Memorie.al / In the short history of the Albanian short story over the last 50-60 years, Faik Ballanca undoubtedly holds a special place of honor, which I would consider in this case to be a tribute paid to him by the written work he left behind. And the resonance is felt. Even as strongly today as the day they were written and published, even though nearly four decades have passed. Summarized in four volumes, such as “The Abduction” (Rrëmbimi) – 1970, “Wet Afternoons” (Mbas dite të lagura) – 1971, “Anonymous Letter” (Letra anonime) – 1973, and “The Waiters of Lightning” (Pritësit e rrufeve) – 1975, a total of 45 stories are now the legacy left to us by this talented prose writer, penned in the span of a single decade.

In addition to these, he also wrote novellas and a novel based on the reality of those years. Ballanca also saw other publications like “Selected Stories” (Tregime të zgjedhura) – 1976, and “The God of the House” (Perëndia e shtëpisë). The latter is also a collection of selected stories, published in Prishtina in 1985.

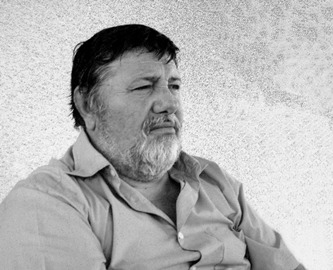

But who was the writer Faik Ballanca, who was at the time quite young compared to other creators who wrote the Albanian short story, such as Shuteriqi, Pasko, Gjata, Musaraj, Prifti, Andoni…?

Born into an intellectual family in the capital, originally from Dibra e Madhe, he studied journalism and immediately began working in the most important literary organs of that time, as a journalist and editor for “Zëri i Rinisë” and the magazine “Nëntori”. His close friends recall that Faik started publishing at the age of 17, and his talent clearly stood out during that period.

The writer and poet Rolan Gjoza says that Faik Ballanca was intolerant of the ‘chaff’ that newspapers and magazines published; aloof, gloomy, nervous, dissatisfied, he wouldn’t approach you, but he would give you a fragment of friendship if you got close to him. Let us not forget that, during this period, the Albanian short story had just begun to form its own physiognomy, under an unparalleled pressure with the political recipes of the dictatorship embodied in socialist realism.

But Ballanca never became a conveyor of this line and current that had gripped all our literature and art at that time. Because he felt completely different within his soul and world. Coldness and solitude gave him wings. He had a kind of guardedness towards others, his colleagues, and the literary environment that surrounded him. This may have saved the young short story writer from the ambitions and malicious attacks, which were always present, but which did not shake him to the extent of making him the next victim. Self-reliance thus became a life raft.

He had his own life and did not wish to impose on others. He was and remained a realist writer, within the boundaries of which he felt masterful. This is clearly distinguished not only in the structure of his story, which had no political load and did not include the campaign-style directives issued by the party, because he preferred the “natural and commonplace in literature,” but also in the creation and selection of his characters.

These characters are never found in Faik Ballanca’s stories as ‘leitmotifs’ reciting lines, but come from a rich and diverse gallery. They are simple and ordinary people who come from reality or well-known or unknown figures who come from the historical past.

To achieve precisely this, realism, he would go down and descend without any “party order,” as happened later during political campaigns with other writers, into a reality he sought to know and investigate, to then have it as the background for his own creation.

For more than three months, he was found in the highlands of Lekli, Tepelenë, in summer pastures among shepherds, and lived life amidst the troubles and concerns of these simple people, whom he also turned into characters in a novel and several stories of the time, with an astonishing simplicity, making them completely believable in his work. This was the voice of conscience and the worldview for writing a completely realist art.

Faik didn’t like the Line

In general, the characters in Faik Ballanca’s stories are people we encounter on the street, at work, with their troubles and problems. They naturally love, suffer; make mistakes, and die, because, above all, they are simply human. And the author does not prejudge them at all, nor does he heroize them, but he does not hymn them either. Thus, they are neither perfect, infallible, nor exemplary, as is often found in the overwhelming majority of the literature of that time, because we cannot find them in our real life either. Ballanca manages to discover the triumphant features of life, its value and meaning.

But let us return again to the wide range of themes and motives in this author’s stories, which are universal in his work, such as the theme of the village, the National Liberation War, border defense, the reconstruction of the country, the emancipation of women, the demolition of old prejudices, history, etc.

Undoubtedly, all these constitute the thematic range of Faik Ballanca’s creativity. But what is unique about his stories is the position he chose, the viewpoint, the manner of treating these themes, the way the story is constructed, the language and the style that this author uses. In all these aspects, he is and remains very far from the conformism and schemes of socialist realism.

Faik Ballanca masterfully sketches the reality and the entire Albanian environment of those years with a “brush,” using entirely economical details, which makes the prose writer of the ’70s unique and different from his contemporary writers in the field of the Albanian short story.

This is also evident in the characters he presents, and in nature, which in his stories does not simply have a decorative function, but serves the creation itself, as a sudden and powerful metaphor, which in its structure reminds one of the “Chekhovian” line of writing, even though the author preferred writers such as; Thomas Mann, Kafka, Camus, Dostoevsky, etc.

Ballanca is the short story writer who stands out for his artistic finesse, figurative language, and an uncluttered phrase. His narrative is and remains emotional. This has led to Faik’s stories being read again with pleasure, with the same emotion as when they were written and read about four decades ago.

I will recall here with a kind of nostalgia, the stories; “The Waiter of Lightning,” “Hold my coat for a moment, son,” or “The Abduction,” “Anonymous Letter”… which anyone might remember, for their interesting discovery and great artistic power, and the equally powerful messages they convey with the same love for the reader today, even though this author’s work concluded 33 years ago when he tragically passed away.

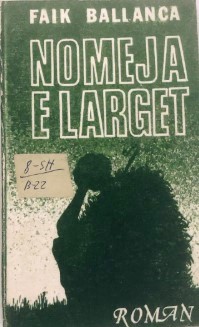

But it has found echo again with a different and completely new readership, mainly in reprints, such as the collection under the title; “Hold my coat for a moment, son” (Mbama pak pallton, çun), selected stories, published in 2003, as well as the historical novella, “The Last Song of Marko Boçari” (Kënga e fundit e Marko Boçarit) in 2002, which was very popular when it first saw the light of publication in Tirana, and was exceptionally well received by the critics of that time. Meanwhile, the novel, “The Distant Nomea” (Nomeja e largët), will soon be re-published, which was also highly praised as an achievement, not only for the young author of that period.

In the last 20 years, when all barriers fell in our country, and socialist realism is no longer the dominant ideology in art and literature, it is clear that; Faik Ballanca has been and remains an inspired realist writer, a forerunner who had long broken the “chains,” to be free in his freedom. He was and remains today a powerful and deeply realist writer, who honors Albanian literature. / Memorie.al