By Kozeta Zylo

Part One

Memorie.al / Professor Sami Repishti are an illustrious figure of the Albanian nation, an eyewitness to the communist hell. As a result, he was imprisoned for years in communist Albania (1946-56) and communist Yugoslavia (1959-60). This ordeal of suffering was endured by him and his long-suffering family. As an erudite intellectual, his writings have made a valuable contribution to journalism, literature, and politics. The messages he conveys from time to time regarding Albania and Kosovo are clear – from the American auditorium to the White House. He hopes that one day true democracy and full freedom will come to our long-suffering motherland and to the entire human family… one and inseparable!

Professor Repishti, you are one of the victims of communist terror. As a former prisoner of that regime, what can you tell our many readers about your years in the notorious prisons of Albania?

I was a conscious victim of the communist terror in Albania. I convincingly opposed the communist regime from its first days because, from the very beginning, the “State” initiated suppression and exercised terror. I witnessed arrests, imprisonments, public executions without trial, and the atmosphere of fear created by any terror, regardless of its color. I am an eyewitness. The second reason for my revolt and anti-government activity was the deeply oppositional atmosphere of the population of Shkodra, both in the city and the villages. This atmosphere grew even more acute in the first months of 1945, with the systematic persecution of the Albanian Catholic Clergy, centered in Shkodra.

The hope of the communist government that by persecuting the Catholic Clergy they would gain the “sympathy” of the Muslim portion was quickly extinguished; it was replaced by a spirit of Shkodran civic solidarity, which was later revealed during the continuous trials where the accused were both Muslims and Catholics. This atmosphere also oriented my activities. The third reason has a dose of youthful naivety. We hoped that the “great allies,” the Anglo-Americans, would intervene diplomatically to condemn the newly established regime and create conditions for a democratic development of the country and Albanian society.

This did not happen! Europe was exhausted by World War II and needed to rebuild the war-torn countries. Albania entered under the Yugoslav tutelage of “Comrade” Tito, who was a satellite of the Soviet Union and Stalin. Albania was thus a sub-satellite of the Socialist Camp. In this position of total submission, Albania lacked the necessary conditions to act freely. It blindly obeyed the instructions of Belgrade, which had its own “imperialist” plans for Albania: the political and economic colonization of the country, the Slavization of Albanian society, and a permanent solution to the Kosovo problem, possibly by incorporating Albania into Yugoslavia as a seventh Yugoslav republic.

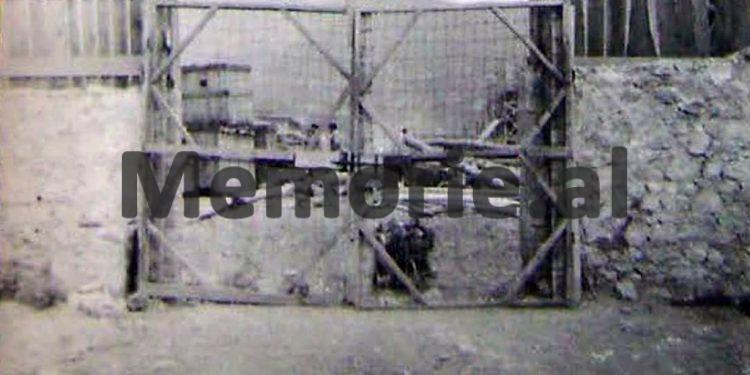

Such a terrible scenario naturally facilitated our “anti-power” propaganda work and found a great resonance among the population of Shkodra, a city with a centuries-old history of conflicts against Slavic attacks (Serbian and Montenegrin). But the political “moment” was against us. The peak of general discontent was reached on September 9, 1946, when the peasants of Postriba (in the districts of Shkodra) attacked the city with arms, fought in the city streets, but were defeated with great losses. Consequently, a wave of executions without trial and mass arrests began in the city and districts. The victims executed by firing squad numbered more than 100, while the number of those arrested, especially in the city, exceeded 1,200, confined in the 11 prisons of Shkodra.

I was included in this wave of terror, along with a group of active students. The tortures used against the “enemies of the people” cannot be described. Some detainees committed suicide, unable to endure the pain. Many others were crippled for life. The rest, including myself, spent 14 months in interrogation before going to trials – both public and secret – where sentences were handed down according to the instructions of party organs. This flagrant violation of the law was the “norm” established by the “dictatorship of the proletariat.” I was sentenced, on November 27, 1947, to 15 years of heavy imprisonment and forced labor. I served 10 years of this sentence in the Shkodra prison, and the extermination camps of Beden and Maliq, as well as the marshes of Myzeqe, and the airfields of Berat and Rinas (Tirana), from where I was released in 1956.

Our treatment by the prison guards was simply bestial. No law protected the prisoners, who were left at the mercy of criminal officers and indoctrinated “Red Guards,” embittered by the “daily propaganda education” provided by political commissars, and simultaneously victims of their own very low educational level (many were illiterate). They hated the “educated enemies of the people and the party” with all their souls. Until 1951, we had only one ration of bread for 24 hours. After 1951, they fed us bean soup without variation for long months. In the camps, they had potatoes, beans, and cabbage boiled in water and salt, and almost no oil. This food killed and sickened many prisoners, especially the elderly.

The terror of the camp is difficult to explain: it was daily, from morning until evening. Sometimes, even the night was spent outside, tied to trees or wooden poles. The work was heavy, the quota high, the conditions very difficult, and all under the fear of the guards’ whips, which they used without mercy. We worked in marsh water up to our waists, with leeches sucking our blood. A more brutal treatment than others was reserved for the “educated enemies of the people and the party” who had “poisoned the minds of the poor peasants.” On those evenings, long lines of the sick, the elderly, and those who did not have enough strength for work and did not meet the “quota” were not allowed to receive their bread ration or to go to bed until midnight.

The next day, exhausted by hunger and sleep deprivation, they would return to the canal at the insistence of those demanding the fulfillment of the “quota” just to secure their daily bread. There are enough books published in Albania that show in detail this regime of horror in prisons and camps, sometimes in unbelievable proportions, yet most of the time incapable of properly describing the monstrosity of the dictatorship. I remember a story from the Nazi camps. A prisoner begged a Nazi guard to kill him because he could not endure the torture. The guard laughed and said: “No! You must live and tell what you have seen, and I am sure the world will not believe your story. Then, it will be the true death for you.” Unbelievable!

What forced you at that crossroad where Albania stood to return to the fatherland, when you could have led a much more comfortable life in Italy?

I returned to Albania to help the resistance against the occupier. Like any young man (at the age of 18-19), especially an educated one, I was convinced that there in the mountains of Albania was my place. Staying in Italy became morally unbearable. At the same time, a lack of knowledge regarding the Albanian reality helped form such a conviction. Personally, I was torn between my belief that Albania needed cadres educated in Europe to assist its economic and social development, and on the other hand, the fact that Italy was an occupying state of my country, and it was the duty of everyone to fight it without compromise. My stay in Italy, in fact, was a form of compromise that I could no longer accept. Thus, I decided to return as soon as I passed my first-year exams in June 1943.

In the inhuman world of prison, you also encountered love – for the victims of that system – but with their rich spiritual world, you defeated the threat of death. How do you feel about this?

In the “inhuman world of prison,” where torture is hidden and where the threat of death reigns uninterrupted, everyone feels sentenced to death. A human feeling that loves life and despises death is dominant in such situations. This shared sense of imminent danger encourages mercy and love for one another, and for every individual who suffers: the victim. This feeling is known by the name solidarity: the solidarity of those sentenced to death, the tortured, the despised, the persecuted, of all those who are mistreated or feel “less than human,” inferior, second-class citizens, cast outside the boundaries of human society. The solidarity of prisoners is the medicine for survival.

Not only because in the company of fellow sufferers solidarity removes the misery of stifling loneliness, but solidarity offers the opportunity to help the other, the brother in suffering, and this act elevates the personal dignity of the prisoner; it gives, so to speak, a new dimension to the reason for surviving with an incomparable sense of pride.

The persecutors have still not publicly accepted guilt for the tortures they inflicted on the sentenced, the interned, and the exiled. Does this fluid state frighten you and why?

Yes, I am afraid. The failure to recognize and accept the crime/guilt by the perpetrator does not help the process of “catharsis” that occurs in such situations. An unfortunate development allows for forgetting, which in these cases, for me, is the second death of the victim. Where darkness reigns, crime is cultivated. New generations are growing up without knowing the truth about totalitarian systems, their thoughts, and their acts, and especially the irreparable destruction of the social fabric of the country. The communist dictatorship in Albania killed the elite, tolerated mediocrity, and elevated the dregs of society. The moral fiber of this society has been so severely damaged that today people think backward and work without any moral scruples. An entire generation has been lost, and I fear that a second one will be sacrificed in the mire that covered the country for half a century.

Did you think in prison that one day “the day of freedom” would come, and did you have plans for this great day in your mind, in secret with your fellow sufferers?

Yes! The hope for release from prison is permanent for every prisoner. It kept us alive. We expected the day of freedom to come with seismic shifts in our country. The communist building seemed strong on the surface, but it contained a series of unavoidable contradictions characteristic of any dictatorship. The oppressed person fights for freedom, and whenever given the chance, he or she erupts. In many cases, elements of the dictatorship have pangs of conscience, lose their initial “revolutionary” enthusiasm, repent, and seek to repair the damage caused, to help the victims. This is a universal characteristic. We saw this process even in Albania – even in prison.

“Plans for the future of our country” were the main subject of every conversation in prison. There were many divisions in the opinions of the educated prisoners, especially among those who carried the “baggage” of the past on their backs. But the idealistic youth without “baggage” were enthusiastic that the day would come when their minds and abilities would be put at the service of the fatherland. I have always dreamed of a free, independent, democratic, united, and Western (now European) Albania. My educational preparation and political upbringing before and during prison conditioned me for such a stance. Even today, I think as I did before. Youthful idealism? Perhaps! But I cannot give up that stance, because for me it would be my moral death. This perhaps also causes my pessimism today regarding the Albanian political class and the situation in Albania.

In those dark underground corners, was there any military man who, although holding the whip in his hand outwardly, had a spirit and eyes that spoke of something else?

Yes! There were “human beings” in the communist prisons. I remember Sergeant Jonuzi from Berat and a warrant officer from Vlora (I do not recall the name), who risked much to help us in difficult days. It is an indescribable feeling of relief that fills the heart of a prisoner when the “policeman” or “officer” does not carry out the superior’s orders for torture. There, it seems as if hope is nourished that there are still kind-hearted people in this world of evil, who, in difficult conditions, risk their lives to alleviate the suffering of others. Such elements revive faith in the goodness of human nature… even in the most anti-human conditions.

You were directly a manual laborer in the draining of the Maliq marsh. Under what conditions did you work there?

It is difficult to describe Maliq. Something has been written about this “black spot” of our history. Maliq was an extermination labor camp, where Albanian was killed by Albanian, by order from “Comrade Tito” in Belgrade – and killed with wood, with iron, by drowning in the marsh water, by hunger, by lack of sleep, with work beyond human strength, by being stripped naked on cold nights, or being tied to a pole, etc. In addition, the camp command incited ordinary prisoners – a true army of degenerate elements – as well as repentant former communists, to spy, provoke, and beat political prisoners. This forced us to defend ourselves collectively and to intimidate the attackers with revenge. / Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue