By Sokol Gruda, London

-Testimony David Smiley, former military commander of the training camp of Albanian saboteurs in Malta-

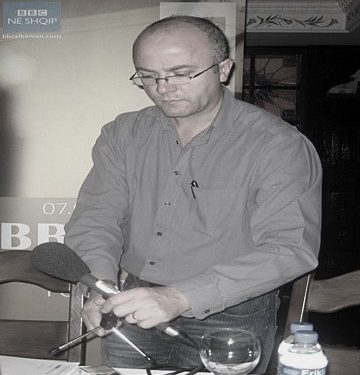

Memorie.al / During the Second World War, he worked with Enver Hoxha and Abaz Kupi, for the organization of anti-fascist forces. With the fall of the “Iron Curtain”, he trained saboteurs to overthrow the communist regime. The 90-year-old English colonel, David Smiley, explains after more than six decades, the wrong decisions of London that allowed Enver Hoxha to come to power. On the evening of November 28, 2003, two years ago, at a reception of the Anglo-Albanian Association in London, I was introduced in Albanian, with an elderly man who had taken a seat in that corner of the hall where the “masters of the house” sat. . From the sound of his last name, mixed with the clinking of glasses and scraps of conversation, I thought I had met the father of one of my compatriots at that reception. “I’m David Smiley,” he explained simply, shaking my hand. “Colonel David Smiley,” he continued, as if to dispel any misunderstanding.

We exchanged business cards and left to see each other another time. “Perhaps for an interview?” I boldly tried the chance. “Perhaps somewhere quieter,” he said, pointing to the hearing aid in his ear. When I met Colonel David Smiley again, the streets of London was filled with posters of the 60th anniversary of the victory over fascism in Albania, and perhaps preparations had begun for the 15th anniversary of the overthrow of the dictatorship. There was probably no better moment to meet Colonel Smiley, who for better or for worse, he left his mark on both of these events.

The two arms of Albania

On the second floor of the flat, in a quiet neighborhood in west London, Colonel Smiley himself opens the door for me. He leans lightly on a modest cane, but he squeezes my hand tightly and his eyes do not move as he welcomes me. We relax in the living room and the colonel treats me to Albanian brandy, brought by his Albanian friends. The conversation becomes more pleasant after this little surprise. We begin to talk about events that began a quarter of a century before I was born, in a place unknown to him: “Albania was occupied by our enemies, the Italians. It seemed quite primitive, wild, but very attractive place, especially in the mountainous areas where I spent most of my time. As a guerilla fighter, I couldn’t have found a better place to work. I was part of the SOE- (Special Operation Executive) organization, based in Cairo.

The SOE organized the dropping of British troops and citizens from those countries into the Balkans, with the aim of undermining German military operations and causing as much damage as possible to their troops. Together with my friend Billy McClain, we agreed to go to Albania, a country where no one from our organization had ever set foot. It was April 1943, when we entered Albania from Greece, after two days of walking,” Smiley remembers those turbulent days. Together with his colleague, McClain, they had preferred the longest route, to avoid as he says, “parachuting in the hands of the fascists”. He had heard that the Albanians were generous and hospitable.

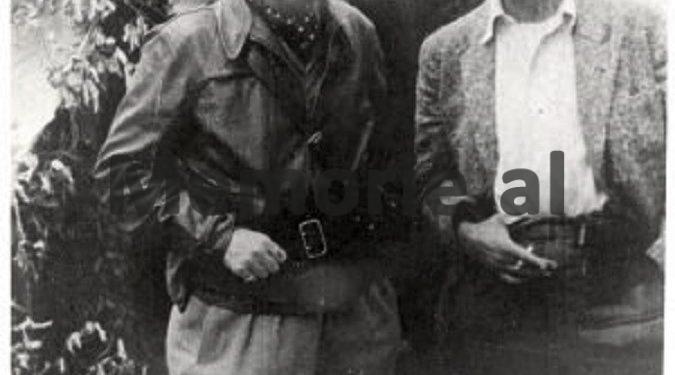

“The first Albanian we met was the commissar of a gang, who didn’t like us and asked us to leave. We had to leave Albania, but I returned again, via another route and entered the vicinity of Korça later, when they learned that supplies could come to us from the air, the partisans began to show a lot of interest in us, and even invited us in. For nine months, we worked together with the partisans led by Enver Hoxha.

After the meeting with the first partisan squad, it became very difficult for us to get in touch with anyone else, because the partisans did everything possible to prevent us from getting close to their political opponents, the Ballists, or the Zogists of Abaz Kup. Enver Hoxha led the Communist Party. I worked with him during most of 8-9 months, helping him arm various detachments, mainly in the South of the country, near Korca and the surrounding areas”.

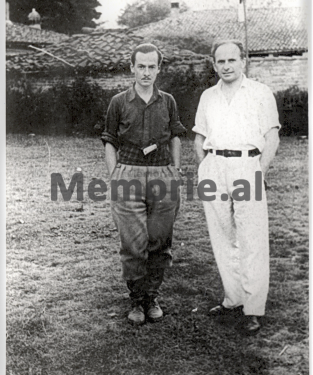

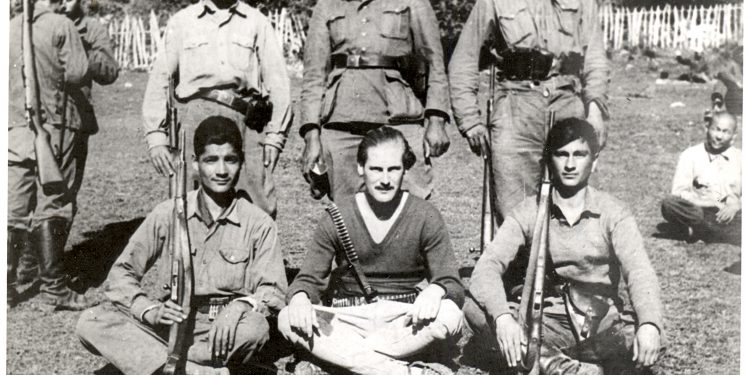

Colonel Smiley is approaching his 90s and is one of the few witnesses, perhaps the only foreigner, who lives to testify to the behavior of Enver Hoxha, when he had not yet taken power in Albania. His memories are refreshed by the photos he took with his own camera during the war in Albania and the many books. In the library full of publications about Albania and Kosovo, I see the title; “The Anglo-American danger for Albania”. He tells me he has read all “his” books.

“I developed antipathy for Enver Hoxha, almost from the first meeting. It was clear that he did not have any regard for us either, but he tolerated us, because he knew that we would help him to create partisan squads. Hoxha was hot-tempered and often I got busy with him. Although he was a yelling and angry guy, I worked with him from April 1943 until I left in October-November of the same year,” recalls the former British captain.

“On one occasion, he got very angry, because without his permission, I blew up a bridge. I told him that I had come to Albania to fight the Italians and Germans. Enver Hoxha insisted that I should have been authorized by him. I I explained that I was not under his command, that I was a British officer and I received orders from my Headquarters in Cairo, and later in Bari”.

Colonel Smiley says that he had bad experiences with other communist figures of the war in Albania. With the photo album in hand, he stops at the unmistakable portrait of a partisan, with a mustache. “Mehmet Shehu! My enemy to the death! Except he spoke very good English, so as not to eat his hack”.

However, the disagreement with the Albanian communists should not have been the only impetus for the temporary departure of the missionary Smiley and his colleague McClain. “After 8-9 months in Albania, I was evacuated and returned to England. Together with my colleague Bill McClain, I met the Foreign Minister, Antony Eden, who told us: “Go back to Albania and try to organize the families, mainly Catholics of North, in the war against the Germans”.

“Not much time passed and we were parachuted into a hilly place, near Tirana. For six months we stayed with the forces of Abaz Kup and with some detachments of the ‘Balli Kombëtar’. We fought several battles. As I remember at that time, the partisans did not fight, except when they were attacked. When we were still in the North of the country, the British sent a commando to South Albania.

The Germans were retreating from Greece and we wanted to cut their forces to pieces. But, by order of Enver Hoxha, the commissar of the area, he refused to cooperate with the British. Hoxha’s forces knew that McClain and I were anti-communists, so they did their best to get rid of us. There came a time when they even put a bounty on our heads. For some time, until we left the sea, we had to be protected from both the Germans and the partisans”.

But not everything was in the hands of Smiley’s own military experience and political flair. The British headquarters had decided to support Enver Hoxha’s forces and a soldier like Smiley, who had helped the anti-communists, could continue to stay in Albania. “We left indignant. Our headquarters had decided to transfer all aid to the communists and withdraw the British officers from Abaz Kup’s and Balli Kombëtar’s troops,” recalls Smiley. As the British mission multiplied aid to the Communists, David Smiley, the first Allied soldier to be dispatched from the SOE Operation Headquarters in Albania, left disappointed and indignant.

In the armchairs of his living room, Colonel Smiley admits that his staff’s decision may have been dictated by circumstances. “Ballistas and birders did not fight the Germans much, because they probably expected to see what direction the war would take”. But even 60 years after the end of the war, Smiley has not changed his mind about the right wing of the war in Albania. A white vulture is among the first things that catch your eye at the entrance to his apartment.

“There are many who do not agree with me, but there are many others who think like me. If during the war, we had supported the right, they would have fought, which they did not. They were well trained and they had officers from the gendarmerie. I think they would have really succeeded, if the British had not suddenly decided to pass all the aid to Enver Hoxha”.

But does Colonel Smiley agree with the opinion that most of the 30,000 Albanians killed during the war were on the side of the communists and not of their right-wing opponents? My question silences him, for a moment. He doesn’t answer right away, but I’m sure he heard me.

“I think that Enver Hoxha was completely heartless in the fight for the elimination of political opponents, even when he had not yet taken the reins of the country in his hands”, the former captain of the war begins to answer me and continues, categorically: ” The partisans killed a lot of ballistas and birders, and when we left, the country was in a civil war. I’m sorry to say, but the communists won, because they had better weapons, and they had more experience mountains. They were better equipped; thanks to the help they got from the British.”

Why did the efforts to remove the communist leader from power fail? Who betrayed and the role of Abaz Ermenji and Abaz Kup?!

Across the Iron Curtain

The entry of the partisans into Tirana could really look like a festive platoon in the great march of the victorious allies. But the red parade, which started from the shores of the Baltic, had arrived in the Adriatic. In 1946, Winston Churchill diagnoses the state of post-war Europe in this way: “An iron curtain has fallen across the continent”!

When they realized what was happening in Albania, Smiley’s bosses in London opened the old war maps again. Enver Hoxha should be removed, by his own people. The operation needed a political and military base. Experienced players were again brought to the field. It was precisely the fall of 1949, when the name of the former missionary, David Smiley, was again associated with Albania. He was appointed military commander of the saboteur training camp in Malta.

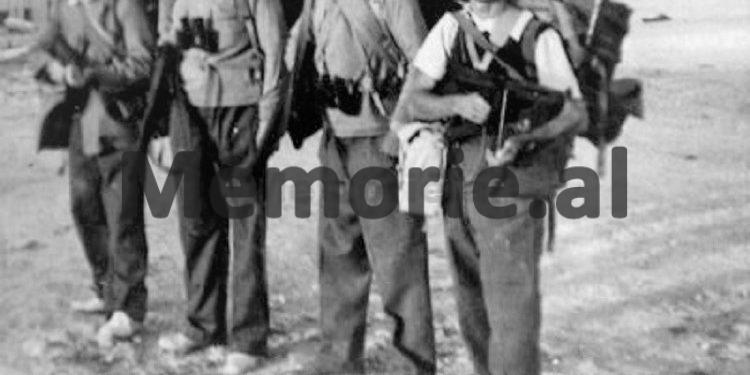

“It was a joint Anglo-American operation. At that time, the “Free Albania” Committee was formed, mainly with people from Abaz Ermenji and Abaz Kup. They had decided to send some Albanians left after the war to Albania, to see the possibilities of mining of Enver Hoxha’s regime. I was charged with the task of training these Albanians. After some time, they were thrown into Albania. Unfortunately, only a few escaped cases, they were ambushed. The reasons would be found out later.

Since we were cooperating with the Americans, we had to tell them what we were doing. The Americans themselves had started parachuting landings in the North of Albania, while I was operating in the South, sending my landings from the sea. It happened that the person who liaised between the British and the Americans in Washington was an agent named Kim Philby. He sent all the information to the Russians, who then passed it on to Enver Hoxha. Therefore, Hoxha knew our actions accurately. We were betrayed by a British traitor!”

Colonel Smiley does not forget to point out once again the qualities of the Albanians he trained for many years in the Malta camp. “All the people who jumped into Albania were patriots and very brave. I was extremely sorry when I learned about their fate. They were recruited by Abaz Ermenji and a part by Abaz Kupi. The recruitment was done on a voluntary basis, mainly by refugee camps in Germany, where many Albanians were concentrated. Then they came to me to train as guerrillas. I was deeply disappointed when I learned that they had managed to escape in Greece and told us how they had been ambushed. According to them, this had happened either because someone had betrayed them. I did not know what to tell them later, when first two agents (Guy Burghes and Donald Maclain) and later Philby, escaped to Moscow. We had been betrayed.”

The British were the first to admit that the operation had failed and efforts to cause unrest in Albania had to be stopped. Neither their own experience nor the models in the neighboring countries helped the organizers: “The same problems also existed in Greece and Yugoslavia. In both cases, they faced two fierce political opponents, the right-wing and the communists the two cases, there was a civil war. In Yugoslavia we supported Tito, against Mihajlovic, which I think was a wrong decision”, says Colonel Smiley.

“Fortunately, despite the advice of the Americans, we sent troops to Greece, which blocked the way for the communists to take power. This is the reason why Greece did not remain behind the iron curtain like Albania and Yugoslavia.” From a Greek island on the other side of the Iron Curtain, Colonel Smiley and operatives of the counterintelligence services recorded the damage of the betrayal that brought about the failure of the Albanian operation. Several dozen killed residents and saboteurs. Both Albanian parties! Was it worth it? And weren’t the subversive Albanians themselves left in the mud by their foreign masters?

“I can even say that they were left in the mud by me myself. After all, I was the one who, in good faith, sent them to Albania, not knowing that we were betrayed. They were very brave men and I can’t find the words to express my regret for their fate”, says Colonel Smiley.

“Groups of paratroopers, usually four people, were ambushed. They were captured, tortured and shot. Our operation aimed to see the reaction of the people to Hoxha’s regime. But it turned out that they were so scared that they could not help them the people who landed. The answer was that it was not worth sending the other forces, because Enver Hoxha had the country under complete control and the people were terribly afraid of him. I met some of the landing forces later in Greece and no one was angry with me. I want to clarify that the operation was designed to measure the pulse of the people. It was just a preliminary attempt to see if it was worth it undertaking a major operation. And the answer was “no”!

Colonel David Smiley returns to the base of the British regiment in Germany, where after two years, he learns the full details of the reasons that brought about the failure. Further, a lot was said and written about the Albanian operation, from both sides. It was described as “Radio Game”, “The Great Betrayal” and “The Cost of a Betrayal” was calculated. The operation may have been designed from the beginning, only as; “an episode of battle; in the fight against communism”, but its executioners, it took years to come to terms with the failure.

Colonel Smiley seems to have matured these successes and defeats over the years at his home in the quiet west London neighborhood, with due calmness. Now, when he is approaching 90 years old, he feels that like it or not, he is connected to the history of this country, even though the adventures with ballistic missiles and partisans are now very distant.

As he finally raises the glass of brandy brought by some Albanian friends, Colonel David Smiley tells me that he now communicates freely with acquaintances in Albania, and has even been there several times. “Now Albania has completely transformed. But it took so long”, he tells me, reminding me of the value of time, at his age. Memorie. al