By Sandër Lleshi

Part One

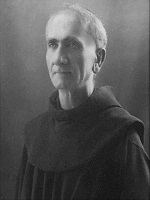

Memorie.al / On the occasion of the birth anniversary of Father Anton Harapi, the well-known historian and military officer, Major General Sandër Lleshi, for the first time gives the public a collection of facts that shed light on the political engagement of Father Anton Harapi in the Regency Council. As a reaction to the famous prayer for Albania by Pope John Paul II, an Albanian Telegraphic Agency (ATA) announcement, dated 10.10.1980, at 09:55 AM, transmitted in English, stated: “In Albania, religion has lost the battle in the ideological and spiritual field once and for all. For this reason, the crocodile tears have been received in a completely different way than the Vatican monarch hoped. If the Popes of Rome continue to defend a cleric condemned by the judgment of our people, because he was an agent or collaborator of the fascist and Nazi occupiers, we would say that this discredits them even more…! Father Anton Harapi and others like him, following the example of Pope Pius XII, who gave his blessing to the Duce and Hitler, put themselves at the service of foreign invaders and they cannot be any different from all collaborators of the occupiers in Albania.”

Thus, even in 1980, decades after leaving him without a grave, the communist dictatorship did not consider the war with Father Anton Harapi closed, even though it claimed to have won the battle against religion in the meantime. But how is this possible?

While studying the history of World War II, a few years ago I came across some very interesting testimonies regarding Albania, and also Father Anton Harapi, in a book written by Hermann Neubacher, titled “Sonderauftrag Südost 1940–1945: Bericht eines fliegenden Diplomaten” (Special Mission Southeast 1940-1945: Report of a Flying Diplomat), published in Göttingen in 1956.

Hermann Neubacher was born in Wels, Upper Austria, on June 24, 1893. With the beginning of the National Socialist movement in Germany in the 1930s, he became politically engaged, playing an important role in the union of Austria with Nazi Germany, after which he immediately became Mayor of Vienna in 1938. In 1943, until the end of the war, his mission expanded to include the competence of Plenipotentiary of the German Foreign Ministry for the Southeast. In 1951, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison in Yugoslavia, from where he was released in 1952 due to a serious illness. From 1954 to 1956, he was entrusted with the mission of advisor for the construction of Ethiopia’s administration. Hermann Neubacher represented the central political figure charged with the political management of Southeast Europe, having been granted full political and diplomatic powers.

His memoirs, which shed light on one of the important fronts of World War II, the front where this war conspicuously displayed its partisan character, are of great significance. Hermann Neubacher’s work represents a first-hand document of importance for all those interested in the history of World War II in the theater of Southeast Europe. An interesting conclusion was given in the English magazine “International Affairs” in 1958, in R.G.D. Laffan’s review of Neubacher’s book:

“This short memoir of value and without many pretensions is an excellent work to read. Dr. Neubacher, the former Mayor of Vienna, was sent to Bucharest in 1941 to ensure that Romanian oil reached Germany. As German problems in the Balkans grew, the sphere of his activity expanded greatly, so that in 1943, he was appointed ‘Plenipotentiary and Special Envoy of the Foreign Ministry for the Southeast,’ and was constantly flying between Belgrade, Athens, Tirana, Cetinje, Berlin, and Hitler’s General Headquarters…”!

Among many engaging passages are those about the Albanians, whom he sometimes refers to as “sympathische Räuber” (sympathetic robbers). And among the evaluations of virtuous people, the most touching is the one about Father Harapi, the martyred provincial of the Franciscans of Shkodra.

He must be a good fellow

Everyone is asked to consider the fact that Neubacher wrote his memoirs without any hope that they would find a way to Albania, which was hermetically sealed by communist totalitarianism. Now let’s turn to Neubacher’s testimony.

ALBANIA IN 1943

Hitler generally had a low sensitivity regarding the strategic role of the Balkans within the framework of World War II and had left it as a sphere of Italian influence. In this perspective, he had silently tolerated the Italian occupation of Albania. In general, the growth of German engagement in the Balkans was in direct proportion to the Italian failures there. Thus, at the moment of Italy’s capitulation, German troops entered Albania to fill the vacuum created in this region of considerable strategic importance, at a time when the possibility of an Anglo-American landing existed-a landing that would sever the connection between German troops deployed in Greece and those stationed in Yugoslavia, under conditions where Bulgaria and Romania were attempting to switch sides to the Allies.

Immediately after the capitulation of Italy in September 1943, Neubacher writes in his book that; “Ribbentrop summoned me in Belgrade and informed me that the Führer wished for ‘an independent Albania, which would emerge from an internal initiative’; the next day, September 11, I had to join the German division in Elbasan. A special aircraft would also bring me an expert on the country and the language, who would accompany me to Albania. I had to march with the division to Tirana and carry out my mission.”

Neubacher describes the course of events in the Balkans, and within this framework in Albania, with enviable precision, not only listing the most important facts but also providing very complete analyses of them. In addition to the events, he dedicates attention to the main characters of his book. As quoted above in the International Affairs review, the assessments of Father Anton Harapi are among the most heartfelt.

