Part One

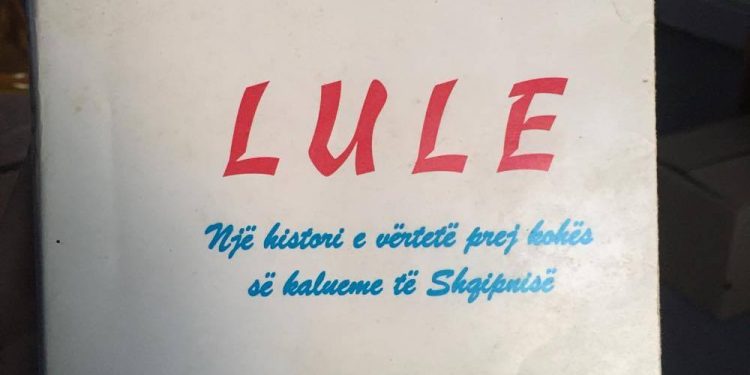

Memorie.al / “My Albanian Diary” by the Austrian parish priest, Fabian Barcata, is published for the first time in Albanian by the “Mirdita” Publishing House, on his centenary. It was written in 1905-1906, in Kryezez (Rubik) and was published twenty years later in the Franciscan magazine “Franzisziglöcklein”, Austria, in 1926 – 1927. This is the first genuine diary of a foreign priest for Albania. The name of Fabian Barcata, this Austrian mystic from the beginning of the last century, is almost unknown to today’s reader. This was the case seventy years ago, until his book “Lule” was translated and published in Albanian, thanks to the care of Professor Karl Gurakuqi, one of the most prominent names in Albanian literature and culture, who died in Rome as a political emigrant in 1971.

The work was well received, and the author, who must have been very happy about the publication of his book in Albanian, gained fame. However, the work and the author “lost” again in the smoke of half a century, remaining “little known”, although not because of him.

In fact, even years later, Barcata was almost “lost”, even though rumors circulated about him, especially among folklore collectors, who had been fascinated by a dance, “Pëllumbesha dhe Skifteri”, that a foreign parish priest had once described. After the 1990s, Austrian missionaries again invaded Albania, and many of them settled in the northern regions, just like their predecessors, 100 years ago. A well-known Mirditorian scholar, Ndue Dedaj, made the first contacts with them, while in the first conversations between friends; “Barcata” was occupying a central place.

Dedaj, says that “for 20 years I had heard from old people in Rubik, that a book had been written about this place, while digging in the National Library, where he found the only original copy of the novel “Flowers”, published in 1924 in German, several copies came to Albania, then a reprint in five foreign languages, five years later, while it was published in 1930, by the Publishing House “Nikaj”, translated into Albanian by Prof. Karl Gurakuqi.

In 2001, after a reworking, the long-awaited novel “Flowers”, by Fabian Barcata, was reprinted in Albania by the Publishing House “Mirdita” in 2001, where some data and authentic photos are provided, while later further data were requested in Austria, to complete his unusual portrait. Thus, in March of this year, more complete data on this enigmatic figure, and especially his original work, are coming to be published sought-after and much-welcomed “My Albanian Diary”, compiled in the latest book by author Ndue Dedaj: “Fabian Barcata and his Albanian Diary”.

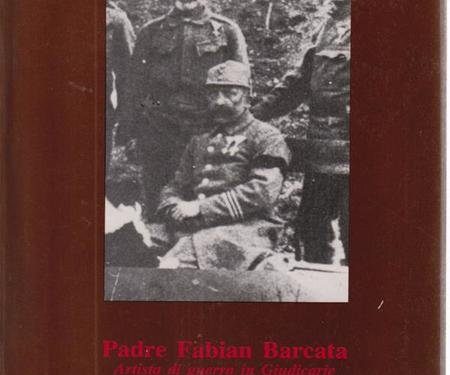

Passport: Who was Fabian Barcata?

Barcata was born in the diocese of Trento (Valfloriana) on March 29, 1868 and was baptized with the name Moritz, being the first in a family of 15 children. Already in childhood, his precious gifts appeared, such as artistic inclination and talent, humor and subtle irony, which distinguish Austrians. On August 25, 1885, Moritz Barcata, together with seven other students, took off his secular skirt in Pupping and took on the habit of Saint Francis instead. Thus, Moritz became Father Fabian.

He was ordained a priest on May 3, 1891 in Brixen and thus began his priestly activity. He was appointed in Graz. More in 1893 he was transferred as a lecturer for Albanian clergy in Lankowitz, where he remained until August 6, 1894. There he also helped to reorganize the monastery library. In 1894 he worked again in Graz as a lecturer for high school subjects. Father Fabiani was the last of the Franciscan fathers to settle in Styria.

He lived for a long time among the Albanian highlanders, mainly in the region of Mirdita, lecturer of the Novitiate and parish priest of Kryezez (Rubik). As a man endowed with special gifts and qualities, Barcata, a Franciscan missionary and prominent writer, became closely acquainted with the local customs and traditions. In order to enter the spirit and world of the people of this country, he learned the Albanian language.

The most notable years in the life of Father Fabiani were the years of his stay in Albania, where he came twice in 1895 and 1899 until 1907. His work as a missionary among a people with a harsh, but strong and deeply religious nature, awakened the best feelings of Barcata.

The Franciscan missionary stayed in Kryezes (Rubik) of Mirdita in 1895, for two years and then from 1899 to 1907, he spent some time in Shkodra. Threatened by malaria, he returned to his homeland in 1907. He died in 1954, at the age of 86.

Portrait of an unusual man

In August 1906, the Austrian engineer, Karl Steinmetz, (after making a brief visit to the church of Vela, a simple, unadorned building, where Dom Mark Negri received him in a friendly manner, as was the custom of the Catholic clergy of Northern Albania) arrived at the parish of Kryezez. The missionary’s unusual appearance appeared before him, as he described it: “Extremely long mustaches, of which any pirate officer would be proud, shadowed his mouth, where a short pipe was placed.

A worn-out hat covered his head, and only his faded Franciscan habit showed who the man was. He was Father Fabian Barcata, a Tyrolean who had been working in Albania for several years. The venerable gentleman immediately prepared lunch for us with his own hands, which we ate in the courtyard under the shade, enjoying the presence of another Austrian, a young clergyman who happened to be a friend of the missionary.”

This portrait and “snapshot” testimony of the Austrian scholar Steinmetz about Barcata directly from his temple, the Franciscan Congregation of Rubik, is of particular interest for the details with which he describes it. “Father Fabian, a true Tyrolean, honest and sincere, who shares everything he has with his believers, possesses a wide culture, especially in the natural sciences and is quite prepared. Every stone and every plant is known to him in the region. The sick come from far away to seek the help of the parish priest of Kryezez, who carries out a useful medical activity thanks to his knowledge and a rich reserve of medicines.”

Interview with researcher Ndue Dedaj, about Father Fabian Barcata

The renowned researcher Ndue Dedaj, who for 15 years has been studying the figure of an Austrian mystic who lived in Kryezez, Mirdita, at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, introduces us to his unknown history in this interview.

Mr. Dedaj, it seems that you are closely connected to Fabian Barcata, why?

It was unimaginable to “meet” him after 100 years. He is a rare humanist, hardly anyone has stepped foot in this country in the way he lived, acted, researched, and studied in detail the life of the highlanders here 100 years ago. Fabian Barcata appears to us as a rare interpreter of the spirit and mentality of the Northern Albanians, of the customs, rites, superstitions, traditions, and virtue of the people of this country, with whom he merged like a rare foreigner. He was a friar and a writer, an artist and a scholar, but also a healer. A surprising figure for European humanists.

He left one day, but he took Mirdita with him under his indomitable Franciscan mantle. Kryezezi always slept and woke up in his conscience, like a never-completed hostage, because of the human images, the memory of which could never be extinguished in him. He left to return after a hundred years, as if from a wandering legend, always “the messenger of every blessed word”, as his Franciscan brothers of the monastery of Schwaz and Hali called him.

He came to Albania to preach the gospel, but also to heal people from diseases and superstitions, to enrich them spiritually. But he also took for himself the kindness of these people, as he says many times in his diary. They gave him the strength and the wonder to better understand the boundless world of man. At the same time, he could not stand without carrying out his mission to the end as a writer, namely to write and publish their stories “From the past times of Albania”, interwoven in “Old Laws and Customs in the Albanian Mountains.”

Mentioning “The Broken Kumbona”, “The Blood of the Forgiven” and especially “Flowers” by Father Fabian Barcatte, the renowned historian, academician Zef Mirdita (Zagreb) considers these works “important for the knowledge of customs among the Mirdita people”.

Barcatte, the little-known author of a well-known work, the novel “Flowers”, after once shining like a meteor in the literary and cultural sky of the 1930s, would fade away for decades. His creative bibliography is supplemented with “My Albanian Diary”, novels, stories, works in sculpture, painting, museums, everywhere in the temples of St. Francis, etc. His hand, as a talented master, decorated the monasteries of Austria, and the churches of America, and those of Rubik and Kallmet in Albania.

In what Barcata writes, it seems that he found his Tyrol more than anywhere else in the upper background of the gray mountains, is this reason why he loved this place so much?

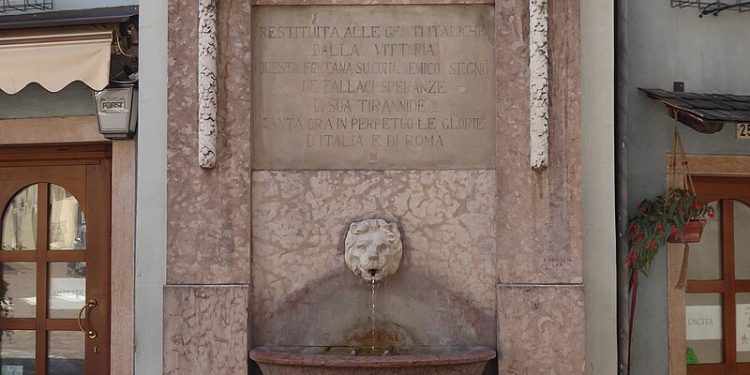

It is true, as soon as he set foot in the regions of Mirdita or Shkodra, the mountains of this place resembled the high mountains of Tyrol, his birthplace, which he loved so much and which he missed so much when its “hours” came… Tyrol, this picturesque place, with alpine-style dwellings, was not unknown to Albanians in the past, when they studied in Innsbruck, the largest Austrian city at the foot of the Alps, but also after the 1990s, when students went there again, etc.

Even when Barcata had died and his “Flower” had wandered as a work in the wind of time, among the sons or grandsons of the inhabitants of Kryezez and Bulgër, an old friar was often mentioned, who had written “Rubik’s Flower”. This is how they had recently “named” the novel they had heard about, but which they did not know, which was neither permitted nor forbidden; but when Albanian priest writers were no longer published, how could a foreigner be republished, when the translator of the book, Karl Gurakuqi, was a political émigré, and moreover: the old spirit of the novel did not coincide with the new spirit of the communist regime.

There is a message from Barcata about the “world citizenship” of that time. In fact, what distinguishes Barcata from other foreign travel writers?

Fabian Barcata, the friar from South Tyrol, came to Northern Albania after many Catholic missionaries, scholars and foreign travel writers. Except he did not come as a visitor, like most of them, like the apostolic visitors of the Vatican, Štjefen Gaspri (1676), Vincenc Zmajevič (1702) etc., nor like the French, Austro-Hungarian consuls, who mostly stayed in Shkodra and occasionally undertook visits to the northern or southern regions. Barcata came to live here, at the turn of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

After having lived the life of the mountains, after having discovered a special world in its Olympic tranquility, after having finally discovered the troubled “soul” of this country, through his novel “Flowers”, he addresses the Europeans, as if with the tongue of a bell: “Here, here, in Albania, must come all your educators of the people, starting from the university professors, who do not see beyond their own noses, to the proud classes of teachers, who occupy the places in the popular schools with the name of humanity; here, in Albania, must come your demagogues and your philistines, all the anarchists of your countries, communists and socialists, your craftsmen and workers, citizens and peasants, all the dissatisfied elements, great and small.

