By Prof. Dr. Aleksandër Meksi

Memorie.al / In our time, numerous essays have seen the light of day, seeking hidden or “forgotten” truths of the past 50 years – history, events, and the people who “made history” during a significant period, from independence until the eve of World War II. It must be acknowledged that many windows have been opened to view this once-forbidden era, when Albanians proved they were both European and learned, capable of transforming their country on the long road from Anatolia to Europe (figuratively speaking), from autocracy to democracy, from regionalism and tribal clientelism to meritocracy, and from backwardness to civilization.

Certainly, not every published book or every expressed judgment is flawless; what matters is that this period is finally being discussed and written about. Time, as always, will be the ultimate just judge of the past. This path must be followed with more knowledge and fewer prejudices, in a more organized and scientific manner, with less amateurism, and primarily based on historical documentation.

I cannot help but notice a lack of interest from scientific institutes and individual researchers regarding this period. Topics from this era and these issues are rarely assigned for genuine research or doctoral dissertations – studies that deserve “citizenship” just as much as those (often fictitious) ones granted in the past, which continue to be regarded even today. Thus, we persist with archaic and outdated methods.

During the dictatorship, many suffered and were persecuted; many were killed, died in prisons, or were interned. Many. An immeasurable number for such a small nation. Among them was a distinct group that endured violence with dignity and stoicism: those persecuted for their faith in God – clergy and believers alike who refused to renounce their religion and their God. They were targeted immediately after the war, but most cruelly after the ill-fated year of 1967.

A place of honor among them is held by Father Zef Pllumi, who, as he says in his work, “lives only to tell” – not for his own sake, as many might, but for others, knowing full well that if forgotten, and the madness of the communist’s risks being repeated. Like many other clerics who emerged alive from Enver Hoxha’s hell, he sought nothing from democracy. Instead, he continued his work as a shepherd of God’s flock, understanding that one must first build the man, and then Albania and democracy.

You do not see them on political platforms; they do not give interviews. They suffer with the people’s suffering, rejoice in their joys, and celebrate alongside them. Father Zef is the last of the true fathers of the Albanian Catholic Church – a generation that, since the creation of the Albanian state and even before, worked unsparingly for a good and progressive Albania. He is the last of a breed even rarer today than yesterday, but one that will surely be recreated by following the teachings and the path of those who survived the past’s absurd violence “in faith.”

Father Zef Pllumi was steadfast in his convictions, but not with mere “Arberian” stubbornness. He never betrayed or denied his beliefs; for this, he suffered and bore upon his shoulders, as a leader of his faith, the heavy cross, accepting martyrdom. He did not become a “flag merchant,” a chameleon, or unprincipled; he remained faithful to Christ the Lord. Padër Zefi, along with his brothers in faith, gave a precious contribution to the rebuilding of the Catholic Church – shattered in its material form, but never in the hearts and faith of the people.

In these difficult years, beneath the simple Franciscan robe, he has remained the same, carrying the heavy weight of years and tribulations. His behavior, his stance, and his voice radiate wisdom, humanism, and a faith that commands respect. You never find him alone, but surrounded by believers, the needy, friends, and students. From him, there is always something to learn, and not just about his faith.

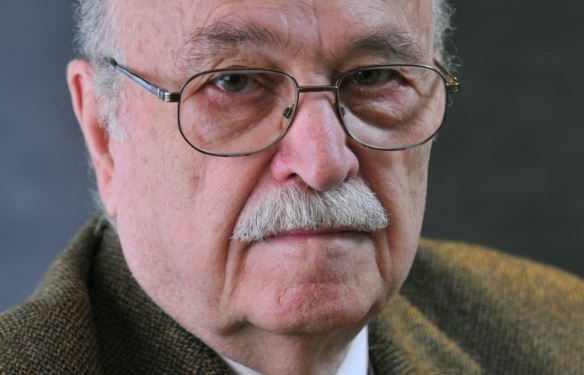

Zef Pllumi is distinguished among us not only for his thought but also for his contribution to Albanian culture. Born in 1924 in Malin e Rencit (Lezhë), he entered the Franciscan College of Shkodër in 1931. There, he followed a classical education under the guidance of prominent national cultural figures such as Father Gjergj Fishta, Pater Anton Harapi, At Gjon Shllaku, and others, mastering several foreign languages.

During 1943–1944, he was the youngest collaborator of the magazine “Hylli i Dritës” and the personal secretary of Pater Anton Harapi. In late 1946, he was arrested and sentenced to three years in prison, which he served in the notorious camps of Beden and Orman-Pojan. In 1956, he was ordained a priest and served for 12 years in Dukagjin, centered in Shosh. In 1967, he was arrested again and spent 23 years in various prisons and camps. With the dawn of democracy, he resumed his priesthood at the Church of St. Anthony in Tirana (December 25, 1990).

Since then, his passion for knowledge and culture has never ceased. From 1993 to 1997, he revived the magazine “Hylli i Dritës.” These years were also a time of great creative activity for Father Zef. He wrote and published the trilogy “Live to Tell” (Rrno vetëm me tregue), the volumes “The Great Franciscans,” “The Friar of the Bushatli Pashas, Erazmo Balneo,” and “Ut heri dicebamus – As we were saying yesterday.” Meanwhile, despite his advanced age and failing eyesight, assisted by his students, he continued working on other books.

One of his invaluable initiatives was the republication of the complete collection of Franciscan works, which had been barbarically removed from circulation and library shelves. This inspired body of work by distinguished Catholic clergy in the 1920s and 30s aimed to create a civilized Albania. It proves that what is truly valuable is never lost; it remains, and we must bow to them with respect.

In these years, Father Zef Pllumi also contributed to the education of the youth. Thanks to his intervention and persistence, nearly 150 young people were sent for university studies abroad. His influence also made possible the upcoming opening of the Austrian high school in Shkodër.

To understand the humane spirit of Father Zef Pllumi, I will share a personal encounter. After a warm conversation lasting two or three hours – where we spoke extensively on topics ranging from politics to science, from the past to the present – we exchanged books and shook hands.

For a moment, he paused and asked: “Did you have anything to do with Gabriel Meksi?”

“Yes,” I replied, “I am his son.”

He shook my hand once more and recounted an episode from his high school graduation exam in history. When young Zef began to answer, one of the teachers interrupted him, criticizing his expressed opinion. My father, present as a representative of the Ministry of Education that year in Shkodër, intervened to defend him, saying: “These answers are for me; let the boy continue.” The student of that time, Zef Pllumi, received the highest marks, and today, sixty-plus years later, he still remembered the support he received from someone he didn’t know and never met again. This is a rare, selfless gratitude among Albanians today – but not for a man with a heart as large as Padër Zef Pllumi.

The life and work of Father Zef Pllumi to this day, for the benefit of the people and the nation, clearly demonstrate his multifaceted personality: a man who overcame difficult trials with dignity, a prominent figure of Albanian Catholicism, and a distinguished man of Albanian culture. His name and his work are an honor to the Albanian nation, and it is our duty – and the duty of those in power – to grant him this recognition./Memorie.al