From Shkëlqim Abazi

Part twenty-four

Memorie.al / I were born on 23. 12. 1951, in the black month, of the time of mourning, under the blackest communist regime. On September 23, 1968, the sadistic chief investigator, Llambi Gegeni, the vile investigator Shyqyri Çoku, and the brutal prosecutor, Thoma Tutulani, mutilated me at the Department of Internal Affairs in Shkodër, split my head, blinded one eye, and deafened one ear, after breaking several ribs, half of my molar teeth and the thumb of my left hand. On October 23, 1968, they took me to court, where the wretch Faik Minarolli gave me a ten-year political prison sentence. After they cut my sentence in half because I was still a minor, a sixteen-year-old, on November 23, 1968, they took me to the Reps political camp, and from there, on September 23, 1970, to the Spaç camp, where on May 23, 1973, in the revolt of the political prisoners, four martyrs were sentenced to death and executed by firing squad; Pal Zefi, Skënder Daja, Hajri Pashaj and Dervish Bejko.

On June 23, 2013, the Democratic Party lost the elections, a perfectly normal process in the democracy we aspire to. But on October 23, 2013, the General Director of the “Rilindja” government sent order No. 2203, dated 23.10.2013, for; the dismissal from duty of a police employee. So Divine Providence intertwined with the neo-communist Rilindja Providence, and, precisely on the 23rd, I was replaced, no more, no less, by the former operative of the Burrel Prison Sigurimi. What could be more meaningful than that?! The former political prisoner is replaced by the former persecutor!

The Author

SHKËLQIM ABAZI

Continued from the previous issue

R E P S I

Forced labor camp

Memoir

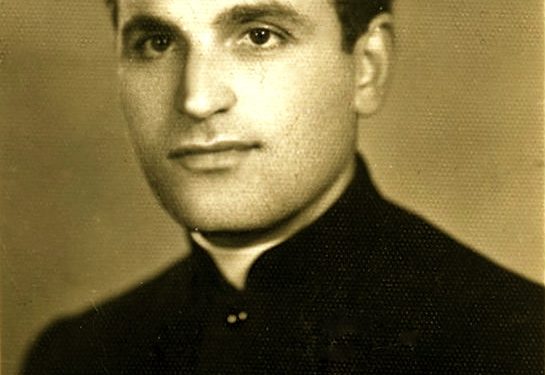

I will mention a conversation between Father Zef Pllumi and Don Mark Hasi, in my presence, after leaving the isolation cell, where I had spent about a month in isolation with the priest: “Fra Zef, with this boy we spent a night tied to the poles,” Don Mark began in his booming voice. “Right there behind the pole, we prayed to the Great God to give us courage. I swear, I felt very weak, I felt like I had brought it upon myself. But God willed it with His Greatness, and we got through this ordeal too!”

“Don Mark, I take this opportunity to thank you for your example of resistance and the courage you gave me,” I interrupted. “If it weren’t for you, I don’t know how I would have spent that night, I might have even begged them to untie me, like that friend before us! You gave me the most excellent moral lesson. I thank you once again!”

“Don Mark,” Father Zef intervened, “this one was introduced to me by my friends; Daut Runa, Sulo Gorica, Esheref Zaimi, and Vaska, before he was put in the cell. Now, since you came out of isolation and spoke to me, I told you that we must protect him. Don Mark, we are very old, we have been sentenced for a long time, and the communists have sworn not to let us get out of here alive. Only a handful of priests are left, whom God has preserved so far, but life has a limit and no one is eternal in this world. What we can do, we must tell, so that they can tell the generations. Listen, boy!” he addressed me.

“Here, there aren’t many choices, there are only two paths: one is long and full of hardship, to study, to study, to study! And the other is easier: to side with the command. Of course, the first path will tire you physically, but it will bring you peace and make you respected among society and friends, only you will serve your sentence to the last day! And the second one will tire you spiritually, it will give you some fleeting pleasures, but it will lock the doors of life for you, and you will still serve your sentence to the last day! So, in both cases, it’s the same thing, but the ending has a characteristic, either a little softer or a little harsher; as a broken slave, or a resilient one. In the end, they reach the same place; either submissive, or in internment; either an overseer, or an overseen one!”