Here, yes, next to this simple and incorruptible people, to these people, whom they call semi-barbarians, must come come to school and learn, how in poverty, in the simplicity of the places, in hope in the great God, the happiness of every man, in particular, and the joy and well-being of peoples in general, has flourished. Here in Albania, they would all find the true high school of life”.

What are the connections between the monumental church of Shelbuem of Rubiku and Barcata?

As a historical church, Shelbuem of Rubiku, had always kept in the body and apse, traces of its early age, inscriptions on the walls or bells, dates of events related to it. These had reached Father Fabian Barcata. He draws the attention of the visitor, K. Steinmetz, in the year 1472, to the apse of the chapel adorned with very important frescoes of the church of Rubiku, a major monument of the Albanian Middle Ages. There was also an inscription carved on a Rubik’s cube by Father Shtjefen Gjecov at the beginning of the 20th century, when he collected documents and wrote a literary work.

Rubik continued to collect well-known figures of the church and culture. Father Gjergj Fishta would build the apse of the church and would write fragments of his tragedy “Judas Maccabees”. The great Franciscan scholar, ethnologist and folklorist Father Bernardin Palaj served in Rubik’s Shelbuem until his shocking end. And so did the painter Father Leon Kabashi, until 1967, who had artistically painted the chapels of Shkodra. From Rubik came one of the first poets of the Renaissance, the cultivated and brave priest, Monsignor Prend Doçi, who set off on a long journey around the world, building the abbey of Oroshi. Doçi is the model of the Albanian who brought civilization to the mountains. On the heights of the Holy Mountain, Edith Durham found him and painted him a brilliant portrait, nobler than the lords of England.

From this valley of Fani, Pashko Vasa emerged, along with his unique formula of Albanianism; “The Albanian’s religion is Albanianism”, to tell the world the truth about Albania and Albanians, to be somewhere far from his land and a diplomat and governor. Rubik’s great Redeemer, documented for nine hundred years, was the temple of the little brothers of Saint Francis, who is believed to have set foot in Lezha (1221) to plant the pine tree that would be known by his name. The frescoes, the murals, would bear the traces of a great medieval art.

You have noted that you decided to bring back this character, Barcata, because he is a writer of a special nature. Where does this consist?

Where is Lula, Marku, Pal Gjoka, Shtriga e Mullirit, Dom Doda? Barcata would not be able to climb to Qafë i Fikut, nor cross that path of Molungu, to save Lula, her purity of virtue, since “Lula” has changed so much in these hundred years!? His and Father Anastazi’s fear that the diseases of modern times were affecting the man of Europe, as bad news, reached the place where man had remained man until then! Lula indeed became a teacher, a doctor, an agronomist, but she also became a “commissar”, a refugee, a prostitute…! So, would his monumental call be right: “Here, here, in Albania…”, one of the most monumental refrains that could have been uttered for this country in a hundred years.

Where are the living “characters” of his Albanian diary, the first diary of a foreigner that we know of? However, Barcata comes again with a sacred mission: to show the people of this time what Albania was like in the past. The lines of his diary tell us a part of that sad but realistic chronicle. Barcata, along with us, was also brought back by his descendants a hundred years later. Franz Winsauer, an Austrian Catholic missionary from Vorarlberg, has made a comprehensive contribution to Mirdita, since 1993, when he began his humanitarian activity within the framework of Caritas, but also in this book, translated with great precision by the German translator, Angjelina Luka.

In your publication, the main place is occupied by Barcata’s diary, how did it seem to you?

Fabian Barcata’s “Albanian Diary” is unknown to the Albanian reader. Its publication in Albanian is only possible today, after a hundred years from the time it was written. The detailed description of the people, their poverty, diseases, superstitions, but also their character and virtues constitute its original subject matter.

It joins the ranks of books and writings by foreigners that enrich Albanian knowledge and understanding, which in the last fifteen years have been numerous and welcome. Previously, there were a lack of authentic written sources about Albania, and this diary, although short, is one of them. Going to the sources is always interesting and necessary in the field of knowledge.

The recognition of Albania at that time by foreigners was also important for the creation of the Albanian state in 1912 and the acceleration of the end of the Ottoman Empire. The Albanian image of the early 20th century was certainly not only the idealism of Naim Frashëri’s romantic poetics nor only that of Pashko Vasa’s “Albania on its head in ashes”. Albania was beautiful, yet primitive, loyal, yet dangerous, the Albanian was magnificent in virtue, yet a little flawed in vices, etc.

“Flowers” and “Albanian Diary” will remain among the sought-after testimonies for the Albania of that time, due to the deep and comprehensive knowledge of man, psychology, docks by the author who lived for a long time among the Mirditori, etc., for the humanist spirit that characterizes them as works, as well as for the profile of Barcata as an artist, who skillfully describes circumstances, episodes, human characters, etc.

The diary takes the reader through a chronicle, often sad, full of vital details, events, stories and superstitions, introducing him to poor and reserved people, who, however, have not lost hope and the meaning of life. It resembles a “register”, where everything that constitutes the life of Kryezez in the slums, where there are frequent deaths and epidemics threaten, is notarized.

Most died from the lack of a doctor, medicine and health care, where the priest, found as if surrounded by such a situation, had to provide solutions for everything, so much so that he surprises you when he says that in the room of the deceased I made the decision to become a doctor myself.

Nothing related to the fate of his parish is foreign to him. Often, the friars and nuns also did the work of the doctor and nurse, like the nuns of Kalmeti, also Austrian. This brings to mind the unique example of the friar of the pashalars of Shkodra, Father Erasmo Balneo, so masterfully portrayed by Father Zef Pllumi, in one of his recent books.

Although he lived longer than Migjeni, doesn’t it seem to you that the sick parish priest resembles our Migjeni a little?

Even more admiration for this exemplary missionary of spirituality increases when you consider that he wrote the lines of his Albanian diary while suffering from malarial fever himself, with trembling hands. But faith in God, his sound education, his sense of truth, his philosophy of sacrifice and suffering, his challenge to evil and misery that he had turned into purpose and consciousness, made him impartial in his mission and writings, fair in his judgments, knowledgeable of the environment, customs and rites, a rare draughtsman of temperaments, not dominated in any line by the emotions of the moment.

There is no cry or scream in the pages written by him, no sign of loss of hope and faith, and even though life at that time was itself a cry. He was both director and actor in the dramas and sorrows of the people of Kryezez with whom he lived. Just like our Migjeni, thirty years later, at the time of a new Albanian consciousness, who would convey to the highlanders through their recital the scream and song of proud pain, being threatened by a disease, much more treacherous than Barcata’s malaria, and if lung disease cut him off at the age of 27, this old apostle could not stop him in his 86 years of bohemian life. It is a happy occasion to now read the pages of this diary to the reader in Albanian.

With so much that has been published, can it be called a “completed file” on Barcata?

Absolutely not, you must tear Barcata apart to discover it to the end. For the well-known – little-known work. For the unknown work. For his long-lasting profile as a humanist, missionary, artist, anti-fascist. Because you have a conviction that this life deserves to be exposed, especially since here he became more Albanian than the Albanian. He left a trace, which would be followed after nearly a hundred years, which means that he had not stopped communicating.

At the very least, he would deserve a bouquet of flowers at his grave in the monastery of Schwaz (Austria), from any Albanian who could place it there. But also a bust in Rubik’s Cube, right there on the white cliff, perhaps in the decor of a “dance”, where a dove and a falcon move ceaselessly. He was a master of monuments, busts, even though he never thought about his own bust. A sculptor would have to deal with his original figure, where time had molded one of the strange characters of the 20th century that stepped into Albania. / Memorie.al