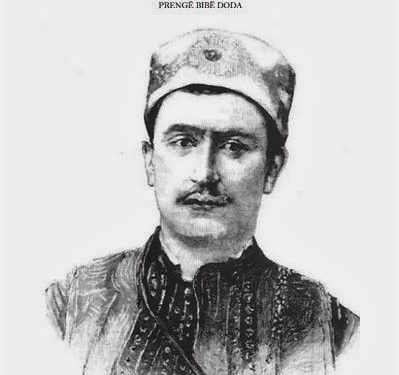

“PRENGA BIBE DODA, THE SHADOWS OF A CITIZENSHIP”

NICHOLAS LOKA

THE MONOGRAPH “ABOUT BIBË DODA, A PHENOMENON IN ALBANIAN POLITICAL LIFE”, A VALUABLE SCIENTIFIC STUDY THAT ENRICHS THE FUND OF OUR HISTORICAL STUDIES

From Mr. Sc. Murat Ajvazi, March 2017, Switzerland

The first part

Memorie.al / The newest book “Prengë Bibë Doda, a phenomenon in Albanian political life”, by researcher Nikollë Loka, not only expands the field of historical studies on Mirdita, the Door of Gjonmarkaj and the shrine of the Mirdita Prince, Prengë Bibë Doda, but it is also a contribution to national historiography. The very rich archival material, the literature used or consulted, oral traditions, etc., make this book a real study treasure, giving the science of history a scientific monograph that enriches our knowledge of Mirdita, its captains, tradition, history etc. Studying such an important and complex figure, such as the figure of Prengë Biba Doda, is a high scientific responsibility that not everyone undertakes. Nikollë Loka, has done a great job of research and treatment by the professional researcher, giving us the portrait of the Prince and the general Mirditor, with the true contours. Loka has adhered to the end of space and time, in which the multidimensional events and their protagonists have unfolded.

Mirdita, in the entire Albanian space, is known as an unsubdued province, which has continuously revived the early national tradition, has persistently preserved the pre-Turkish faith and, what is very important, the Code of Leka. With all this, I think this province has played the role of the generator of the Albanian being in general. The author Loka, in order to make the figure of Prenga of Gjonmarkaj clearer, has brought numerous documentary data and popular memory about Mirdita as a whole and about the door of Kapidans such as: Marka Kolë Gjoka, Gjon Marku, Preng Lleshi, Dodë Prenga, Prince of Kapidan Bibë Dodë Pasha, to the protagonist of this monograph, Prince Prengë Pasha.

Loka has managed to successfully reflect the contribution of the Gjonmarkai of Mirdita, in the successes of the Bushata Pashallars, for the subjugation of Montenegro, as well as the help to Ali Pasha Tepelena; the contribution to the defense of Albanian lands and the fight for the independence of Albania, in support of Prince Widi, etc. In this monograph, it appears that Prince Prengë, more than his predecessors, assumes the role of leader of the National Movement and has a clearer vision for the future Albanian state. Kapidan Prenga took over the merger of the regional autonomy within the new Albanian state, an important fact that shows high political maturity.

It is known that Prengë Bibë Doda, was a politician raised in the eastern environment and formed with western culture, in an American school, the best that the Ottoman Empire had at the time. Important politicians and diplomats, local and foreign, have appreciated him as a personality with indisputable influence, high culture and special prudence. The fact that he wore the high decorations such as: “Great Cord of Mejidia” and “Commander of Osmania”, from the Ottoman Empire; “Grand Cordon of the Order of the Crown of Italy”, from the King of Italy, as well as the sultanate rank; “Mirymerallek”, equal to that of the Brigadier General, clearly shows what importance it had.

In the light of the documents, the author has also elaborated on the qualities of manhood, justice and pride of Prenga Biba Doda, these virtues, which elevate his example.

However, this book, although it focuses on Prengë Bibë Doda, is also a genuine genealogy of Gjonmarkaj and a summary, three-century history of Mirdita, in her efforts for survival.

Researcher Nikollë Loka deserves congratulations for this scientific achievement. In the entirety of the book, he has never allowed himself to violate the historical truths, managing to give us the life of one of the most important Albanian politicians of the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, in extremely difficult situations complex that our country went through. In my opinion, this book is an example of how historical figures and events should be treated.

PRENGE BIBÉ DODA, A PHENOMENON IN ALBANIAN POLITICAL LIFE

Attempts to illuminate the path of Mirdita in history have been numerous and have their beginnings since the period of the National Renaissance. The history of Mirdita, being inextricably linked with the Door of Gjonmarkaj, has been obscured and anathematized, without being subjected to an objective assessment. Meanwhile, in the period of democratic developments, Mirdita and Gjonmarkaj were written in black or white, depending on the viewpoints of the authors. These positions in rigid positions have hardened the broad view of the events that have happened in relation to this province. From these positions, you can also see the figure of Prengë Bibë Doda, one of the most prominent Albanian personalities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Like Gjonmarkaj, Prenga was the worthy successor of the line of the chief Kapidans, who did everything to preserve the function of the Head of Mirdita. Gjonmarkaj led the warlike Mirdita, who was looking for his head at the front of the war. Not a few of them had given their lives during the wars, conveying the glory to their Door. And Mirdita, having such fighting men at her head, did not stop before any danger, through the many battlefields. Gjonmarkaj gained power at a certain moment in history, as it happens in all cases, but they have the great merit of staying so long in the rule of a proud Province, which would not accept you, unless they answer her pride. As the leading Door bound in agreement with the High Gate, the Gjonmarkaj chiefs were obliged to respect the agreement made with the Ottoman authorities. This task was difficult, since the Mirditas, as free people, were inclined not to recognize foreign law, foreign officials and foreign authority. In Mirdita, power was not exercised in the name of the Sultan and the kaymekams were not changed according to the mood of the next Vali. In those places, the Kanun had decided who would govern.

He had decided only once for all time, therefore the Assembly of Mirdita, was not involved in the fever of power and, when he felt such fever, the leaders who defended “constitutionality” objected, because in those mountains, it was obligatory for every person to know his turn of the country and the assembly. Moreover, in Mirdita, administrative orders were not enforced, there was no gendarmerie and no army, and there all people were legally equal. Wise men would gather and give a solution, and if that solution did not please the parties, it was judged higher up, up to the Door of Gjomark, as the last instance of the interpretation of the Canon.

Meanwhile, the Ottomans wanted to integrate this province into their system of government. The very essence of Mirdita’s autonomy makes the Gate of Gjonmark an intermediary between the Mirditas and the authorities, therefore it is to the credit of this family that it was able to guarantee this agreement and maintain a state of relative peace between Mirdita and the High Gate. Other provinces, such as the famous Suli, which did not find a common language with the authorities, went to extinction.

The Mirditë-Gjonamarkaj agreement was long-term. The Province would respect the authority of the Chiefs under any circumstances, but even the Gjonmarks were obliged to keep the autonomy of the Province sacred, regardless of the sacrifices required.

Prengë Bibë Doda was influenced by this story of Gjonmarkaj and especially by the heroic life of his father. With his feats, iron character and a hero’s life, Bibë Doda has left a mark on his son.

It is said that at the time of that strict warrior, three Pashalars lived in Shkodër: two Muslims and one Christian. It was not like that anywhere, because there were no Christian Pasha. Well, Bibi Doda was the first exception. As a Christian Pasha, Biba was greatly appreciated and respected by the Christians of Shkodra, Malësia, Puka and Zadrima.

The branch of Biba Doda of Gjonmarkaj lived in two places at once: in Shkodër and Orosh. Each center helped the other; Oroshi is the place of resistance, while Shkodra is the place of politics and diplomacy. In that environment, next to his father, Prenga was born and spent the first years of his life. Although they lived in Shkodër, the capital of the Vilayet, in the Palace of Bibë Doda, the names, surnames, language and customs were pure arboreal.

It was a ray of light in the gloom of Shkodra that had lost its former glow in the long Ottoman night. Freedom lived in the palaces of Kreu today, conditional as it was two hundred years ago in the form of traditional self-government, or unconditional, as freedom that comes from human sacrifices in the struggle for self-government. If the Turks wanted Mirdita as an ally, they had to accept it as it was, while if they worked with a traitor, then the Mirditas would go out to the mountains with rifles in hand.

The people of Mirdita demanded very little from the authorities: to live like an Arab and to be governed by one of the Gjonmarkaj. In exchange, they gave the Sultan, several thousand soldiers who poured into the battlefields with their fiamur, dressed in their national clothes. This was the freedom that was not violated in the mountains of Mirdita for five hundred years. This freedom surprisingly depended heavily on one man. It had happened like this in two generations: Bibë Doda had remained the only son of Dodë Prenga, after his brother had been killed, and Prenga was the only son of Bibë Doda. The Turks had once been enthused by the glory of Mirdita’s armies and had appreciated Captain Biba, but from that height, he had begun to worry them. However, for the rest of his life, no one dared to shake his throne. Everything was prepared to happen after his death.

Bibi Doda was poisoned and died, while her son was taken to Istanbul, supposedly to protect him from the dangers that threatened him and to educate him. Mirdita was thus orphaned, without its traditional leader, although in Orosh, the family of the Kapidans lived, who were honored as Captains, but none of them had the right to tend to the Krahina, as long as the natural Head, Prengë Biba Doda , was alive. The province, according to the Canon, had always honored the Kapidans and in the Canon Law, the obligations of the people, or the chiefs, towards the Gjonmarkai were clearly defined. But Gjonmarkaj also had obligations not only to the people of the chiefs, but also to the first of their Dera, who was the first son, of the first brother. Mirdita’s Treva remained strongly connected with Biba Doda’s son. As a result of this connection, never broken, she kept the throne of the Head of the Province, for 37 consecutive years and no one sat in his place, neither from the Kapidans nor from the Turkish Kaymekams. Preng Biba Doda, was a contradictory figure.

Rarely is there another personality that holds so many ambiguities within itself. Prince and Pasha, Mirditas who did not live in Mirdita, man of the assembly and diplomatic salons, with light and shade as a patriot, prudent in words, but much more prudent in actions.

In order not to be mistaken, Prenga retreated from the developments, trying to find the right moment, to think about his position. He sacrificed a lot in his life and as long as he lived, he reaped benefits from his sacrifice. He was learned and smart, in a country where most people were illiterate and what is more important, he could not be trampled by anyone. Prenga’s life is a labyrinth with many zigzags. For a complex person, a simplified black and white assessment never gives the true dimension of his personality. He was next to the Sultan and in the diplomatic salons of the Great Powers, an exile and a man with high functions in the state, he was therefore simply a precious hostage, to whom the Sultan could be given everything, but he was reluctant to allow him to return to his homeland and known as the Head of Mirdita.

Prengë Bibë Doda, he could have left his hometown and in exchange for this, he would receive even higher ranks and more important functions in Istanbul. He had reached the rank of General and commanded one of the two Albanian brigades, out of the three brigades in the Ottoman Imperial Guard. But he wanted neither position nor benefits, because he did not have complete freedom to choose. It is known that the high functions in the Sultan’s Court were more important than the function of the Head of Mirdita, who somehow depended on Valiu in Shkodër, but he was born to remain the Captain of autonomous Mirdita, as a guarantor of the country’s autonomy own. Handcuffed, he did not dare to exchange Mirdita’s freedom and had no way to erase the memory of his family. He could not be alienated, as the cost his family would pay in this case would be high. It had not happened that any of the Gjonmarks before him surrendered their self-government.

Was Prenga eternally connected to Mirdita under any circumstances? The facts showed that; he planned to surrender the autonomy of Mirdita, as soon as the independent Albanian state was formed. Prenga wanted to take over the historical role of integrating Mirdita into the Albanian state structures, a mission that was interrupted with his death and produced long-term consequences for the Province. For Mirdita, Prengë Bibi Doda sacrificed everything that was asked of her. Eighteen years old, fought against the Turks; twenty years old, against the Montenegrins; spent 37 years of his life in exile; they made him incapable of leaving descendants. They could even kill him! What else could they do to him!?

Prengë Bibë Doda was a politician who turned disadvantages into advantages. Thus, he compensated for the lack of familiarity with people, which came from long exile, with the luxury of observing events from afar, never getting involved in their whirlwind. While the lack of desire, to deal with small things, made him stay away from them, leaving Marka Gjon as his deputy in Mirdita, who had the task of solving problems in the Province, while Prenga himself dealt with the consuls and authorities in Shkodër, or led the work of the government in Vlorë and Durrës.

As a politician, Prenga was prone to dialogue and did not prefer to impose himself even when his interests were harmed, choosing the lesser of the evils. He had to, for a time, reconcile two opposing positions: the Ottoman efforts to weaken the autonomy of Mirdita and the efforts of the Mirditas to preserve and strengthen the autonomy. When he didn’t like any decision of the authorities, he put the will of the people in front of him. And when the leaders of the day did not like any decision of the authorities, but he had consented to it, he put his will in the middle, even threatening to resign. Everyone knew what Prengë Bibë Doda had done for Mirdita, that’s why no one dared to take his word back.