Under the example of these great men, I chose my own path; books, books, and books. A laborious, steep, and very tiring but very alluring path. Once I entered this dance, I immediately forgot the barbed wire, the guards with rifles, the police with batons, the iron handcuffs; I immersed myself in a reality completely different from the one that surrounded me, I felt in harmony with my mind and my soul. That’s when I understood the believers, who pray to face the merciless waves of life more easily.

Thanks to this meaningful world, I managed to survive the communist misery, to overcome the most complicated situations, in prison and outside. Some of my fellow sufferers and peers, who didn’t bother to pursue the calvary, either because they got tired quickly and gave up, or didn’t get into these troubles at all, had to face irreparable consequences, in the long years of prison. Then, some were re-sentenced, others ended up consciously on the barbed wire.

The world of books surrounded me with a kind of immunity that only those who have experienced it can understand. After I gained the trust of that priest, who trusted no one but Jesus Christ, he often talked to me about various topics. I understood his concern; he didn’t want the legacy of his teachers to go to waste. He was fixated on the idea that he would not survive the communist hell, and he wasn’t wrong, he was always undernourished and tormented by a whole collection of diseases. In order not to discourage him, even though I didn’t believe it myself, I kept repeating the refrain: “Father Zef, you will live long and all these things you are telling us, you will have the chance to turn them into works!”

But God willed this prophecy to be fulfilled, for him to live and leave us a legacy of a series of immortal works, such as; “Rrno për me tregue” (Live to tell the tale), “Françeskanët e mëdhenj” (The Great Franciscans), and dozens of philosophical, scientific, theological articles, studies, and papers presented at the most famous universities of the West, where they honored and awarded him with the titles; Professor Doctor Honoris Causa. The friendship, of which I am proud and very grateful, would continue until the journey to eternity of this tribune priest.

At the magnificent requiem mass for his farewell, organized by the Catholic Church in the Cathedral of Shkodër, I would be in the front pews. Also, together with my fellow sufferers, I would be in the front rows, in the endless procession, at his burial at the Convent of Arra e Madhe, where, without religious distinctions, with deep sadness, we escorted the great spiritual leader to his final home. But also many Pharisees, those who during his life caused him so much pain and misfortune, now for show, followed the funeral procession, as if they respected the great dead.

Times changed, and so did the roles. The few survivors who escaped the scythe of death were now seeing their executioners off to the grave. I don’t know if these latter felt any kind of remorse at that moment for the irreparable damage they caused to the people and especially to the Catholics? a very difficult question for me and my prison comrades, especially for the one we were saying our final farewells to. When I saw that endless line of people, with different beliefs, but also opposing political views, I remembered the saying that Father Zef used to repeat when he spoke about sinners and the institution of forgiveness:

“The day will come, when they will come to our graveside, to ask for forgiveness! But will we forgive them? I don’t know, I swear? Now, I will answer them with the words of Jesus: ‘Forgive them, O Lord, for they know not what they do’! And so, in the end, we will forgive them, even though it will be very late, and the forgiveness will not be worth anything to anyone!” and indeed, that wise man knew how to forgive with the same nobility as he knew how to hate. Fortunately, when I was taken to Reps, the political prisons were dominated by nationalist idealists; Ballists and Zogists, a few revisionist deviants and a few, very few, spies and immoral people.

Generally, the intellectuals there were formed in the most famous Western and Eastern schools. But even the uneducated ones, originating from rural areas, had grown up and been educated under the shadow of the hearths and had assimilated the culture of the guest rooms, even though it was archaic, but very beneficial. Without noticing the methodical shortcomings, it was a valuable school for the transmission of the centuries-old Albanian tradition, from generation to generation. Even those who came from the urban working class, despite their truncated education, had inherited the best traditions of the citizenship from which they came.

The old prisoners of the late forties and fifties were still teeming in the prisons at that time and the new prisoners, who would inherit the baton from them, naturally melted into that group. With minimal exceptions, in the political prisons, they brought in and took out people who came from the same tribes and families; so, as soon as a new prisoner arrived, he would find there either his father, another his uncle, a third his brother, someone his cousin, someone his fellow villager or the old friends of the family and ideals. The spies and the immoral ones were in the minority, they felt despised by the honest part, and even the command staff themselves hated them for the role they were assigned; after they exploited them to the maximum, they threw them away like squeezed lemons and then left them to the mercy of their victims.

It often happened that some wretch realized the dead end they had been put in and regretted the moral decay they had suffered; then, under the weight of guilt, they tried to atone for it, as much as the damage they had caused to their fellow sufferers could be atoned for; and when they couldn’t, spiritually crushed, they found the most possible escape route, a conscious jump over the barbed wire, where the hail of “Kalashnikov” bullets mercilessly tore them apart, or ended up hanging themselves on some window grate, in the cells where they had been taken to get a false witness for some newcomer. A part of these unfortunate, morally broken people, filled the psychiatric pavilions where, they either ended up as didactic guinea pigs for the practitioners, but, even if they managed to survive, they came out so pitiful that “they made the stone and wood feel sorry for them”!

After the Spaç revolt, on 21.05.1973, an unprecedented and unheard-of physical and psychological terror was applied in the prisons. Every day dozens of prisoners ended up tied to electric poles and at night, in the isolation cells. But since they could not handle this flow with the number of cells they had, because that was their accommodation capacity, then some of the punished ones, spent the night outside, counting the stars in the firmament. Supposedly to improve the structure, meaning to keep the situation under control, the game of transfers reached its peak, they artificially increased the number of spies and immoral people, whom they brought from other camps, especially those convicted of ordinary crimes.

Police terror turned into state terror and, with the dizzying speed of concentric circles spreading in a pond, it crossed the barbed wire of the prisons and occupied the entire space of the socialist swamp, named Albania. The class struggle, in the likeness of these same concentric circles, also spread within the bosom of the Communist Party itself. Now the herarchs were eating each other’s heads, so a few years later, in prisons you would find more prisoners from the former communist stratum, who had been caught by the “wheel” in the elbow war, within their own kind. The old prisoners, as time went on, were becoming fewer, some as a result of the scythe of death, others after completing their sentences, and were sent to spend their old age in internment. But even those who remained in prison were no longer able to work, so they were gathered in the camps for the elderly in Ballsh, in Zejmen, and later, in Shën-Vasi, where death was wreaking havoc.

According to the testimonies of my friends, who continued to serve their sentences, in these years it became difficult to find friends with whom to openly exchange political opinions or, simply to chat. You were constantly being monitored, in every corner you would find a spy. Re-sentencing became an everyday thing, like bread, so much so that jokes began to circulate, for fun. Here is one of them: “When they asked a prisoner with a five-year sentence; how long were you sentenced? He replies: five! “How much has it become?” “Fifteen!” “And how much do you have left?” “Another twenty-five!” So, only the entry date was known, but not the release date!

One of my friends from those years, Pjetër Arbnori, who had the bad luck to spend close to thirty years in prison, when he got out he would tell me humorously about these tricks: “Brother Çim, you were lucky that you didn’t last long, because even the prison itself was put in prison! To find someone to exchange a few words with, we ended up like in the time of Diogenes, you had to cross the prisons with a candle in your hand!”

But let’s move on to my time and my story. The brigade where I worked had turned into a hiding place for some of the most hated people in the prisons, some scoundrels and cell spies, or mice, as they were contemptuously called. These, since they felt despised and inferior, because the honest ones treated them with disgust and had long since kicked them out, aimed to extend their infected claws over the newly arrived prisoners, whose deeds they did not yet know. Naturally, the camp operative also had an indisputable influence on this immoral behavior, which incited them to corrupt the newcomers, and then depending on the result they achieved, he evaluated and rewarded them, with comfortable jobs and double food rations.

