By Sven Aurén

Translated by Adil N. Bicaku

Part twenty-five

ORIENTI EUROPE

Land of Albania! Let me bend my eyes

On thee, thou rugged nurse of savage men.

Lord Byron.

In the book “Orient of Europe”, the author of the work is the Swede Sven Aurén. They are impressions of traveling from Albania from the ‘30s. His direct experiences without any retouching.

In a word, the translation of the book will bring to the Albanian reader, the original value of knowing that story that we have not known and we continue to know it, and now distorted by the interests of the moment.

Now a little about what these lines address to you: My name is Adil Bicaku. I have worked and lived for over 50 years in Sweden, without detaching for a moment, the thought and feeling from our Albania.

I am now retired and living with my wife and children, here in Stockholm. Having been for a long time, from the evolution of the Albanian language, which naturally happened during these decades, I am aware of the difficulties, not small, that I will face, to give the Albanian reader, the experiences of the original.

Therefore, I would be very grateful if we could find a practical way of cooperation together, to translate this book with multifaceted values.

Morally, I would feel very relieved, paying off part of the debt that all of us Albanians owe to our Albania, especially in these times that continue to be so turbulent.

With much respect

Adil Biçaku

Continued from the previous issue

THE STRIKE SHAKES TOWARDS NORTH

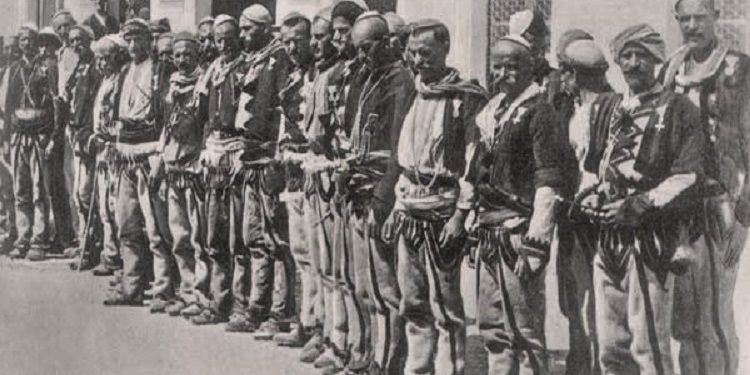

The women wear a small, wrinkled black hood on their head; the chest is covered with strings, medallions and buttons. All men have belts wrapped around the waist, with strong red dyes. Some of them even tied pieces of cloth around the blanket and look like Arabs. Women in their frozen, ugly clothes and black charcoal, straight bangs that go to the Greenland Eskimos. Those few ethnographers who have taken the trouble to study this parade of clothing colors must have felt as if they were in paradise.

Look at those two men over there, who buy some refreshing water, from the water seller, with the shiny brass pot! It’s no coincidence that one man’s pants, black embroidery, follow a different twist than the other. Every banner, every village, has detailed provisions on how men and women’s clothes should be. This is a whole science, to distinguish and classify the successive variants of Albanian clothing, a science, which would be enough to secure the fame of a diligent researcher.

But we, who are not ethnographers, but only a few simple Swedes, who are lucky enough to travel to a forgotten place, do not worry about the subtleties of variation. We enjoy the grandeur of the fun colors of the shopping street and think about the weird, that here in a small town, near the Adriatic Sea, we have the opportunity to experience a birthplace, with fame and atmosphere, like a fairy tale of old Persian. After entering the sports chapel in Constantinople and turning the bazaar of the Bosphorus city into a Turkish copy of the Paris antiquities bazaar, the Shkodra bazaar has become the last in Europe.

How many years will it take before the colors disappear, the goods are industrialized, before one is satisfied with the imagination and the former splendor, for any “Skansen” in Tirana? And how long will tourists still buy Albanian art objects, at high prices, in the beautiful shops of Ragusa, instead of looking for that orientation, which no one talks about? In the Shkodra bazaar, foreigners go into ecstasy from embroidered capes, miracles of weapon processing, sleek watermarks. But foreigners are made up in many cases, of Yugoslav shoppers, who are sure that tourists on the Dalmatian Riviera are more willing to pay for their purchase, at multiple prices, buy and buy so that the bazaar will soon be emptied.

In the evening, Koliqi invited us to a small dinner. To give us a special respect, dinner will not be eaten in the usual canteen of this restaurant, but in the party hall, where its master, quite careful, had set a slippery table, in the middle of a room, as a sea. There is no furniture other than this table and three chairs. Our small group is a pleasant oasis in a desert, without end. The waiter is presented as a vision far on the horizon, when he starts the step with those dishes fulfilled.

But if the great hall is empty, the ceiling is more solemn. During a tight string, red, yellow and green stripes are twisted into a mixed mass. When I, as required by the label, proposed a toast to King Zog of Albania and the gentle Koliqi returned it, proposing another to the brave King, Christian, of Sweden, then I asked about the decoration of the ceiling.

-They are still hanging since when here, we had a ball of masks fourteen days ago, explained the master of dinner.

In fact, I know that Muhammadan Shkodra, however, is a very advanced society, that the relations between the sexes allow the organization of holidays, where ladies and gentlemen, come together as guests, but the explanation seemed strange to me. When a western lady, will go to the masquerade ball, then she takes on a simple Muhammadan character, covering her facial features. But what does a Muhammadan woman, who is always disguised, do? I saw God, but how is it done in a ball of Muhammadan masks?

But Koliqi, raise the glass, raise a health for the future of Albania and does not seem ready to discuss the problem of the ball of Albanian masks. We change the subject and argue for today’s Albania and yesterday’s Albania, and for the future of small states, in a tense and intriguing Europe.

***

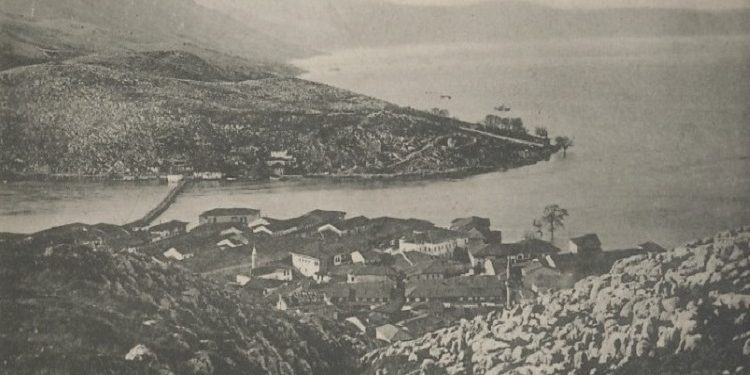

One sunny morning, we drive to the large airport, which lies a mile outside the city. Nature has forgiven Shkodra the aerodrome: a wide, light green wasteland, on one side is bordered by the blue mirror of Lake Shkodra, on the other, the powerful massif of Alps with different colors of fascinations. During the first ascent, the color of the mountain, goes like a mixture of gray and tile, above it is absorbed that kind of strange paint, from magnificent shades of blue to dark and above all, where the sky is clear and shining, the shadows turn into snow dazzling white.

Down the mountain, in the extreme corner of the aerodrome, flows the Drini poor in water and slow in its deep bed. An old Venetian bridge helps the national road over the other side of the river, such a beautiful and harmonious bridge with wonderful divisions, of arches and arches should be emphasized as one of the greatest values to see, Shkodra. I have seen many beautiful bridges in this country, which is the peculiarity of romantic bridges, but none as brilliant as this.

Aside from the way it is set up and getting inside the wild landscape, it looks more like a fairy tale than a reality. Ah, if only I could sit here one evening at dusk and see the picturesque countryside, return home to their mountains, in a row on its narrow ridge! It should be a fantastic silhouette. Besides, I am not the only one who admires the bridges of Albania. Albanians themselves love them just as much and have chosen one of them, for a motive in their banknotes.

Yes, goodbye beautiful bridge of the Drin! In the middle of the green wasteland, stands the simple building of the airline firm’s offices and on its pillar, with the traditional waving indicator, of the direction of the wind blowing, like a festive Japanese balloon. Nearby stands already ready to take off, the plane with white silver wing and the sound of propellers. This is a car, very good with elegant equipment and seating for six passengers. Those gentlemen, to whom we have entrusted our lives, are two Italian pilots, with elegant thin mustaches and hands with plenty of cure.

The plane and the flying firm are also Italian. The ticket price is low. The Shkodra-Tirana road costs only 15 gold francs. We are now sitting in our comfortable armchairs and laughing at Koliqi, who stands outside the cabin window and wishes us well, both with scarves and hats. Engine noise becomes a little louder. The green field with the offices of the airplane firm and our friend, gesturing suddenly sit down below us and with furious speed; we rush inside straight into the high alpine path.

When I open my eyes again, we are very high in the cosmos, high above the blue lake of Shkodra and the white city. Roads, houses and gardens shrink altogether and disappear. Rozofat is reduced to a bulky hillside, on the bare slope of Tarabosh, military roads form a pattern of thin tombs. From the west, I see the wide Adriatic Sea and small fishing boats, with red sails in the dark.

Inside the country of Albania, our bird whispers.

Down there gigantic giants crawl like, thick, twilight, naked, inhospitable, uninhabitable serpents. In those dense valleys, the greenery shines and there I also see from a rustic field, with the corn storehouse, stacked in straw huts, which look like beehives, from here from my point-of-view in the air. Above those gray-black mountains, a long serpent extends, as if a random ball had been thrown. There is a serious look to this landscape, a face full of wrinkles. It is not that kind of landscape, which attracts friendly smiles, on the lips of the spectator or puts it in the atmosphere of an idyllic romanticism.

This is a picture that would seem to him endless and impressively impressive. But it has its own charm, these rugged Alps, with their vertical ravines and dark moving shadows in blue. They have the fascination of unbearable risk. Saturated Englishmen from the walks of the world, usually occasionally, come here to seek the romance of isolation. I understand them very well, just as I understand Mrs. Haslock from Elbasan, when she swings her ass on the road, along the completely hidden rock paths. This is the adventure that makes me hand here deep under me.

Man has a habit of saying that time stands still. Perhaps the expression has become a bit consumed in the corners, but in this mountainous terrain, time has remained in place, to the extent that it has lost its meaning. Small houses look just like they did a hundred or two hundred years ago. Its inhabitants dress and live, under the same conditions, now as then, according to the same unwritten but living laws. The mountain has given them a view of life, has created these strict, uncompromising concepts, on honor and dignity, and has cemented strength in their arms and steel in their judgment. Tradition, poverty, nature have turned the sons of the mountains, into personalities.

I said sons of the mountains?

This is wrong. Albanians are not the sons of the mountains, but of the eagles, those proud Albanian eagles, which stand as casts, in iron in the piles of stones or crawl down, in the gorges for hunting. In the Albanian language, there is no such thing as Albania. Albania is called the country and Albanian is called Albania. Albanian, meaning ‘ern’ and Albanian, is “eagle origin”. A proud name, of a proud people. Albaner, is a completely European name for the Albanian people. The Turks call them Arnauts. They call themselves, as we said, Albanians, although this name is used only within the country. In the eyes of the world, Albanians are Albanians and use this word when they talk to foreigners.

We have passed Kruja, but the place of adventures is still the same. Without stopping, new mountain slopes, rising high on the horizon, is just the shape of the silhouettes that changes. Like an angry cat, an original Albanian bridge is distorted, over a dark ditch and on the narrow ridge of that bridge, three men on horseback appear. There are three highlanders, on the way to Tirana. Other people I do not see.

But I know that there are people and I know their abilities, their tribal feelings and clan solidarity. Maybe they are even blood byrazers, those knights down there. Byrazerllëku, is a living reality, just like blood feuds, in the country of Albanians. Especially here in northern Albania, they want to forge the strongest friendship known in the Balkan tradition. I have heard about this blood brotherhood, talked about on many occasions, and in Shkodra, I managed to find out about the ceremony of this act.

But it was not Koliqi who gave me that information. Koliqi confirmed very briefly, the existence of byrazerlëkut, but did not want to go into details of the topic. Like all educated Albanians, he thought that bureaucracy belonged to that Albanian habit, with which a foreigner, if possible, should not be confronted. He was a simple but language-savvy merchant who told me about the forms that must be followed for two men to become blood brothers.

The way is this: each one of the parties, tie a cloth belt around the little finger of the right hand. Then cut the unprotected part of the fingertip, with a knife, thus causing two good wounds. The blood drips into a large glass of brandy, which is then drunk by both together. With this the blood brotherhood is established and the tribe usually, organizes a feast to celebrate the union and the obligations taken. Obligations are very important: the life of the brother-in-law is more valuable than he, the wife of the brother-in-law, is even more invulnerable, that of the brother of one belly, the brother-in-law has ruled out the possibility of blood feuds between each other.

But, this informed man explains to me, bureaucracy as such, is not a typical Albanian feature. This young is found in many other Balkan countries and is known by the Slavic name, probatin. On the other hand, simply Albanian is the tradition of godfatherhood, which establishes one of the effects, equally strong and even stronger union, but which is related differently. You become a godfather, there is a desire and honor, to first get the hair of the youngest child, the friend.

The ceremony is usually celebrated when the child turns one year old, maximum two years old. The mother and father of the child, together with the child, go to the friend’s house and after receiving various gifts, usually a beautiful robe and very hot bread; the friend cuts the child’s hair, which he then burns. He is now the godfather of the father of the child, which means, he stands closer to him than the brotherhood and he in the capacity of honorary member of the family, is allowed to enter the harem, something that except the owner of the house, is forbidden to any man.

Many times these brotherhoods are connected between men, with respectively different religions. The tradition of the godmother is based on any kind of religious division. Of course, there has been no lack of opposition to this custom. The Catholic Church in particular, has made great efforts, to take the tradition of godfatherhood out of use, but at least so far, without success. An Albanian man must have a godfather. This is what prestige demands. Memorie.al