By Ahmet Bushati

Part fourteen

Memorie.al/After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

Shkodra in the first years under communism

Generally, the attitude of the citizens of Shkodra towards the communist regime in its early days!

Meanwhile, even after the liberation, as once the war, it would have its loyal and enthusiastic supporters, however few in number. There would thus be a category of people who would consider and feel the new government as their own, a category of people who, after having spent two or three years of persecution during the War, would see themselves saved and free, as well as proud of the war they had fought. These people would also feel happy for the future that smiled upon them with all grace. To this mass of people it would seem that the sky had come down to earth, that everything was shining everywhere, without day or night, if there were always other people who, like themselves, were pursued by the government, imprisoned without being spies or traitors, who had families who could drive to their homes to drive them somewhere in exile, who could be shot without having their hands stained with blood and without having sought to overthrow their government by force, as they would be unjustly accused by their appointed prosecutors.

So, there was also this small mass of people who, in contrast to the other large mass, felt happy that the days were dawning and darkening with an unprecedented joy. There would be nothing that would even slightly diminish the image and trust of that blood-earned power among that mass of people.

Members of these families would be present wherever there was an event, a manifestation, an inauguration of any insignificant work, or when a person considered by them to be a “criminal” passed by with his hands tied in the street. You would see these people wherever there was any activity, which could be a random concert with only partisan songs, or a half-hour sketch, as always with a partisan theme. And you would see them especially when the “people’s courts” were opened, in the boxes reserved for them.

Meanwhile, it must be said that there were also families of martyrs who showed the joy of freedom with restraint. The youth, for its part, once actively involved within the National Liberation Movement, had shrunk in two moments by that time: firstly with Mukje, when the image of the National Liberation Movement was ruined by the authoritarian presence of the Yugoslavs in determining the fate of Albania, as well as by the war itself, which had not had a liberating character, as had been propagated, but rather a social one with a strong ideological emphasis; and secondly, the period after the liberation, which instead of the freedom and rights promised with so much fanfare, had brought oppression and misery.

Of all that vast mass of anti-fascist youth during the War, only a small part remained, organized in the “B. R. A. SH.” (Union of Albanian Anti-Fascist Youth), with headquarters in the beautiful building of the former Italian consulate. There, the enthusiasm of this group of young men and women was evident, who seemed very friendly in their mixed and free company.

You would often see them singing partisan songs and more often chatting among themselves very lively, laughing as well, and sometimes trying to learn to dance. Unlike what we had previously observed about some “peasant” partisans, these young women we are talking about, who were citizens and in civilian clothes, seemed very sympathetic for the sincerity and agility they manifested, for their proud and honest “demeanor”, as a result of an emancipation won by the war and freedom, in which case, not only had they escaped from previous social prejudices and rigid rules that time had imposed, but also because they were learning to live according to the latest feelings and convictions they had acquired, with the certainty that this ensemble of young men and women, numerically few, was experiencing unrepeatable days of happiness.

Finally, while the greater part of the people had begun to suffer the dictatorship, another part of the people, although modest in number, was enjoying days of true joy, making the Albanians, although brothers and sisters among themselves and under a small piece of sky, for the first time living separately and with different destinies, to turn after a while even into enemies for husbands and wives. Thus there are 117 names of merchants, who, with their brothers and partners, went to about two hundred or more families of great merchants, many of which were old and had served Shkodra for generations. The blow that the communist government had dealt to the merchants on this occasion, would be reflected greatly in the mass of the people, and especially in the elite of the city, of which they were part.

For years, the Sigurimi investigators would continue to deal with merchants and sengsera, in connection with the gold they demanded from them without permission. The respected merchant, Ibrahim Hoxha, would die in prison for gold dealing, as would the well-known sengsera in Shkodra, Kel Jerdha, Muhamet Spahia, Gaspër Doda and others. In connection with the so-called “irredeemable debts” to the state, some merchants would suffer years in prison and their harassment, often with the aim of cutting off any possibility of communication with their families, would be numerous and diabolical. For example, after taking everything he had, the Sigurimi investigators would also demand gold from the respected merchant Zef Muzhani.

