Part One

Memorie.al / He had lived as a Pasha and an Ottoman governor of the Catholic faith. He had passed away far from the country he loved so much, and for which he had written one of the most beautiful poems, so much so that there was no compatriot who did not know it. Fate had reserved for Vaso Pasha, 86 years after his death, a return to his homeland in a “grave without a cross.” On the 100th anniversary of the League of Prizren, the ruling communist regime, after much effort and peripeteia, would bring the “father of Albanianism” back to Shkodër, where he was born, re-burying him according to its own custom.

The two following narratives tell the adventure of the return of Vaso Pasha’s remains to the Homeland in the distant year 1978. The protagonists of the narratives are an Albanian diplomat and a journalist from Lebanon. Dalan Buxheli told the story in an interview given many years later to an Albanian newspaper. Meanwhile, Melhem Mubarak wrote the story of the return of the remains himself in the Albanian Catholic Bulletin, which was published in the USA in the 1980s and 1990s.

THE FIRST NARRATIVE

Dalan Buxheli, former Albanian diplomat in Egypt

“The return of Pashko Vasa’s remains was one of the most important events of 1978, which coincided with the 100th anniversary of the League of Prizren. At that time, I was part of Albania’s diplomatic mission in Egypt, which also covered Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, and a part of the African countries.

The operation for the return of Pashko Vasa’s remains, in which I also participated, was entrusted to a group of Albanian diplomats operating in that distant part of the continent in the spring of 1978.

We had visited Pashko Vasa’s burial site several times in the Ottoman cemetery of Hazmieh in Beirut. Vaso Pasha rested in a shared grave with his wife, Katerina Khanum. Their burial site at the head of the cemetery was visible from afar. Locals had erected a characteristic building over it and brought flowers and candles there at all times.

The honors paid to Pashko Vasa by them related to his contributions to the self-governance and prosperity of Lebanon. In the Lebanese encyclopedia, he is recognized as a figure with extraordinary contributions for the time. A tall monument to Pashko Vasa was erected in the western part of Beirut.

The truth is that the Albanian state had made no attempt to repatriate his remains until 1978, even though Vasa’s role as part of the National Renaissance was widely articulated. In the spring of 1978, I was the first Albanian official to knock on the doors of the Lebanese institutions.

The authorities in Beirut would not, under any circumstances, grant us permission for exhumation. Among other things, the fact that Vasa’s burial place was a waqf (religious endowment) was the main obstacle. It took us some time to negotiate until we received their approval.

When I failed several times in a row in negotiations with local officials, I decided to ask for help from a friend of mine, a well-known journalist not only in Lebanon but also in the West, who responded immediately and used all his contacts to pave the way for the “Albanian operation” for the return of the former Governor of Lebanon’s remains to Albania.

He was a sincere friend of Albania and the Albanians, who followed the operation for the return of Pashko Vasa’s remains from the first moment until the burial ceremony in Shkodër.

His name was Melhem Mobarak. I had visited his house in Beirut several times, where he had a special library with 20 thousand Albanian books. He knew the history of our country well and was constantly interested in the news from Tirana.

Mobarak, through my intervention, visited Albania several times and published a series of articles related to the Albanian reality. He became the organizer of the ceremony held in Beirut on the occasion of the repatriation of Pashko Vasa’s remains. The event began on the morning of May 31, 1978.

The remains of Pashko Vasa and his family members were placed on a high podium, on the sides of which Lebanese guard soldiers stood honor watch. A large number of citizens and local authorities came for the occasion. Different people spoke there.

The main speech was delivered by the head of the Albanian Community in Beirut, an early emigrant from Gjirokastra with the profession of banker, who knew the developments in Albania up until the war. The representative of the Lebanese government spoke. The Ambassador of Turkey in Beirut offered a greeting.

Following them, Pashko Vasa’s family members and our diplomats in the region took the floor. The gathering lasted about two hours. Pashko Vasa returned to his birthplace in Shkodër after 86 years. In his diary, Melhem Mobarak wrote: “Fate is truly whimsical.

Vaso Pasha, who had declared that; ‘the faith of the Albanian is Albanianism,’ I do not believe he would have imagined that this slogan would be applied to his remains, as they were being taken from a religious cemetery to be buried in Shkodër, in a grave without a cross”!/

Later, Sulejman Tomçini presented his credentials in May 1978. I helped him in all the steps that led to the final return of Vaso Pasha’s remains to Albania. And on May 31, we were at the official ceremony held in the Hazmieh cemetery.

A troupe of officers performed military honors before the three coffins covered with white cloth. High local authorities were present there, including: Y. Rassy, Mohafez of Lebanon, Colonel Dargham from the High Command of the Army, G. Kassouf from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, G. Feghali, Mayor of Hazmieh, and O. Arghit, the Turkish representative for foreign affairs.

Members of Pashko Vasa’s family were also participants in the ceremony. Several speeches were held for the occasion, and in the end, all the rites of the ceremony were carried out. The three coffins departed by air for Albania that same day.

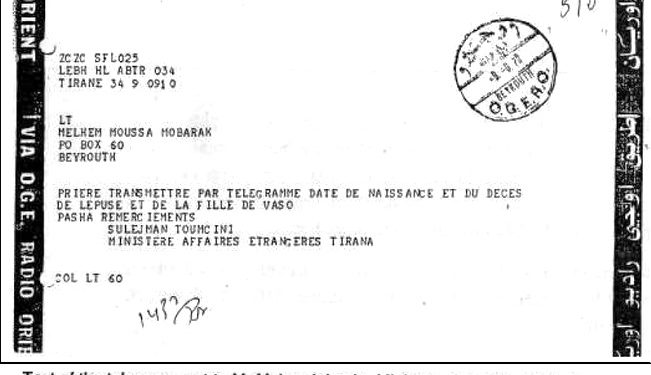

The epilogue of this story happened a few days later when I received a telegram from Sulejman Tomçini in Tirana. He asked me for the exact dates of birth and death of Pashko Vasa’s wife and daughter, so they could be buried in the National Martyrs’ Cemetery in Shkodër.

Fate is strange. Could Pashko Vasa, who wrote the famous verse: “The faith of the Albanian is Albanianism,” have thought that one day this would be symbolically applied even to his remains, exhumed from a religious cemetery in Lebanon and placed in a grave without a cross in Albania?!

The Albanian Adventure of the Journalist from Lebanon

But who was the journalist who not only made the return of Pashko Vasa’s remains possible but also followed them to his homeland? The following information is recounted again by the Albanian diplomat Dalan Buxheli:

Melhem Mobarak was the only son of two Lebanese diplomats from Beirut. After graduating in journalism, he became well-known not only within the country but also outside it. He left his homeland at the peak of the war between Christians and Muslims and settled in Montreal, Canada. He knew Albanian, was polite, and benevolent in communication. In Beirut, he had organized an extended community of Albanian emigrants.

With their associations, he occasionally carried out activities promoting the traditions of our people. Sometime around the end of the 1960s, Mobarak traveled to Tirana. He was interested in visiting Pashko Vasa’s birthplace, and even went up to Kelmend. When he returned, he wrote in the local press about his impressions of Albania.

Bringing back impressions from Northern Albania, he expressed: “In the land of the eagles, God no longer exists. In Bogë and Theth, only goats still graze around small ruined churches, surrounded by abandoned fences and cemeteries, with broken crosses fallen to the ground.”

For Mobarak, Albanian atheism was something absurd, and as such, it was inconceivable. He visited our country two other times and explored further into the Albanian spaces. He wrote other articles, trying to somewhat avoid the topic of religious belief. In his next visit to Albania, he intended to meet Enver Hoxha.

When he arrived in Tirana, he made an official request, but it was not approved. Apparently, someone expressed doubts about him as a journalist placed by anti-Albanian circles, and he was not allowed to contact Enver. Upset by the authorities’ response, Mobarak tried to secretly enter The Block, but the adventure proved unsuccessful. In fact, this foolish attempt cost him dearly.

Handcuffed very close to Enver’s villa, he ended up in the police cells, where he was subjected to endless questioning for days on end, which he said were brutal and meaningless. In the early 1990s, he came back to Tirana. He went to Shkodër and visited Pashko Vasa’s burial site. Memorie.al