By Njazi Xh. Nelaj

Part Two

Memorie.al/ Impressions and memories from the life of the talented pilot, the tragic figure, Colonel of the Air Force, Niko Selman Hoxha, who fell in the line of duty on November 20, 1965, at the military airfield of Rinas, during a combat exercise with a ‘MIG’-17 F jet, in front of the regiment’s personnel and some military academy cadets. The impressions and memories were collected by Niazi Xhevit Nelaj in June–July 2012, in Vlora, Tirana, Voskopoja, etc., during meetings with people and phone conversations, as far as distant Boston. Every meeting and conversation with Niko Hoxha’s contemporaries and close relatives has been reflected in the material with fidelity and authenticity. The monograph reflects only a part of the hero’s life, the part connected to aviation and flying, and does not extend to other spheres of the multifaceted life of the man who gave impetus to military and aerial discipline and training. Niko Selman Hoxha, as he was orderly, disciplined, and extremely correct in the regiment, also stood out for his exemplary lifestyle. He did not live in the regiment or eat in the pilots’ quality mess but stayed with his family, thanks to the dedication and good management of his wife, Jolanda, who ensured that his routine lacked nothing. This writing does not cover Niko’s family life, nor does it touch on his care for his sons, Valeri and Sasha, whom he left still young but whom he surrounded with great parental care and love while he was alive. Other writings that will follow will certainly shed light on those aspects of Niko Hoxha’s life that have remained somewhat in the shadows in this monograph.

The Author

Continued from the previous issue

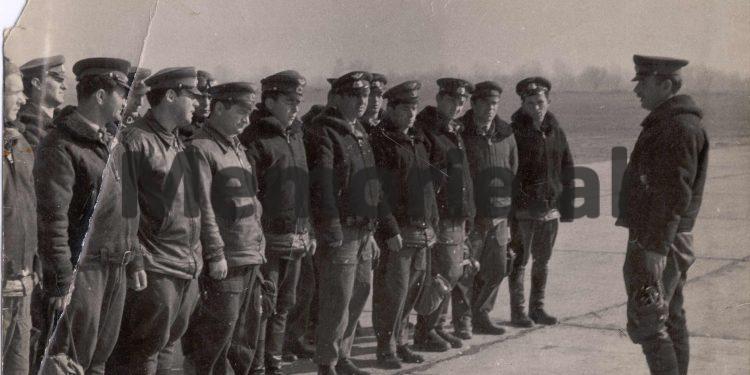

I extended this a bit with this introduction, a kind of exposition, but I can’t help it! This is how the memories come to me, even though so many years have passed. Niko Hoxha spoke, and the regiment stood silent before him. The commander, with a ‘MIG’-17 F fighter jets, after checking the weather conditions in the air, gave instructions on how to act at every moment and place. As veteran pilot Çobo Skënderi recalls: “Niko Hoxha himself conducted the ‘obljot’ (weather reconnaissance) and did it perfectly.”

“When he landed and gave us instructions before the flight, Niko would explain in detail the flight conditions, the system, and the landing, providing us with complete information. He would tell us where there were air turbulences, where there were discharges and where pilots had to turn off the radio, how thick the lower layer of clouds was, and the cloud layers along the route (air path), what the wind was like and its influence, both in the air and during landing, etc.”

The Colonel spoke clearly, beautifully, fluently, in pure and rich Albanian, with scientific competence and knowledge, and in a distinct Southern dialect, with a sweet, melodious voice. His instructions, in this case, were concise and precise. The time until the planes would take off was limited (a few minutes), and the commander aimed to take up as little of his subordinates’ precious time as possible. This was also an undeniable quality of the Colonel.

We were young, in our twenties, as was the regiment itself, which had been formed just a year earlier. I was seeing Niko Hoxha for the first time. I wasn’t just looking at him—I was “absorbing” him with my eyes. Certain distinctive features and qualities of his became deeply ingrained in my mind and have remained unforgettable over time. First and foremost, I was struck by his tall, well-built, and very elegant physique. He wore his flight suit with grace. The commander stood firmly on his feet, slightly apart, with a natural pride and seriousness that suited him. The regiment’s personnel, lined up in front of him, listened intently, as if absorbing every word and instruction that came from the man’s mouth.

The Colonel did not strike arrogant poses but spoke simply, clearly, and sparingly. His words were few but carefully chosen. Every word he spoke “hit the nail on the head,” was timely, and was conveyed to his subordinates with gentleness. Vangjel Koçi, a veteran officer who began pilot training in the Soviet Union in 1960 and later worked as a synoptician in Albania did not live or work with Niko Hoxha for long, but the Colonel’s unique voice remained etched in his memory. When I spoke with my friend in Voskopoja, he told me: “Niko Hoxha spoke beautifully; his melodious voice resembled the song of a nightingale.” How deeply felt is the regard of this simple, highly intelligent, and courageous man!

The Colonel’s voice was perhaps one of the most striking qualities of this irreplaceable man. It was a pleasure to listen to him speaks. His tone was clear, strong, and pure, like spring water, understandable to all who heard it, concise and melodious. Here’s how pilot Serafin Shegani remembers this quality of Commander Niko Hoxha: “In the early 1960s of the last century, my comrades and I were flying at the airfield of the city of ‘Stalin.’ When we were in the air, we would often tune the radio to the working channel of Rinas Airfield, just to listen to the beautiful voice of Niko Hoxha, who was directing the flights of the regiment he commanded.”

I have heard that unique voice countless times, both on the ground and in the air, and I have always marveled at it. In this regard, I consider myself privileged.

The sweet timbre, the melodiousness, the warmth, and the softness, like Chinese silk, of that voice—I can never forget it. Even after so many years, in moments of calm or in sleep, it feels as though I can still hear the beloved voice of the Colonel, who has been gone for many years. That’s why I say with certainty that Niko Hoxha’s voice came to me through the headphones as something extraordinary, with unparalleled clarity and sweetness. What was so special about that man’s voice? I’ll try to list a few qualities; though I’m convinced I cannot capture them all in this modest writing. I say this because the qualities of the Colonel’s voice, in the specific role of flight leader, are perhaps unique and difficult to replicate.

Anyone who has heard that voice through the headphones of a headset will find it hard to forget or compare its sweetness, calmness, clarity, precision, and authenticity. The Colonel spoke to the pilots, especially those in the air, with calmness and gentleness. It’s a well-known slogan in healthcare that “calmness heals.” This is more than true. But in our case, when the flight leader communicates with the pilot in the air, the value of calmness multiplies and, in some cases, becomes lifesaving. It’s certain that Niko Hoxha’s voice, when it reached the pilots in need through the headphones, helped them navigate out of danger and difficult situations.

The Colonel was a first-class military pilot. He held the highest level of qualification as a pilot and was almost constantly in the role of flight leader. Niko Hoxha carried on his shoulders a vast experience of flights in various types of aircraft and in highly challenging weather conditions. The Colonel flew jet aircraft such as the ‘MIG’-15 Bis, ‘MIG’-17 F, and the supersonic interceptor ‘MIG’-19 PM, equipped with air-to-air missiles, during the day in simple weather conditions, during the day in clouds, at night in simple conditions, and at night in clouds.

Before flying jet aircraft, the commander had gone through helicopter aviation school, where he had flown various types of fighter and bomber aircraft. The Colonel had been familiar with the air and aircraft since just after World War II, in Yugoslavia, later in the Soviet Union, and finally in Albania. During his career as a pilot, the commander must have encountered difficult aerial situations, which he overcame thanks to his outstanding character and skills as a pilot. Thus, when he took the microphone as the flight leader, Niko Hoxha knew what to say and how to guide the pilots who needed his help.

When communicating with the pilots, the Colonel became more serious, quickly assessed the situations the pilots were experiencing in the air, made decisions in the blink of an eye, and intervened promptly and tactfully, offering precise, well-chosen words to the pilot in need, thanks to his quick reflexes. But these alone would not have been enough if the Colonel had not followed every flight meticulously, step by step. Niko Hoxha knew the individual characteristics of the pilots he led in detail and spoke the right words at the right time, with precision, according to the aerial situation. Niko Hoxha’s advice was something to “take to heart” and helped pilots navigate out of difficult situations.

The Colonel was a courageous pilot with rare determination and perseverance. He wanted to fly all types of aircraft available to the regiment. Through self-taught methods, without attending special courses, Commander Niko mastered flying the ‘MIG’-17 F and ‘MIG’-19 PM jet aircraft. The position of flight leader in aviation is unique and delicate. It’s worth revisiting this point in more detail. Niko Hoxha was perhaps one of the most accomplished flight leaders the Albanian aviation has ever known. His warm voice brought “warmth” and “security” to the cockpit of the aircraft in the air. When communicating with the Colonel, the pilot felt as though he was right there, in the cockpit, completing the flight together.

Niko Hoxha never spoken words of “harm,” but rather spoke with competence and responsibility, and the pilots trusted his guidance. This had been proven in practice, not just in one instance. Commander Niko gave precise instructions to pilots in the air, avoiding unnecessary noise over the radio, which only causes confusion and chaos. Niko’s warm words brought comfort and optimism. I had heard him intervene dozens of times to assist pilots, and I was always amazed by that distinctive voice of his. I experienced it myself on one occasion.

During a training flight over Rinas Airfield, I was practicing “aerial combat” in a pair of aircraft. In formation, my colleague Llazar Çupa was leading, and I was flying behind him. My task was to get “on his tail” and attack, while filming. The Colonel, in his role as flight leader, was observing us from below. I was a young pilot, enjoying myself by maintaining formation, but my task was to attack. The Commander was not pleased with my performance, so he took the microphone and intervened carefully: “75, get on his tail and attack, you’ve turned into a satellite!” I heard him and tried to correct my mistake. The Colonel’s gentle communication with the pilot in the air did not cause alarm or anxiety but rather calmed and encouraged them to act correctly.

There are countless instances where the Commander stood by his subordinates in difficult situations and helped them navigate out of trouble. Perhaps I wouldn’t have started this portrait-writing about our hero now if it hadn’t been for the encouragement of a noble and courageous Lab woman, a descendant of Niko Hoxha’s ancestors from Tragjas. The woman who encouraged me is named Nurhan. An interesting name, even a bit unusual and rare. She is Niko Hoxha’s niece, the daughter of the Xhuveli family from Tragjas. Around mid-June of this year, I went on vacation to Vlora and stayed with my family in a villa in Ujë të Ftohtë. It was the home of Nurhan and her husband, Lavdosh.

The intelligent Lab woman had learned about my former profession, and one day she naturally asked me: “Were you a pilot?” Yes, I confirmed, somewhat distracted in the conversation. “I had an uncle who was a pilot, maybe you knew him,” she said. What was his name? I asked. “Niko Hoxha,” she replied. A shiver ran through my body, and my mind took me back to those distant ’60s of the last century. I quickly composed myself and turned to my interlocutor, who had taken on a solemn, slightly sad expression. “Niko Selman Hoxha, from Tragjas,” I said. The woman’s eyes widened, and she exclaimed: “What, you knew him?!” When I told her that I had once worked with Niko Selman Hoxha, she was overcome with joy and pride at having met someone who had worked with her late uncle.

Gradually, our conversation grew livelier, and the 60-year-old niece of my commander began to tell me about the hero’s life during his childhood. When her mother was alive, she had left Nurhan a legacy, which, with a mix of fear but always pride and a touch of nostalgia, she entrusted to me as her intimate secret. “When you meet Niko’s friends,” her mother had told Nurhan, “respect them and hold them in the palm of your hand.” And she had sworn her to it, a vow that Nurhan did not take lightly: “By Niko’s bones,” the old woman of the Xhuveli family had sworn before passing away.

Through her stories about the Colonel’s life as a child and adolescent, Nurhan, simple yet strong-willed, drew me into the depths of writing about the hero, giving me a strong push to undertake a task that was challenging for my current capacities and health. I thought to myself, “I’m not entirely unlucky!” After Nurhan, retired pilot Bahri Meshau, whom I’ve known for over 50 years, spoke to me about the Colonel and took me to the home of retired pilot Guri Merkaj in Vlora. Guri had been one of the most distinguished pilots in our aviation during the 1960s, but after a serious illness, he had recently become completely blind. We visited our friend at home and spoke to him.

Bahri recognized me, but Guri did not. I reminded him that we had once worked together as flight instructors at the Pishpora field airfield, and I even mentioned our students and colleagues, but Guri had forgotten my voice. It had been a long time since we had seen or heard from each other. Then I reminded him of a detail from his flights at Rinas Airfield, where Guri often landed near the turn of the civilian airport, and the spot where the wheels of the ‘MIG’-19 PM he piloted touched the concrete was nicknamed: “Guri’s T.” After this detail, my friend remembered, stood up, and shouted: “Njazi, you’ve given me a wonderful surprise! I didn’t expect you to visit me today.” The elderly pilot was delighted.

We talked freely about various issues, in the coolness of the room where Guri stayed that hot summer day, under the “monitoring” of his teenage grandson. I asked my friend if he remembered Colonel Niko Hoxha, and he, after adopting a more careful and solemn posture, became more serious, cleared his throat, and said: “Niko Hoxha was a man of trust and kept his word. I remember him as a proper commander and a true man.

In flight, he gave us, the young ones, initiative. What he said, Niko Hoxha did. His Yes was Yes, and his No was No. He joked and laughed until tears came when his subordinates joked with him.” The candid recollection of the Colonel, who was killed before our eyes, was concluded by the retired pilot, Guri Merkaj, with a deep sigh. He declared: “Men like him don’t come easily to this world!”

I bid farewell to my friend after so many years and left him with a sense of relief in my soul, taking with me an unusual enthusiasm and inspiration. I made up my mind: “I will dive into this work resolutely to write this hero’s portrait.” As I walked through Vlora with Bahri Meshau, observing this city that I had seen grow and change over different periods and now finally healing, my mind was flooded with all kinds of impressions and episodes from our shared life and work as pilots, with Guri, once in Rinas and later in Pishpora and other aviation units.

In the spring of 1966, during a methodological course for flight instructors, Guri wrote in my notebook, with details about the construction and operation of the MIG-15 aircraft, in clear and beautiful handwriting:

“Njazi, the waves of life brought us together, and then they separated us again. I leave you this note as a keepsake from me, your unforgettable friend – Guri Merkaj.” I kept that notebook for a long time, like a precious relic, but unfortunately, it got lost somewhere along the way, and I no longer have it. The uniform on that born soldier’s body shone. He wore the military uniform with pride, as if he was born to lead the unit, both in the air and on the ground. At first glance, Niko Hoxha gave the impression of a talented athlete and gymnast. Everything about him seemed perfect, as if crafted by an artist’s hand. Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue.