By Agron Alibali

Part Two

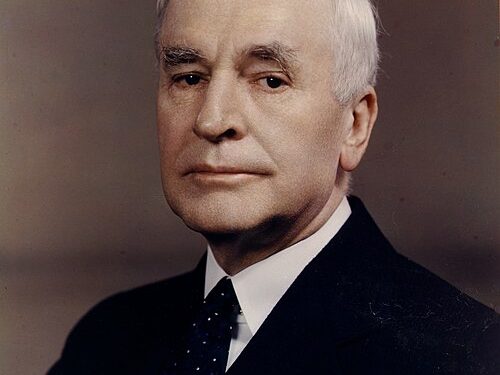

Memorie.al / On the evening of December 15, 1942, at 7:30 PM, an entirely unexpected phone call arrived at the office of the head of the FBI, Mr. J. Edgar Hoover, in Washington D.C. The caller, an individual with many titles, whose identity is still kept secret in the American archives, reported that Faik Konica had been found dead in his apartment in the American capital that day. The informant further stated that he “had received information that several unknown persons were removing Konica’s personal belongings from the house without performing the proper formalities.” He said he had tried to contact the State Department, but his attempts “had been unsuccessful.” For this reason, he requested that the FBI “intervene to stop these actions.” The official who took the call and noted the specific request politely replied that “the Bureau did not have jurisdiction in such matters.”

Even 18 days before:

Indeed, on that same day, November 28, 1942, i.e., eighteen days before his death, Konica wrote to Earl Brennan and asked the United States “to denounce the recognition of Italian domination, implicitly accepted by the policy of ‘appeasement,’ and to recognize King Zog as the legitimate head of the country,” because “as a result of the forced course of events, [Ahmet Zogu] had become a symbol of Albania’s independence – and thus he must be preserved at all costs if the past and present are to be kept uninterrupted.”

It is understood that Noli and Konica, as two rare statesmen, diplomats, and scholars, were clear that the circumstances created after the invasion by Italy had violated the continuity of the Albanian state as a subject of international law. The uncertain situation on the ground and the non-recognition of a government-in-exile by England endangered the very existence of Albania.

We do not have Konica’s letter to Brennan in full, but surely he must have also requested a clearer declaration from the United States regarding Albania’s independence and territorial integrity after the war, in accordance with the joint position with Noli of November 19, 1942.

Of course, in the context of encouraging resistance against the Italian invader, the OSS itself had its strategic objectives in Albania. The alignment of these objectives with the goals of Noli and Konica may have been a factor in ensuring that the efforts of the two wise men did not remain without effect.

Even 16 days before:

Indeed, on November 30, 1942, or sixteen days before Faik’s death, the OSS would mobilize the State Department itself to issue another declaration for Albania. The event is described in a document by Adolf A. Berle. Jr., Assistant Secretary of State of the State Department:

November 30, 1942

Eu – Mr. Atherton

PA M – Mr. Murray

Frank Sayre stopped here and explained that the Office of Strategic Services was making plans for [inciting] political warfare in Albania.

Mr. Brannon (sic), of that office, has drafted a project letter, which he hopes the OSS will transmit to the Secretary of State. The copy is attached.

In short, the gist is that he is ready to request a declaration from the United States to state that independent Albania will be re-established after the war, which will help to encourage guerrilla warfare there.

Brannon, as well as Frank Sayre, are convinced that, at the very least, there is a possibility that Great Britain is involved in unofficial talks with both Yugoslavia and Greece, with the aim of partitioning Albania between them.

I would be very happy to have your opinion on the above.

A.A.B. Jr.

Indeed, Brennan presented the State Department with a two-point proposal, which essentially coincided with the views of Noli and Konica. In the first point, he “requested the issuance of an early authoritative declaration in support of the cause of an independent Albania.”

This, he continues, “will facilitate military cooperation with guerrilla leaders fighting against the Italians” and will constitute “100% moral support for Albanians inside and outside the country.”

In the second point, Brennan “hoped that the [State] Department might deem it appropriate to recognize as a symbolic entity some group to represent the aspirations of the Albanians, whether simply as an Albanian representative committee or as a government-in-exile.”

Brennan emphasized that the group should be “strictly non-partisan” and “be committed that the question of the [legitimate] Government must await the end of the war.” Brennan, furthermore, spoke against the leadership of this group by Ahmet Zogu, countering the argument that Zogu could still “claim the existence of a right to reign which has not expired de jure.”

Even 12 days before:

On December 3, 1942, when Faik had less than two weeks to live, the Directorate of European Affairs in the State Department transmitted to the Secretary of State the “suggestion” for a declaration in support of Albania, thus endorsing the “first and principal recommendation” of the OSS.

Regarding the second request, it considered that “it was not so urgent,” that the Albanian diaspora remained divided, and that “we are not convinced that the recognition of an Albanian Committee would be useful.”

On that same day, Director J. W. Jones would present the final proposal of the Directorate of European Affairs for the Declaration on Albania to the Secretary of State, along with the corresponding draft text.

Even 4 days before:

On December 10, 1942, i.e., when Faik Konica had four days left to live, Secretary of State Cordell Hull read and distributed to the accredited press at the State Department the historic Declaration in support of the aspirations of the Albanian people for freedom, independence, and territorial integrity. The text compiled and proposed by the Directorate of European Affairs according to the ideas of the OSS had been approved without any changes.

“The Government of the United States is not unmindful of the continuing resistance of the Albanian people against the Italian invaders,” Mr. Hull would declare. “We admire and value the efforts of the various guerrilla groups fighting against the common enemy in Albania.

The Government and people of the United States look forward to the day when we can give these brave men all effective military aid to free their country from the invader.”

“In accordance with the clear and unvarying policy of non-recognition of any conquest achieved by force, the Government of the United States has never recognized the annexation of Albania by the Italian Crown. The Joint Declaration of the [American] President and the British Prime Minister, of August 14, 1941, known as the ‘Atlantic Charter,’ emphasizes the following:

‘Third, they respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those [peoples] who have been deprived of them by force.'” The restoration of a free Albania is also provided for in that principled declaration.

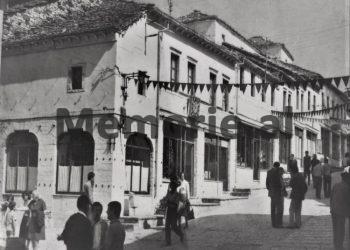

The Declaration was received exceptionally warmly by all the Albanian people, under occupation or in the diaspora. As rarely before, one of the most important diplomatic activities in the history of Albania had been thus crowned with complete success.

However, the weight of age, the constraints and stress of daily life, and especially the troubles of Albania, were silently burdening the health of the great Faik. “I met him on the street about a week before he passed away,” Harry Gratan Doyle, his classmate at Harvard University, would write. “He seemed old, tired, and not very optimistic,” he continues. “The temporary disappearance of his country as an independent nation was a very severe blow to him…” But his death was sudden and shocking. He had so many friends here.”

Even the final day:

December 14, 1942, was a Monday. We do not know if Faik stayed home that day or was busy with some work in the city where he had served for so many years. Shortly before 5:00 PM, Konica would suffer a cerebral hemorrhage. Around 5:30 PM, his secretary, Charlotte Graham, arrived there. Faik asked her to call his doctor and close friend, Dr. Robert Oden, who arrived without delay. After examining him, he confirmed to the secretary that “Konica was in an extremely serious condition.”

While waiting for medical assistance and hospitalization, he would pass away in the early hours of the morning in his apartment in Washington, D.C. As silent witnesses to Faik Konica’s life in the American capital, the walls of his handsome apartment were adorned with shelves full of rare books, as well as paintings and other valuable items.

On that day in mid-December, Faik Konica’s precious library, consisting of more than 2,500 volumes, would lose its owner forever. And later, it would lose itself as well. In the apartment’s sitting room, a marvelous portrait of Faik, the work of the well-known American painter of Polish descent, Joseph Sigall, would remain the most vivid and tangible image of the great Faik, now lost, for his many friends. / Memorie.al