By Shkëlqim Abazi

Part sixty-five

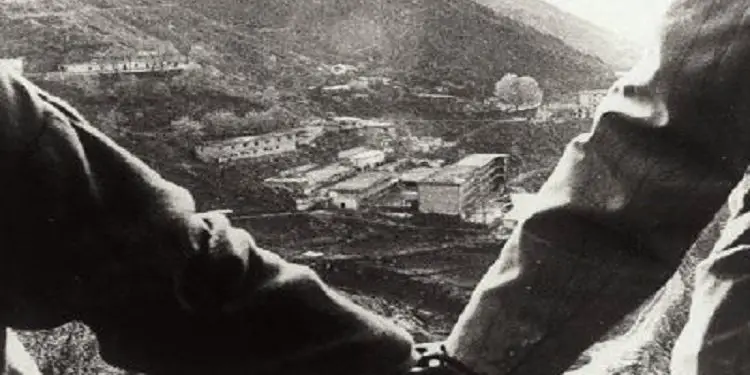

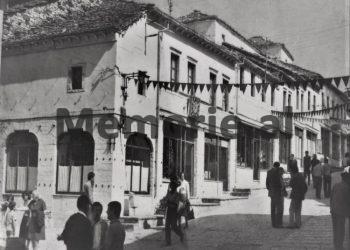

S P A Ç I

The Graveyard of the Living

Tirana, 2018

(My memories and those of others)

Memorie.al / Now in old age, I feel obliged to confess my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men who never boasted of their deeds, and of others whose mouths the regime shut and buried in unmarked graves. In no case do I presume to usurp the monopoly on truth or to claim laurels for an event where I was only accidentally present, even though I desperately tried to help my friends, who tactfully and kindly avoided me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you only have two months and a little left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the following months until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard those three days, I would not want to take to the grave.

“God only knows, mother!” – the reprisals of the Sigurimi (Secret Police) and the wave of arrests guaranteed no one protection from re-sentencing, let alone the hope of release.

“Mother, the Party knows best when to put people in and when to let them out!” the policeman interrupted, then barked at me: “You! Get inside, fast!” He shoved me aside to make way for the stretcher they were loading into the vehicle. I walked as far as the landing with my head turned back; there I stopped, watching my parents, who stood frozen a few meters from the gate. I pressed my fingertips together to blow them a kiss, but two drops of blood fell onto my lips. I licked them and felt the pulse of life.

A mother nourishes us for nine months with her blood, brings us into the world amidst a river of blood, feeds us with the essence of her blood – her milk – and then, and thereafter, gives her blood for the happiness of her offspring!

As I was philosophizing this way, my friends surrounded me and began asking for news from the free world. But seeing me empty-handed, they wanted to know what had happened. While I was recounting the details, a few drops of blood fell onto the cigarette I was holding and extinguished it.

“And this blood?” Tomor Balliu inquired.

“I tore myself at the gate’s cage.”

“You’re mangled, man! You need medical attention immediately!” Ahmet Islami shouted to a nurse passing by: “Hey Vani, can you fix this up a bit?”

“Bring him to the infirmary!” he replied and continued on his way.

With two or three friends, I headed to the Kosovrast clinic, which was unusually chaotic.

“What good wind brings you here?” the doctor raised his head from a ledger where he was noting something, but when he saw the blood flowing in a stream, he sat open-mouthed. “Where did you get cut so deeply, boy?”

“At the perimeter wire,” I replied.

“What were you looking for there? Did you get tired of life and want a piece of lead?” He lowered his head again and added something to the register: “Keep your eyes open, son, you don’t have much time left!”

“He was at a meeting with his parents,” Tomori explained.

“Ah, I thought he’d lost his mind!” The doctor turned to Vani: “Look at him while I finish the papers for this poor soul we sent to the hospital.”

“What happened to Jorgo that he needed urgent transport?” Ahmet asked.

“His appendix burst. There’s a risk of infection; God willing he survives, he’s still young!” The doctor continued writing. Vani twisted my forearm, scraping it with tweezers, which burned so much that tears welled in my eyes.

“The gashes are deep, doctor!” Something cold chilled my heart.

The doctor threaded a string as thick as a gut into a needle curved like a shoemaker’s awl. He plunged it into one side, pulled it through the other, and tightened the twine until he tied the final knot.

“Give him a tetanus shot; those rusty wires risk infection,” he ordered, his mouth opening in a yawn. Vani lifted my shirt and plunged the needle into the skin of my abdomen. Oh God, how it hurt – more than the arm!

“Lie down here or on the bed; your turn comes in half an hour,” he said, moving to the next patient.

“Why, is there more?!”

“Two more shots. But don’t worry; maybe the doctor will give you a couple of days of medical leave.” After half an hour, I left one room, went to another, and then another. The next day, no one gave a damn about the medical report; the police sent me to work with a stitched-up hand.

“To work, you! By the ideal of the Party, you’ll see what happens if you don’t meet the quota!” Pjetër Koka gnashed his teeth.

“I have a medical report!” I replied, handing him the paper.

“I’ll show you a report!” He snatched it and tore it into tiny pieces.

“Come on, leave the talk!” Caci took me by the arm.

During those days, my comrades were forced to complete my quota as well until my wound closed. But unusual situations temper character, just as water tempers metal.

Ymer’s Story

I hardly knew Ymer, whom those from Dibra called “Imer” while others called him “The Swede.” But during the days when he was forced to be both miner and wagon-pusher because I was injured, he revealed the noble traits of a highlander and a spirit of sacrifice.

“It’s alright, man, we’ll work for you until you heal! Would you do my job if I were sick? Without a doubt, you would!” With this rhetorical question, he justified his toil. Ymer was completely gray-haired, as if he were over fifty, when in fact he was only thirty. His somber features and sparse words were taken by us as a sign of regret for his unmotivated return from Sweden.

In the late fifties, he had escaped the country at a very young age. With the support of some Kosovars, he managed to immigrate to Sweden, where he settled beautifully. In his new environment, he was welcomed and guided toward trades. A youth with natural intelligence, he acquired a wealth of specialties in record time and became so well-known that he was sought after everywhere – and he repaid them with high quality and efficiency.

Over ten years passed this way, during which his wealth grew, but his youth was fading. Now thirty, he considered himself old to keep waiting; he needed to start a family. Not that there was a lack of girls in Sweden, but the traditional Ymer wanted a “woman for the home” and a mother to raise his children. He looked here and there, but found no one.

A colleague newly returned from Paris asked him one day to act as a translator at a fair. “I fell for a dark-haired beauty who, unfortunately, doesn’t know Swedish, but when I read ‘Albania’ on her tag, I thought of you! Please help me communicate with this Mediterranean beauty!”

This was roughly the request of the colleague who had done so much for him. Ymer didn’t think twice; he promised instantly, and the next morning they set off for France. At the European fair, they met a group of Albanians who – God knows how – had managed to open that pavilion amidst Parisian abundance. Regardless, he didn’t care for the answer to that question because, homesick for his country and his compatriots, he became so engrossed in them that he forgot the mission for which he had left work.

He even abandoned his “duty” once the girl cut him off: “No! I am not here to find love or start a family – I have those in my country – but to represent Socialist Albania!” Naturally, after the negative response, his colleague returned to Sweden, while Ymer begged him to stay a few more days with his fellow countrymen. To be honest, their talk grew sweet.

He asked questions, and they answered in superlatives about the cultural progress and the “righteous policy” followed by the Party for the strengthening of the socialist economy. Among other things, they gave him a mountain of illustrated magazines showing smiling, happy people enjoying socialist blessings like nowhere else in the world.

In his final days there, Ymer inquired about how they treated those who wished to return to the fatherland of their own accord. Were they welcomed or punished? Of course, the naive Ymer believed the patriots who stuffed him with lies – that no one would arrest or sentence him for the “crime” of escaping. “The Party is large-hearted with those who haven’t stained their hands with blood; it won’t even touch the wealth earned by your sweat; one can choose to live wherever they desire within Albanian territory,” and other endless nonsense.