Although Neubacher deals with figures of various backgrounds in his book, such as Anton Harapi, Mehdi bej Frashëri, Xhaferr Deva, or Dragoljub (Draža) Mihajlović, etc., his doses of sympathy are not in direct proportion to the readiness of the individuals in question to serve or collaborate with the German authorities. At a time when Neubacher crushes with his pen even those who were recruited as German secret service agents from the ranks of his Balkan and Albanian characters, he finds the highest words of respect to describe the figure of Father Anton Harapi.

On the Patriotic and Human Dimension of Father Harapi

If we were to place Hermann Neubacher’s testimony against the indictment that led to Father Anton Harapi’s execution, we would shudder at the whole drama. Below I bring a fragment from Neubacher’s book:

“Shkodra 1943: heavy air, nocturnal pressure for money, murders in the middle of the street, in small houses, in cafes. In broad daylight! In a small circle of Albanians and Germans. Father Anton Harapi recounts how the night before, three known men of the illegal communist movement had come to him at the monastery to hold a political debate with him. ‘The Communist Party,’ they had said, ‘was not fighting against the church. Communism is in a new phase of development; it fights for national freedom and for a true democracy. What is the head of the Franciscans, Father Antoni, looking for in a Regency Council that cooperates with the fascist occupiers?’ A German state police officer who was present was seized by a hunting fever: ‘How interesting, Father Anton! Would you be able to tell us who those three men were?’ His ascetic face, carved in wood and with a large nose, turned black with agitation: ‘Don’t forget that I am Albanian!’ The three men, although unarmed, were in his residence, so during this visit, they had the right to friendly protection. However, Communism no longer recognizes such values, not even in Albania. After the withdrawal of German troops from Albania, Father Anton was captured in the shelter of a friend’s house, and those three men were likely among the judges or spectators when he was hanged. These are a few examples instead of thousands. They belong here; I strive to unfold an impression of this multifaceted world, which can be as warm as it is cruel.”

Certainly, the passage above is not an ordinary fragment. It cannot be passed over with the indifference of paralytics and with some lazy phrase like; “…. oh how interesting”?! No. This is an extraordinary testimony, coming from an eyewitness, which dramatically clarifies in a few words the role of Father Anton Harapi, both in relation to the Germans and to his partisan opponents, or his future judges.

But how is it possible that Anton Harapi dares so much? How is it possible that in such a dangerous environment, he rises so high? Where does he find this strength? In fact, he gives the answer himself: “Don’t forget that I am Albanian!” he tells the Gestapo officer.

A few years later, when the roles had changed, Father Anton Harapi faced a communist trial whose members could not forgive. Perhaps stemming from the same motive from which Father Anton Harapi had forgiven. He had forgiven because he was Albanian to the core, while those who condemned him did not forgive precisely for the opposite.

Neubacher was quite struck by the fact that Father Anton Harapi is very Albanian; indeed, in some cases, it seems that he is ready to tolerate, at least in communication with foreigners, some Albanian qualities that even contradict Christian doctrine itself.

In his book, Neubacher gives us another interesting detail:

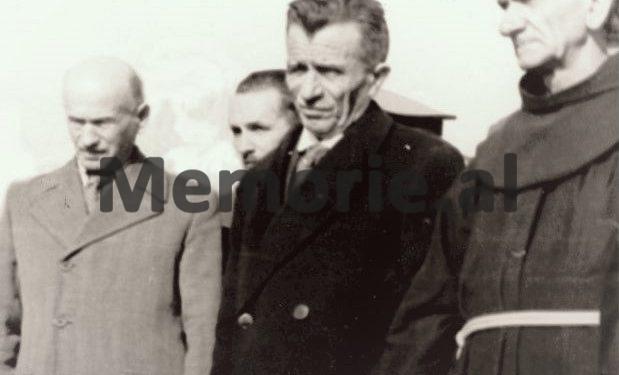

“In my residence in Belgrade, June 1944. Characters: General Glaise-Horstenau ‘The German General in Croatia,’ Father Anton Harapi, the head of the Franciscans of Shkodra, a member of the Regency Council.

Glaise: ‘Tell me, your grace, how do you judge blood feuds?’

Harapi: ‘It must exist, we only have this punishment.’

I intervene: ‘Dear Father Anton has a Mirditor ever confessed to a murder for blood feud?’

‘No, no!’

‘But for a small theft?’

‘Absolutely!’

‘I understand this quite clearly. In a country without a state apparatus, without gendarmes and judges, punishment is exercised by the family or by the community – but I ask you as a moral theologian and as a shepherd of the souls of the Catholic blood feuders of Mirdita, for your opinion!’

‘The principle is just, the application is problematic!’ We will meet again with this majestic monk of prayers. In 1944, he became a martyr of the conscience of his priestly obligation.”

Any Albanian who would be “attacked” with such a complex question by a foreigner would have difficulty escaping the situation uncompromised. Even more so when it comes to a Catholic priest whose mission is to preach love. Father Anton Harapi, although he had accepted a very delicate responsibility as a member of the Regency Council, had refused its chairmanship solely because of the impossibility of signing death sentences, which would have been an obligation of the post of head of state. But in communicating with a foreigner, he does not try to find an alibi in the priest’s cassock, leaving only the Mirditor who sins grievously by taking blood against his own brother. Father Anton Harapi tries to explain this phenomenon that developed as an alternative to freedom and law, in the absence of their own state. / Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue