By Roberto Ducci

The first part

Memorie.al / “The spark that will cause fire”. This is how he warned of the death of Enver Hoxha, the Italian ambassador in Tirana at the beginning of the 80s. In the argument with references from the developments in Albania, the diplomat of the neighboring country noted, not without concern, the breakdown of the political balance in the region, but also beyond, after the death of the dictator Hoxha. According to him, this would be a fortunate occasion, for the landing of Soviet troops in the land of the eagles and the restoration of relations interrupted in the early 60s. Thus, small Albania, for the Italian diplomat, would become the arena of major NATO-Warsaw Treaties clashes. Ambassador Roberto Ducci is considered a great name in the diplomacy of the neighboring country, whose career is connected with the most important decisions of Italian foreign policy during the years of the First Republic: from participation in multilateral cooperation to the construction of Europe , until the pacification of relations with Yugoslavia and Austria. He is regarded as one of the most brilliant foreign policy personalities of the time. (My Af.)

-Memories of Robert Ducci, former Italian ambassador to Albania in the 80s.

“I don’t intend to deal with the “merits” of Marxism-Leninism from other points of view, but I find it interesting to note how it keeps its subjects alive, exercising unlimited political power. We are reminded of this phenomenon in recent years, when we watched on television screens, the numerous funerals of members of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, in “Red Square”, whose life on earth was closed in ages ranging from seventy to eighty-five. The statutes of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union still describe that a good Bolshevik never retires from the struggle for the world revolution, to which he devoted his youth. The same is true in the Eastern European countries subjugated by the USSR.

As soon as their original “Old Bolshevik” leaders were executed on Stalin’s orders, not yet fifty, or expelled for their counter-revolutionary mistakes, in their sixties or seventies, the rule was faithfully enforced in all Eastern European countries. : Remember Janos Kadar of Hungary, Gustav Husak of Czechoslovakia, Nicolae Ceausescu of Romania. But this phenomenon has never seemed more successful than in the case of two communist rebel leaders, Marshall Tito and Enver Hoxha. Tito ruled Yugoslavia for more than forty years. Hoxha, who founded and was appointed leader of the Communist Party of Albania in 1941, still enjoys his position.

His absolute rule in Albania has successfully resisted attacks from within his party. (The conspirators were usually found dead: the most famous of them, Mehmet Shehu, had been Hoxha’s comrade and best friend and lifelong No. 2 for thirty-five years.) Furthermore, Hoxha had been able to prevent and burned, all the occasional plans and attempts, which were made against his life or his power, initiated and carried out by the Yugoslavs and the Russians. It seems that indeed, the hands of the apostles Marx and Lenin will have been on his head. But, unfortunately, no one, not even a confirmed Bolshevik, is immortal.

One day death will also call Hoxha and neither his cleverness nor his cruelty will be enough to stop him from going to the sick bed. A general mourning will be held by the Albanian people, and some will even be sincere. Fires will be lit in the mountains and old rifles will be fired in the valleys. His corpse will be embalmed and buried in the state cemetery; just as it was done with Stalin (Hoxha is the most irrevocable admirer of Stalin!). Then the noise and the cries will die down and the small Balkan country will continue to wander into an uncertain future.

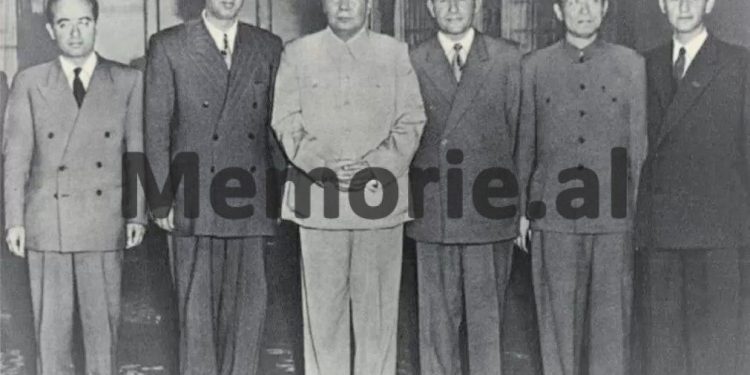

Since the end of the Second World War, Albania has been in the headlines only three times: when the Yugoslav guardianship was replaced by the Russian guardianship; when the latter were replaced by the Chinese; when the Chinese were dryly thanked for their assistance and asked to leave. In the last fifteen years, very few people in the West have known about the existence in Southeast Europe of this country, which, for all intents and purposes, might as well have been Tibet.

Self-enclosed, this country has practically no communication with the surrounding world, except through a small group of trusted officials; does not have diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom, nor with the United States of America or the USSR; he allows no opportunity for his people to know what is going on outside the world; tolerates very little foreign tourism and makes it practically impossible for Albanians to travel outside their country.

No one, not even the diplomats in the capital Tirana, who are so reduced in number that they often find it difficult to organize a table of four, so no one knows what really happens in Albania. The Minister of Defense, Beqir Balluku, was executed in 1975. Why? Because he was a Soviet (Yugoslav, American) spy? Did Mehmet Shehu kill himself, or was he killed intentionally, according to orders from above?!

Anyone’s answer to these questions, and to almost all life questions like this, is, “We honestly don’t know anything.” The interest raised among connoisseurs about any of these events quickly fades away: the map of Europe seems to no longer include the small country where, in the fifteenth century, the hero Skenderbeg led the revolts against the Turks and from where the Ottoman Empire brought out the most janissaries warriors and many of the pashalars and grand viziers.

Albania is a country with rugged mountainous terrain, slightly larger than Wales. It is bordered to the North by Montenegro and Kosovo (in Yugoslavia), to the East by Macedonia, to the South by Epirus (in Greece) and to the West by the Adriatic Sea. The Yugoslav province of Kosovo has more than one million Albanians: it is no wonder that the government of Tirana considers this number as “not re-evaluated”. Macedonia, inhabited by Serbs, Bulgarians, Turks and other ethnic groups, has traditionally been claimed by the Balkan countries; The Soviet Union, the unsanctified successor of Holy Russia, continues to entertain hopes of annexing it to loyal Bulgaria, thus driving a wedge between heretical Yugoslavia and NATO’s Greece.

Epirus also, consecrated after the souls of the ancestors, Achilles and Pyrrhus, was and is likely to become a bone of contention again, between Albania and Greece. Neither Serbia nor Greece – the two main Balkan rivals for hegemony over Albania before the First World War and between the two wars, was not able to secure Epirus completely for themselves – the inherent reason that Italy would not allow it. Italy had not allowed the Austro-Hungarian Empire to establish itself strongly in the lower part of the Adriatic, let alone let Yugoslavia or Greece do the same?

Why was Italy interested in securing an Albanian Principality under its control, or in creating a union between the two countries, in the person of the head of the royal family of the King of Savoy (Victor Emmanuel III, Emperor of Ethiopia and King of Albania, during most of World War II)? If we cast another glance at the map, we shall see that in the days of supremacy and freedom in the Adriatic Sea, as much as Venice, so Trieste, was dependent on the possession, or, at least, on the control of both coasts, Italian and Albanian, of the Strait of Otranto, which connects the Ionian Sea with the Adriatic Sea. This was also a principle of Italian foreign policy, in order to ensure that Albania would not fall into the hands of a powerful opposing state or empire.

After 1945, this principle could not be applied. Albania abandoned by the fascists at the end of 1943 and by the Nazis in 1944, entered Stalin’s empire. But after Tito’s revolt, Albania was the only advanced post of the USSR. Stalin’s descendants did not know what to do with him. Italy had other problems to solve and, in any case, its political class had been inoculated against meddling in Balkan affairs.

Rumors were bubbling and spreading here and there about the installation of a base for Soviet submarines in the Gulf of Vlora. Before the sixties, there was practically no Soviet fleet in the Mediterranean. Meanwhile, Hoxha expelled the Russians and called the Chinese. After this episode also came to an end, the government of Tirana continued to keep air and naval equipment and services from the Soviet Union, as well as from any other country.

The country remains blockfrei (Germ. free from blocks), not accepting contacts with both the Warsaw bloc and the NATO bloc. He does not even agree to be counted among the non-aligned countries, or among the neutral countries of Europe (Switzerland, Austria, Sweden, Finland and Malta); he refuses to participate in the Helsinki Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe and is not a signatory to the Helsinki Final Act. Albania lives in a self-imposed isolation: its people are too proud to surrender, too poor to feed, and to arouse greedy eyes, too brave and manly, to whatever aggression they may face. it was worth the burden of the rent, to take action against him. Albania is, perhaps, the last example of the Kleinstaaterei (microstates) of the eighteenth century, such as Weimar and Parma.

Moreover, Albania was the first application of Schumacher’s formula (British economist, famous-ed. note) “Small is beautiful” in the international field, or Shakespeare’s application of the Duchy of Illyria in the field of poetry, where Viola (character of the drama “Twelve Nights”) is loved by Orsino, who loves Olivia, who loves Viola, until everything is settled in the closing scene, except…!

Except what he might look like after the fall of Hoxha – although it’s anyone’s guess, that being only seventy-six years old, he might survive for a few more years. His advanced age, however, is a good reason for observers of the Balkan scene to start scratching their heads and, perhaps, planning what will happen when he lets go of the wheel. There is only one way to predict how the political situation of affairs and affairs in Albania will be after the death of Hoxha.

Has his successor already been discussed, in the Political Bureau of Tirana, or – as seems likely – the ruling boss, does not trust anyone, to put this issue on the agenda?! Making it known on which shoulder his mantle will fall, a dictator, very easily, builds and raises to the top a rival and, most likely, his murderer. If anyone could guess that there is a very large pro-Hoxha group in the Politburo (there is no doubt about that), this group will try to come out on top, electing Comrade X as General Secretary of The party. This scenario is acceptable, but it has a flaw: Hoxha has destroyed all his rivals, so none of his supporters, in the upper ranks of the Party, will be large enough; “to have his shadow”.