The Prince and Pasha named Prengë, was used all his life to serve, but never to be used by anyone. In difficult moments, he made very important decisions, independently. He used to consult with foreign diplomats often, but sometimes, he acted against their will. In the same way, he knew how to express objections to the positions of high Ottoman officials and sometimes neglected the Vali of Shkodra, as if to show him that in those areas, he too had to be questioned. So, in every case, he tried to create the impression that he was indispensable.

Regarding Biba Doda, he had several other advantages, which he knew how to use. These were his family background, culture and upbringing, the knowledge he had and his optimistic way of looking at things.

Yes, was Prenga at peace with himself? In many cases, probably not. The fluctuations and big turns he took prove that he saw his attitude critically and tried to become more acceptable. It seems that he had an intention, that after the declaration of the country’s independence, he would start a new political life, with completely different visions, hoping that he would remain useful for the country.

Prengë Bibë Doda had not yet said the last word. His mission remained unfinished.

As a personality of Catholic origin, Turkish education, and Western and Eastern culture at the same time, he saw himself as a unifying nationwide figure. Prenga was a patriot. But his patriotism started with Mirdita and for a long time, ended with that province. Later he loved the Motherland completely. Perhaps he died because he had begun to love her sincerely. By doing so, Prince Prengë Bibi Doda (Pasha) lived in its own time and remained there, a victim of a lowly trap of the politics of the day.

By Nikola Loka

MIRDITA IN WORDS AND DOCUMENTS

-Mirdita in word of mouth-

Rumors about the origin of the Mirditas are numerous and sometimes contradictory, but in general, they coincide. According to tradition, the connection between Shala, Shosh and Mirdita is shown in different ways, but all of them coincide between them and basically show the same thing: the connection of these provinces to each other. It is said that; Mirdita with Shalë and Shosh, with whom they were related, came to today’s lands, from the parts of Kosovo, and first settled in Zogaj, near Shiroka, by the Shkodra Lake. From there they separated and each took their place, where they are today. Another tradition derives from Dukagjini. “They say that they have three brothers in Dukagjin and before I was separated from the fire, they wanted to share the property they had: a horse saddle and a sack. The saddle was taken by the eldest of that place, where he put his back, the name of the saddle was given to him; the second, he met Shosha, and that place where he turned his back, he was named Shosh; the third didn’t know what to do with me, and said to the first two brothers: “Here you go, let me have a good day, because I’m going too, find me some place for myself”1.

Regardless of the fact that it is about the brotherhood, there must have been “three tribes, brothers of Mdhaja to some extent, who came to Shala, Shosh and Mirdita 2.

Father Benardin Palaj, thinks that; “First of all, Mirdita came and took a seat in Orosh. After a few years, the ancestors of Shoshi also flocked: (Gjol and Pepe Suma, the nephews of Mark Dita, took a place on the hill of Saint Qurku, where they found Karmasor and Drogobat, who were flocking with war and took their place. the late Shala, 80 years after Shoshi” 3.

The oral tradition about the arrival of the Mirditas in today’s lands is also related to Hasi. It is said that three brothers, from the side of Gjakova, from Pashtriku, came and settled: in Orosh, Spaç and Kuzhnen. From here, the tribal bajraks that form the core of today’s Mirdita 4 were formed.

Dom Nikollë Kimza wrote that: “Mirdita, born from the bajraks Orosh, Spaç, Kuzhnen, is said to be descended from the Marin (or Morin) tribe. These three bajraks are always called the bajraks of the tribe. The three bajraks of the tribe, because they come from the same tribe, they call each other brother.

This brotherhood, they have neither social brotherhood, nor political brotherhood, nor against the Mohammedans, but in the diftition of one source and one source, the brotherhood that flows from one blood. These brothers, they say that they also have it with Shala and Shosh. From this brotherhood that Oroshi, Spaçi and Kuzhneni claim to have, none of the three have taken or given wives, until now they say: “Brother, friend, there is no way to do it”! Religious discipline has never stopped them, nor does it stop them now, because they have removed too much blood of brotherhood, which they have so that they do not marry each other, but they are never responsible nor do they respond” 5. Memorie .al

- AQSH, P.586, D.41, year 1928, p. 96

- Kolë Shtjefni, Ethnic Mirdita, Monograph, no publishing house, Tirana 1997, p. 12.

- Prelë Milani, Shoshi, Geography, genealogy, history, “Albin” publishing house, Tirana, 2011, p. 243

- Mark Tirta, Migratory movements of Albanians, Academy of Sciences of Albania, Tirana 2013, p.174

- Nikolle Kimza, On the age of Dera Gjomarku, Kumona e e Djella”, No. 12, year 1939 p. 184

The next issue follows