By Dr. Nikol Loka

Part eleven

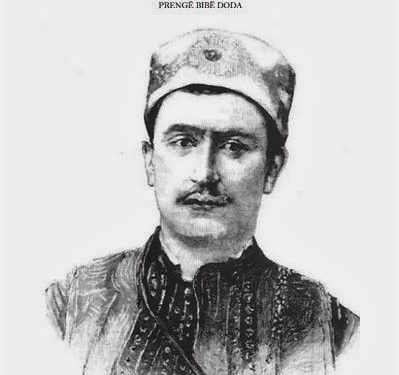

“PRENGA BIBE DODA, THE SHADOWS OF A CITIZENSHIP”

Memorie.al / The newest book “Prengë Bibë Doda, a phenomenon in Albanian political life”, by researcher Nikollë Loka, not only expands the scope of historical studies on Mirdita, the Door of Gjonmarkaj and the figure of the Mirdita Prince, Prengë Bibë Doda, but it is also a contribution to national historiography. The very rich archival material, the literature used or consulted, oral traditions, etc., make this book a real study treasure, giving the science of history a scientific monograph that enriches our knowledge of Mirdita, its captains, tradition, history etc. To study such an important and complex figure, as the figure of Prengë Biba Doda, is a high scientific responsibility that not everyone undertakes. Nikollë Loka, has done a great job of research and treatment by the professional researcher, giving us the portrait of the prince and the general Mirditor, with the true contours. Dr. Loka has adhered to the end of the space and time, in which the multidimensional events and their protagonists have developed.

THE MONOGRAPH “ABOUT BIBË DODA, A PHENOMENON IN ALBANIAN POLITICAL LIFE”, A VALUABLE SCIENTIFIC STUDY THAT ENRICHS THE FUND OF OUR HISTORICAL STUDIES

(By Mr. Sc. Murat Ajvazi, March 2017, Switzerland)

Prengë Kola, Captain of Oroshi, wrote to Prengë’s mother: “I agree with the set price of three thousand Napoleons, for the sale of materials from the forest of Qafë-Molë” (201).

As it seems, the forest was owned by all Gjomarkaj and from its sale, everyone would benefit, according to the area they had.

In order to cope with the many expenses, which came from the countless visits of state officials, foreign diplomats, various leaders and even ordinary people who wanted to meet him, Prenga spent a lot, that’s why he always needed money. It has been subsidized, almost regularly, by France, Austria-Hungary and Italy. In separate periods, he has received salary and bonuses from Turkey.

Despite the amount of money he received, he did not have what he needed, so he asked for financial help. In relation to this behavior of the prince, in an Austro-Hungarian diplomatic report, cynically, it is written: “Hardly any other Pasha in Albania is better suited to the title than Preng Bib Doda, who has made his own motto, that; “without money, there is no love for the Motherland”. (202)

Officially, Kapidani supported the Austro-Hungarians in their battle against the Serbs and Montenegrins. Ballhausplatz, gave him an annual pension of 24 thousand kroner. (203) Likewise, Italy gave him an amount of 50 thousand francs a year. (204) The financial aid was conditional and used to pressure the politician to defend the political line of the donor states. This protection was not always done by Prenga and therefore sometimes his subsidies were interrupted, only to be restarted in another situation.

Prenga tried to take advantage of Serbia and Montenegro, but Belgrade and Cetina knew that; “He didn’t keep his word, that’s why they didn’t subsidize him. With the interruption of subsidies, Mother Marjela and Sister Dava have also benefited. In Prenga’s absence, they managed the family’s economic activity. In a document found in the Fund; “Prengë Bibë Doda”, it turns out that; “Emrullah Bey Dizdari and his brother took 30 Napoleons from Dava, the daughter of Kapidan Pasha. There is no date”! (205)

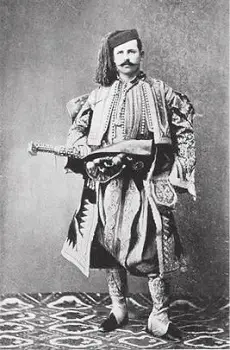

French coronation, in the name of Emperor Napoleon III

When the boy turned seven years old, Bibë Doda, thought that the Emperor of France, Napoleon III, would give him the baptism. The captain presented that wish to the Consul of France in Shkodër, who, through the mediation of the Foreign Minister, informed Napoleon III. The Emperor of France gladly accepted to become the godmother of Prenga and Biba Doda, made preparations to go to Paris, with Margjela, the daughter and the son, accompanied by 6 small boys from the day, dressed in national clothes. (206)

After the poisoning of Biba Doda, it was considered impossible for Napoleon III to keep Prenga in the coronation and appointed the Consul of France in Shkodra instead.

Since the Consul performed the consecration in the name of the Emperor, Prenga was recognized as a parishioner of Napoleon III, who had sent him several gifts for that marked day, including a small gold sword, which Prenga compress on that occasion. (207)

Meanwhile, the French government gave him an annual pension of 5,000 francs. The only son of Biba Doda, although an orphan, had the protection of the Mirdita highlanders and the French state. Therefore, the High Gate made good calculations to remove him from the country, finding an acceptable pretext. If they left him in Albania, the Turks could not eliminate him from power. By removing him, many opportunities were created, which the Turks did not hesitate to try, although without result.

Prengë Bibë Doda, was held in exile in Istanbul, under the pretext that he was continuing his schooling. (208) The Turks tried with soft measures to put an end to the mission of the Doda family. Prenga continued his studies in the same school where the Sultan’s sons also studied. (209)

At the end of his schooling, Prenga was fluent in three foreign languages: French, Italian and Turkish. This chosen education was a great luxury in the conditions of Albania at the time, which was almost illiterate, and made Biba Doda’s son capable of taking on an important role in future developments. Of course, the Ottoman authorities would like the young Prenga to become an Ottoman administrator and then he would not lack great privileges. His and his family’s life would be peaceful and trouble-free, but Prenga could not withdraw and could not compromise with the canonical function he had inherited.

The first internment

Biba Doda’s ten-year-old son was taken by the authorities and sent to Istanbul, allegedly for studies and security reasons. It was a well-known practice to take prominent sons, to remove them from their social environment and raise them with loyalty to the Sultan. In the correspondence between Princess Elena Gjika and the Arber revivalist Jeronim De Rada, Elena Gjika often mentions the Doda family and, among other things, gives information about Prenga’s childhood.

Elena, who was in contact with Albanian intellectuals in exile, knew about the fate of Biba Doda’s family. She writes to De Rada: “To compensate the great services of the Prince of Mirdita, where the soldiers had fought like heroes in Silistria, they have sent his old mother and son to Istanbul as prisoners. The son of Bib Doda, Prince of Mirdita, is always imprisoned in Constantinople, where his grandmother, exiled with him, has died. Partitions punish Albanians, making them powerless, regardless of their abilities. (210)

This internment did not mean inhumane treatment, or ill-treatment although they were used. It was only intended that a potential adversary be broken “for the better”, proving on himself the “care” of the government and the Sultan. Usually, the children who were sent to such “internment” were alienated, changed their religion and identity, forgot their parents and were educated in the spirit of Ottoman patriotism. This practice, in the case of Prenga, failed because he had formed the consciousness of his origin. He had learned many things about his father’s death, perhaps also about the Turkish plans, about sending him to Istanbul.

That merciful attitude of the authorities would have been understood as aristocratic behavior, if the sterilization did not happen, so that he could not leave offspring. So, we have a combination of gentle methods, to keep him away with barbaric methods, to make him harmless and worthless to his cause. At that time, such miracles happened in the Ottoman Court: on the one hand, they educated, gave high titles and decorations, even gave them positions, however, they treated them as potential enemies, who had to be disarmed, to become harmless.

In the case of Prenga, it was intended that he, from a symbol of traditional autonomy, turn into a symbol of integration, into power structures. If the Chief of Mirdita would accept government functions, then the other chiefs, under his example, would do the same and the traditional autonomy of Mirdita would, without feeling it, come to an end.

Was Prenga satisfied with the treatment given to him by the authorities? Taking Prenga’s behavior as a whole, after returning from the first exile, it turns out that; the son of Biba Doda, did not harbor a hostile attitude and agreed to cooperate with the authorities, with the only condition that they respect Mirdita’s autonomy. Despite the great distrust they showed, Prenga initially followed the path of compromise. Prengë Pasha was not a born opponent of the Turks, nor their sworn enemy, but he was a sworn defender of the autonomy of the province he presided over.

Even the Turkish officials were not personal enemies of Biba Doda’s son, but opponents of Mirdita’s autonomy. This misunderstanding had taken him to Istanbul and left his mother and sister far away. As a hostage to Biba Doda, he left Mirdita for 8 years, in an ungovernable state, when chaos, confusion and chaos reigned everywhere. But during all these years, the voice of the Mirdita leaders did not cease, who did not stop asking for the return of Biba Doda’s son to the homeland and promised that, with his placement in the Head, everything would be fixed.

The Mirditas were real enemies of the Ottoman state and posed a permanent danger, because they could join forces with the enemies of the Ottoman Empire as soon as the opportunity arose. In order to get ahead of the evil, the High Gate sought to remove the autonomy of the province. This process had been unsuccessful during Biba Doda’s lifetime. But with his death, the opportunity seemed to come. The removal of autonomy did not depend entirely on the Ottoman authorities, because it was deeply rooted in the belief of each mirditas, their essential value. They had no intention of compromising the freedom for which they had sacrificed so much.

Therefore, the disagreements, between the High Gate and Mirdita, continued for a long time and the Mirditas often went into disobedience and, when they found the opportunity, they persistently demanded the placement of Prengë Biba Doda as their Captain. (211)

On March 26, 1876, they sent a delegation to Shkodër and informed the High Gate of the determination of the people of Mirdita, in their repeated request, for the return to the Motherland of Prenga Bibi Doda and his appointment as Kajmekam. But even this time, Valiu opposed the requests, on the pretext that Prenga was continuing his studies. In response, the Mirdites refused to accept two kaymekama, appointed by the Vali of Shkodra. (212)

Then they asked for Biba Dodësa’s son again and promised that if he was released, they would form a local gendarmerie, paid by the government, as it had been in Biba Doda’s time. But the Ottoman authorities of Shkodra, instead of reflecting, brought as Kajmekam, Hajdar Agë Belegun, who could not stay in Orosh and did not have a defined center. In those conditions, his deputy, based in Orosh and with a salary of one thousand groshis per month, was appointed Captain Gjoni. Other captains and many heads of tribes, at the end of 1873, received titles and thus, apparently, from the Turkish government, the natives were charged with influence, to administer Mirdita, based on the canon there.

However, this “solution” did not work, because the residents mobilized, occupied the paths, in order to never allow alone the encroachment of the Krahina by the Turkish kaymekam. (213)

The Mirditas gathered in their Assembly, in Grykë Orosh, on December 3, 1873, and addressed the High Porte, the consuls of Austria-Hungary, Italy and France, with the request to implement traditional self-government and to return from exile, Their head. On December 3, 1873, 400 mirditas sent a letter to the High Porte and the foreign consuls in Shkodër, with which they prayed that the office of Kajmekam be destroyed and their president, Preng Bib Doda, returned, or at least, to appoint his deputy, then to allow the free application of the Canon and, finally, to call a general meeting of the people of Mirdita in Shpal, in order for the people to be able to formulate their wishes.

Since they did not receive an answer, they, as usual, once again occupied the road between Prizren and Shkodra. Ahmet Rahsimi, settled all the issues with Mirdita, leaving the Mirditas free, to come to the market and releasing all those arrested by Shefqet Pasha, with the exception of the captains’ sons, Gjon and Kola, who were kept under arrest, until the fathers appeared. On March 16, 1874, the prisoners attacked the guard and fled to Mirdita.

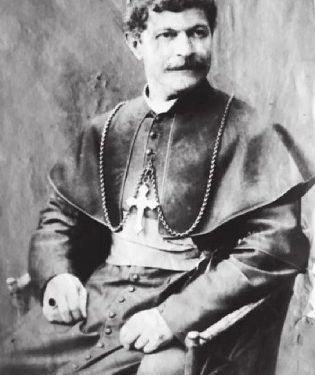

During the summer of 1874, Ahmed Rahsim Pasha was able to secretly send money to the most important leaders of Mirdita and, thus, between Mirdita and the government, some relations developed that could be called good. Not even the second intervention in the interests of Preng Biba Doda, by the Mirditas, pushed by the priest Prend Doçi, in June, could cloud this agreement. (214)

But, taking advantage of the development of events in Herzegovina, they hardened their tone and at the beginning of August 1875, warned that they had decided to take up arms, in case the Sultan did not return the freedom of the imprisoned son of the leader mirditor and to give him the princely inheritance, left by his father. (215)

In December 1875, Captains Gjon Doda and Kolë Prenga, at the head of 400 armed mirditors, after positioning themselves in the village of Naraç, send a written complaint to the local government of Shkodra, with a prayer, to forward it to the High Gate. The same request was made known to the consuls of Austria-Hungary, Italy and France in Shkodra. (216)

“To you who form the Majlis of Shkodra, greetings from the people of Mirdita and from us, its captains: Say and pray to the government of Shkodra and that of the Sultan, regarding what we are sending you next:

We turn first to our Sultan, to let us live in accordance with our Canon. We are very poor and knowing that you cannot donate anything, it is not necessary that you spend your treasures on us.

All the governors who were sent to us with the title of Kajmekamitm were sent against our will and Canon. We demand justice from the injustices we have suffered for seven weeks because we are defending our right to enter the city.

We pray to our God in heaven and the Sultan on earth, to send us the son of Bib Doda, and to give us as his representative, a member of this family, to start ruling over us, as we have always hoped. (217)

The High Gate, despite all the conciliatory tones it used in talks with the leaders of Mirdita, had absolutely no intention of releasing Prengë Bibdoda, much less placing him in charge of Mirdita. Also, she hindered in all ways, the placement of captain Gjon Doda in charge. While the talks about this issue were taking place, according to the official press of St. Petersburg, in many villages, preparations began to rise up against the Turkish government. This caused concern to the government, which knew well that Mirdita was an important military factor and, moreover, around it, other tribes could also join. (218)

On April 28, 1886, in Shënpal of Mirdita, a meeting of the five bajraks of Mirdita was organized, from which a prayer was sent to the Governor General, in which, in addition to their economic demands, they insisted on the autonomy of the province and nurtured the hope that only through it, peace can be ensured in Mirdi. They warned that soon, they would gather again in the assembly, to request the appointment of Prengë Biba Doda, to the post of Captain. (219)

Efforts continued without losing hope. In the month of May 1876, the Mirdites prayed to the Grand Vizier, asking him for the last time, the return of Prengë Biba Doda to the head of Mirdita. (220) In this request, they write: … “For as long as we have had Bibë Dodë Pasha as an administrator, in the population of Mirdita […]. We lived in peace and quiet. Since the death of Biba Dodë Pasha, the Kajmekams appointed to administer us, have had neither the proper ability nor the knowledge of our customs and laws, in this way, all the affairs of the people have been confused and our situation has gone bad and not worse, until this state, very miserable that it is today.

Today that the son of Biba Dodë Pasha, with the kindness of the Sultan, has grown up in Istanbul and received his education in the government schools, we all want him and will be happy to have him among us, since he knows our affairs, our needs and will enjoy the appropriate authority. Therefore, we, the people of Mirdita, ask you to send us the son of Biba Doda, as the president of our country, to ensure our peace”.

The request addressed to the Grand Vizier was signed by the two captains of Mirdita, Gjoni and Marku, from the seven members of the Administrative Council of Mirdita: Prengë Gega, Tuç Nikolla, Ndoc Gjoni,

Tuç Deda, Njac Gjoka, Gjet Ndou and Njac Nikolla. From the flag bearers of the Five Flags: Nikoll Ndreca, Dede Kola, Nikoll Deda, Nikoll Kola and Mark Gjeçi.