Initially, the Shkodra Sigurimi investigators would deal with him for gold dealing. To avoid any possibility of communication with his family, he would be transferred to be interrogated at the Ministry of Internal Affairs in Tirana, while his family, uninformed about the transfer, would continue to bring him food every day, in the prison near the Sigurimi in Shkodër. When after a few days his family understood the diabolical move of the Sigurimi, they would run to Tirana with food and clothes, but Zef Muzhani would be transferred to the Durrës investigator the very next day, and again when after a few more days the family had tracked down his latest movement, Zef Muzhani would be sent to the Lushnja investigator, to finally end the game after a few more days in Shkodër.

The city government, through the “neighborhood councils”, would occasionally organize inspections of the homes of citizens suspected of having stored food above the legal limit. In such cases, the homes of former merchants would be targeted. It would be enough to find even 2 kg of corn in one of their homes, and the head of that house would be publicly disgraced in the most humiliating way, just as if he had committed a real crime. For such ridiculous quantities found during inspections, we would read in the press the names of former merchant families, such as Karemani, Ulqinaku, Deda, Ljaria, Negri, etc., etc.

Thus, the press would advertise with great fanfare, such as the cases when F. Veseli’s family was found to have stored 30 kg. of grain; in the house of M. Tirana 2 kg of wheat and 4 kg of flour; in the house of Q. Dergut 6 kg of flour and 3 kg of wheat, etc. When Kareman aga was ordered to hide 7 kg of flour, the press could hardly wait to write word for word: “This unscrupulous element, who wanted to hide 7 kg of flour from the government, just to avoid giving it to the poor people, in violation of the order, is sentenced to three years in prison for this”!

Such were those times, when the deepest misery and the draconian laws of the communist government, ruled with terror the lives of a people under complete oppression.

Bërdiciani

If there was a city in Albania where the news of an event, especially in cases of imprisonment and murder, spread quickly from mouth to mouth throughout the neighborhoods and was experienced with more or less the same emotion, this city was our Shkodra.

One day towards the beginning of February 1945, a car with eight men on board, tied hand in hand with ropes, had left the large prison of Shkodra towards Zallin i Kirit. The light had just begun to dawn. By the time that car had started moving, the last man in line had begun to slowly release the hand that was tied to his companion next to him. None of the partisans sitting in the back of the car, right next to him, had noticed his movements. The moment the car entered the bend in front of the City Hall, the Bërdice man, who had completely freed his hand by then, flew out of the car and onto the ground, and with a single run through the numerous bullets, he safely crossed the long courtyard of the high school and finally disappeared without a trace.

The incident was immediately known and spread throughout Shkodra. Even we, as young people, would talk about that event that day. Likewise, even when we returned home for lunch, we would find this news. All of Shkodra within a short time had received and happily conveyed the joyful news of the salvation of a death row convict from Bërdice, to baptize him from that day with the name “Bërdice man”. After a few days, it would become known that that “Bërdician” was a certain Haxhi Ahmeti, about thirty-three years old, physically developed and very energetic. As a family, he had his origins in Kastrati, and had been in Bërdicë for a long time for blood work.

After the liberation, Haxhiu and his uncle Veli, as influential families in that area, would be elected heads of the “Councils”, the first in Upper Bërdicë, the other in Middle Bërdicë. Involved in the Bërdicë incident, they were both arrested and sentenced to death. On the day Haxhiu narrowly escaped certain death, he had gone to Dobraç, to a house named Kasemi, a friend of his who, despite being linked to the government, as well as to the war that had been going on, continued to remain loyal and to be a good Albanian. Even though the owner of that house that day had a group of partisans inside, he would not only give his friend’s son food and shelter, but would also equip him with weapons and, as was customary, accompany him to Vukatanë, from where other loyal members of his household would take him by boat across the Drin, to his area of the three Bërdicas, Malihebaj and Beltojë, which, as long as he remained a fugitive, they would feed and protect him as if he were their own son.

In retaliation, Haxhiu’s house was burned down and his young wife and two minor daughters were exiled to Berat.

Seven or eight months ago, on a rainy autumn day, Haxhiu happened to be outside in the village of Derragjat on the Buna Coast. To escape the rain that was increasing by the minute, he headed for a hut that he had noticed in the middle of a field. By coincidence and to his worst luck, a squad of partisans of the People’s Defense had started running towards that hut at the same time from another direction. Haxhiu was cornered, he had no choice but to get away as quickly as possible, while the People’s Defense forces, who were at close range, recognized Haxhiu and tried to capture him alive, but Haxhiu opened fire immediately, killing their commander on the spot, an officer with the rank of second lieutenant, and running without a path, he managed to escape this time too by throwing himself on the back of a horse that was grazing in a meadow. They rode him, village after village, and in one breath he arrived at the distant Paçram, where a sister was married.

It is said that this horse, which its owner had been searching for without success, had been the reason for the Sigurimi to follow Haxhiu’s footsteps, and on May 18, 1946, after a full year and a half of escape, Haxhi Ahmeti, while standing hidden inside a wheat field in his village of Bërdica, was surrounded by numerous pursuing forces from all sides. Haxhiu had responded to their call to surrender with the muzzle of his rifle, until after two or three hours of fighting, the cartridges in his long rifle ran out, and he, determined to the end for an honorable death, took out his revolver, his last hope, and with its muzzle pointed at his head, killed himself.

The death of Haxhi Ahmeti – the man from Bërdi – Shkodra would suffer as if it were a man, it had known and loved before. During those three or four days after the murder of Haxhi Ahmeti, I was not in Shkodra, but I remember that the day I returned home, my older sister confronted me and that her first words, uttered with great sadness, were: “Ahmet, they killed that man from Bërdi. It hurts everyone.”

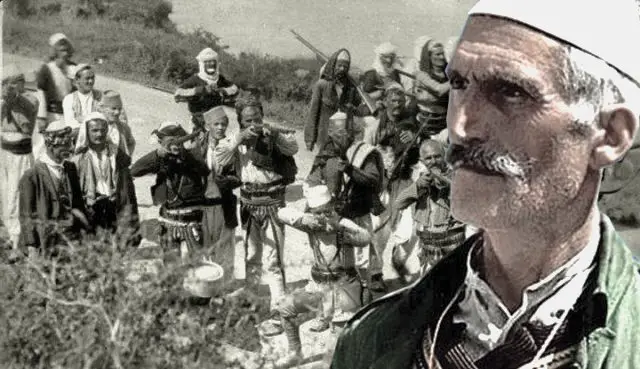

The Uprising of Postrriba

Postrriba has been connected to Shkodra all her life, she had been present at all its important events. Without delving into history, during which the Postrriba people constantly prove that they are distinguished for their loyalty, bravery and patriotism, it is enough to recall just a few moments from its recent history, to prove the above, it was the Postrriba people who in 1835, led by Hamz Kazazi, supported the uprising against the Turks, an event about which the verses of a song speak:

“Two hours before the light went out

Postrriba reached

Postrriba like a cloud of weather

She is going to the ball with a scythe.”,

these verses, which sound like a permanent refrain of hers, because whenever Shkodra was involved in an important event, Postrriba would be by her side. Thus, in 1913, when Shkodra was surrounded on all sides for six months by Serbo-Montenegrin forces that attacked it relentlessly day and night, the postrribs under the leadership of their brave, Adem Haxhi, would wage real battles, among which the one of Bardhaj, as bloody as it had been. Likewise, again with Adem Haxhi at the head, in 1920, in the war of Koplik and precisely in that of Moxeti, the postrribs would perform rare acts of bravery, as the postrribs had done those who, on some occasion, with their presence in Shkodra, might have avoided its plundering. Even in the first week of April 1939, on that dark eve of the invasion of Albania, Adem Haxhia at the head of three hundred Postrribs, would ambush the Italian army in the hills of Bërdica.

During the last war, the entire area of Postrriba had been a safe haven for any fugitives and especially for the partisans who had started the war earlier than the others. Whenever the partisans, under the shade of fig trees, grapevines, or even around their tables, would brag about the Albania of the “miracles” after the war, the Postrribs, for their part, would not hold anything against them, for the young age and good intentions of those young and naive partisans, as long as they carried the long rifles of war on their shoulders.

When, two years after the war, Postrriba was preparing for an uprising, the traces of the partisans were still fresh everywhere in Postrriba, and when that uprising failed and the entire area caught fire, and even though many of its men were shot and others filled the prisons, the former “angelic” partisans who had once poured honey from their mouths would not even leave them alive, even if the barbarity of their power over that patriotic and generous people – who until two years ago had ambushed and shot them like their own sons – were somehow less cruel.

The villages of Postrriba, scattered here and there among the rocky cliffs at the end of the proud Maranaj, were no longer patient and began searching for their comrades. Large rooms of old houses and sometimes even hidden caves, would be the environments where the leaders of Postrriba would gather several times among themselves. Murat Haxhia, a Shkodra resident, as the main organizer of the upcoming uprising, had long ago abandoned Shkodra and moved to Postrriba, holding his honored place in every meeting. Assembly after assembly, and one day even their last words had been: “Let Shkodra fall, let it fall as long as it is without taking our boy soldiers”!

At the time the Postrriba uprising was being prepared, the escapees in the mountains were numerous. As we have said above, in the Dukagjin mountains alone they numbered in the hundreds at that time. The Mirdita area had many escapees, led by Mark Gjomark. Among the mountains of Puka, besides the Mirakajs, there were many other fugitives, as there were further afield, in the Tropoja River. In the meetings held by the leaders of these fugitives, it was agreed upon for a joint attack by them at a certain time, with the aim of liberating the entire north, including Shëngjin, as an opportunity for the landing of the allies.

The Postrriba, for its part, either did not show patience in this case, or was not aware of a higher plan. Perhaps the Postrriba’s mistake was that they necessarily linked the fate of the uprising to the fact that on September 9 their sons would join the soldiers, thus missing the uprising. To finally decide whether or not to raise the banner, the leadership of Postrriba called a meeting for September 8, for which a reliable courier informed the leaders of each village.

So, on the appointed day, September 8, the meeting of the three bajraks of Postrriba was held at “Kodër Boks” and precisely at the place called “Shegat e Ibros”. The meeting was chaired by Osman Haxhia, brother of Adem Haxhia from six years ago. Representatives of the three bajraks, such as Abdulla Seiti, Selim Rraci, Smajl Duli, Muho Dyli, Emin Zyberi, and with the word taken from Myrto Dani, the bannerman of Drishti, who was absent that day. The meeting decided that the next day, September 9, before dawn, all the fighters would gather in Fushe i Shtojit to attack Shkodra.

It had not yet been a day when three hundred men had gathered at the place designated the day before. Most of them had weapons, and a small part was equipped with circumstantial means, which certainly expressed the great determination of Postrriba for war. As soon as they broke the telephone connection with Shkodra, they set off towards it with the belief that Shkodra would respond to their rifles with rifles. Many family members of Fusha e Shtojit had come out in front of their houses and watched with curiosity and emotion those determined and proud warriors who quickly crossed their field, on which occasion there were also some of them who joined them.

Starting from the purpose and seriousness of the mission on the eve of the war, it makes us believe in a special spiritual state that those fighters must have experienced and in an atmosphere that, the closer they got to Shkodra, the more solemn and encouraging it must have been for them. However, we know that when they arrived on the outskirts of Shkodra and precisely at the barracks at its entrance, the sun had not yet set on the ground, under the powerful signal “Fall, men!” they quickly passed the barracks and houses surrounding them and opened fire from many directions. The army, on its part, rose to its feet from the first rifles, but surprised by the sudden attack, would not have sought anything else for a while except to defend itself. Residents of the surrounding area would tell us from that day how the robbers had climbed over the walls with guns in their hands and shouted “Hey, you Stalin’s puppies….”! Memorie.al