A Journey and Insight into the Life and Work of Koliqi

One of the most prominent personalities of Albanian letters of the last century

Memorie.al / A special contribution was given by him to education in Kosovo in 1941, when Italo-Albanian forces had penetrated the country and expelled the military and police forces of the infamous Yugoslav Kingdom. During its entire rule from 1913 to 1941, that Kingdom had not allowed a single Albanian school or even a single book in the Albanian language. Those Albanians who studied their language illegally were persecuted and sentenced by the regime to up to 20 years in prison.

The dispatching of more than 200 teachers to Kosovo, and the opening for the first time of hundreds of Albanian schools in Kosovo, Macedonia, and Montenegro, was the greatest gift that could be given to a nation unjustly divided and cruelly persecuted solely because of its national and religious identity.

Regardless of the fact that Koliqi remained loyal to Italy, it cannot be said that he was a loyalist of fascism; indeed, during that time, he helped Albanian intellectuals whom the regime treated as enemies to the best of his ability. After the liberation from Italy, Koliqi was anathematized as a collaborator of the Italo-Albanian regime, and his work was undervalued.

However, Koliqi’s labor and work – his contribution to literature, culture, Albanology, and especially the opening of Albanian schools in Kosovo and beyond – constitute a major contribution that is not diminished by his party affiliation at a specific time. Koliqi deserves a monument in the center of Prizren or Pristina.

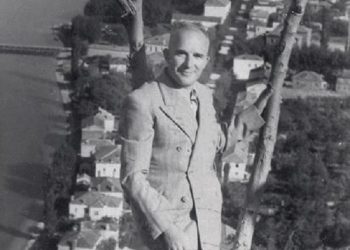

Ernest Koliqi was born in Shkodër on May 20, 1903. He was the son of Shan Koliqi and Age (daughter of Cuk Simoni), a descendant of the Parrucej, a very wealthy Shkodran family. On his father’s side, his origins traced back to the Lotaj of Shala in Dukagjin, who had settled in the Anamali region.

After his initial schooling at the Saverian Jesuit College, his father sent him to study in Italy in 1918 – first at the “Cesare Arici” Jesuit College in Brescia, and later in Bergamo. Along with other students, he started the newspaper “Noi giovani” (“We Youth”), where he published his first poems in Italian.

Upon returning to Albania, as the internal situation stabilized somewhat after the Congress of Lushnja, he mastered the Albanian language. Through his acquaintance with Luigj Gurakuqi, he met many intellectuals of the time. In 1921, a competition for the national anthem was held; Ernest participated with a poem that won first prize, awarded by a jury composed of Gjergj Fishta, Fan Noli, Mit’hat Frashëri, and Luigj Gurakuqi.

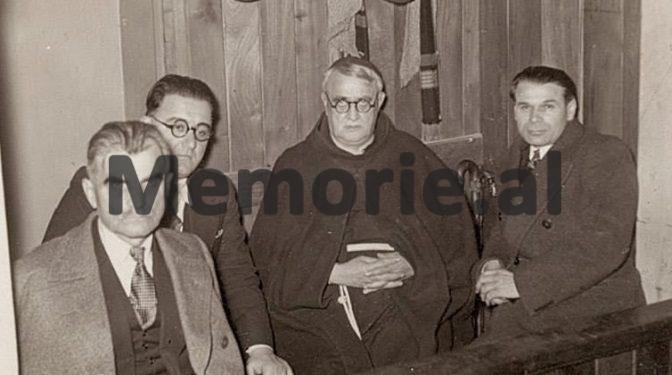

In March-April of that year, representing the “Rozafa” Cultural Society, he participated in a meeting with Father Anton Harapi of the “Bogdani” society, which led to the formation of the “Ora e Maleve” (The Mountain Hour) group. Following the so-called “June Democratic Revolution” in 1924, Luigj Gurakuqi called him to Tirana and appointed him as his personal secretary. Koliqi joined the “Bashkimi” society founded by the deputy Avni Rustemi. Later, he was appointed secretary in the Ministry of Internal Affairs under Colonel Rexhep Shala.

With the “Triumph of Legality” in December 1924, he was forced into exile, moving north to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, where he studied the language and literature of the region. He spent two years in Tuzla, Bosnia, among many highland leaders. By 1928, he was in Bari, Italy, among Bahri Omari, Sotir Peci, Sheh Karbunara, and Kostë Paftali. In Zara, Dalmatia, in 1929, he published his first collection of short stories, alongside his friend in ideals and linguistics, Mustafa Kruja.

Returning to his homeland, he began working as a teacher at the Italian Commercial School in Vlorë and then at the Gymnasium of Shkodër (1930–1933), where his students included Petro Marko and Luigj Radi. He spent his summers in the mountains of Dukagjin, recording “soft songs” (kangët e buta) – erotic folk songs – memories he would later write about in the 1970s under the pseudonym “Hilushi.”

In 1933, he resigned from teaching to begin university studies in Padua, Italy. During 1934 – 1936, he was part of the publishing group for the periodical “Illyria,” where he published the prose poem “Quattuor.” In 1935, encouraged by Koliqi, Migjeni published his famous poem “Të lindet Njeriu” (May the Man be Born) in the same periodical. In 1936, he was appointed Lecturer of Albanian at the Chair of Albanology headed by the linguist Carlo Tagliavini.

In 1937, he received his doctorate in Padua with the thesis “Epica popolare albanese” (Albanian Popular Epic), based on collections made by Father Bernardin Palaj. The thesis was praised by renowned Albanologists such as Norbert Jokl and Maximilian Lambertz. In October 1937, he moved to Rome as an Albanian lecturer. In 1939, the Chair of Albanology was established at the State University of Rome, where Koliqi was appointed as an ordinary professor, a position he held until retirement. His only long interruption was during his tenure as Minister of Education (1939–1941).

Minister of Education in the Vërlaci Government

Despite the circumstances of the Italian occupation, Koliqi utilized his office to its fullest potential. During this time, more Albanian textbooks and books were published than in the entire period from 1912 until then. Key publications included the two-volume “History of Literature: Albanian Writers” and the folklore collection “Visaret e kombit” (Treasures of the Nation), which grew to 14 volumes – a monumental feat for the foundation of folklore studies.

In 1940, together with Mustafa Kruja and Giuseppe (Zef) Valentini, he convened the International Congress of Albanian Studies in Tirana, which gave birth to the Institute of Albanian Studies, the predecessor of today’s Academy of Sciences. He founded and directed the periodical “Shkëndija” (The Spark) in July 1940. In September 1941, he dispatched over 200 ‘Normalist’ teachers toward Kosovo.

In a letter dated October 16, 1941, Koliqi wrote to the Albanian consul in Vienna, Nikollë Rrota, stating he had engaged Norbert Jokl as the organizer of Albania’s libraries with a monthly salary of 600 gold francs – one of many failed attempts to save the esteemed Jewish-Austrian scholar from the Holocaust.

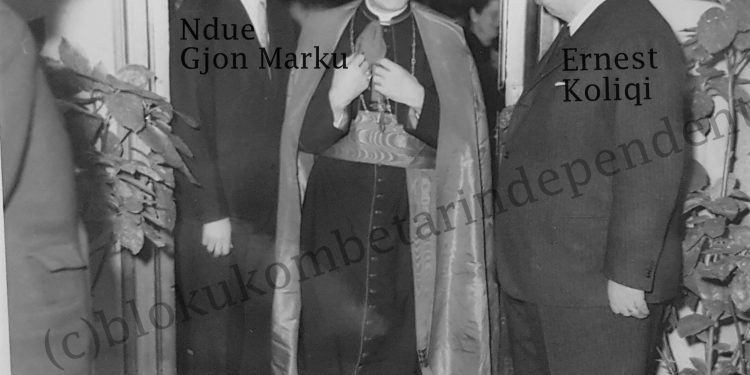

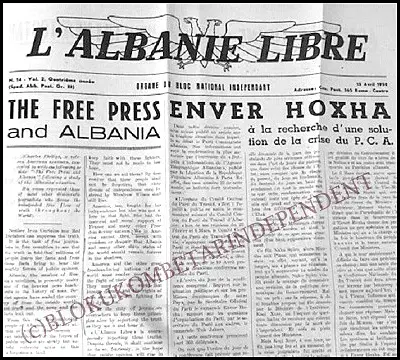

In 1943, Koliqi returned to Rome to continue his university work and was appointed ambassador to the Vatican – the last before the communist regime. Through a phone call, he learned of Petro Marko’s capture by the Germans and managed to save his life. In 1946, he co-founded the “Independent National Bloc” (Blloku Kombëtar Indipendent) party. In 1947, he founded the periodical “L’Albanie Libre,” followed by “Lajmëtari i të Mërguemit.”

In 1957, by decree of the President of Italy, the Chair of Albanian Language and Literature at the University of Rome was elevated to the Institute of Albanian Studies, with Koliqi as its president. He founded the periodical “Shêjzat” (The Pleiades), directing it for 18 years. It became the primary literary-cultural window for the Albanian diaspora, free from the ideology polluting the homeland. He supported many talents who had fled Yugoslavia, including the painter Lin Delija, writers Martin Camaj and F. Karakaçi, and ethnologist Vinçens Malaj.

Koliqi’s wife, Vangjelija, passed away on May 4, 1969. Her loss was irreplaceable and likely hastened his own end. Ernest Koliqi died in his home in Rome on January 15, 1975. He was buried in the Eternal City on January 18, honored by the entire exile community but denied by his own country.

The Works of Koliqi

Koliqi’s literary journey began in Italian, but encouraged by Gurakuqi, he wrote his first dramatic poem, “Kushtrimi i Skanderbegut” (The Call of Scanderbeg), published in Tirana in 1924.

During his first exile, he wrote under the pseudonym “Borizani.” In 1929, he published the collection of twelve novellas “Hija e Maleve” (The Shadow of the Mountains) in Zara. This work reflects the patriarchal, Mediterranean, and Oriental environment of his childhood, infused with a refined Western taste.

In 1932, he published the first volume of the anthology “The Great Poets of Italy,” featuring Dante, Petrarch, Ariosto, and Tasso, with a preface by Fishta. His own poems were collected in “Gjurmat e stinve” (Traces of the Seasons) in 1933, introducing a completely new spirit to Shkodran life.

In 1935, he published “Tregtar flamujsh” (Flag Merchants), a book of 16 novellas analyzing the social and psychological problems of the Shkodran people. His later works, “Pasqyrat e Narçizit” (The Mirrors of Narcissus, 1936) and the novel “Shija e bukës së mbrûme” (The Taste of Leavened Bread, 1960), solidified his reputation as a master of prose and psychological analysis.

Koliqi also published numerous comparative studies, such as “The Two Literary Schools of Shkodër,” and anthologies of Albanian lyric poetry to introduce Albanian authors to a European audience. Until his final years, he worked on translating Gjergj Fishta’s “Lahuta e Malcís” into Italian, leaving behind a legacy of bridging Albanian and European cultures./Memorie.al