From the leaders of Mirdita: Dodë Gega (Jusbash), Captain in the Ottoman army, Kolë Nikolla and Noc Ndreca mylazim and advisers to the local government and from the 40 leaders of Mirdita: Prengë Gjeçi, Ndoc Kola, Gjin Deda, Mark Gjergji, Ndrekë Ndoka, Kolë Ndreca, Nikoll Ndreca, Paç Nikolla, Nikoll Prenga, Gjet Prenga, Nik Biba, Ndrec Mark Pici, Ndre Marka Nika, Gjet Marku, Ndrec Marku, Kolë Biba, Gjet Marka Preni, Kol Marka, Pjetër Gjoni, Mark Kola, Prend Pal Noci , Col. Gjek Gjini, Ded Grabi, Prengë Nikolla, Marka Deda, Col. Ndreca, Nikol Kola, Mark Tokri, Nikoll Prenga, Frrok Deda, Preng Deda, Dodë Prenga, Mark Ndoci, Prengë Marka Preni, Gget Gjergji and Pjetër Prenga. As can be seen from the number and affiliation of the signatories, Mirdita, in terms of the choice of its leader, is already united. (221)

Even the mother, Margjela, whenever she had the opportunity, asked the consuls of the Great Powers for the son’s return to his homeland. Likewise, Abbot Doçi used all the personal connections he had with foreign diplomats to internationalize the problem of Biba Doda’s son and his return to the Motherland. Even the chiefs, who had not accepted anyone else as their Chief, had merit. There came a moment when the Mirditas were not only ungovernable, but also dangerous. They became potential allies, with all the peoples rising up against the Ottomans.

The expected war with Montenegro and the opposition to send its own contingent of fighters against the Montenegrins, without the return of Bibë Doda’s son, caused the High Gate to return Prenga to his homeland and to make his return as soon as possible. dignified, by decree of the Sultan, in July 1876, he was given the rank of Brigadier General and the title of Pasha. (222)

At first glance, it seemed as if the High Gate was sending Prenga to Albania to take over the functions of his father, but in reality, he kept him semi-arrested in Shkodër. His Palace and all the people who went to see him were under strict surveillance. After his return, Prenga enjoyed the formal respect of the Ottoman authorities of the Vilayet, but he was not free. The Mirditas experienced this lack of freedom as a great injustice. Memorie.al

- Bibë Doda Fund, file 15, p. 17

- Schëanke, Zur Geschichte der österreichisch-ungarischen Militärverëaltung in Albanien (1916 bis 1918), doctoral thesis, University of Vienna 1982, p. 74.

- Franc Baron Nopça, Travels through the Balkans, p. 472204. Schëanke, Zur Geschichte der österreichisch-ungarischen… p.449

- Bibë Doda Fund, no date, file 17, p.2

- Ndoc Nikaj, Memories of a past life, … p.25

- Ndoc Nikaj, Memories of a past life, … p.26

- History of Albania, Volume II, year 1984, p

- Ndoc Nikaj, Memories of a past life, … p.50

- Merita Sauku-Bruçi, Elena Ghika and Girolamo De Rada, … p. 24

- PA.Vj.34-43, Report of the Austrian Consul in Shkodër, Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Vienna, Shkodër on August 3, 1875.

- Kolona Çekaldi, consul of France in Shkodër, Duke Dëkaz, Minister of Foreign Affairs of France in Paris, on April 5, 1876, SA/LSHP/DAP, Shkodër, on April 24, 1876, Doc. No. 4, Ligor Mile, Albanian League of Prizren in French documents, vol. I-II, Tirana: 1978-1979

- Simon Prendi, History: The Middle Ages, New Age and Today, p.73

- Franc Nopça, Highland Tribes… p. 94-95

- Saint Petersburg Gazette, No. 203, August 3, 1875, see Luigj Martini, Abbot of Mirdita Prend Doçi,…p.69

- Luigj Martini, Abbot of Mirdita Prend Doçi,… p.55-56

- Luigj Martini, Abbot of Mirdita Prend Doçi,… p.56-57

- Luigj Martini, Abbot of Mirdita Prend Doçi,… p.72

- Luigj Martini, Prince without a throne of Mirdita,… p. 168

- LPK. Consulate of France in Shkodër, vol. 20, p. 119-120, Albania in the years of the Albanian League of Prizren, volume I

- Luigj Martini, Abbot of Mirdita Prend Doçi,…, p.73-75

- AQSH, “Prengë Bibë Doda” Fund, File 1, h.1; Luigj Martini, Abbot of Mirdita Prend Doçi,… p.81