From the first weeks when I started working in the brigade of “gimpy people,” I had the chance to meet one such person. As usual, I went to the coal lines, where the channel was waiting for me. At the end of the corridor, my eye caught a shadow, which moved quickly towards the blacksmith’s shop. For the moment I didn’t pay attention to it, because such shadows usually lurked inside that building. Less than ten minutes later, a crouched ghoul entered the hall where I was working, dressed in brown clothes and rubber sandals. I noticed these details, because the figure blocked the little winter light that was coming through the window dressed with bars. I measured him with my eyes from his rubber sandals, to his sullen face. From the start, I didn’t like this shriveled figure.

“When I passed by the blacksmith’s shop, Qazim gave me this chisel, and told me to give it to you!” a muffled voice grated on my ears. He spoke and his gaze darted around, without focusing anywhere, as if he was looking for some secret to discover. I connected the figure of the ghoul with the grating speech and got the crouched shadow, from a few minutes before. I can’t even explain to myself how this idea was born in my head, but I no longer had any doubt: “This must be the shadow man!” I investigated him carefully; that distracted look and that wretched appearance left a bitter taste in my mouth.

“I don’t need it now!” I replied dryly. “When I need it, I’ll go there myself. Anyway, thank you!” and with my head down I continued the blows with the hammer, to make him understand that the conversation was over. “Hey, are you from Berat, by any chance?” I heard the grating tone muffled. “Yes, why? Is there something wrong?” I replied. “No, man, nothing, but since I’m also from there, I said we should get to know each other, because after all, we’re patriots,” he extended it further.

“Why, are you also from Berat?” I pretended to be interested. “Yes, from Koritza e Lumasit, but I live in Elbasan and I have worked in Vlora, as a navy officer,” I felt an asthmatic breath. “So why were you sentenced? How long were you sentenced for? What neighborhood are you from?” he added, but without waiting for an answer to the first question, he continued with the second, the third, and so on, endless questions. Now the tone took on intimate nuances, as if he wanted to hide behind his own veil.

“Listen, sir, first of all, I was not sentenced, but I was sentenced, and second, wait for the answers to the first question, without asking the second one, because you’ve made a mess of it,” I cut him short. Behind that yellowish appearance, some evil was hiding, but what exactly, only God knew?! “What is this unpleasant person, who is looking for my company? I’ll find out!” I gave myself the task. I felt my mind, changed tactics and entered the game. The interest in getting to know me was obvious. So I told him about myself, about the neighborhood, about the alley where I was born, about the people I grew up with.

“Do you know Enver V., the one who is married to Shega of Ali?” he interrupted me suddenly. Of course I knew him, he had moved in as a roommate with one of my neighbors. “Of course I know him. And who doesn’t know their own alley?” I said vaguely. “He is my first cousin. I have been there many times! If you don’t believe me, I will also show you the garden where they and others had it! I know that neighborhood so well, that I even know the first and last names of the boys in the alley!”

He listed a dozen names of my neighbors, including my older brothers. He spoke with nostalgia about the days he had spent in Berat, just like teenagers, when they brag about the fights of the boys in the neighborhood. He put himself at the epicenter of the stories, giving a primordial role to the attributes of the strong one, of the alley boss. I listened to the nonsense and the past appeared before me and all the acquaintances he mentioned. Meanwhile, I returned to old memories, of my childhood years.

At the edge of my brain, a sequence that I thought had been erased flickered. In the center of the film, a small-statured sailor was moving, in a sky-blue suit, a white hat, with a ribbon tied with the logo of the naval combat navy. Because of the sailor’s suit, the dwarf aroused the curiosity of the neighborhood children. He mixed with us and played soccer, on the sand by the river, whenever he came on leave. Barefoot, in pants and a tank top, as thin as he was, he was no different from us other children, nine or ten years old. Then when he wore the uniform, he looked different, -military clothes left an impression on the conscience of the children, so he could not be easily forgotten.

So, I turned the film back almost ten years, when we jealously looked at the clothes of that dwarf sailor. I made the connection with the moment, this prisoner in dirty brown clothes, just as thin as at that time, if not even more shrunken, aroused pity in me. But the feeling of distrust and the initial disgust were not leaving me. While he was remembering the past, he tried to be harmonious and confidential, but as soon as he touched on the present, he suddenly changed, he became the one from the beginning; his body became crouched, his voice became weak, his tone faded, only his bulging eyeballs moved like a snake’s eyes, when they are detecting their prey, they glowed and some murderous sparks.

This macabre light put a chill in my chest and gave their owner the features of a conspirator. What he was telling seemed unbelievable. He started telling me without being asked, that he had been sentenced for high treason against the homeland, to twenty-two years. Supposedly a group of military men had tried to bring the American Sixth Fleet into our territorial waters, under the command of Rear Admiral Teme Sejko, and other legends like this. Supposedly, they had a plan to overthrow the political system. And to appear as intriguing as possible, he put himself at the epicenter of the group and proudly, boasted about these tricks.

According to his words, this was not a common fabrication of the State Security, but an authentic truth. To be more credible, he swore to me, sometimes on the head of his “only daughter,” other times on his “kids.” Try to figure out if he had only one daughter, or many children. Anyway, what he learned for sure was the truth, about the supposed coup group of Teme Sejko, who agreed to sacrifice himself, in the name of a wicked ideal! He told me about the love of his life, about a plump teacher from Elbasan, whom he had married around the sixties and who after the sentencing, they had made a pact: “A fictitious separation, just to escape the vicissitudes of the class struggle”; always according to him.

He told me about the endless court proceedings, which supposedly were still going on, for almost eight years. – “From time to time, they take me to appear in court, because they have not closed my case. They accuse me of high treason, at least three or four months a year, I am forced to spend in the cells, in special interrogation.” “Man, you must have been very important! I pretended to be surprised. – How could they have left you without putting a bullet in your head, like Teme and his friends”?! “E-e, e-eh…”! – He let out an exclamation, the meaning of which I could not grasp. “But, I didn’t ask you, where do you work?” I teased him ironically. He tried to formulate an answer, but even though he twisted the words, he didn’t come up with anything, so I threw away that little pity that he had previously aroused in me.

The suspicion that this could be, either a spy, or an immoral person, multiplied. Upon reaching this conclusion, I asked him to leave me alone to finish the work. “I see, you are free, while I have to open the channels, otherwise, I will spend the night in the hotel without rent!” I cut him off and started the blows on the chisel. As always in the afternoon in the barrack, I told my neighbors about the meeting and the conversation with my compatriot. “Oh boy, today you have encountered the professor of evil! I swear, he came with an order! To learn the good, you must distinguish the evil! But, to see how far evil goes, you must know its carrier!” old Esheref was enthusiastic.

“I don’t know him well, but it’s better to talk to Sulo, as a man from Berat!” Vaska distanced himself, then: “Do you know what you have to do, it’s better to look at books, they don’t bother anyone!” “Oh Vask, don’t stop the boy! To become a professor, you must learn everything! Go, boy, go, buy, but don’t sell!” In the evening roll call, I met Daut Runa and Sulo Frrica. I told them what happened to me.

Old Dauti cut me off: “Stay away from that spy! Yes, he is a State Security informant, don’t go near him! Ever since he came to prison, he has only wandered from cell to cell!” he finished and said nothing more. While Sulo, as was his custom, took off his glasses, wiped them well, cleared his throat and thundered: “Oh, oh, what a spy! The shame of all of Berat! Yes, he is our shame too, that ill-mannered one, because he is from our side!

But he is a coward; in fact, he is more of a coward than a spy! One day, they will find him dead from fear, like a rabbit in the briars! But, by God, I know him well! Oh, how much he has betrayed, that stinker! The government has sentenced him to prison; God has sentenced him to loneliness! God’s punishment is heavier than the government’s, my son! Stay far away, don’t give him any conversation, those types don’t leave anyone without gossiping, just to make themselves look clean!” Memorie.al