By Sven Aurén

Translated by Adil N. Bicaku

Part nineteen

ORIENTI EUROPE

Land of Albania! Let me bend my eyes

On thee, thou rugged nurse of savage men.

Lord Byron.

In the book “Orient of Europe”, the author of the work is the Swede Sven Aurén. They are impressions of traveling from Albania from the ‘30s. His direct experiences without any retouching.

In a word, the translation of the book will bring to the Albanian reader, the original value of knowing that story that we have not known and we continue to know it, and now distorted by the interests of the moment.

Now a little about what these lines address to you: My name is Adil Bicaku. I have worked and lived for over 50 years in Sweden, without detaching for a moment, the thought and feeling from our Albania.

I am now retired and living with my wife and children, here in Stockholm. Having been for a long time, from the evolution of the Albanian language, which naturally happened during these decades, I am aware of the difficulties, not small, that I will face, to give the Albanian reader, the experiences of the original.

Therefore, I would be very grateful if we could find a practical way of cooperation together, to translate this book with multifaceted values.

Morally, I would feel very relieved, paying off part of the debt that all of us Albanians owe to our Albania, especially in these times that continue to be so turbulent.

With much respect

Adil Biçaku

Continued from the previous issue

THE CITY NEAR SHKUMBIN

Early in the morning we take the road to Elbasan.

The curves of the road, climb like snakes up the mountain in gray paint, curves and twists, get lost and come out again. A cloudy line floats slowly and reveals a splendid, folded alpine peak. Like the thorny ridges of ancient mystical animals, four strings extend one after the other. The last one there got a light color in front of the horizon, a lighthouse painting with a blue spray. It’s the Adriatic.

Our car moves forward in this fantastic mountain nature, where there is no man, no house that can be imagined that we travel to a habitable place. The giants, raised like giants, look menacing on the street corners. The ravines are dark wells, from where you can see the high blue sky up there. The abysses are surprising, unexpected and dizzying. We dive into a turn, like a pin with a speed that the rear of the car, will meet at the corner of the turn. We come around a giant rock and rub next to it, the mountain path to escape, to continue straight into eternity. It seems to us, that we are doing an act of balancing at the top of the Eiffel tower.

I begin to understand something of the secret of Skanderbeg’s success. There across the west, hangs a castle ruin on a cliff edge. It was once an important part of the network of fortifications that the strategist from Kruja sought to spin on Albanian soil. How could the Sultan’s forces cope with such defensive acts? Conquering such a castle costs blood, time and money without end. And when the invasion was over, what did he gain from all that suffering and hardship? Exactly nothing.

This winding road from Tirana to Elbasan was built by Italian engineers and formerly Italian. It is a masterpiece in its range. The difficulties in its construction have been excessive, the colossal cost. Do you believe that it was built for the good of Albania? Why should the poorest country in the Balkans have the strangest serpentine in the Balkans? He gets the answer to this question in Rome.

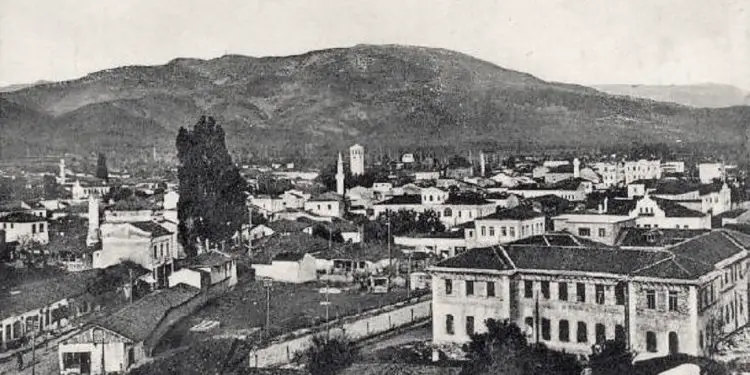

But Elbasan is worth a visit and this record Italian road, a dangerous and dangerous car ride. Elbasan is an important city, of spiritual importance. It has 10,000 inhabitants and lies in the geographical middle point of Albania. For some reason not yet explored so far, all the country’s intelligence, mostly, has been recruited from this city. Most Albanian students who study at universities in Vienna, Paris and the USA come from Elbasan. The city has wonderful schools, a school for teachers and a characteristic intellectual life. There is even an academic club there.

This situation, that Elbasan lies in the middle of the country, has a special demographic and philological interest. With the exception of a minority pair, Albania consists of two large population groups: the Ghegs in the North and the Tosks in the South. The difference in behavior and language between these groups of the population is quite, if not so deep, that I often want to emphasize: Elbasan is located in the middle of the Greek-Tosk “border”.

Based on this demographic heterogeneity, the difficulties of creating an Albanian written language have been colossal. The political situation has also taken its toll. The Turks tried for five hundred years, in every way to prevent the publication of a literature in the Albanian language. That written language, which in spite of opposition, was opened and developed, remained in fact poor and not unified. In the south of Albania, the youth learned to write in one way, while in the north of Albania, in another way. In addition, it seems that there has hardly been any agreement between the different opinions, of the teachers, even within these two parts of the country.

Efforts to unify and enrich these languages with different scripts were not lacking, but the efforts were not crowned with any success. In 1906, a language commission tried in Bitola to eliminate these troubles and introduced, among other things, the Latin alphabet, but it remained unsuccessful. A literate refugee colony in Bucharest smuggled books written in Albanian to guide the youth. After the declaration of independence in Vlora in 1912, work began again with the language problem. This newly gained freedom brought waves of national joy to the skies, among the inhabitants of the Adriatic coastal city.

Everything would be reformed and improved, but these advances would not be made soon but immediately. An independent state should have a written language that was a natural thing. So let’s start creating a written language! Said done. Seven honest men started it with the best of intentions, as members of a hastily established “academy of literature” and began work. None of them could write a letter at least, without three errors in each sentence, but what was missing in the knowledge, was devalued by patriotism. Those seven members of the academy, proclaimed a call according to which the intellectuals of the city, as foreigners as Albanians, to send proposals for new words.

The inhabitants of Vlora felt that at this moment it is an honor, which extremely rarely overcomes any person, that you can create a new language. They wrote and wrote, borrowed and fantasized and after a short time, the masters of the academy were almost drowning in those thousands and thousands of words, proposed. But it would be a sin not to give to the energy of the academy, great thanks for the merits. No less than twenty-seven public service appointments were recreated from the trunk alone. They also fabricated Albanian loanwords. ‘Consul’ became ‘Kortsul’, ‘franc-maçon’ (mason) ‘far-mason’, ‘influence’, ‘flux’.

Then those seven members of the academy must also and especially, are affected by a long paralysis. However, all that great commitment was poured into the sea: academy, written language, immortal dream. For the first time in 1916, written language became a reality. It was built on the basis of Greek-Tosk Albanian, like the one spoken in Elbasan. And now, therefore, it is possible that, twenty years ago, it would have been an absurdity: that resident of Shkodra, who knows how to write, could send a letter in his own language, a resident of Saranda, in the south, understand and get an understandable answer.

This small, dirty, economically insignificant city, Elbasan, has played an important role in the spiritual life of the country. Elbasan has supplied intelligence, created schools and teachers, formed the basis of the successful language commission of 1916. Everything together has given the city an extraordinary name.

When an Albanian encounters a stranger outside in the forest or field, he asks: where are you man? And in this question, with strange wording, hides a curiosity as to where the stranger comes from and where I am going.

-I am a man from Dibra, the other answers, if he is from that province: I am a man from Dibra, on the way to Kruja. This answer contains a lot of pride and is of great importance. Dibra has a great reputation, in terms of courage, bravery, military services. If the stranger was from Elbasan, then he says: I am from Elbasan and this is an answer, which arouses respect. Imagine for a second you were transposed into the karmic driven world of Earl. But this does not mean that he would be weak. Even the men of Elbasan are rightly proud of their bravery. Only the meaning of the name Elbasan, “triumphant place” shows that the city near Shkumbin, has understood to protect his freedom and honor, in a way that Albanians have for honor.

The city of Shkumbin… down there, the silver bar of Shkumbin is already shining. The car crashes into a very strong turn of the serpentine and suddenly, the brown mountain is avoided, to make way for a wide and light green alpine valley. In the middle of the valley, the wide Shkumbini flows and shines. Olive groves, in gray velvet and hundreds of years old cypress, break the monotony of the green field. Across the sharp tops of cypresses, I see white, low houses and the sharp spears of minarets.

The road leads downhill and in front of a reception, of a glass of cold brandy, the driver drives the cart so fast through the slopes that the cityscape seems to be magnifying in dimension, every second. The houses differ from each other, slightly roofing and gates. The minarets immediately widen, below the spear, and the round balconies of the seniors appear to call for forgiveness. The contours of the eyelids become thorny, rarer. Black dots rise above the ground and take the form of loading humans and animals. Shkumbin sees the bridge and the water swirling with abduction.

Elbasan!

Now we will enter the city of Albanian intelligence. The word is shock. The roads are potholed, muddy, broken; the car is thrown here and there, like a boat in a storm. The little houses, which now look white, like birth tales, are in dirty gray and with walls sunk by fatigue. But it is the destiny of philosophers, to dwell in this surroundings, which is an improper contrast, to their beautiful thoughts. Already the contrast between the external and internal appearance of the birth philosopher, is usually of a rather macabre form. The society in which philosophy resides is precisely in a longer sense of thought, only a part of the external figure and Elbasan, fits well in this style.

No, this is not a beautiful city, so they rightly call Tirana: a poor Balkan village. Despite the cultural contribution, refreshing smells do not blow here. People seem indifferent and submissive to fate. They sit in their laps and beat lazily, in the workmanship of silver, or give shape, without work enthusiasm, to sheepskin coats, around brown mud molds.

This foolish melancholy behind the melancholy donkeys, or stand and guard in front of a torn tombstone in the courtyard of the mosque, in front of a piece of mirror. An imam is sitting cross-legged in a corner and taking a sip from a glass of brandy. Owners of meat shops in the sun, deal with flogging with killer flies, shoulders and ribs of hanging meat. A woman covered in white, takes off the high-heeled shoes, of the old Viennese model, to pass through a turbid water pond, which has blocked the road.

Ah Elbasan, your beautiful name is a cruel joke!

Slowly we lean forward between the cracked walls and the dead houses. A great one reminds us from the crown of the minaret, that Allah is great. No one pays him any attention. No one bows his head to go to the mosque and bow to Mecca, as instructed by the Prophet. Everything is without blessings, a great apathy. Very rarely, this ugly village will be able to stimulate intellectual inclination! Or maybe it will be so, that those intelligent men from Elbasan do not see fit to try to keep clean in front of their door, but prefer to dedicate their talent to the service in Tirana? So it is of course.

For the first time in an open place in the corner of the city, shines a little, this gloomy figure of the city. Here is shopping with push, life and movement. The villagers went downstairs, with their products, and lined them up for the ground. Above the makeshift crates on the counter, you see piles like mountains of cheese and eggs, tobacco, grain and cloth, hand-knitted at home. The animal skin trader wears as an advertisement one of the sheep skins, prepared as a cape.

Women talk non-stop, behind veils and shout at passersby. Men with white scarves and black jackets, with puffy wrinkles, have their own story. In Skanderbeg’s time, all men in the provinces around Kruja wore white jackets. After the death of the freedom hero, he dyed his black jackets and thus, this paint became a custom and a tradition. Any Albanian you ask, give this explanation. But the strangest thing is not the explanation as such, but the unwavering belief in its truth. Who has the courage to question tradition?

After some hours wandering in this city not fascinating, we paid a visit to the prefect, because such a visit, is the first obligation of a foreign tourist here. The prefect was seen as all the other prefects we would later encounter: an overly polite gentleman, an unfurnished sea per room, where King Zog and Skanderbeg doubtfully look at each other, from the frames of florinjta. An interpreter, who mediates the conversation, because the mayor speaks only Albanian. A conversation that explores the topics of Albanian nature and Albanian progress. And so, of course, sweet coffee, miniature cups and coated plums, with powdered sugar.

-Mr. Prefect, your country has a wonderful nature which is an experience, get in touch with it!

-Dear sir, it is a pleasure for me to hear your kind words. My country is beautiful, but it’s also a progressive country. The monarchy is only eight years old and what we have not accomplished! Roads, schools, industry, new buildings…! Memorie.al