The apparently unanimous friends towards Hoxha can, for this reason, quickly divide into two or three rival groups, each under a smaller baron, and since the Albanian society is still structured in opposing clans, the political war will be able to double by rivalry for supremacy between clans. According to this scenario, the political scene in Albania could be destabilized for several years – a state of affairs that could encourage foreign intervention, as we will see. Whoever takes up Hoxha’s baton will, for a time, inevitably be more or less weak and exposed. The best course he can or should pursue, to begin with, is to preserve the status quo.

Whatever the official propaganda may say when it invents plots and CIA commandos, the leaders of Tirana know – and know only too well, that the United States has no reason to destabilize Albania. The Yugoslavs are already facing a difficult task, to drown and suppress the discontent of the Albanians in Kosovo and they would not like to annex it to its mother country. As long as Belgrade wants to protect itself from Soviet intervention, it will remain interested in Albanian stability. For this reason, the leadership of Tirana will focus on the danger of a Soviet intervention.

But is there a real possibility of a Soviet intervention in a small Balkan republic, a political or military intervention, or both? In my opinion, the answer to this question is “yes”, for reasons that are stable, both short-term and long-term. It is easy to see what advantages the USSR could derive from the return of the prodigal son to the Warsaw Pact (Albania was the only member to leave the Pact of its own free will and without suffering any reprisals). .

The restoration of Soviet influence in Albania would create the opportunity for Moscow to exert pressure on Yugoslavia, encouraging the Albanian irredentism of Kosovo and taking the role of arbitrator for the claims of the two parties. Greece’s alliance with NATO, already weakened by its conflict with Turkey and by the orientation and tendency of Andrea Papandreou, in terms of the policy of non-alignment, could be further weakened.

The Albanian ports (Durrës, Vlorë, and Sarandë), coveted so much and for so long, could be opened to the Soviet Mediterranean Fleet, which would use them for repair, service, landing, supply, and defense purposes others, because it has no facilities and infrastructure in the Mediterranean, except to a very small extent, in Latakia, in Syria. Furthermore, the annexation of Albania would allow Soviet forces to install electronic surveillance equipment covering most of the Mediterranean region, including central and southern Italy and the islands. of it, as well as the entire land area and the islands of Greece. Reconnaissance and attack (shooter) aircraft could be based on modernized airfields with underground hangars: the defense plans of NATO’s southern wing command would have to be fundamentally modified.

Finally, only extreme measures by NATO could prevent the USSR from installing tactical nuclear missiles that would be aimed at Italy, Yugoslavia and Greece. These three countries are now threatened by “SS-20” type missiles, as well as by other types of missiles, but the placement in Albania and the use from there of short-range missiles – and therefore even faster – will added yet another difficulty to the complex problem of dire threats to the Southeast European region, which, even in today’s state, is not well-defended. The advantages that the Soviet Union could reap, by returning Albania to the Warsaw Pact, are so obvious that, surely, the matter must have been studied in closed circles, in the Council of Defense and in the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

The risk of conflagration, a very serious crisis with the West, was certainly obvious and great in such an assessment. Taking military action against Albania might seem like a very bold decision, exactly in the order of the decision Khrushchev took to install missiles in Cuba. The potential benefits, however, could outweigh the difficulties. The greatest among the latter was the lack of land continuity between Albania and Bulgaria: the use of land forces, at least in the initial phase, would have to be ruled out. But paratroopers and airborne troops could easily capture the Adriatic ports, with a perspective that would hermetically seal these ports against a possible landing of NATO forces.

Astonishingly, airfields would also be captured and an airlift would be established for logistical supplies in a relatively short time. I will not continue to cover war games, which I am not at all competent at. Instead of this course, I will try to describe a possible political scenario that would justify the operation “Albania”. In a speech at the Conference of Non-Aligned Countries, the late Indira Gandhi made an unexpected statement, according to which her country could feel sorry for herself one day, therefore; “It is completely normal and in the order of things”, she said, – “for the government of a country to ask for help from an ally or brother country”.

What Mrs. Gandhi had in mind, of course, was Afghanistan: she was thus trying to legitimize the Soviet armed intervention there. With this blow, other military aggressions by the Soviet Union, against “brotherly” countries, such as Hungary and Czechoslovakia, would be legitimized. It was perhaps the best tribute, to the memory of Leonid Brezhnev, who invented the doctrine of “fraternal aid”, which would be a reason for military intervention abroad, with such scenarios, where a socialist country is usually described as being loses its independence and revolutionary heritage, due to the maneuvers of treacherous gangs against the proletariat, in conspiracy with the Western imperialists.

It is arranged that a handful of insurgent heroes rise up against this hidden plot and seek the help of the Soviet Union to break and crush it—a request that Moscow honors generously, in the spirit and spirit of revolutionary internationalism. In this scenario, Soviet planners have already reached a point where two of the main elements of the “Albania” operation have passed the feasibility test: an air strike and landing against Albania would not be such a big deal, for air and ground forces. Memorie.al

The next issue follows