By Prof. Asst. Dr. Albert P. Nikolla

Joana Doda

The second part

-Anthropological view on the persecution of scientists during the years 1945-1955 – the case of engineer Gjovalin Gjadri, the observer of communism-

Memorie.al / The case under consideration is subject to a multi-level research methodology, which is dictated by the personality of engineer Gjovalin Gjadri. After studying in Austria, engineer Gjadri had a five-year work experience in the Soviet Union. Based on this data, we will observe some anthropological dynamics of the relations between “socialist” and “capitalist” science. The influence of the Austrian study experience, the work in the Soviet Union and later in Albania, lead us to look closely at the cultural dynamics of engineer Gjadri’s behavior towards the issue of work remuneration, under the perspective of economic anthropology.

Continues from the previous issue

Gjadri can neither be considered a “new man” nor a reliable person of the regime, as he “has always looked at the money and personal interest”. This issue has a great anthropological weight, as it brings to our attention the dynamics of economic anthropology, in the relationship between regimes and scientists. In the first years of the communist regime in the Soviet Union, where Gjadri worked for five years, there was a mostly negative approach of the government, against the demand that scientists and intellectuals have for high salaries. Lenin was a great opponent of high wages:

“It is indisputable that high salaries have a great corrupting influence on our Bolshevik power! But the speed of the development of our Revolution has caused us to be forced to join us by some intellectual adventurers, who demanded high salaries, causing the public money of the working masses to be wasted. It should be explained to the masses that paying intellectuals high salaries is unprincipled, but we did it out of extreme necessity.”

Even the Albanian regime wanted to adhere to this line. Self-interest has been demonized throughout the time of socialist power. Even art was put to the function of the fight against self-interest. Artistic works should condemn any tendency to put personal interest above the general one.

The best works of this period educated people with new thoughts and desires, they kneaded in their consciousness the socialist attitude towards work and common property, the spirit of collectivism and putting general interests above narrow personal interests, they educated those with boundless loyalty to socialism and a spirit of hatred for class society and its morality.

Looking at the part of Gjadri’s file, where it is written about the debates on the salary, one can notice an interesting fact: the ministers promised him a salary increase, but they did not keep their word: “In the plenum of July 20, 1949, the discussion of Gjovalin was important Gjadrit, who requests an increase in his salary. The ministers have promised it for years, but it still hasn’t changed. He emphasizes that it is unfair and contrary to the labor law, which defines both doctors and employees. Meanwhile, doctors receive 8,000-9,000 ALL.

Looking at the salaries of engineer Gjadri, at the time he was director of the Directorate of Roads and Bridges, we discovered from the archive that his salary was 1,850 ALL. The basic salary was 1,600 ALL and 200 ALL benefited him, for the qualification he possessed at that time, he had rank III; he also received 50 lek, bonuses.

Gjadri is outside the social, cultural and spiritual climate in which he grew up, was educated, and worked. Everything in the first years of the regime seems so gloomy and unaffordable that he asks to leave Albania in an official way. The request he makes to the government to leave Albania is placed in his file, under the heading “Compromising material”:

“The deprivation of rights reminds me again of the early days when I was a student in Austria, where I felt a lack, I felt a suffering, that I don’t know what it is, but that I now know, that they have the suffering of the absence of the Motherland, which I have always looked for and I have never found, as here in Albania…! But in my degradation, I am convinced that my rights and claims here in Albania are unrealizable… I want Albania to leave this. I have a mother and a sister in Austria, who are suffering economically, according to the news I received…! I’m begging the ministry to release me from any duty and with the mediator where necessary, for the issuance of a passport so I can go to Austria”!

This is the height of despair for a person who loves his country, but who sees himself as a stranger, with this power. We will find this way of expressing with strong emotional notes below, following the article, when we look at his book, ‘Letter to my wife to die’. Gjadri is a free spirit, the rules of the dictatorship are very close to him and he has no desire to stay in his homeland.

Even indifference was not seen with good eyes by the regime, as it insisted that every person, especially the intellectuals, be involved in the fight against the occupier. In this context, we also recall the criticisms of social opinion in socialism, where this mentality of remaining uncommitted and passive in social and political life was categorized as “indifference”.

“Passivity and indifference are foreign phenomena, not only for communists, but for every honest citizen of our socialist society…! How can a communist, even a citizen, remain indifferent when… he sees that someone does not respect proletarian discipline, when someone does not behave according to the moral norms of our socialist society, at work, in society and in the family”? “Comrade Enver Hoxha underlines that; the indifferent “are more dangerous than the guilty themselves, because the indifferent harm the development of social opinion”.

To be classified as indifferent was a step towards being considered an enemy of the regime. All the analysis of Gjadri’s file and the other consulted archives lead us to affirm that Gjadri has always been considered an enemy, but due to the great need the regime had for his knowledge, he has been kept under constant surveillance. In fact, in the file we also found his categorization, as an enemy element, in category 2/B, which is indicative of the intensity of surveillance by the State Security, an opposing element.

During the communist regime, the method of collective punishment was dramatic. So, if someone committed a “crime” or expressed opposition to the regime, he was not the only one who would pay the consequences, his relatives also suffered. That is why in the reports found in the archive, they talk about his close people.

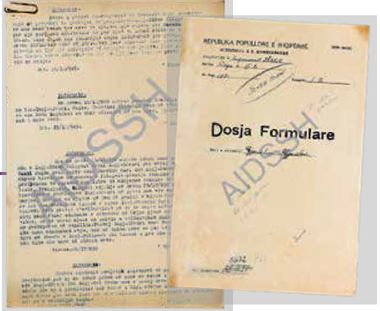

The engineer’s observation becomes even clearer, in some sheets next to the AIDSSH file, which bear the title; “Different informative summaries of Gjovalin Gjadri”. These sheets always start at the top with the words; “Death to Fascism – Freedom to the People”. We have over 30 pieces of information, which are, in a way, various spies on every action of Gjadri, by individuals with pseudonyms. We have these spies from different dates, from 1946 to 1954.

Following personalities of science, art or politics has been a distinctive sign of the Albanian communist regime. This fact stemmed from the mistrust that reigned among political leaders. Distrust of intellectuals, distrust of each other, fear of each other. Under the dictatorship, the regime did not believe in the obedience of the people and for this purpose, it organized a continuous control for followers, against everyone, especially against those who could present a danger to the power.

An element that we considered of special anthropological importance, during the analysis of the files, was the use of the word “it is said”, during various denunciations and espionage. This word, being evasive, gives rise to rumours, as it is not clearly defined who is the source of the information. This also has to do with a dual attitude of the government towards the problem of rumours: on the one hand, the regime officially condemns rumours, and the people who deal with them, on the other hand, the regime encourages rumours, “when they are good of power”.

In the Gjadri file, near the Authority for Information on Former State Insurance Files, we often find information with the expressions; “said” and with “anonymous” authorship:

In politics, it is said that his political attitude is not good, but he has shown hatred against the form in […]. It is said that in 1948, he did not carry out the plan and was not hit in front of the collective. It is said that he has cousins in prison, but when he was asked about the verification of his opponents, he stated that no. It turns out that he does not try to benefit from the Soviet experience, but uses German literature. (our emphasis)

This way of obtaining information has supported an unparalleled violence against many innocent people who did not even have the opportunity to defend themselves in the face of accusations; “it is said”, with anonymous authorship. Faced with the question that could be asked by the accused about the authors of the formulation of the charges, the employees of the Security, had the formula ready: “The Party, it knows everything”!

From another piece of information, where Gjadri’s actions at work are commented, we notice how the government often uses conflicts between colleagues, so that they can accuse each other. “Lufi and Gjovalin Gjadri do not get along, because Lufi hands Gjadri work to do, which belongs to his sector and tells him that on this date, he must be ready. Here Gjadri gets irritated and fights with Lufi”. (On 15.03.1948. From section III.).

Inter-human and inter-professional relations in communism were the prey of a mutual fear and of being sued or denouncing opinions that someone could openly express in good faith or in a friendly conversation. Often, quarrels between persons could be used by the regime for its persecutory purposes, to pit personalities from different fields against each other.

Typical of the regime’s reasoning, it has been the duality in judging intellectuals and scientists: “They are capable, but they are not politically good”. The regime required a total dedication of the person to power, professional, political and moral dedication. Outside the regime, there is nothing that can be more important than the regime itself, therefore anyone who does not have this total dedication can be harmful to the regime. “Therefore, this element is a good engineer, but it is abnormal and politically, it does not agree with popular politics.” (Year 1948, pseudonym).

An important anthropological element, which is related to the work of spies, is also related to the obligation that the latter had to account to their superiors, and they often go overboard with their zeal, describing details that are used to create a idea, that the person being watched is really dangerous, even when there is no fact to prove the accusation.

“According to a conversation I had with Ing. Myzafer Dragotin, regarding Ing. Gjadrin, after talking to me about his ingenuity, told me that one day he was talking with Gjadrin, about a project worked on by Ing. Lutfi Strazimiri said: “Ah, the work of this person is also interesting, what crime has this person committed?” Ing. Dragoti did not answer you”. Then he continues: “From looking at his general activity, it turns out that he is a menefregist at work and therefore his work comes out late, not well studied and without any basis of the Soviet system.

Although we do not have concrete facts in our hands, as an opinion, I say for sure that he is a dirty fascist, because although he is paid about 10,800 Lek per month, he is unhappy with the reward he receives. In a political meeting or discussion, such as political information, etc., he does not receive them well, and expresses this in indirect words”. (On 17.01.1951, information under a pseudonym, our emphasis)

This was, in summary, the climate where engineer Gjadri worked and lived for 28 years, whose works have left an extraordinary testimony in the construction sector, of bridges and roads in Albania. For this important figure of Albanian engineering, in 1967, the school that bears his name “Gjovalin Gjadri” was opened in Gjadër in Lezha, as an appreciation for his many years of work.

Gjovalin Gjadri as a writer

Gjovalin Gjadri remains a high personality in his field. In addition, we would like to mention his merits as a writer. In 1941, he lost his wife, Zejnep, whom he loved so much that he immortalized his pain in the book ‘Letter to my dying wife’. The book contains letters written between September 3, 1941 and July 20, 1942. Among them, there are also letters exchanged between lovers, as well as many philosophical reflections on life, death, society, culture.

In reading these letters, you feel as if you have opened the secret diary of a relative. The secret is also confirmed by the publication of this book, which Gjovalin Gjadri publishes in a foreign language, German, ‘Briefe an meine tote frau’, and under the pseudonym; G. Maranaj. It seems like it will keep the reader away from that chaotic time of war. The researcher Ardian Ndreca, who translated the book from German, provides further information in the preface, which complements this book quite well, which is unusual in Albanian literature.

Getting to know Zejnep Toptani happened in the 1930s, she was the daughter of Abdi Toptani, one of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence. Abdi Toptani could not accept his daughter’s marriage with a man who did not belong to his rank and most importantly, a Muslim, who in 1920 was a representative of Sunni Muslims in the Supreme Council, could not accept for a Catholic groom.

But Zejnepi leaves her parents’ house and marries engineer Gjadrin, against the wishes of the family. After building their family and with the birth of their son, Egon Gjadri, Zejnep developed tuberculosis. Despite his great desire to live, on August 15, 1941, he died in Rome.

Among the pains, the author, expressing his pain for the loss of his wife, tries to find the culprits and causes of this loss. Once he sees the fault in himself, once in the war, that they were not given the opportunity to go to Vienna for treatment, once in the family members of Zejnep, he even sees it as a revenge of history against them, finding the fault in his great-grandparents her, “Karlat and Andreat”, who according to him, opened the heart and the door to the Turkish enemy.

The anthropological structure has quite a silent presence in this book, since it is clear that the historical person can never be conceived, separated from the expressive individuality of the subject. Gjovalin Gjadri writes: “I know, you want me to hold my own, to show myself strong in front of people, as the docks of our country demand, as your education and pride demand”!

As we mentioned, there are two dimensions in this pain, loss, death: a completely personal and intimate one and a social dimension, which forgets the individual man – the individual man is forgotten, since when the father has to oppose the marriage between a Muslim woman and a Christians, since the impositions of rank prevent the union between a simple boy and a girl of this kind: a war between fanaticism and civility.

This book has the greatest expressive function in these divisions, which feed a rich anthropological discourse, where the equal sign is set only by love and, therefore, death. Yes, death brings to light the misery of fanatical behavior, the uselessness of human trifles, in the face of an extreme event like death. Here’s how Gjadri reminds his wife in his letter of the concern she had for the brother-sister relationship, already broken precisely because of Zejnep’s choice to marry Gjadri:

“You know, my love, that as far as your brother is concerned, I have never cared about anything, but to calm you down, I will be gentle with him, even though it is difficult, don’t be prejudiced. I had simple, natural thoughts about people’s relationships with each other. I saw his attitude as outdated, incompatible with the education he had received abroad and could not be justified with the pressure that your old father could exert on him. Memorie.al