Part twenty-three

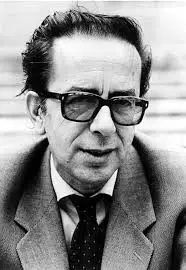

Memorie.al / Exactly 43 years ago, on the morning of December 18, 1981, the Albanian Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu, who had held that position since 1953, was found dead in his bedroom (according to the official version, from a bullet from a pistol) in the villa where he lived with his family, at the entrance of the “Block” of the high leadership of the Albanian Party of Labor, just a few meters from the building of the Central Committee of the Albanian Party of Labor and also from Enver Hoxha’s villa. Although more than four decades have passed since that day, considered one of the most serious and notorious events of that regime, there is still no clear and accurate version regarding what happened to the former Albanian Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu on the night leading to December 18, 1981! However, even after the 1990s, dozens of testimonies and archival documents have been made public regarding that event, “the murder or suicide of Mehmet Shehu,” which continues to be the subject of numerous debates and discussions, even wrapping it further in mystery around the truth.

Based on this fact, in the context of publishing dozens of testimonies and files with archival documents from the secret fund of the former State Security and the Ministry of Internal Affairs, or the Central Committee of the Albanian Party of Labor, which we have published over the decades since the collapse of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime and his successor, Ramiz Alia, Memorie.al has secured the voluminous file “of the enemy Mehmet Shehu,” which has been extracted from the secret fund of the former State Security at the Ministry of Internal Affairs (now part of the fund of the Authority for Information on the Documents of the former State Security), where, with a few minor exceptions, most of them have never seen the light of publication and are made public for the first time in full.

In the mentioned file, there are the relevant facsimiles, the expert report of the investigative-operational group that was set up immediately on the morning of December 18, 1981, led by Koço Josifi (head of the Investigative Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Tirana), the forensic doctors Dr. Fatos Hartito and Docent Bashkim Çuberi, the prime minister’s doctors, Milto Kostaqi and Llesh Rroku, as well as the criminalist expert from the Central Criminalistic Laboratory of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Estref Myftari, assisted by high officials of that ministry, Xhule Çiraku, Elham Gjika, and Lahedin Bardhi.

Also, in the voluminous file that we are making public, there are testimonies from the family members of former Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu, from the service personnel, and his escort group, as well as from all other individuals who were summoned and testified about that event. Moreover, the documents in question, which we are publishing along with the facsimiles and relevant photos, provide more information regarding this matter.

However, even though we are dealing only with archival documents, it should be emphasized that; knowing how that system operated before the ’90s, we cannot claim absolute truth regarding what is written there, as not only from the individuals who provided their testimonies, but also from the investigators of this case, it has been made known that the testimonies were obtained under pressure, intimidation, and physical and psychological violence, with some investigators going so far as to write them themselves while the witnesses or defendants merely signed them.

Continued from the previous issue

ARCHIVAL DOCUMENT WITH THE MINUTES OF THE INTERROGATION OF SAMI MUHAMET PASHAJ, FORMER DIRECTOR OF “ALB-IMPORT,” WHO WAS SERVING A SENTENCE IN UNIT 313 TIRANA, BY INVESTIGATORS OF THE MINISTRY OF INTERNAL AFFAIRS, PELIVAN LUÇI AND LUAN BEGA

MINUTES

(Testimony)

Tirana, May 6, 1983.

We, Pelivan Luçi and Luan Bega, investigators of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, are questioning Sami Pashaj, son of Muhamet and Tajare, born in 1926, in the village of Kremenar in Fier, with a secondary education, convicted once, serving a sentence at Unit 313 Tirana, of Albanian nationality and citizenship.

The investigators warned me about the criminal responsibility I have, for false testimony, under Article 202 of the Penal Code.

The Witness

Sami Muhameti

After being questioned about the matter, the witness declared:

I had a close familial relationship with Feçor Shehu, as well as a very close friendship. Throughout the time we talked together, we continuously discussed various political-social, economic, military issues, etc. The main period we talked was from 1970 to 1974, during which time I worked as the director of the Foreign Trade Enterprise of Albimport.

Regarding the personality and character of the enemy Feçor Shehu, I explain that he was an arrogant, careerist, ambitious person who undervalued others, compared to his own abilities and culture. He was particularly dissatisfied with the duties and roles assigned to him by the Party and the Authority. He thought he deserved to be given higher positions than he had, and for this reason, he occasionally lost control and erupted, either by making comparisons or by speaking ill of other comrades in high positions.

The first hostile conversations from Feçor’s side occurred in 1971. I do not remember the exact time, but it was during the case of condemning a cooperative leader in the Durrës region. During the trial process, it was said that the enemy Beqir Balluku had taken various agricultural products, fruits, vegetables, etc., from time to time. For this issue, I spoke with Feçori, saying that the Party needed to be informed because a person with such a position, like Beqiri at that time, appeared with a name in a trial.

Feçori, after listening to me, said, “There’s no need to concern ourselves with such matters,” and made it clear that he did not like such a conversation. In this case, I saw an answer that did not align with the Party’s orientations, as for any problem, especially one of such importance, the Party and the Central Committee should be informed to take a position, because in this case, a senior cadre with Party and State responsibilities was being discredited.

As is known, in 1973, the plenum of the Central Committee of the Party was held, where the anti-Party views and activities of Fadil Paçrami and Todi Lubonja were condemned. In the hostile conversations I had with the enemy Feçor Shehu, it emerged that he had never agreed with the decisions made at this plenum. Likewise, being influenced by him all the time, I agreed and did not oppose the hostile opinions and conclusions of Feçor Shehu. Thus, during our discussions, he expressed that the views and actions of the enemies Fadil Paçrami and Todi Lubonja were entirely justified.

They were primarily condemned due to the 11th Song Festival in Radio-Television, a festival that not only had nothing to criticize but, on the contrary, brought innovation and progress to our country’s art and culture. The very stages, songs, and their content showed that even in this regard, like in all other countries around the world, we were moving forward. Furthermore, this Festival had been approved from above, and when it came to it, the blame was placed on Fadil and Todi! I remember one instance, which I mentioned to Feçori in conversation, when a Party activity took place in Tirana, the First Secretary of the Tirana Party Committee made a strong discussion, where he criticized Fadil and Todi.

Feçori, after hearing me, said; “They organized this themselves and now are blaming others.” From the discussions we had together with the enemy Feçor Shehu, he opposed the measures taken by the Party at the IV Plenary concerning the education of university youth. Such a thing was naturally accepted by me as well. In one instance, I remember that while we both were walking on the boulevard, the topic of Party measures for the education of university youth came up. During the conversation, Feçori expressed to me that measures should not be taken that would place the youth under strict discipline, as by its very nature, it should not be kept under tutelage, but should be given freedom and the ability to act.

Such an approach was what Fadil Paçrami and Todi Lubonja wanted to adopt, who brought progress in art and culture, something that the youth appreciated. In these discussions, to illustrate his views, Feçori made comparisons between youth in the Soviet Union and Hungary, where youth enjoyed all freedoms of action. Continuing the hostile discussions regarding the education of youth, another topic we discussed was the book by the author Ismail Kadare, “The Great Winter of Loneliness” (first edition).

The conversation revolved around that part of the novel where the author speaks about the “youth of the Rruga e Dibrës” (or “Broduej,” as he expressed). For this, Feçori remarked that; this is precisely the youth of our country, therefore whatever is said in the book about this youth is a true reflection of the reality in our country.

