By Jerina LUKA (Rasha)

Second part

Memorie.al / After the fall of Communism and with the changes that the political system underwent in Albania during the 90s, the country faced many challenges. One of these was the commitment to show what had happened during almost 5 decades of suffering. Seeking to inherit the memory of the facts, as they really happened, is a paradoxical effort, that in the case of totalitarian systems, history has proven, that the issue becomes even more problematic. Many of those who experienced the terror of this savage regime first hand did not survive. While others who have survived, do not manage to pass on what they have really taken away and are almost incapable of articulating to the end, the lived experiences.

Continues from the previous issue

According to this article, for Shllak, there is an abuse of the meaning of the word “national”, since Albania, as a free country for 25 years, could no longer place the emphasis of development on “this term”, simply for the purposes of interpretation political, but it must take one more step, towards real development, respecting the diversity of opinions in the middle of society and not a unification of it.

Albania, for the author, must develop and flourish in the midst of heterogeneous opinions, certainly to the point where the common interest of society is not compromised, because only in this way, development is true.

According to him, a homogenous society paralyzes thought, knowledge, evolution, and that man, in addition to sentiments, also has reason, which must follow knowledge and truth, wherever he finds it, without being influenced by propaganda, which he considers as a tool. to realize the homogeneity of society’s thought.

He is against demagoguery and in favor of studies, especially those in the field of philosophy and sociology, as preventive tools against the inflammation or death of the society’s mind.

To the article “Are we getting along”?!(1938), a great concern for Shllak, is the lack of depth or the superficial ideas of anyone and anywhere, that they originate from. He mainly refers to the phenomenon that had begun to appear through some people, who at that time called themselves progressives, enlighteners or nationalists and who, according to him, only had bombastic statements and reasoning, behind which a refined maneuver of opportunism was hidden, to realize the interests their own.

For Shllak, this phenomenon was the most harmful thing for the Albanian society because, this way brought the belief in what the society really cares about, it forms a kind of apathy and thus begins an anarchy of ideas, from which sooner or later, can be generated great catastrophes in the life and well-being of the Nation.

Such a mentality, according to the author, allows nothing to be taken seriously and extinguishes in the individual any feeling of concern for disordered events, to the point that these abnormal or not good events become necessary and where the individual to be fulfilled, to rejoice and enjoy in chaos.

Father Gjoni admits that it is not an easy job to have ideas, and certainly not to realize them, but he is of the opinion that at least our duty is to instill in the psyche of the Albanian society, the invigorating norms inspired by universal love and justice, as a basis for building the idea of the State and the Nation.

He himself reinforces his idea, quoting Louis Pasteur who said that;”The greatness of human works is measured by the inspiration that caused them to be born.”According to Father Gjon, the Albanian society should seek its ideas from the true values and if these ideas are followed through with concrete actions, only then, great works can be realized and the development is indisputable.

“We have learned to blame our Asian Turks for the backward state of our moral, political and economic life. We have reasons, but to some extent” begins the article entitled “We don’t know why we want, why we don’t want why we know”, by Father Gjon Shllaku. He continues, emphasizing the fact that; The Turk of Asia has long fled from our territories and we no longer have the right to use it as a pretext for the carelessness and indolence of Albanian society.

All the Balkan states suffered the same fate, but according to Shllak, they knew how to heal from the past, without succumbing to Asian fatalism. According to him, history is the teacher of life that should clearly guide what direction the Albanian society should take and what should be the plan for the nation’s recovery.

He quotes Vangjo Nirvana, who in one of his writings, in “Albanian Effort”, writes: “To save us from our spiritual barrenness, we must reconnect with our great dead, we have a day that we must overcome for a better tomorrow. In order to achieve this, let’s turn from yesterday and be inspired by its spirit, by its virtues.

The past is ours. Our work. Tree of our virtues. We made it happen. And to follow the advice of a great critic, Sainte-Beure: To think a lot and sincerely about the past, to understand it well – it means to truly dream of the earth”.

Father Gjon Shllaku thinks that the elaboration or confusion that reigns in the values and ideas of the Albanian society is the main cause of disagreements, in social views. Modern morality no longer finds any reason to grasp and develop, so in the absence of dynamism of animating ideas, it perceives the rise of force systems.

Another concern of Shllak, which he reflects in his writing “New Breznia”, published in “Hylli i Drita” in 1938, is the life and future of young people in Albanian society. According to him, the youth does not have confidence in itself and is not predisposed to cooperate, for the same goals. Young people, in the eyes of Father John, are self-sufficient and are not encouraged or worried about improving their lives.

Other young people often show signs of megalomania and refined hypocrisy. It is enough for a thin slice of culture or, however small a work, to rise to the pedestal of the ignorant masses with a little advertising. In fact, for this reality, Shllaku does not place the burden of guilt on the young generation, but analyzes the entire context, where the phenomenon occurred and developed.

According to him, after the declaration of independence, the country was found unprepared, thus began the dilettantism of various efforts in the field of press and writing, fed in most cases, by lifeless copies of foreign ideologies that were often used for purposes of offensive sectarianism. Such a context, where educational programs and methods changed every three or four years, did not create a common effort or unification of opinions.

Even those who tried failed! According to Pader Gjoni, they failed because no one had the right experience to present two fundamental issues such as culture and patriotism to the Albanian society, on which the various efforts of the Albanian intelligentsia would be based.

Shllaku mainly emphasizes culture, since according to him, collective efforts to agree on what Albanian culture is, would bring about a state of unity and flatten excessive individualisms, which cause the destruction of themselves and each other.

He expresses the conviction that culture softens peoples because it makes them get to know each other and reconciles the disagreements that often arise from the limitation of a fanatical mentality. “A citizenship, which is the page of the culture of the feelings of a people, necessarily leads to the complete union in the truth, in the good and in the beautiful” he writes in this article.

According to Shllak, the individual is first a man of culture and then a patriot, since the duty of patriotism is a natural flow that comes to everyone, after a complete cultural development. For Father Gjon, patriotism is not only an explosion of sentiments, but the continuation of the fulfillment of rights and duties in the social circle that an individual finds himself in.

He closes his writing dedicated to the young generation, suggesting several tasks: to get to know each other more because, in this way, they will encounter common inspirations and feelings; to have respect for each other’s opinions and ideologies; to be honest and have clear ideas, to reject preconceived notions, prejudices and biases, and always to be open-minded.

Jjon Shllaku could not have made his reflections on the press of the time, another field that he knew very well, being active himself. In his writing, “Echo of the Press”, published in 1944, he criticizes the press because, according to him, it does not really reflect the spiritual currents of the country and considers it constantly dependent on governments.

He also worries about the lack of a common language of the press during that time or a tendency to make a selection of dialects in an arbitrary form and without scientific basis.

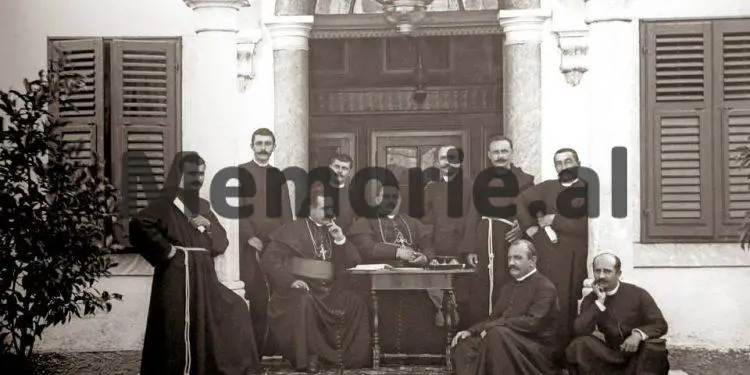

Very difficult times would come for Pader Gjon Shllak, the intellectual, academic, cleric, philosopher and patriot, before he was tragically killed, after a trial and absurd accusations. His life, young age, activities and contribution to the education of society, would stop once and for all, at the peak of age and intellectual maturity.

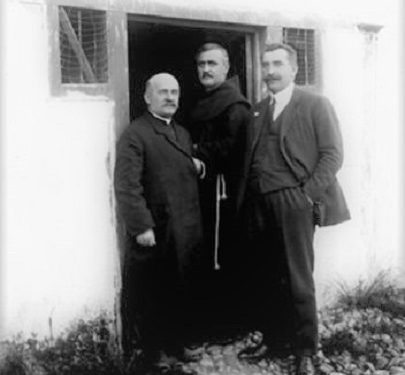

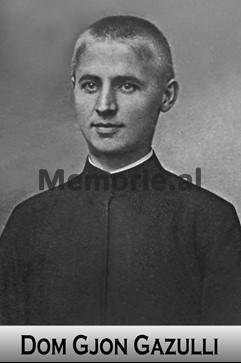

In one of his writings, entitled “Fate to be forgotten”, four years before he suffered the same fate, he dedicated a thought to Bajram Curri, Luigj Gurakuqi and Dom Gjon Gazulli: “On the other hand, the people of the ideal, we drowned for the living, they are honored for the dead. Sometimes they are drowned twice: they are also forgotten…! For Bajram Currin, Luigj Gurakuqin, Dom Gjon Gazullin, there was no need for a deka, with a florin cap.

Their lives are here, for what they did as martyrs for the freedom of the Nation. They begged for them to be removed, for them to disappear, because their lives were a gift for the treachery…! A nation that is born, needs fates that are desired. But the fates they want, they have nothing to do in a nation that forgets and despises them”!

This article brought to attention only some of Father Gjon Shllak’s articles, with the aim of understanding something more about what his thoughts and attitudes were on certain issues such as communism or the collective development of Albanian society. The selection of the writings was deliberate as the topics covered can still be considered essential issues for our society.

This makes Shllak, and above all his opinion, very current. From the analysis of the writings brought in this study, the conclusion is reached that; Shllaku had captured the essence of the problems that he deals with and that he knew the Albanian society very well. He was optimistic about the future, realistic and did not like passivity or victimization, which Albanians sometimes did because of unfortunate historical events.

He sought to see ahead and had at heart the orientation of society towards a real development. He was completely in disagreement with the “facades”, an individualist as far as knowledge and science are concerned.

He wanted very much that after a long period of invasions the Albanians would find a common language in defining what was the Albanian language, culture and tradition because this, according to him, would bring unity and level the individualisms that would harm Albania.

Unity should come from free and heterogeneous thoughts. Of course, a thinker who had these visions could not support or welcome communism, which, among other things, was the number one opponent of freedom of thought, expression and belief. Memorie.al