By Agron Tufa

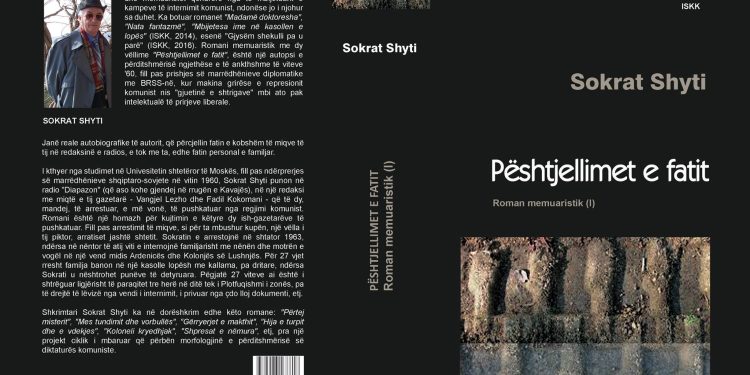

Memorie.al / Writer Sokrat Shyti is the “great unknown” who has just revealed the tip of the iceberg of his literary creativity. I say this based on the limited number of his published books in recent years, primarily the voluminous novel “Nata fantazmë” (Phantom Night) (Tirana 2014). The novels: “BEYOND MYSTERY,” “BETWEEN TEMPTATION AND WHIRLPOOL,” “THE DIGGING OF ANGUISH,” “THE SHADOW OF SHAME AND DEATH,” “COLONEL KRYEDHJAK,” “THE RUSTED HOPES,” “THE CONFUSIONS OF FATE” I, II, and other works, all novels of 350 – 550 pages, are in manuscript form waiting to be published. The dreams and initial enthusiasm of the young novelist, who returned from studies abroad full of energy and love for art and literature, were cut short early by the brutal edge of the communist dictatorship.

But Sokrat Shyti, it seems, belongs to that breed of writers who do not succumb and do not surrender. The old dream of writing was kept hidden and suppressed beneath the skin, a spirit that knows well that dictatorships are nomadic, however absurd and brutal they may be, and that their nomadic character cannot triumph over the essence of the writer, which is eternal, at least enough to write the obituary of the dictatorship.

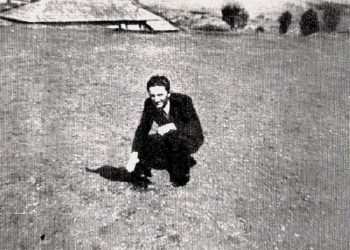

This has always happened, and it happened with Sokrat Shyti too. Exiled to a “bermuda triangle” of a lost province, he emerged alive after 27-30 years and began to rise from the ashes.

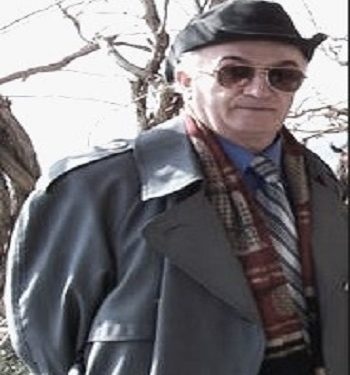

But who is Sokrat Shyti?

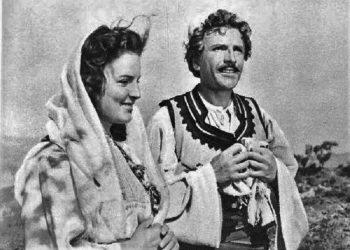

Let’s give a quick snapshot portrait, unable to create a complete portrait since his life is such that it cannot be captured in a note like this.

Returned from studies at the State University of Moscow shortly after the break in Albanian-Soviet relations in 1960, Sokrat Shyti worked at Radio “Diapazon” (which at that time was located on Kavajë Street), in an editorial office with his journalist friends – Vangjel Lezho and Fadil Kokomani – both of whom were later arrested and subsequently executed by the communist regime. Besides the radio, 21-year-old Sokrat, if we imagine him, had passionate literary interests at that time.

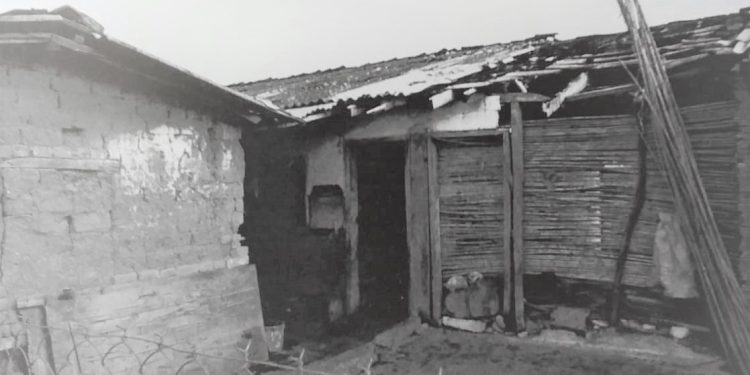

He wrote his first novel “Madam Doktoresha” and was on the verge of publication, but… alas! Shortly after the arrest of his friends, to fill the cup, a brother of his, a painter, escapes abroad. Sokrat was arrested in September 1963, and in November of that year, he and his family (with his mother and younger sister) were interned in a place between Ardenica and Kolonje of Lushnja.

For 27 consecutive years, the family lived in a straw hut without windows, while Sokrat was subjected to forced labor. Throughout those 27 years, he was legally compelled to report three times a day to the local authority. He had no right to leave the place of internment and was deprived of any kind of documentation, etc. In these conditions, amidst a cowshed, he raised his children.

After the fall of communism, he continued to stay for three more years in that place of suffering, and only in 1993, when his two children were of school age, did he manage to move without notice to Tirana, where together with 9 other families of political prisoners, the then government housed them in the former kindergarten no. 9. After the year 2000, with great struggles, and thanks to the help of his supporters, Sokrat Shyti managed to publish a small number of books in limited print and simple binding—just a tiny portion of his creativity.

The novel “Nata fantazmë” by Sokrat Shyti…

I can say that no Albanian novel to date has managed to touch so kaleidoscopically upon the layers of Albanian reality during the time of dictatorship. Against a backdrop saturated with great political intrigues of imperial dimensions, in a microcosm of the world, the “little man,” the “superfluous man,” breathes and trembles, his fate tumbling from one political demigod to another.

However, life, the daily reality configured amidst wild pressures and machinery, the hypertrophied fates that crash from anxiety to anxiety, under the watchful eye of dictatorship, has found its authentic expression in hundreds of pages of the novel “Nata fantazmë.” Within the pages of the novel, the clutches and paralysis of these small people’s fates are felt, just as the tremors of directors, bosses, and ministers are felt: no one is secure in their fate or existence. The plans of the novel are broad, of a Tolstoyan type, but the world, the emotional psyche, the complexes, and the metaphysical experiences of the characters populating the novel resonate with Dostoevskyan spirit.

In terms of scope and sensitivity, the novel “Nata fantazmë” can be called all-encompassing since it encompasses and touches all layers of Albanian society, from the jevga, the police, the butcher, the fishmonger, to mid-level and high-ranking party and state officials, political secretaries, and ministers, including the chairman of parliament, who only feel the betrayal when they sense it in the blood’s current, experiencing within themselves the most bitter disappointment, yet they find it impossible to reduce the gluttony of malice.

On the other hand, everyone seeks to justify their existence, everyone wants to express their truth, everyone seeks support from someone stronger, so as not to be discarded by the iron aggregate and leveling nature of dictatorship. And everything has a price: some pay for dependency, submission, weakness with the surrender of honor and personality, while others pay for courage with their lives: in a world where mercy does not exist, one must invent the weapon of survival.

The writer gives everyone, regardless of rank or position in the social hierarchy, the opportunity to discover what they represent, what keeps them alive. Some are kept alive by challenge and arrogance, others by cunning, intrigue, and servility, while others are kept alive by fear, like Corporal Bakiu, who uses his fear—the fainting—as a weapon of survival. By the way, the entire novel pulsates with fear, with various kinds of anxiety and dread. Fear can be said to be the main character that builds the powerful emotional poles of the work.

The fates of people are set against a backdrop saturated with insecurity and terror: they are alive today, tomorrow they may stand before a firing squad, often without knowing why they are being executed. We are at the peak of terror and insecurity: the communist state commits bloody massacres against intellectuals to demonstrate their submission and servility to Stalin. This is artistically conveyed in the center of the novel through the Albanian “St. Bartholomew” which begins with the throwing of a quantity of dynamite at the Soviet embassy.

Throughout the night, hundreds of intellectuals are arrested, and 22 of the most prominent are executed. With this bloodbath, Stalin is satisfied, and the security of our state’s brutes is guaranteed. What remains is the bitter, tragic taste of fate, not just that of the executed, but the fate of their families.

However, in this chaos, other characters intertwine, from the simplest of people to the chief of cabinet to the minister of state, who, as a woman with gentle sensitivity, becomes a conduit for the inner voice, entering the hellish cell of the victim, the surgical professor, husband of her friend, not merely to console him before his execution, but to create a bridge between him and his wife, to take with him the last testament that he may free the poor woman from the loneliness of widowhood for the years to come.

The language of the characters is given appropriately, in accordance with human and social vocalization, often paradoxical, with passages of dark humor, absurd logic, and sarcasm. The rhetorical characteristics retain the ambient coloring but also reflect the level of cultural and social belonging of the characters.

The novel “Nata fantazmë” is primarily written in the realistic tradition, draining the frames of our social and political realities, which for fifty years remained orphaned, unexperienced by the “party writers” and the dominating dogma of “socialist realism.”

The novel by Sokrat Shyti elevates these realities to be re-experienced, returning to that time a part of our moral debt and emphasizing that nothing is forgotten. It is a deeply human novel, conveying a message and spirit, while the polarized and artistically homogenized worlds bring to Albanian literature an essential contribution in the language and sensitivity of the narrative style.

The appreciation of this novel, in addition to its undeniable literary values, is a recognition and gesture that, although delayed, should unite us around the act of human resistance, resistance against evil and the survival of both man and literature. Is it not a miracle that all these human and artistic virtues have survived intact in the man and writer Sokrat Shyti?/Memorie.al