The hostile conversations of this nature, which I mentioned earlier, I also had with Andrea Manço. I became acquainted with him some time ago, around the 1960s, when I returned from Poland. At that time, I was working at Eksport-Al, while Andrea was at Makina-Import. I strengthened my friendship with him, especially when I went on a mission to Italy as a commercial representative and when I returned to Tirana in 1970, where we had time to talk. As with Feçori, I also discussed with Andrea Manço the measures taken by the Party against the anti-Party elements, Fadil Paçrami and Todi Lubonja.

In these conversations, Andrea expressed to me that Todi Lubonja was a quite capable and talented person in his sector. He had made a significant turnaround in the work of Radio-Television. Despite doing a good job there, he was punished for the 11th Festival in Radio-Television, as if he had not been approved from above! We had a conversation of this nature during one instance when Feçor Shehu was also present. When Andrea expressed his dissatisfaction with the Party’s decision to strike against Todi, stating that the penalty was unjust, Feçori remarked, “Sometimes one gets punished for nothing, and sometimes they get punished for a lot!”

Furthermore, on my part, the conversations of a hostile nature, opposing the measures taken by the Party regarding the punishment of Todi Lubonja and Fadil Paçrami at the IV Plenary of the Central Committee of the Party, were also held with Asllan Haka. As I will explain below, Asllan was a person with liberal attitudes and opinions about life. He favored a bourgeois lifestyle. In discussions with him about the 11th Song Festival in Radio-Television, he expressed great enthusiasm and sympathy for it, telling me, “It is a good, beautiful festival that imitates those of the West!”

In the hostile conversations we had with the enemy Feçor Shehu, both he and I did not agree with the measures taken by the Party regarding the revolutionization of life in our People’s Army. At the time these measures were taken by the Party, when the Open Letter from the Central Committee of the Party came out, I was not here. During this period, I was on duty at our embassy in Italy. When I returned in 1970 and afterwards, we continuously discussed this issue with Feçori, and in all cases, particularly Feçori expressed visible dissatisfaction with these measures. I remember well an incident in 1972 or 1973, when we were both walking along the Lana River facing the “Rinia” park.

At that time, some soldiers passed by us, who did not appear very disciplined from an external perspective. It was not like it used to be, where there was strong discipline. Now they do not honor and respect you as before. Now there is liberalism, and this has resulted from the premature removal of ranks. Our army is not in order; since soldiers have been given the right to criticize officers, there is no accountability for the soldiers regarding adherence to rules. For the army to be in order, there must be a strong dictatorship rather than democracy, as it harms it.

In another conversation around this time, Feçori expressed to me that the removal of ranks in our army is a copy from the Chinese. This is not right because the conditions in which we live are different from those in China. In China, due to life conditions, the people and the army obey easily, while we live in Europe, and to have a strong army, there must be dictatorship. Also, regarding the army uniform, Feçori in our conversation told me that it is also a copy from the Chinese and is not suitable for our army. Continuing the hostile discussions about this issue, Feçori expressed to me that the removal of ranks in the army has led to quite negative consequences. The measures taken by the Party for the revolutionization of the army, among other things, also resulted in the removal of certain privileges in the army, which he was not in agreement with.

For this, Feçori also made comparisons with the armies in the countries of the former people’s democracies, specifically with the Soviet Union, where the treatment of the army was entirely different from ours. “Look,” he said, “in the Soviet Union, the army is treated better than any other part of the population. There, even a general, just the salary alone, receives more than a minister, in addition to the other privileges he has. Whereas in our country, they do not have these privileges.”

On another occasion where both Feçori and I did not agree, we opposed the Party’s orientations and measures, including the attack on the group of Beqir Balluku and his comrades.

Feçori was aware of the anti-Party views of Beqir Balluku long before he was targeted. I also informed him about these views. Thus, in a conversation I had with Beqir, where he openly spoke against the Party’s line regarding the army and the tactics that our army should follow in wartime, I also mentioned this to Feçori. This incident, as far as I remember, happened around 1970. One day, I went with my wife, Behare, to visit Beqir at his house. There I found Beqir, his brother Qemali, and his wife. The men stayed outside in the garden talking, while the women went inside.

During the conversation, the topic of national defense came up. Since it had struck me, I told Beqir that I had seen in some places that the shelters and fire stations were very poorly constructed, to the extent that even a light gun could penetrate them, let alone heavy weapons! After listening to me, Beqir said, “We are doing these for nothing because if we are attacked, we should retreat to the mountains, and we will leave the villages and cities with the aim of luring the enemy into the mountains and then defeating them there.” When Beqir said this to me, I asked, “What will we do in the mountains, since there is only brushwood there, what will we eat?!”

Beqir told me that we had taken measures for this; our army was armed, and we had set up farms and auxiliary economies in the mountains that would supply us. To illustrate his views in this regard, he told me that measures had been taken and instructions given to establish auxiliary economies in Lura, Gramoz, Tepelena, etc., that would serve for supplies during the war. I again expressed my disbelief over what Beqir said, telling him that I was unconvinced about such a thing. Beqir responded that we had strategy and tactics, and it was better to retreat to the mountains, draw the enemy closer, and then defeat them. After this conversation, after staying a little longer, my wife and I left.

A day or two later, I met with Feçori and during our conversation, I told him what I had discussed with Beqir. I expressed my surprise to him at what Beqir had told me, even mentioning that I knew the Party’s guidance was that in the event of war, we should not give up any land, let alone leave all territory except the mountains! After listening to me, Feçori said to leave this conversation aside, as Beqir knows this matter better. I recall that this conversation took place around the time Beqir was marrying his daughter, Drita. After this, when the Party had discovered and targeted the anti-Party activities of Beqir Balluku, I remembered this conversation I had and mentioned it to Feçori. However, he quickly dismissed the topic and, visibly shaken, said; “Forget this now and don’t talk about such things!”

In all instances when I discussed the issue of Beqir with Feçori before his targeting, he would say that Beqir was a very competent, capable military figure, a mass leader, and very modest. He tried to elevate Beqir’s image. In another conversation on this matter with Feçori, after the discovery of Beqir Balluku’s anti-Party activities, he expressed his opposition to the measures the Party took to expose him. It was November 1974 when I had to explain myself at the basic Party organization, where they raised the issue of my relationship with Beqir Balluku, explanations that I will detail later, as I have also discussed in previous processes.

During the conversation, in order to make me understand that I was not the only one accountable for the problem of Beqir, he said to me: “Forget that you are not the only one in this situation. Look, at first those from the Central Committee (he referred to the main Party leadership) said they would not lift a finger for Beqiri, while now they want to expand the circle of people, and they are not leaving Beqir to take all the blame. Now, he continued, Petrit Dumja and Hito Çako have also emerged; in a meeting where they were asked about the material referred to as the ‘black material’, Hito said that this material was approved by the Central Committee and that everything was done with the Party’s approval and awareness.

And such a thing is true, Feçori said, because these documents were also found in the safe of Dilaver Poçi at the Central Committee. Continuing the conversation, he kept arguing with me that such a thing was the case, and since it was so, what was being asked of these others when such a thing was required by the Party and the Central Committee?! I remember another instance that best confirms Feçori’s hostile stance against the Party concerning the punishment of Beqir Balluku.

As far as I remember, it was August 1974, and Feçori and I were on vacation at the beach in Durrës, in the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ Rest House. While walking along the shore with Feçori, I asked him what Beqir had done to be removed! In response to my question, he told me: “Beqiri hasn’t done anything, but due to the economic and political difficulties in the country, a sacrifice was needed to justify those, and Beqiri was found for that purpose.” During these conversations, I was fully convinced that Feçori not only did not agree with Beqir’s targeting but considered him a victim!

As I said, these are truths, and after reading this, I sign it. Memorie.al

The Witness The Investigators

Sami Muhametaj Luan Begaj Pelivan Luçi

Continued in the next issue