From Lumnie Thaçi-Halili

Part Two

Literary Research on the Book “Memories of the Time with Kadare,” by Sulejman Mato; URA, Prishtina, 2025

Authenticity as the Axis of Literary Narrative

Memorie.al / The literature of memoirs are one of the most delicate spaces where memory and art intertwine. It gains a special dimension when the author chooses to write not about himself, nor about the work of a colleague, but about the person hidden behind the writer’s public figure. In this territory, sincerity becomes a literary act as important as language or style: to portray a friend with all his light and shadow is to affirm that truth, no matter how complicated, serves memory better than the weaving of glory.

Continued from the previous issue

The author of these memoirs emphasizes the mention of a fact in “The Palace of Dreams,” which emerges as a cornerstone in Kadare’s creativity and unites the triangle with “The General of the Dead Army” and “Chronicle in Stone.” In relation to Kafka and Ionesco, the novel demonstrates Kadare’s power to expose totalitarianism; Ebu Qerimi, the bureaucrat of dreams, embodies the invisible mechanisms of fear.

Its publication in the climate of Article 55 and Dritëro Agolli’s caution in the Writers’ League shows that the work required not only talent but also intuition to face censorship (p. 203). In the work “Memories of the Time with Kadare,” the mention of the ‘Nobel Prize,’ as Sulejman Mato describes it in the narrative unit “The Nobel Prize” (p. 239), deserves special attention, as it reflects on Kadare’s unique position and the relationship between art, politics, and cultural affiliation.

He shows that a writer’s value is not measured by receiving this Prize, but by the endurance of the work in critical consciousness. Kadare, even without the ‘Nobel,’ has won international appreciation and admiration, remaining independent of the political scandals that often accompany the award. The memories from Moscow and Paris reveal his identity as an author between the East and the West, while Paris becomes the space for creative freedom.

Religious and cultural affiliation does not appear as a limitation, but as artistic material, and every personal or historical memory transforms into universal wealth. Essentially, Kadare’s greatness lies in the ability to turn his people’s history into literature that speaks to the world. Thus, this balance between respect and stripping bare makes his work more credible and more valuable, because it gives the reader not only the public figure of Kadare but also the person hidden behind him.

Kadare’s Complex Portrait: Between Myth and Man

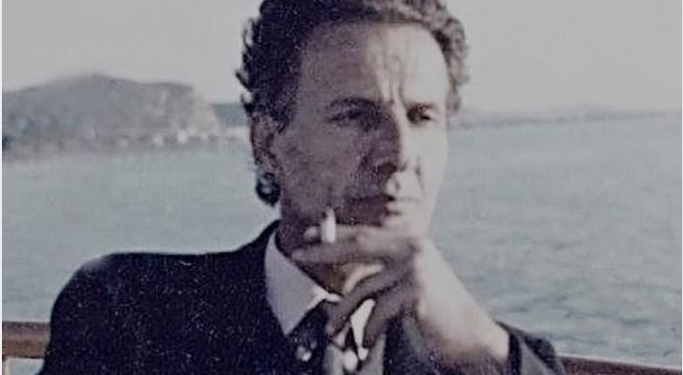

Throughout the book, Kadare’s figure is constructed as a mosaic of memories, events, and reflections, not as a linear and uniform portrait. Sulejman Mato presents his writer friend with a realism mixed with respect, avoiding both extremes: unconditional idealization and purely critical exposure.

The portrait that emerges from the pages of this book is vibrant, dynamic, and filled with human shadings. The author sees Kadare simultaneously as an extraordinary literary figure and as a man with ordinary habits, with his quirks and customs.

He recalls the subtle humor, the sudden outbursts, the nervousness towards colleagues, but also the calmness of a person weary of the abrupt fame he achieved in his youth. Daily rituals are mentioned: coffees, the cup of Turkish coffee grounds, walks in Gjirokastër, the careful giving of gift books, just as much as fragile intimate moments are described: the relationship with Helena, the love for his family, the care for friends, the longing for his birthplace, etc.

Mato also highlights his creative moments: the writing process, the way Kadare selected details from memory, his relationship with folklore, with Homer, Shakespeare, or Kafka…! He recounts how books were born from the “internal laboratory” of his imagination, how they adapted to political circumstances, how they were defended against censorship, how the gates of the world later opened, etc.

At the same time, the book illuminates social relationships: early friendships, admiration for some authors, as well as tensions with others (e.g., Neshat Tozaj, Nasho Jorgaqi, Bilal Xhaferi), the measured caution in apologizing to those he might have hurt through his art…!

Here, Kadare’s figure does not appear as a flawless hero, but as a complex personality, where the writer’s permanent modesty is interwoven with the legitimate pride in his work; humor with silence; benevolence with distance. The memoirs are not strictly ordered along a chronological line; instead, they build a polyphonic portrait, constructed from episodes, conversations, literary analyses, travel notes, and intimate scenes.

In the end, the reader considers not only the monument of Kadare, but also the man who stands behind it: the great creator, with a heart full of memories, with a talent that bursts over reality, but also with the hardships, fatigue, disappointments, joys, and sorrows of that life. This interweaving makes the book credible and emotional for the reader, giving a human dimension to the figure of the writer who is usually seen from afar, only through his work.

The question naturally arises: does this work bring a dimension that literary criticism fails to fully encompass? And, furthermore, what value does it add to the literary and cultural memory of the time when it is read and interpreted by the reader himself? As a result, the answers come naturally, that this book stands much higher than an ordinary memoir, because it unites three layers that rarely meet in one: personal narrative, critical observation, and philosophical reflection on literature and time.

In this spirit, we recall the expression of Rexhep Ferri: “Time can also be presented as a distant or close space, for human relationships” (R. Ferri, Gabime të bukura, ASHAK, Prishtinë, 2015, p. 139). This book does not present photographs of Kadare’s life, but wholly conveys a literary consciousness. The episodes are carefully selected from the writer’s experience, who knows how to extract only the meaningful moments, leaving the reader the opportunity to conceive the work as a photo album. Its main value is that it brings Kadare’s figure down from the pedestal of myths and places him in the soft light of the human.

Literary criticism has spoken at length about his literary works, but it cannot recount how he laughed in a cafe, how he hesitated to ask for practical help, how he remained silent so as not to hurt someone, how he protected himself from loneliness with humor or work…! Here, Mato highlights the friend’s “inner pulse,” as a mixture of simplicity, pride, shyness, and irony, which cannot be seen in academic analyses.

This book is a valuable addition to the literary and cultural memory of the time. It reconstructs an entire landscape of the Albanian world during the second half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, such as: the Writers’ League, the cafes of Tirana, the stone city of Gjirokastër, Berat of the thousand-and-one windows, Saranda of vacations, much later the quiet Qerret, conference auditoriums, official ceremonies, but also the intimate tables where ideas and literary projects were born.

Through many networked scenes, the reader sees not only Kadare but also the history of a generation of creators who faced censorship, maintained humor, and elevated literature above the calculations of fear. Even deeper, the book is a literature of commemoration. It transforms the past into poetic material, clothing memory with the shadow and truth of the word. The friend’s portrait becomes a human testimony freed from rhetoric, while the author builds an intimate space where the reader steps behind the scenes or the hidden corners of the myth and sees the real person as he is, with his hopes, doubts, and pride.

It follows that the memoirs are not merely an archive, but energy that revives time, a way to save from oblivion the people and books that have shaped our culture. In this sense, they transform into a conscious cultural testimony, offering future generations the experienced truths about how Albanian literature was written, defended, and ascended to its peaks.

As a restrained homage, built upon a narrative that is both intimate and public, the book appears as a treasure of national memory, where the writer friend and the author, also a writer, unite in a narrative that reveals the beauty and the tragedy of the creative path.

The next question naturally arises: is the bibliography about Kadare enriched through a human testimony? The answer is yes. Sulejman Mato’s work significantly enriches this bibliography, entering a space where critical studies usually fail to penetrate: the writer’s life and the atmosphere of his relationships with people and time. Scholars of Kadare’s work have mainly focused on his literary activity, offering valuable analyses, but usually remaining on the cold plane of theoretical argument.

Mato’s book warms the critical landscape, bringing the living voice of the creator, everyday gestures, spontaneous conversations, and emotional experience. It offers what theoretical criticism often overlooks: Kadare’s human portrait, with light and shadow, creative rituals, and social relationships. The work connects the writer with the cultural and historical context, the Writers’ League, the formative cities, the dictatorship scene, emigration, and the return home. Thus, personal memory transforms into a documentary source that enriches Kadarean studies with data unattainable through cold theoretical analysis. In this interweaving between document and experience lies its value: a vibrant testimony to Albanian literary life.

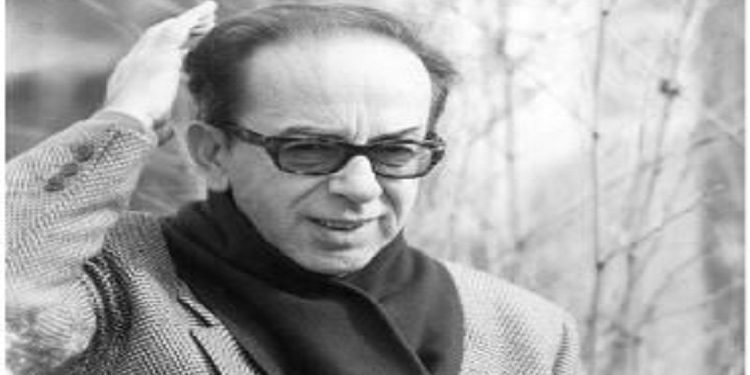

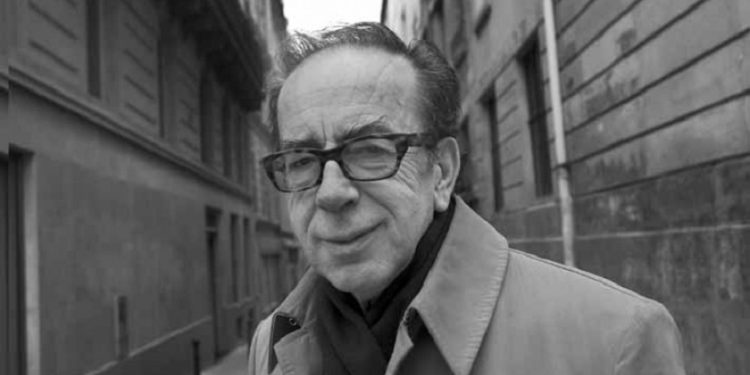

Sulejman Mato’s Indirect Self-Portrait in the Book

Throughout the book’s reading, it is clear that besides Kadare’s portrait, an indirect self-portrait of Sulejman Mato is also inevitable. In every chapter, while recounting the life and work of his friend Kadare, the author also highlights himself, the man who lived close to Kadare, the writer who shared with him the time he recounts, the passions and anxieties of creation, the citizen who endured a harsh regime without losing his love for literature.

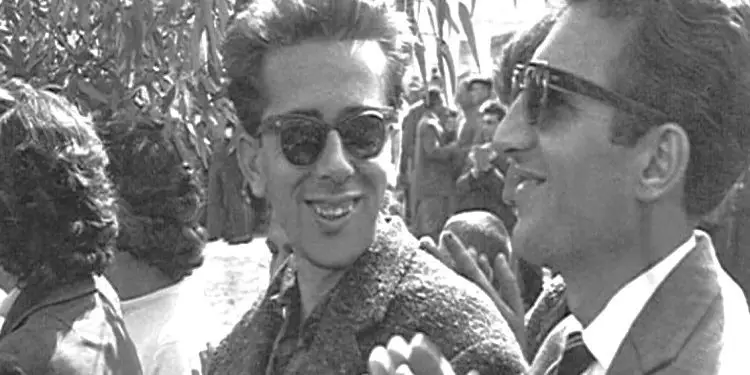

Simply put, their friendship was based on mutual respect. He shows that he knew Kadare since early youth, in Gjirokastër, Berat, and Tirana, where this relationship passed through many phases: conversations about literature, exchange of manuscripts and books, travels, friendly dinners, moments of humor, but also long silences.

However, a deep gratitude is maintained in every episode. Mato acknowledges Kadare’s talent, the influence he had on him, the greatness of his word, while Kadare respected Mato as a conversational partner with a vibrant memory and sharp literary taste.

Kadare himself later confirms this in a friendly conversation, stating: “In Berat, if I hadn’t had Sul Mato, I don’t know what I would have done.” (p. 251). This affirmation places Mato in a narrow circle of trust, as a man who helped him maintain a connection with the memories of youth and with a world that often seemed distant. In the memories of his youth years in Berat, the youth actions, and the nights of literary discussions, Mato presents a generation that grew up with a thirst for culture under the pressure of ideology.

His portrait reveals a calm and contemplative nature, but also a determination to defend free art in any circumstance, as well as his convictions and his religious philosophy, present in one episode of the book (p. 83). In conversations with Kadare, he is not just a listener, but a conversational partner who asks challenges, and shares doubts.

This equal relationship gives the memoirs a friendly, non-servile tone. To be clear, Kadare played the role of a silent mentor: he read Mato’s manuscripts, made notes and comments, and supported him with quiet but significant words. He was not one to praise someone excessively, but when something touched him, he stated it clearly. This appreciation was an implicit form of respect for Mato.

Sulejman Mato often recounts his creative world, his first stories, the manuscript books he gave to Kadare, the emotion of a brief evaluation from him. These narratives reveal him as a writer seeking authenticity, who sees literature as serious work, not as decoration.

All these testimonies, told with sincerity, show that Kadare is equally present as a citizen in the part of the book “Years of Coldness” (p. 223), where he appears hurt by censorship and institutional obstacles, but without malice, with the philosophy of a patient sage who accepts the trials of time.

But there are cases in the book when Kadare also appears distanced from Mato, not out of lack of respect, but because of his reserved character and work-focused nature. There are even periods when they do not meet, and even when they do, certain indifference appears, such as the case in the bookstore when he does not immediately greet him, or gives short answers about the deaths of mutual friends.

However, these are not hostile coldness, but signs of a personality focused on his own creativity, which sometimes loses the sensitivity of the moment. The chapter “The Year 1967” shows this best, closing the Berat period and opening the horizon of Tirana, giving Sulejman Mato’s memoirs a clear line of development. The narrative builds a natural triad: leaving Berat, the birth of a new poetry, and the author’s entry into the Writers’ League. These three moments give the book a rhythm and transform it into a pilgrimage initiative, where Kadare’s fellow traveler gains a new, serious literary identity.

Among other things, the book brings some prominent and clearly meaningful scenes, such as the visit to congratulate on Besiana’s birth. Although filled with expectations of courtesy, this scene presents, through a calm lens, the contrast between the world of the powerful and the simplicity of the narrator and Mato’s wife, Maria. The description of the small reception room, filled with well-known figures of the system, creates a cold background where conversations are limited to external details, lipstick, and perfumes as signs of privilege and distance from ordinary reality. In this context, the sensitivity of Maria, Mato’s wife, stands out, as she does not engage in the race for luxury but remains reserved and authentic. Thus, her figure emerges as a natural counterweight to the society of power.

Subsequently, the complicated relationship between Kadare and Enver Hoxha is also raised in the background through the book, reading them as two figures emerging from the same cultural soil but placed in antagonistic roles: the politician of absolute power and the writer seeking his own space of freedom for creativity. The narrative sets the scene as an internal drama of power, as the entry of Kadare into the “Bloc” is recounted, the tense waiting, Nexhmije’s calm smiles, the dictator’s measured words. All create a charged atmosphere where the subtext weighs more than the expressed dialogue. Therefore, the author uses this instance through a sustained contrast between flattery and suspicion. Enver, weary from illness, needs the writer to breathe life into his memoirs, but, at the same time, he sees him with a critical eye, careful not to lose control. The gift of Balzac’s works carries the weight of a secret invitation to collaboration, but also of a test of trust. Kadare, with the sharp intuition of a man of letters, understands the power game by maintaining the necessary distance.

In the final chapters, “The Last Meeting,” “January 2024,” (p. 244) a fragile and nostalgic Mato emerges, confronting the loss of his friend, which he experiences as the loss of a part of himself. The feeling of gratitude and respect does not prevent him from maintaining a measured, restrained tone, with a balance between pain and the calmness that time brings.

Through a careful selection of episodes, sometimes bright and sometimes hazy, Mato narrates, among other things, his philosophy of life and art. Literature is presented as testimony and spiritual adventure, while memory is not just an archive, but a way to understand oneself. Friendship, on the other hand, appears as a space of trust, but also as a challenge to maintain sincerity. In this sense, the book can sometimes be read as a book of two interconnected portraits: one of Kadare, the genius master of the word, and the other, of the author who follows him, analyzes him, and measures him against his own life. /Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue