By Najada Pendavinji

The first part

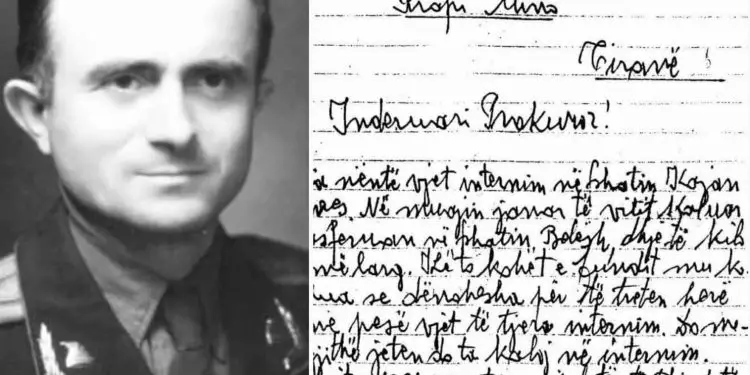

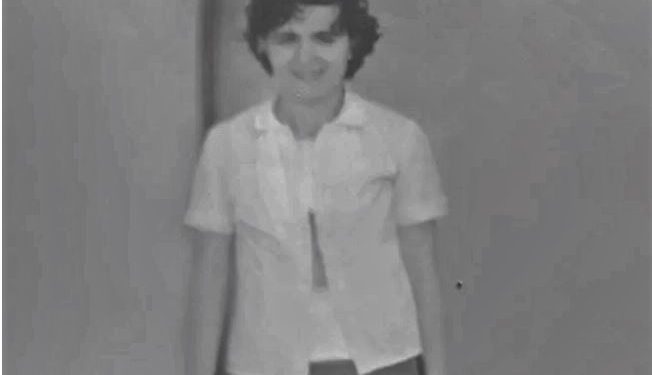

Memorie.al / She were 14 years old when her father, Colonel Dilaver Radeshi, a well-known military historian, was sentenced to 10 years in political prison. After those ten difficult years, another period of revenge against the indomitable soldier’s family began, where the biggest test was passed by the eldest daughter, Tefta, who for days was subjected to the exhausting investigation, headed by Nevzat Haznedari. Those questioning sessions were so unbearable that the young woman tried to kill herself. Today she is over 70 years old, lives in the city of Korça together with her husband, Vaskë Kolaci. With the desire and passion that characterizes her; in 2005 she finished her studies at the Faculty of Economics with excellent results and is an important voice of her community in protecting the rights of the politically persecuted and different layers of society. In this interview, she tells in detail the sufferings of her family that started in 1966-’67, when they condemned her father and continued throughout the communist dictatorship, until 1991.

Ms. Tefta, what did the figure of your father, Dilaver Radeshi, represent?

I am Tefta Sulçe Kolaci, the daughter of the historian and former soldier, colonel, Dilaver Radeshit. Telling you about my father is a strong emotion for me. In our house, we have fanatically preserved every article in a newspaper or magazine that has mentioned his name and history. We have always read about him, about his life, about what he represented, but we, the children who live with his memories, have never talked about the figure of our father Dilaver Radesh. Perhaps because our narrative would be dominated by subjective experiences and perceptions and this is more than natural since, for a child, the figure of the father is always symbolized with the figure of the hero.

My father Dilaver Radesh was born on January 10, 1922 in the village of Radesh in Skrapar. His character was known in the National Liberation Movement, where he was characterized by his patriotic and patriotic spirit. In the wake of his activities comes the inclusion in the ranks of the First Assault Brigade where, during the fighting, he was wounded three times. Later in the war for the Liberation of Tirana, at the “Palace of Brigades”, the father would be wounded for the fourth time. Nothing stopped his will, a will that we inherited from his children. Even after the liberation of the country, the dreams and desires he had would continue. So in 1945, he went to the Aviation School in Belgrade, to fulfill one of his passions, which was piloting, but he could not, due to the wounds received during the War, where he was declared a war invalid.

In 1946, he was sent to study in Odesa, at the military school in Moscow. He returns from there as an excellent student and is appointed commander of the honor guard. His presence as a soldier, his brave appearance attracted attention in the ceremony of receptions and escorts of delegations. His voice was strong; it had the purity and warmth of the mountains of his homeland. Voice, which still rings in my ears with an openness and love that he taught me about life and human values. In 1956-1958, he continued his studies at the High Military Academy “Frunze”, for Military Art in Moscow, where he was awarded a gold medal.

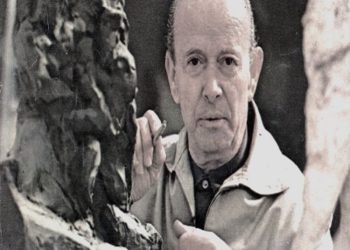

Now he was an educated man, studied abroad who, despite the communist country where he finished his studies, had a pure intellectual spirit, where he read, translated and published mainly books about the history of Skanderbeg’s wars, such as: “The Battle of Torviolli”, ” The Battle of Drin and Oranik”, for which he dug and searched all the way to the archives of Istanbul and Rome. Also in the Military Magazine, he published studies on the Albanian military art for which he had studied and worked hard and other events and studies from the National Liberation War. He wrote his book “The Incursion of the First Assault Brigade”, published in 1963.

Studies and books that my father wrote that were published in several journals disappeared immediately upon his arrest, but continued to be part of the Archive. All these publications, studies, materials which could not be compiled as separate publications, we have sent to his children (after his death and decoration by the then President Alfred Moisiu) to be published at the Defense Academy – Department of Military History, by Professor Proletar Hasani. I’m sorry because even today those publications with studies which he realized with great passion have not been published. A passion that he would continue with the study of the figure of Skenderbeu even after 6 years from his release when he would pass away on his work desk.

How did he get arrested and sentenced by the communist regime?

The father was an educated man with the spirit of justice. At the time when the communist government began to follow a different course in the army, directed towards Chinese politics, my father Dilaver Radeshi, in 1963, returned in the form of an opposition against this course. His studies, the knowledge he had in the military field, did not allow him to accept the “Chineseization” of the army.

What happened after this opposition that he was doing?

Father was one of the military men who openly opposed military reform and its degradation, opposed the abolition of ranks and dared to propose a change in the line of the Labor Party in relation to military defence. He openly expressed his thoughts in a letter addressed to Enver Hoxha and two other figures, Beqir Balluku and Mehmet Shehu, in which he argued the ideas and changes. This open letter was revealed in the political trial that took place on February 27, 1967, from which the father, Colonel Dilaver Radeshi, was first arrested “for treason against the motherland” and sentenced for “agitation-propaganda” to 10 years in prison.

In that trial, they put many labels on the father, such as “rebel”, “dissident”, “enemy”, “traitor”, but the most important one was called “residue of the Tirana Conference”, held in 1956. All these did not they made an impression. Father’s trial was a closed-door trial and we his family knew nothing of what was going on. But I remember that, when my father came out of prison, he showed me, among other things, some sequences of the trial. He told me: “During the decision, the prosecutor stood up and told the other soldiers participating in my trial: ‘Stand up…! What do you think about this opponent?! Grave silence. This gave me the courage not to give up my thoughts.”

This gave him the strength not to surrender to the serious accusations of the communist dictatorship. He managed to challenge the Enverist politics, not saying “black is white and white is black” as servility towards the party demanded. He was never defeated, not even in the interrogator where he stayed for 6 months and it is known that in the dungeons of the interrogator, people were alienated by the inhumane torture used by the investigators of the State Security.

What happened to you while your father was serving time in communist prisons?

Like any family that had a member convicted by the communist regime, we, the family of Colonel Dilaver Radesh, would be targeted by the State Security. Every day, the shadow of doubt and fear danced over us, what would happen to my father’s life? What would happen to us, his family? What fate awaited us? At that time I was only 14 years old, while my sisters and brother were younger. Mother, Lumturi Sulçe, raised us with a sad heart, but she nurtured us with love for life and people. We were walking a long and very difficult road.

The persecution of us would not begin with the imprisonment of our father, but it would come slowly and permeate every cycle of our lives. So during that time, they did not remove us from the place where we lived, which was Tirana. We continued the flow of life, working hard with the hope and belief that our father would join us as soon as possible. Mother guided our lives, easing the pain and absence of father. She worked in a permanent, where she had to serve every customer.

Regardless of the status we had, mother was seen by everyone as a brave woman. A woman who kept her family standing, standing strong in the face of everyone despite the blow we suffered from the strange fate that engulfed our lives. We children continued school. After finishing school at “Partizani” gymnasium, I used to go to my mother’s work and get the perm wipes, take them home where I washed, dried and ironed them. From this job I earned something that relieved my mother a little of the expenses. We had grown up with the spirit of education and work.

Did you meet your father in prison? What were the vicissitudes and sensations you experienced in those meetings behind the iron doors?

The moment of his arrest, appearing in front of the political trial, staying in the investigator’s office for 6 months, the prison sentence, we as his family had no idea about all this until the moment when a telegram came to us from the father, with the clarification of only that he was serving his sentence in “Prison 313” in Tirana, where he stayed for a very short time.

We all left as a family, my mother, me, my two sisters, Violeta and Irma, together with my brother, Kastriot, towards the prison where we took blankets, mattresses and food, the things we thought were needed. When we went there, father was behind two pairs of bars, which made the distance between us and him too great. His hands and ours reached out through those cold bars, to feel the warmth that only a father’s strong hands could provide. Our eyes were very sad. We had not seen him for a while; it was enough for us that he was alive. This was the first meeting with him, with the father.

We already began to understand and feel that sharp knife of the dictatorship in the chest which sometimes left you breathless. After two months, he was transferred to the Cement Factory in Elbasan. Here too we tried to have a meeting with him, but now only my mother and I would go. We prepared for the things we were going to take, we started knitting woolen clothes to keep him warm, we cooked the food he liked and we set out to meet him. That day it was raining heavily and continuously and the train we both took left us half way. We walked through the slippery mud, carrying our bags of food and clothing high up on our shoulders to stay clean.

By the time we got close to camp, our feet were frozen and the mud could hardly be removed. Just like this “mud” that had covered Albania. I was so frozen that when we met my father, I couldn’t speak a word. We just saw each other. Later on January 8, 1968, he was taken to Spaçi prison camp. All those who suffered punishment in this camp, but also those family members who went to visit their relatives, know very well the pain caused by this infamous camp. Spaçi gave you a scary feeling; I remember that it was like a black hole, a very difficult and distant road, where we always went together with other families who had a family member sentenced to that camp.

Where I can mention: the family, mainly the mother Emilia of Vangjel Lezho, who was later shot, with the aunt Lolo of Xelal Koprêncka, etc. From this camp, my father told me that there were moments when they tied his hands with wire, tightly pressed behind him in a chair, and when they took them off for personal needs and tied them again, it was torturous also because of the wounds he had on body, but never screamed. Also, from the dungeon where they put him, he encouraged the prisoners to go to work, while they returned to him: “How could Mehmet Shehu not win in the First Assault Brigade with such brave “fools”?! In the years 1971-73, my father would try another camp, that of Tepelena. For him and for us, this camp was difficult.

I remember the obstacles and vicissitudes we encountered during the journey to this camp to meet my father. The bus driver always left us at the end of the road, even though he passed near the Bencha Bridge, where my father was imprisoned, where we had an easier time crossing. But no, he could not agree to help a family that was going to visit the “dissident”. Also, I cannot erase from my memory the moments when, on the road we passed, women and children were waiting for us, throwing stones at us and calling us “enemies of the people”.

This was the class struggle. A war that fueled hatred and contempt. The meeting with the father was strange. He was in a small room that had a barred window through which only sound could come. This meeting left a big void in our hearts. After some time, the father would be taken to the Burrel prison where he would finish his sentence, in one of the most brutal prisons of communism. Even Burrel had a scary appearance; he was cold, icy, giving you the feeling of “death”.

When did your internment that of Dilaver Radesh’s family, begin?

Years passed and our journey in the dictatorship would continue with its own nightmares. It was 1977, the year that also marked the release of my father from communist prison. We had dreamed of this day. At that time, only the mother and the younger sister, Irma, went to the Burrell prison. They waited for hours, but from that gate of that infamous prison, it was not the father who came out, but an officer with a wild expression on his face who told them: “He is not here”. No other explanation. This answer would be trouble for us. They returned full of doubts and with an empty soul!

After a few days, we receive a telegram from my father. They had exiled him to the village of Kajan in Elbasan. The one who had ordered the exile was the master torturer, Nevzat Haznedari, who, together with Vangjel Kote, asked his father to testify against Beqir Balluku, Petrit Dumes, Hito Çakos, figures who had taken a tough stance against the convictions of him, when he was convicted in 1967. The father refused to testify and his words were these: “I attacked them when they were in the chair and the highest functions and now that they are bound in irons, they are being attacked by “street dogs”, they are my friends and brothers, even when they come to prison, I will give them a cup of coffee”!

So he was sentenced to deportation, after he did not sign the declaration of cooperation with the State Security. An isolated exile that continued until the early 1990s. Here, then, after my father’s exile, our persecution by the two formidable figures of the time, Nevzat Haznedari and Vangjel Kote, begins. They understood that this “rebel” should be touched at the weak point, which was his family. So began our confrontation with the investigation, with the persecutions by the Security spies. They followed us everywhere. They wanted to put us through the paths to lose our human consciousness and awareness.

Ms. Tefta, how did the story that led you to the suicide attempt continue?

Every time I’m asked to talk about this part, I wander in my thoughts, and every time I go back to it, I discover new details about the condition that led to my suicide attempt. It all started when we were under a lot of pressure from the State Security. I was the eldest daughter in the family and both Nevzat Haznedari and Vangjel Kote took care of me. My character was very similar to my father’s. I have always accompanied and helped other persecuted families who had their relatives in communist prisons. This was also pointed out by Sigurimi, who, with the paranoia that characterized him, raised doubts.

During the time that my father was interned in Kajan of Elbasan, there was an investigator who justified their crimes against us. First, it was the mother who would be called to the interrogation room, and then I. They didn’t deal much with the mother, but they would conduct an investigation against me that would last for almost a month. It was a senseless investigator as they called me one day yes and two days no. It was exhausting the thought of when the next turn would come to try again that gloom that the investigator of the time would give. The first encounter was terrifying. It was a room with dark walls that gave the impression of a cold tomb where the interrogator asked provocative questions that the mind could not conceive.

I have faced several investigators of the Security, where I can mention Skënder Sevastani, but the most inhumane has been and will remain Nevzat Haznedari. This situation would continue until the moment when I would go in front of the car of Kadri Hazbiu, (the Minister of Internal Affairs at that time), with the courage of a girl who had been overcome by boundless sadness. It was 5:00 in the afternoon when I closed the day of my trial at the inquest. In the yard in front of the Ministry, Kadri Hazbi’s car was passing. At that moment, I ran and jumped on top of his car. Out loud, I declared that if they called me again, I would kill myself. Maybe for the moment it was a statement made in annoyance, but which I would put into practice…! Memorie.al

The next issue follows