Memorie.al / It were the autumn of 1983 when the journalist Javer Malo, then head of the Committee for Foreign Relations, knocked twice on our door. He was interested in meeting my father, but it was impossible, as he was seriously ill and could not receive him. I immediately briefly conveyed the purpose of Javer Malo’s visit to my father: The Italian Ambassador to Tirana, Gentile, Neapolitan by origin and passionate about history, had been informed by Lefter Dilo, director of the Gjirokastër Museum, that Vangjel Meksi, Ali Pasha Tepelena’s doctor, had graduated in Naples. The curious Ambassador inquired at the University of Naples to verify it, but they asked for the years of schooling. My father, though sick, after hearing me without opening his eyes, uttered: 1803–1808.

A month later, a few days after my father had passed away, Javer Malo came again, this time to convey the Ambassador’s thanks, which had meanwhile gone once more to Naples and finally found Vangjel Meksi’s name, specifically in the register of 1803. Years earlier, the Patriotic-Cultural Association “Odria,” after learning about the life and works of Dr. Vangjel Meksi, our distinguished fellow villager, asked the Academy of Sciences to organize a scientific session dedicated to this not-so-well-known personality of the early 19th century. On this occasion, academician Dhimitër S. Shuteriqi, Prof. Dr. Xhevat Lloshi and Dr. A. Omari presented their scientific studies, which were published together in the book “Dr. Vangjel Meksi (1770-1823) personality of the Albanian language.”

ALI PASHA TEPELENA’S DOCTOR

Vangjel Meksi was born in Labovë around 1770 and served in Ali Pasha’s army as an artillery officer, after completing the “Zosimea” Gymnasium in Ioannina. His family, the Meksaj of Labovë, was a famous family and friends of Ali Pasha Tepelena. The Pasha knew their tradition in practicing folk medicine, which is why he chose Vangjel to send him to Naples to graduate in Medicine. On February 23, 1803, the future student crossed the Adriatic, firmly holding the Vizier’s recommendation for Ferdinand I Bourbon.

The Vizier of Ioannina wrote to the King: “I am sending you Vangjel Meksi, the Albanian, to study there. I ask Your Majesty to be kind enough to grant him your royal protection, so that he may enjoy those conditions and facilities that lead to the learning of these sciences.” Less than five months later, showing his special interest, Ali Pasha wrote to the King of Naples again:

“I send you the most distinguished thanks for everything that has been given to Vangjel Meksi, who I hope will benefit from the conditions generously created for him by the Sovereign, and when he returns to the Homeland, with the appreciation for good conduct and the acquisition of knowledge, he will elevate the name of the glorious King.” (For the first time, these letters were published by G. Monti in “Rivista d’Albania” in 1941, II, p. 48-50.)

During his schooling, Vangjel Meksi was treated as an officer and had the distinguished doctor and chemist, Nikola Akuto, as his teacher. He performed his clinical practice at the San Giovanni a Carbonara hospital. After returning to Ioannina, Vangjel worked as a doctor near the Pasha. Together with three others, Metaksai, a graduate of Paris, Saçellari of Vienna, and Lluka Vaja, the brother of Thanas, the chief commander of Ali’s army, a graduate of Leipzig, they formed the Vizier’s medical council. Ali with Vangjel, a graduate of Italy, now old and sick, had doctors in his court who represented the most distinguished medical schools of the time.

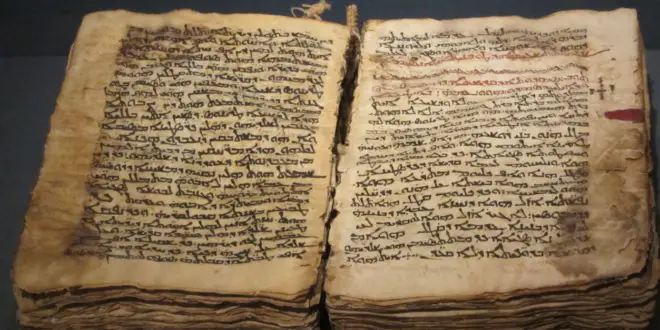

THE FIRST TRANSLATOR OF THE NEW TESTAMENT

While practicing the profession of doctor in Ali Pasha’s court, Vangjel Meksi was part of his inner circle. Precisely during this period, he met the French consul, Pouqueville, as well as the famous English travelers, Leake and Byron, who were authors or publishers of Albanian language grammars. “Ali Pasha Tepelena’s Ioannina was a fertile garden of Albanian grammars” (V. Meksi… etc. p. 15). Vangjel Meksi lived, worked, and was nurtured in this garden.

He valued his mother tongue and had begun to study it. Initially, he compiled an Albanian grammar. Robert Pinkerton, the representative in Istanbul of the London Bible Society, informed the society that Vangjel Meksi had been recommended to him as the only person who could translate the Testament, since he had been involved with Albanian for a long time and notes: “He has already written a grammar in his native language, which he showed me.”

It is likely that “Meksi’s first work was this grammar, also prepared for teaching Albanian in schools” (Jup Kastrati. History of Albanology. I, p. 516). About Meksi’s grammar, it is only known that it was published before 1819. In this way, it may be the first or second compiled by an Albanian scholar, after that of E. Vithkuqari, (1814), sponsored by Leake and perhaps compiled together with him.

Also during this period, Vangjel Meksi compiled an original alphabet, as well as the book “Orthography of the Albanian Language.” The alphabet contained Greek letters, but also Neolatin ones to somewhat eliminate the phonological differences between the two languages. For sounds that could not be represented by Greek letters, Meksi borrowed letters from the Neolatin alphabet, such as: d, b, e = ë, etc., or used combinations of letters, as well as diacritical marks in the form of a dot above the letter (V. Meksi… etc. p. 46).

Now the picture is complete. Vangjel Meksi studied his own language, compiled the grammar of the Albanian language, determined the alphabet and orthography, sought and found the necessary words to solve the difficult tasks presented by translation, and left Ioannina in the direction of Italy, where he did the general rehearsal before his major work. Thus, in 1814, he published in Venice two translations from the French writer Claude Fleury (1691–1720).

Now with a perfectly completed CV, he returned to the Balkans. In Thessaloniki and Istanbul, he met with the representatives of the English Evangelical Association with whom, on October 19, 1819, he signed the contract for the translation of the New Testament, the first point of which literally states: “Dr. Vangjel Meksi pledges to translate the New Testament from the ancient Greek text into the Albanian language, as spoken in Ioannina.” (V. Meksi…etc., p. 18).

The book, already translated into Albanian, was submitted for printing only after 15 months and specifically on February 22, 1821, 10 months before the date set in the contract. The full publication of this work, which was valued by all scholars as an important event in the history of our language’s writing, was the first in the Balkans and was realized 2 years before the Bulgarian publication and 20 years before the Romanian publication (Jup Kastrati, “History of Albanology,” 2000, p. 519).

NEGOTIATOR IN THE GREEK REVOLUTION

Vangjel Meksi participated in the Greek revolution. He thought, just like Naum Veqilharxhi, who fought against the Turks for the liberation of Romania, that only in this way would the liberation of Albania be accelerated. During this period, he fell ill with pneumonia while following the actions during the siege of the city of Tripolitsa in Northern Peloponnese. The city was defended mainly by Albanians mobilized by the Turks, while Albanians united with Greek insurgents attacked from outside.

Vangjel Meksi certainly served as a doctor for the attacking forces. Finally, both sides came to an agreement and avoided further bloodshed. In this way, the besieged abandoned the city, along with their armaments. The Labovites, participants in this war, spread the news that is also known by today’s Labovites, that the agreement was reached thanks to the intervention of Vangjel Meksi, through the Albanians fighting in both armies. A few days later, the Labovite, the doctor, the linguist, the Albanian translator, and the freedom fighter died. It was 1823.

THE DISTINGUISHED LINGUIST

The Bible Society published a part of the New Testament, the Gospel of St. Matthew, in 1824. During 1825, through their agents, the impressions of Albanian believers wherever they were were gathered, and they unanimously answered that their pleasure was great whenever the Gospel was read in their mother tongue. Moreover, the priests were also eager to place Albanian in the churches (V. Meksi… p. 28). Following the positive responses of the believers, preparations for the full publication of the Testament began at the end of 1825.

In addition to the representatives of the Bible Society, Grigor Gjirokastriti, a high-level cleric and intellectual, the former Archbishop of Euboea, who spent the last months of his life as Archbishop of Athens, was also in Corfu, the city where the holy book would be printed. While in Corfu, he dealt with the literary correction and editing of the material.

The last sheets of the book finished printing in August 1827. It was 839 pages divided into 2 volumes. The division into 2 volumes was made after the insistence of Grigor Gjirokastriti, since, according to him rightly, “Albanians are accustomed to carrying books in their bosom.” The New Testament translated into Albanian by Vangjel Meksi was republished in 1858, and the last copies continued to be sold until 1878.

Thus, this book was sold for 50 years, to be used for several more decades. This data confirms the extraordinary success of the book, which was based on the elaborate, rich, and accurate language, adapted to the idiom of the Albanians, on the choice of words and expressions understandable to all, as well as on the original alphabet, which respected the phonetics of our language very well.

THE FATHER OF THE ALBANIAN ALPHABET

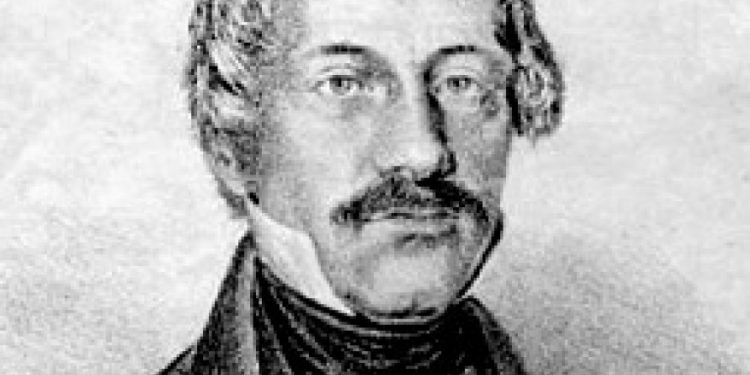

After the publication of Matthew (1824), but especially after the full publication of the Testament (1827), the interest of the philological and cultural opinion, in Albania and abroad, began for Meksi’s Albanian translations, considering them; “as efforts for the written Albanian literary language” (Vangjel Meksi… etc. p. 36). The German scholar Xylander (1794-1854), who first argued the Indo-European character of Albanian, published the book in 1835; “The Language of the Albanians” based mainly on Vangjel Meksi’s Albanian translation.

He took a step forward compared to previous scholars of the Albanian language, only because he had a wide text in the Albanian language, the New Testament, in his hand. Xylander affirms that; “with this translation, the time of doubt and uncertainty ends for the Albanian language as well” (V. Meksi… etc, p. 38). Hahn (1811-1869), the father of Albanology, concluded that Albanian is the continuation of one of the Illyrian dialects, thus becoming a defender of the autochthony of Albanians, only after learning Albanian, mainly, through Vangjel Meksi’s New Testament.

Meksi’s original alphabet was used in Albanian writings of the 19th century, including those of Xylander and Hahn. For this reason, Meksi has been called; the father or conveyor of an Albanian alphabet tradition (Vangjel Meksi… etc. p. 29). Above, we described the pleasure of believers and priests when religious services were conducted in Albanian.

Albanian students in Greek schools certainly experienced the same feelings when they carried the Gospel in Albanian or the books of the French writer Fleury: “Customs of the Israelites” and “Customs of the Christians,” also translated by Vangjel Meksi, “to be used especially in schools” (Albanian Encyclopedic Dictionary, 689).

THE RENAISSANCE BEGINS WITH MEKSI

Until the beginning of the 19th century, all efforts of Albanians to have the full Gospel in their mother tongue had failed. Albanian intellectuals were clear that, in the conditions in which Albania was, only through the Gospel in Albanian, which would be used in churches and schools, could the Albanian language and through it the identity of our nation be kept alive. At the beginning of the 19th century, a suitable ground for the cultivation of the Albanian language had been created in Ioannina.

It is known that Ali Pasha taught Veli, his son, the Albanian language, while he encouraged Albanians and foreigners to cultivate it. In 1814, the Englishman Leake, a friend of Ali, published the first Albanian grammar, compiled together with E. Vithkuqari. A few years earlier, the British Bible Society established a committee that would support, financially and otherwise, the publication of the New Testament in all Balkan languages. In these circumstances, Dr. Vangjel Meksi’s desire for the profession of doctor, which was likely imposed on him, seems to have been extinguished, and a very large fire was ignited, which would push him to serve his nation.

These fires have not infrequently been ignited in the chests of the Meksaj, an indigenous Albanian family, documented in these lands for at least 1000 years. I am inclined to believe that Vangjel Meksi abandoned the profession of doctor, not for reasons related to religion, but to realize an ancient dream of the Albanians, the introduction of the Albanian language in churches and schools.

Ancient, at least, since 1555, when Gjon Buzuku translated and published the Missal. After this important decision, both for him and for the Albanian language and literature, Meksi drafted in detail the project that would lead to the Albanian translation of the Testament.

The realization of this project required, above all, “perseverance, great strength, and experience.” And he, “as a resident of Rrëza, had these qualities in abundance.” (Hahn, “Albanian Studies,” Jena, 1854, p. 265). First, he abandoned his profession, Ali, and Ioannina and moved to Italy, where he continued the study of the Albanian language, which he had begun in Ali’s court, and in 1814, he published Fleury’s books in Venice, translated into Albanian and adapted for Albanian students.

He then returned to the Balkans, where he connected with the representatives of the Bible Society to sign the contract, which paved the way for the publication of the Bible in Albanian. The representative of the Bible Society in Istanbul presented the agreement with Dr. Vangjel Meksi to the Patriarch. He was forced to accept that he would give his full support. However, that same Patriarch ordered the public burning in Elbasan of the Albanian manuscripts of religious texts translated by Dhaskal Todhri.

It is quite understandable that the New Testament in Albanian only saw the light of day thanks to the intervention of the English Bible Society and the personality of Dr. Vangjel Meksi and later Grigor Gjirokastriti. In this way, Vangjel Meksi realized his magnificent project, according to which, starting from 1824, believers heard the word of God in Albanian, while Albanian students in Greek schools also learned with books in their mother tongue.

The introduction of Albanian in churches and schools during the first quarter of the 19th century was a miracle that became a reality only through the Albanian translations of Vangjel Meksi, at a time when there was no alphabet and orthography to write Albanian, nor schools to teach it. Nevertheless, Vangjel Meksi completed the translation of the New Testament. A work that was not realized during all the past centuries, Vangjel Meksi completed successfully in only 15 months, without having the necessary experience and only with a medical degree.

It is likely that Vangjel Meksi did not work alone. He must have been part of an intellectual lobby of distinguished, patriotic Albanians with liberal religious ideas, such as Grigor Gjirokastriti, etc., with whom he shared the same convictions about the church, partly in Albanian, about the role of Albanian in schools, and about the value of the victory of the Greek and Romanian revolutions for the future of Albania.

The path followed by Vangjel Meksi, Grigor Gjirokastriti, Naum Veqilharxhi, and later Kristoforidhi, to introduce Albanian into churches and schools through the Gospels and beyond, was a very well thought-out action. They exploited the educational and religious institutions dependent on the Patriarchate, under the pretext of better assimilation of religious dogma through the mother tongue.

In fact, Albanian historiography has overlooked the work of Vangjel Meksi. Only one line is dedicated to him in the work “History of the Albanian People,” volume I, p. 412, and moreover, he is not taught in schools today. Only a solitary voice has recognized that Vangjel Meksi took an important step in the cultivation of the Albanian literary language and that he is a forerunner of the Renaissance figures in this field (Encyclopedic Dictionary, p. 689).

In fact, there are numerous documents confirming that the Albanian National Renaissance begins with Vangjel Meksi, it begins with his work, which starts 10-15 years before the date officially recognized by our historiography. Vangjel Meksi’s activity, related to the cultivation of our language, extends over the period from 1814 to 1821. During this time, the Albanian translations for schools were published (1814), the grammar (before 1819), and the complete New Testament, with the original alphabet and corresponding orthography, was submitted for printing (1821).

Prof. Dhimitër Shuteriqi wrote: “The history of the New Testament, translated into Albanian by Vangjel Meksi and edited by Grigor Gjirokastriti, influenced Naum Veqilharxhi and Kostandin Kristoforidhi, and triumphed during the National Renaissance, when the struggle for Albanian as the language of literature, school, and religion was an important part of the struggle for liberation” (V. Meksi… etc., p. 9).

Dhimitër Shuteriqi continues in another study: “Vangjel Meksi was the first to undertake work for Albanian schools. It is understandable why he prepared school texts with religious content. Naum Veqilharxhi did the same. (Dh. Shuteriqi, Albanian Writings in the Years 1332-1850. Tirana 1976. p. 174). In the literature texts of secondary schools published in the 1950s, the due space was reserved for the life and activity of Vangjel Meksi.

Apparently, the absurd war against religious beliefs that erupted in the mid-1960s alienated Meksi, (who was mistakenly known only as a translator of religious works), from students, Albanian history, and culture. Vangjel Meksi, a distinguished figure of Albanian culture as well as a translator, linguist, and patriot, must return not only to the literature and history curricula for secondary schools, but also take the place he deserves in the text of the “History of Albania.” Memorie.al