Poor Ymer was so thrilled that he forgot the state of things ten years prior when he had fled. He swallowed the fairy tales about the prosperity of the land where he was born and raised. Like those from the remote fringes where news rarely arrives unreformed, he hoped for the welcome the authorities would reserve for him and made up his mind to return to the “Beloved Fatherland where his umbilical cord was buried.”

At the embassy in Paris, they received him quite well. They provided him with documents and invited him to return as soon as possible, along with his belongings and the money earned in emigration. This kindness dispelled the dilemma rising in the fugitive’s subconscious.

He rushed back to the Swedish town, his mind a whirlwind. He lost sleep, even neglected his work, and asked for a release – which, to be fair, they didn’t want to give him, but they were forced to by his persistence. They provided him with a positive recommendation and a hefty sum of money as a reward for his unsparing service to the company, seeing him off with special respect.

In his haste, he filled a truck with belongings, secured his money in a sister branch of the Bank of Albania, and hurried to Bari. In those days, ferry lines didn’t function like today. Waiting for trucks to Durrës, he stayed in a hotel frequented by Albanians who had fled long ago or recently. He met some of them and told them why he was there. His acquaintances unanimously disapproved; some were revolted and took him for an agent of Albanian Counter-Intelligence, while others boycotted him. When they advised him to withdraw from this dangerous venture and he didn’t listen, they abandoned him to the fate he chose.

Thus, amidst endless tribulations, he arrived in Durrës, but his belongings remained in Bari. For the moment, they settled him in Hotel “Vollga” (until the cargo boarding procedure was completed), but even after two days, the procedure hadn’t started. Relatives advised him to come to Tirana, where he could inquire with some high official – even Nexhmije Hoxha, with whom they claimed a distant blood relation.

So, with only the clothes on his back, two suitcases, and some pocket money – which constituted a hundredth of his emigrant fortune – Ymer reached the capital, where the bureaucracy drove him to his wit’s end. When he raised his voice, well-wishers advised him to calm down and be patient, as the “misunderstandings” would soon be resolved.

But even after a week, the “misunderstandings” were not cleared; even the interventions of high-placed friends were unsuccessful. No one showed up, except for the State Bank, which gave him a sum of money that provided some comfort. Under these conditions, he took the road back to Durrës to get information at the source, but they gave him no answer, only keeping him “in warm water”:

“The luggage may arrive from hour to hour; if not today or tomorrow, in two or three days,” that was all they said. The answer, neither fish nor fowl, distressed poor Ymer, who didn’t know where to turn. The predicted reality despaired him, and he began to churn over everything the recent fugitives had told him in the Bari hotel. When he remembered his friends in Paris, he pulled himself together slightly and returned to Tirana relieved. He stormed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but they sent him to the Department of Foreign Trade, where he again hit a wall of silence.

Drowning in deep despair, he nearly fell into depression. The loss of his fortune, especially the killing of hope for the future, shook his faith even in his own relatives. Right in these waters, two men in white trench coats appeared at his hotel, introducing themselves as representatives of the Ministry of Maritime Transport. They gave him a receipt accurately describing the cargo that had arrived at the port. Overjoyed, he signed quickly and set off immediately after the messengers.

But they stopped him at the port entrance on the pretext that it was a restricted zone. After he protested, they sent him to the Internal Affairs Branch – supposedly to get an entry pass. Behind the door, the two white trench coats who had taken his signature were waiting; now they handcuffed him “in the name of the people,” and he ended up from Sweden into solitary cells. After a few months, they held his trial, where he was accused of espionage and sentenced to fifteen years as an “enemy of the people” and “traitor to the Fatherland.” From then on, a veil of mourning settled over his dark face, which didn’t match the epithet “The Swede” at all.

“The head does it, the body suffers; it serves me right! I was doing quite well in Sweden; I wanted an Albanian bride, and they married me—right here in Spaç,” poor Ymer would reproach himself. Until the end of June, there were no developments worth mentioning, except for the beatings by the punishment group and the psychological torture caused by mandatory reading. On June 29 or 30, 1973, the farce of the trials for those arrested as the instigators of the revolt began.

Besides the first twelve who were sentenced by the Special Court on May 23 – four to death and eight to 25 years – over eighty others waited in the cells of Koçi Xoxe. Naturally, had they wished, they could have processed them all in a single session; after all, the sentences were predetermined and the witnesses were ready. However, they needed to divide them into groups for security reasons and to create a public sensation. Thus, they began with a group of twenty, including the designers of the Flag and those who had damaged the “emulation” displays. They were handed drastic sentences ranging from 13 to 25 years; only two managed to escape re-conviction.

As soon as the trial ended, they were returned to Spaç, mangled by torture and exhausted by hardship. By the very next day, they were assigned to the same fronts they had been pulled from three weeks earlier – only now, they were “promoted” to the role of miners, despite the fact that most could barely stand on their feet.

The following week, they continued with the second group; the same procedure followed, with sentences from 13 to 25 years. Then came the next group, and the next, until they finally completed the tally: approximately 1,700 years of prison – nearly two millennia. It is worth noting that the same witnesses appeared in all these court sessions.

As I mentioned, the witnesses were a few wretched policemen and a corps of prison informants. On this occasion, the State Security applied the Chinese axiom: “Rat eats rat,” which consists of biological warfare within the same species. According to ancient Chinese sailors who transported grain by ship, their cargo would be attacked by colonies of rats. To combat this, they raised rats in cages, starving them until they went mad, and then fed them rat meat. This repeated diet made the “warrior rats” so fond of the taste that they refused to eat anything else. Once embarked on the ships, they would hunt down their own kind in the holes where they hid and devour them, bones and all. They exterminated them all, becoming involuntary guardians.

Based on this method, the State Security incited a few salaried policemen and wretched scoundrels – Medi Noku, Agostin Peçi, Muhamet Kosovrasti, Thanas Theodhoraqi, Ilia Dhima, Zenel Balliu, Pandeli Pjetri, Miltjadh Papa, Hilmi Freskina, and others I cannot recall – who shamelessly testified against their fellow sufferers, earning collective hatred and contempt.

According to the accounts of friends who underwent the special investigation and subsequent trial, they were accused – with few exceptions – of active resistance against authorities, structured criminal groups, and terrorism. Naturally, these articles carried sentences ranging from ten years to death. However, for unknown reasons, the successive trials did not apply capital punishment; instead, they gave sentences of 13 to 25 years to over eighty people. Consequently, this was a slow death sentence, as no one was released without serving 20 years or more, and the last were only freed in 1990, thanks to political pluralism.

Can such madness be found anywhere else? It is like sentencing 51 generations, assuming three generations per century! In this regard, Enver Hoxha’s regime surpassed Genghis Khan; such tragic carnage is not encountered even in Ancient Egypt, Ancient Greece, or Ancient Rome.

With these draconian measures, the communists aimed to terrorize the people and eternalize their power, but the result was quite the opposite. Besides their real enemies, they earned the hatred of the “silent majority.” Thereafter, they began a power struggle and devoured one another’s heads in internal feuds. The post-revolt statistics show a shocking total; the groups would follow in chronological order, and the heads of the members of the Politburo would fall so frequently that after the dictator’s death, his old comrades could be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Thus, the Spaç Revolt shook the foundations of power like a tectonic shift, accelerating the decay and subsequent fall of the tyrannical regime. In this way, the prophecy of the doctor-writer was being fulfilled: “This event had to happen, to show the world that liberty does not die, even if it has languished for thirty years under the most brutal violence mankind has known. National history will be enriched by a unique fact that will have lasting effects, shaking the foundations of the regime and bringing its end closer!”

The echo of this tirade would last for two decades until it embedded itself in the minds and hearts of every Albanian, leading to the repercussions of the early nineties! The stars that shone during the long communist night are fading away. On the evening of March 9, 2018, I received the bitter news of the passing of my prison friend, Neim Pashai./Memorie.al