By Andon Lula

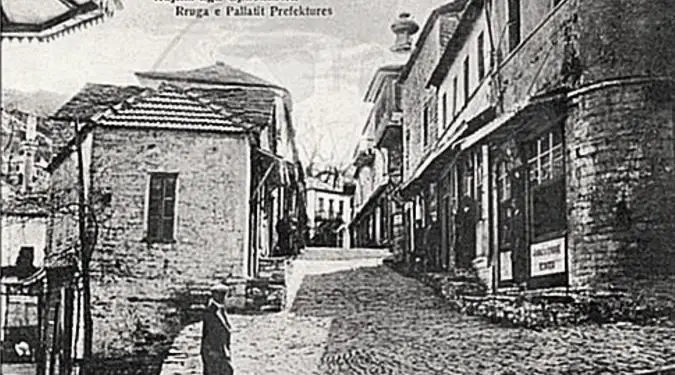

Memorie.al / The first year after the war, January `45 in Gjirokastër, entered with cheers and cheers. In this atmosphere, Thoma Papapano felt like he was on “thorns”, but in the “eyes of the world”, he appeared as before; Gentleman, quiet, thoughtful, careful, with authority and shadow. He dressed nicely, in a suit and borsalia, in the winter with the “Gub” coat that Fan Noli had sent him from America, while in the summer with a dock suit, beige, white shirt with a collar over the jacket. Someone, and jokingly, kindly advised him to wear a cap, fashionable for the time he had arrived.

Outside of work, he spent his time at the Old Bridge, rather than commenting on the politics of the day. Here he fished with the most famous fishermen of the city. And not without reason: He thought that the curtain of his time was slowly falling.

He was seen with a different eye, they did not mention his “first works”, national even though in the historical background of the past, he was present at important events in Gjirokastër and far from it, such as in Elbasan, Tirana, Vlorë and Shkodër, from 1908 onwards, active participant in them, for the opening of the first Albanian school Liria, the declaration of independence and the support of the Independent State, in defense of the country’s borders, as a representative in the European offices.

And further still. In the Fanolist Movement, for political-democratic reforms and emancipation of the Albanian society, supporter and sympathizer of the Anti-Fascist National-Liberation War.

He also felt alone. His contemporaries had left the country or were separated from life. A man, Vangjel Koça, publicist, father’s friend, near and at home, with whom he exchanged books in French, no longer lived.

The new policy had labeled him and Branko Merxhanin, with whom in the 1930s and above, he talked about “Neo-Albanianism”, as its creators, spokesmen of the reactionary ideology, which aimed to separate the mass of the people from their positions of the class war, and threw it into the positions of bourgeois nationalism.

In these circumstances, previously, Branko Merxhani had left and lived in Turkey, while Vangjel Koça, in an attempt to leave the country, towards Italy, had drowned by ferry in the waters of the Adriatic. Jorgji Meksi had also passed away, one winter night, in solitude, Lefter Dilo, from a village with him, had found him lifeless, near the hearth of the fire…!

In this period, “Varoshi”, his neighborhood, the “aristocrat” neighborhood, with a name and opinion that has not been lost even today, was going through a difficult situation. With the new developments of the communist regime, fear, insecurity and seizures were present.

Some, rich merchants, had left the good rooms, for those coming from the war; they had tangled ties and republican hats, trousers with a strong line, they had hidden gold watches; in silence and without a sound, they were waiting for the big bills, which they had to pay for the coffers of the new state, others had taken the road, Tirana and Durrës, now escaped, abandoned like the houses, where life was missing.

He experienced the arrest of Thoma Kola badly, with pain, with a house in front of him, a life with entrances and exits, separated by an alley. To this aggravated situation in the entire neighborhood, an anonymous poet attached the verses:

“What is wrong with Varoshi who is crying,

They raised the air,

With mattresses and quilts,

with pots and pans…”!

So Papapanua, alone, with an easy step, every morning made the way up to “Varoshi”, with shops on both sides. In some he rested. It was still served at Minushi’s grocery store, at Stathi’s bakery, at Gega for yogurt and sweets, at Teli Mihali and Kotrua, for sewing and embroidery, as well as at Hani e Manga, the carpenter of Naka, but not at Hadër Latia.

The other artisans, some of the former company of “Opinga”, supporters of Fan Noli, on the verge of bankruptcy, had lost their first life and were working for a living. Still private, burdened with taxes, twice or more, so that the service shops of the new state would have the upper hand.

Thomai, the son of Gaq of Xuhanos, 50 years tinsmith in his first trade, but also a watchmaker, mended umbrellas and “pulled out broken teeth”, had removed the advertisement “Trader and tree seller” from the shop.

Someone had advised him: “There is no more free market”, and, as a private, with a copy pencil, the tip of which was wet with saliva, he made the last calculations, to join others in the state enterprise, to services.

Others had joined before; Vaso Bashari and Tolo Çabeliu carpenters, Nako Urra, who worked the wood for doors and windows, cradles and tabuts, but who still played carnivals in the role of the captain, Zoto Naçi, barber, where Papapanua was shaved, on the first Saturday of every month.

After the lesson, on the way to “Varoshi”, on the way down, for a while, he returned from Kola, where he sold cabbage and dried fruits, to Polo Donua, just to greet him, specializing in Greece, but without the first clientele, he continued to be sewed men’s shirts.

He no longer went to Qirjako Naçi, for anything, while at Pandeli Majko, where he rested for a while to fix his umbrella, his path was cut off because he, after his son, in military school, had occupied Tirana.

The street, without people and half empty, seemed smaller to him. So, the shops, the houses and the courtyards, silent. Only in the big yard of Lolo Man’s big house, occupied by “newcomers”, some, military families, where different dialects were spoken, there was movement. The children, in shoes with soles and moccasins played war games, with pits and swords.

Even the advertisements in which it was still read: “High quality goods”, “Here you can find the latest fashion, Paris, Rome and London” did not make an impression anymore. Otherwise, some time ago. He read them one by one, word for word. Everyone knew it. If he found a spelling mistake, his eyes would be damaged and the “jinns” would ride him. “The bars, he said, these are for the 7 windows”!

In the once peaceful neighborhood, where everyone was at home and at work, many things had changed, there was more talk of expropriation and violence. With soldiers and soldiers, confused mules, moving laden with food and wood, against the gray background of the new regime, it resembled a barracks.

These images and aggravating situation caused Papapanos sadness and loss, dimming his strength and optimism at the beginning. Many things he thought. The new policy, the “cenet”, went through the eye of the needle.

Labeling; “aristocrats”, “bourgeois”, as some party extremists said, caused him boredom and bitterness, but he continued to remain, the first Papapanua, politically uncommitted and undisturbed in party life; to be oneself, with a mind and spirit that had grown up and formed, renaissance, freedom-loving, with a democratic worldview and western culture, to swim in “its waters”, peaceful, close to patriotic and intellectual life, “away from politics”.

However, in close company, he expressed that he was adapting little by little to the new system and that he had a hope, that something would change in his favor. Several times he had the courage to write to the Commander, Enver Hoxha, the former student, now in charge of the country, but he had given up. One of his friends advised him: “Look around, what’s going on! Why do you appear unhappy, or do something wrong”!

And to himself, under his breath, he talked and remembered, intellectuals and friends who had “eaten” him, some from large families of the city, after the first visit of Enver Hoxha, in `47, such as Aqif Kashahu and Sheraf Karagjozi . One of his close friends, who supplied him with books, Alizot Emiri, for example, was inside, in “7 windows”.

But it happened differently with him, he did not have the black fate of some intellectuals, even the Girocastrians, and friends with him, who instead of the bullet ate the prison. As long as he lived, in the years of the previous regime, he remained “the first Papapanua”, he lived a quiet life, in peace with himself and others; was appreciated, as it is remembered even now, in democracy, an honored figure of Albanian education, with a well-deserved place in Albanian historiography, a prominent personality of our national education and culture.

At the behest of Enver Hoxha, he was assigned a special pension and, in the gymnasium, 5 hours a week, to teach the Albanian language. He felt satisfied, proud and protected, when the Great sent him a suit as a gift. It was not held. Some peers became jealous. It happened a few years ago, when Fan Noli from America sent him a big “Gub” coat, and the poet Ramiz Harxhi hurried to tell him: “I will write to him. And why does Noli have a coat, a piece of bread”!

As we wrote above, the “sufferings” belong to him for a short time after the 50s, he was in the spotlight, for good, at the head of the trapeze, in all national holidays, in every local and wider activity, word- heard about local and national education problems, about people’s complaints, to which he raised his voice and fought for their solution.

Charged with important tasks, he became a member of the People’s Assembly for 4 years, was elected in central and local forums, was awarded orders and titles, even “Teacher of the People”. Memorie.al