintentionally, Dritëroi with his interview did me a little service. I presented it to the Immigration Office, along with a series of other articles in the Albanian press, where the Albanian embassies in Europe and elsewhere were described by our political opponents who came to power as “nurseries of crime” and so on. Such were the times. Not only the democratic wing, but also the socialist one, was in the years of militancy, infected with the infant disease of militancy. This is understandable. We were in the first steps of democracy and we were moving forward without recognizing it, just worshiping it. The bad thing is that even now, after 20 years of democratic transition in Albania, often the political class, acting irresponsibly, proves that it remains infected by this childhood disease.

INSTEAD OF CLOSURE

Albania became a prison of fear during the dictatorship. Everyone was afraid of everyone. The dictator was afraid of the people and of the comrades with whom he had killed and maimed a people. His comrades feared the people, but also the dictator himself, whom they had blindly served as obedient executioners. The people, too, were afraid of the dictator and his friends, the parents were afraid of the children and the children of the parents, the neighbor of the neighbor, the friend of the friend, the prisoner of the prisoner. For almost half a century, although not all of us felt the violence of the dictatorship equally, all of us, worshipers, neutrals or opponents of it, reproduced and lived in the great prison of fear and perpetual misery. I do not want in any way to equate the crime with the victim here. I just want to show the scale of the crime, the victimization of a people, of an entire country by a handful of criminals, by an ideology that served them to the last throes.

The sad irony of the whole Albanian tragedy is that its “heroes” have been forgiven even without apologizing. Under communism there were laws that protected dictatorship, but not laws that condemned it. This is understandable. Laws were drafted and passed by the people of the dictatorship. In democracy it turned out that the criminals had acted in compliance with the law, consequently they could not be punished! I do not know which “genius” mind came to this conclusion. In Albania, according to this logic, the top party and state leaders of communism were punished only for embezzlement. Calculations and expertise were done, which proved that they had drunk more free coffee than they deserved. So only here they had broken the law. Here the justice of the democratic state, do not forgive them! A special court gave them the only sentence they deserved! In this way, in essence, the justice of the democratic state also gave them the certificate of innocence for the crimes they committed. That’s why they do not apologize.

If justice does not punish them, logically and legally, they are innocent. There is a popular proverb in Albania that says: “Blood does not become water”. Indeed, in post-communist Albania, bloodshed, suffering, endless pain turned brown, state terrorism was taken under protection by the legitimacy of the dictatorship, which was overthrown. Even an absurdity in the country of fatally fatal after absurdity. It seems to me that if this had been done at the end of World War II, there would have been no reason for the Nuremberg Trials to take place. I am not adept at revenge, nor am I an apologist for crime. Justice in a democracy is not a continuation of the class struggle. The “heroes” of horror and hell could be forgiven, but only after being judged.

The question that the gardener of the Laç cemetery asked me, to which I could not answer?

I want to close these notes by mentioning a memory of the time of dictatorship. I was once at the Laç cemetery at the funeral of a friend of mine’s mother-in-law. During the occasional ceremony, I was slightly alienated from the others. At one point I was approached by a man, who as I later realized, was the gardener of the cemetery. He had a serious concern that he wanted to share with someone. The gardener told me he did not know how to act to maintain the graves. In the cemetery were both patriots and traitors, and enemies, but also communists, honest as well as criminals. He did not know how to deal with traitors, enemies, etc. If he did not take care of all the graves, the graveyard would be degraded in places, so it would turn out that he had not worked properly. If he took care of all the graves equally, it could be seen as crooked because in “everyone”, there were also the graves of traitors, enemies, etc. In this case, the correct attitude towards work would not coincide with a correct political attitude as assessed by the dictatorship. I was not able to give any advice to the gardener of the Laç cemetery.

Communism did not accept national or class reconciliation no longer for the living, but neither for the dead, the enemy was the enemy even after death, the bourgeois remained the same even after being buried. The land had remained unclassified. It was not divided into bourgeois and proletarian, in patriotic and treacherous.It was not divided into such categories was also death. It had the same face for everyone. What can I say? More than 30 years after this meeting in the Laç Cemetery and after about 20 years since the overthrow of communism, I can say that in a democracy the “heroes” of crime, those who martyred an entire people, who “heroically” ate each other’s heads the other being “People’s Heroes”, can sleep in eternal peace next to the victims, equally covered with flowers and care. The class war, at least after death, seems to be ending in the land of the Albanians. You can call this a good start./Memorie.al