By Joana Doda & Prof. Asst. Dr. Albert P. Nicholas

The second part

– The persecution of Albanian scientists, in the years 1945-1955; the connection between science and ideology – the case of the persecution of engineer Petraq Qafoku! –

METHODOLOGY

Memorie.al / In the initial part, the analysis will have a philosophical approach, to clarify the connection between ideology and science, according to the model of Marxist philosophy, and on the other hand, a critical approach will be made to this current, based mainly on the work of the philosopher French Zh. Married. The Marxist vision of man and the reduction of the latter to an object will be looked at critically, despite the criticism of Mariten, who defends the human dimension of the person. In this view, we will see how the case of engineer Petraq Qafoku is handled by the communist court and the State Security and how, through violence, his knowledge is used for the “socialist good”.

Continues from the previous issue

So, the regime saw industrialization as a tool for the protection and development of Albanian society, based on the principle of equality. In the first stages, to which our study also refers, this type of communism, according to an “Albanian adapted” form, follows models that do not refer so much to Marxist theory, but mainly to Yugoslav or Soviet models. One of the most violent phases of this process is the introduction of Albania into the campaign of collectivization of agriculture, which creates a real tragedy for the people.

Violence was the irreplaceable tool of collectivization and in the name of “equality”, the private property of individuals and families was systematically violated. In the name of equality, the majority is punished in favor of the “ruling class”, which does nothing but lay the foundations for an inevitable bankruptcy of collectivism itself and the system as a whole. This is how J. Ratzinger defines the failure of development that is based only on technology as such:

“…The development of nation’s degenerates, if human society thinks it can ‘recreate’ itself by trusting in the ‘miracles’ of technology. In the same way, economic development becomes false and harmful if you only trust the ‘miracles’ of finance to support an unnatural and consumerist development”. In this absurd context of the country’s industrial development, the malice that the regime does when it builds the indictment against engineer Petraq Qafoku is introduced: “this engineer does not have the moral premises to make a contribution of ideological value, in the construction of socialism”

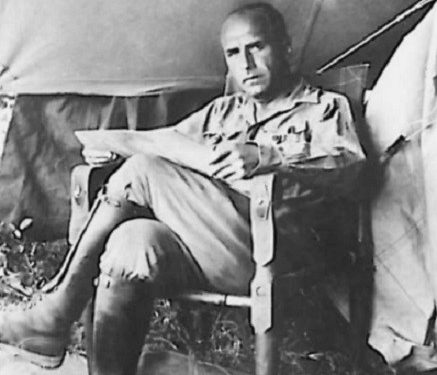

The essence of communist morality requires that every person must demonstrate an unlimited love for the Party and popular power and work selflessly for socialism. Engineer Qafoku claims himself, with a typical sincerity of a high-level intellectual, that he was educated with fascist culture and education, during his studies in Rome. Of course, for a clear and normal mind, this does not automatically mean that he is an agent of fascism. But for a communist investigator, this is the main premise of the investigation.

Here is a part of the dialogue between the investigator and engineer Qafok, which highlights his moral height, where sincerity is his most powerful weapon, which will help him later in reducing the sentence:

Question: As an element and cadre of Italian fascism, what activity did you do and how did you help the Italian Fascist regime?

Answer: “I have not shown any activity for Italian fascism. Although I had a fascist education and culture”.

The dialogues between engineer Qafok and the investigator are a very interesting anthropological source to understand the drama of the accused and the grotesque side of the regime. The insistence of the investigator to highlight the lack of communist morality in engineer Qafoku, forces the latter to start irony with the investigator. Engineer Qafoku has already realized that the punishment is inevitable and uses a biting irony, disarming the investigator, who, with Qafoku’s assertions, feels himself up to the task, as an investigator of the communist regime:

Question: What was your duty as an Albanian, to stay and fight the fascism that occupied the homeland; or to return to Rome, to the schools and to the heart of fascism, as you have returned?

Answer: My duty was to stay in Albania like my friends and participate in the N.Ç.L. Movement, but I did the opposite, I returned to the University of Fascist Rome; my attitude in this case was bad and not good.

Engineer Qafoku admitted that he was not a “new man”, he was not suitable for the communist morality of the new Albania. In addition to the moral side, incompatible with communist morality, the teachings of the dictator Hoxha, put into practice by the investigator in this case, also highlight the fact that engineer Qafoku does not even have the spirit of heroism, which is necessary for the “man of new” communist.

“…The heroic trait is one side of the rich moral image of the young man and cannot be imagined separately from the totality of properties that define his personality”.

From the just-quoted dialogue, the lack of “communist heroism” of engineer Petraq Qafoku stands out. He, being a refined intellectual, is quite clear about the grotesque side of communist heroism and the abuse that the regime does to people, using them as “balloon fodder”, for this reason he chooses to play with irony and accept some truths that may condemn him, but that do not lead him to the death penalty.

The “old man” is not only morally bad and passive. He, according to the mentality of the regime, always acts against the people’s power and sabotages the scientific and technological development of communism. Dictator Enver Hoxha himself gives directives on how to be careful of saboteurs and raises “vigilance”, asserting that; intellectuals are dangerous, while “our young people” are the ones who will build socialism:

“From the first months after the liberation, we had to fight and settle scores with the Italian saboteurs, headed by the former head of the Italian society, and encounter the hostile work of some reactionary Albanian engineers. But as then, when we almost completely lacked tools and cadres, as well as later, when our cadres in terms of knowledge and experience were, so to speak, the students of Soviet saboteur specialists, we did not run out of oil, due to the skill and determination of our people”.

The first point of the indictment begins with the accusation that the defendant Petraq Qafoku, during his studies in Italy, has assimilated the fascist culture and therefore, he has propagated fascism. This accusation is quite serious, throughout the entire time of the dictatorship, but it can be considered especially serious, immediately after the end of the Second World War, when the communist propaganda about the war made such an accusation even more serious, where there was talk of collaboration with fascist enemies. So, engineer Petraq Qafoku was a potential danger to communism and as such should be imprisoned.

The entire dialogue between Qafok and the investigator has a great anthropological weight and highlights a hypothesis raised for years by the philosopher H. Marcuse, who asserted that Soviet Marxism; has become a “science of behavior”. The investigator is persistently looking for every element of engineer Qafok’s “behaviour”. We are in a panorama quite similar to the Soviet one, where the investigation and other means of violence act against intellectuals according to a method of “treating them like children”.

The case of Peyraq Qafok’s imprisonment, sentence and early release from prison is quite interesting to highlight some features of the regime, which faced two strong forces in the exercise of dictatorship: on the one hand, there was the need for violence and terror, which it was the inner call of a dictatorial regime; on the other hand, the regime is aware that it also needs concessions in the interest of power.

The German anthropologist H. Popitz elaborates quite clearly this anthropological feature of the use of violence by dictatorial regimes, in his book “Phänomene der Macht”, where he underlines the fact that the first step in the exercise of power is precisely the use of violence, meanwhile that in a further step, the regime uses instrumentalization: it threatens and at the same time makes concessions as needed, in order to maintain power.

Engineer Qafoku and many other professionals who are indispensable for technical reasons to the regime, due to their professional training, are subject to violence, as they must understand that they are not free and should not have any claim to power. The very nature of professionally trained people makes them dangerous for dictatorial powers, especially when the latter are led by mediocre and, in most cases, ignorant people. Testimonies from family members and relatives of engineer Qafoku, bring us many confessions, how he was threatened with death several times, especially during the investigation period. Anthropologically, the threat of death is the heaviest and most extreme, and through it, the regime demands blind and absolute obedience from the persecuted. The threat of the act of murder plays the role of the anthropological symbol of the regime’s absolute victory over the shocked persecuted.

The indictment continues with the hypothesis of cooperation with foreign engineers who were in Albania, due to the working conditions for the recovery of the economy destroyed by the war and due to the legacy of a pronounced backwardness, compared to the European economies of that time. So, the “foreign enemies” are joined by the “internal enemy”, the saboteur engineer Qafoku who:

“He had connections with reactionary elements, political fugitives abroad; in Italy they gave him letters and links to reactionary elements of our country. It was related to Ing. Taraskonin (Italian) and with Prof. Zuber Stanislav, who was encouraged by them and brought obstacles and disturbances to the work of the Kučova construction site. He had full knowledge of the agent-sabotage organization (Technical-Intellectual), where he consulted with Ing. Stanislav Zyber and Ing. Riza Alizoti. He held meetings of a political nature, with various opposing elements working in this mine and sabotaged the production of the Selenica site.

In the construction site of Kuçova, despite all his extraordinary professional dedication, he encounters great difficulties during his work, from elements of the State Security who follow him and then, during court hearings, accuse him of collaboration with the so-called “enemies of saboteurs”, like; engineer Zuber Stanislav and engineer Riza Alizoti. In the face of these accusations, engineer Qafoku proves an unparalleled wisdom and calmness. Although he is aware that these accusations are false, he knows very well that for such accusations, the death penalty awaits him.

Neither the torture nor the terrible psychological pressure does not break him to affirm false testimonies. Faced with the accusation that he participated in Kuçova’s enemy group, he answers:

Answer: “It is not true that I, Eng. Petraqi, I received instructions from prof. Zuber Stanislava and Eng. Riza Alizoti, I have organized opposing circles, held meetings of a political nature against the People’s Power and sabotaged the work (production) at the Selenica construction site, but I worked as much as I could, for the benefit of the People’s Power, until the day of my arrest on September 18, 1947.

Despite the diabolical passion of the prosecutors and judges and the absurd sentence of 10 years in prison, unsupported by evidence, the regime needs the unparalleled technical knowledge of engineer Qafoku. It is the moment of the instrumentalizing anthropological stance of the communist government. In addition to violence, the government also uses other means, related to temporary and limited freedom for Albanian scientists. The regime uses the same strategy with engineer Qafoku. After being sentenced to 10 years in prison and with Qafoku’s continuous denial of the charges, another court session was organized in December 1948, where the convict was declared innocent.

But the adventures of persecution do not end with this act of innocence. He is constantly under surveillance while working in construction sites and the attitude of the party cadres towards him is extremely distrustful. His conviction, even though he was later found innocent, was like a “biographical stain”, indelible. The ordeal of his sufferings, unfortunately, also followed his family, his wife and two sons. Throughout the time of the communist regime, they were monitored by the State Security and they often had problems with the right to study for higher education, even though about 30 years had already passed since they were acquitted.

An important element that expresses the continuous presence of violence against engineer Qafoku, is the exercise of insult by the regime, during the time when he was not in prison. This study also brings the numerous testimonies of Qafok’s family members, where they remember numerous cases of insults in front of the team, or the awarding of the medal as “Distinguished Worker” to engineer Qafok. Although there was also the “Distinguished Engineer” medal, he was treated as a construction worker and not as an engineer. Emblematic remains, during my study, a testimony of a contemporary of engineer Qafok: “He was extraordinary. A man with high authority, in front of authoritarian people”!

In this perspective, to understand this evidence, the explanation of the philosopher H. Arendt is perfect. In her study; In ‘What is Authority’, she explains the difference between protesta and auctoritas. Precisely in this difference lies the fact that someone (engineer Qafoku in our case) may not have power, but his high moral dimension gives him authority, which is missing in the regime, although he seeks authority at all costs.

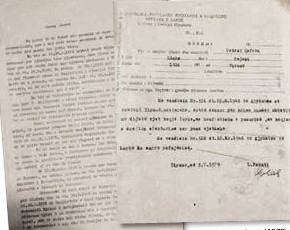

In 1978, when his son Lluka Qafoku wanted to prepare the file for employment, the next incredible event happened: engineer Qafoku still appears in the court records as a convicted person. This fact proves the hypocrisy of the state and the courts, regarding the punishment and the non-respect of the procedures of the registration of innocence, since the interest of the regime at that time was only his release, in order to be used in the construction site of Selenica and not the respect of the right of him as a person. Faced with this situation as absurd as it is offensive, engineer Qafoku decides to address the dictator Hoxha directly, as he sees it as the only way that can provide a solution to the endless ordeal.

The letter to the dictator has a special anthropological value and reminds me of the letter of the Italian philosopher, N. Bobbio, to Mussolini in 1935, about an arrest made by the fascist political police against the philosopher. When the intellectual loses hope in the face of the violent and multifaceted machine of the regime, he looks for the only hope, to go directly to the dictator, because in this case, at least, you are dealing with a person and not a violent and deaf crowd, facing the voice of the innocent.

“Comrade Enver. I ask you to forgive me for taking the courage to address you personally, but I do this because the problem I raise is very important for my work and life. My son on dt. 28.3.1978, requested from the Supreme Court, a document about my judicial status, knowing that I have received the innocence, for a sentence given by the Military Court of Tirana, at my direction. …A document was issued to him, proving that I was still listed in the High Court’s Judicial Status Register, as a convict…! I was forced to write you this letter, because I and my children would carry for the rest of my life without the right, the stain of a traitor”.

The letter expresses the whole drama of engineer Qafoku, about the consequences that the stain of the innocent convict has had over the years, but also the pain for the children’s future. Passing on the consequences of parents’ punishment to children has been a distinctive feature of the Albanian communist regime, and this case highlights it quite clearly.

The letter has an anthropological significance in the presentation of the tribal character of Albanian communism. The Albanian government is formally organized in a bureaucratic form, but however the head of the country, the dictator, is above the law; as such he can provide solutions to problems by exceeding the law, whether it is right or wrong. This is also where Qafok’s cultural sense of smell can be seen, to address the dictator. This tribal element of Albanian communism has caused many clan clashes within the Labor Party, causing numerous victims. The pretext of this violence between clans has always been ideological, but the real motives have to do with the tribal nature of Albanian communism.

In fact, the dictator’s answer comes not directly, but through the court’s obligation to provide proof of the corrected penalty. This happens one year after the letter was sent, exactly, on July 3, 1979. A very important line is added to the previous evidence of the penalty: “With decision no. 328, dt. 10.12.1948, of the Supreme Court, he was acquitted”!

Thanks to this sentence at the end of the penalty testimony, the children of engineer Qafoku, Lluka and Niko, were able to continue their higher studies, recognizing extraordinary scientific achievements: Lluka working in the IT Network of the Academy of Sciences in Tirana and Nikoja, achieving the world’s top leaders in the earth sciences, as part of the US Federal Soil Survey Agency’s Science Board.

CONCLUSIONS

In the communist regimes in general and the Albanian one in particular, since the latter follows the model of the Soviet Union precisely, in the first phase of the construction of socialism, science and industry are given extraordinary importance for the development of socialism, as science and industry ensure the future not only economically, but, according to the communist perspective, also moral. This fact constitutes the essential motive for the persecution of Albanian scientists during communism.

In Albania, unfortunately, as the merciless intervention of the mass mediocrity of the working masses was allowed, in the necessary hierarchy of decisions in the field of justice and social and spiritual knowledge, so was the interpretation of the technical-scientific revolution, as the property of the working class and the working masses, that is: in practice only the practical ideas, necessarily undeveloped and mediocre, primitive, issued by uneducated people, and not allowing the formation of scientific and technological elites, as they were morally unprepared for building communism and could sabotage it.

This would lead to the de facto disallowance of scientific group work, which actually constitutes a ‘sine qua non’ condition for a true scientific research. Thus, in fact, the head was cut off from the real scientific and technological development of the country and the institutions that represented it, because these had to be controlled, both at the level of the personnel they chose, as well as from the topics of research by completely incompetent structures and people, to give opinion in relevant areas. This led, in fact, to the sabotage of real scientific development in the country. Something that did not happen to this extent, in other communist countries, where the inhibiting effect of ideologizing society was limited by the state with the creation of protected structures for scientists and technologists, which allowed them interesting and sometimes successful developments, in the fields where the state had an interest.

In addition to these facts, the use of violence as an anthropological phenomenon occupies a specific important weight in the interpretation of the persecution of scientists. I think that the violence exercised during the regime can be classified as a “general social fact” (concept of the French anthropologist M. Mauss), since it had an impact on every sector of life during communism and had a great impact on those who they have suffered violence and then become victims of a violent mindset. An example of this assumption is the verbal violence of politicians in the post-communist period.

In this political-ideological dispute, the example of engineer Qafoku’s exceptional resistance is not only a very interesting case study, to shed light on that gloomy time, but especially represents a guiding example of maintaining moral and human integrity, in the face of one of the cruelest dictatorships of the 20th century. Memorie.al