By Fabio Bego

“The security announced about Charles, that he propagated Western music, committed immoral acts, with Albanian and foreign girls, such as those from the Polish, Bulgarian and…”/ –

Memorie.al / In Albania, the last waves of emigration from Africa have raised questions about the notions of hospitality and racism in the country. Encounters between Albanians and Africans in Western Europe highlight the ethno-racial difference between “diasporic” communities as they struggle for recognition and resources. But how did communist ideology mediate relations between Albanians and Africans in the past?

Albanian connections with anti-colonial figures

Socialist Albania was a vocal supporter of anti-colonial struggles in Africa and established relations with several newly independent states. The symbols of the independence movements, such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and Haile Selassie, from Ethiopia, visited Albania.

The end of colonial rule in the early 1960s coincided with the deterioration of Chinese and Soviet relations and the breakdown of Albanian-Soviet relations. Albania strengthened its relations with the People’s Republic of China under the leadership of Mao Zedong in an attempt to create a front against Western capitalism and Soviet “revisionist” influence in Africa.

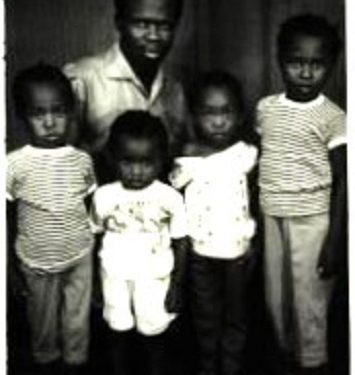

Through diplomats in Accra, the Labor Party of Albania made contact with members of the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon, UPC, Abel Kingue and Ndeh Ntumazah. To support their fight against the neo-colonial regime in Cameroon, the Albanians hosted Ntumazah’s children and wife in 1964.

Three years later, in 1967, Albania became the permanent residence of the children of Elise Osendé, who was most likely Osendé’s wife Afana. Afana, also from the UPC, was killed in action in 1966.

The Albanian embassy in Algeria served as a point of contact with the Congolese activists. After a Cuban colleague told him about Che Guevara’s exploits in Congo, the Albanian ambassador in Algiers recommended that the government in Tirana host three Congolese students who had been expelled from Belgium for political reasons, as well as the wife and child of one of them. The students were advised to go to Albania by Jacques Grippa, the head of the Communist Party of Belgium, who planned to go there for vacation.

Several Congolese students and activists traveled to Albania in the mid-1960s. In 1966, a year after the coup that brought Mobutu to power, 15 Congolese children and one child born in Uganda arrived in Albania. Among them was the child of the revolutionary activist, Willem-Emmanuel Kabasu Babo.

Kabasu Babo, traveled to Tirana in 1967, with Constantin-Marie Kibëe and Thomas Mukwid. In the Albanian capital, they reached an agreement to form a Marxist-Leninist party, which was founded in the Congo, as the Communist Party of the Congo.

Babo returned to Albania in 1970, investigating the conditions of Congolese children, and asked the Albanian government for financial and logistical support, in exchange for diamonds, gold, uranium, mercury and cocaine. The government rejected the request as Babo had been expelled from his party for alleged pro-Soviet leanings.

The Congolese and Cameroonian children were between the ages of 2 and 15 when they arrived in Albania. They grew up without their parents, some of whom were killed in the fighting.

Until the mid-1970s, Albanian authorities paid little attention to them, but interest grew, when most were in their teens and some began to show subversive tendencies.

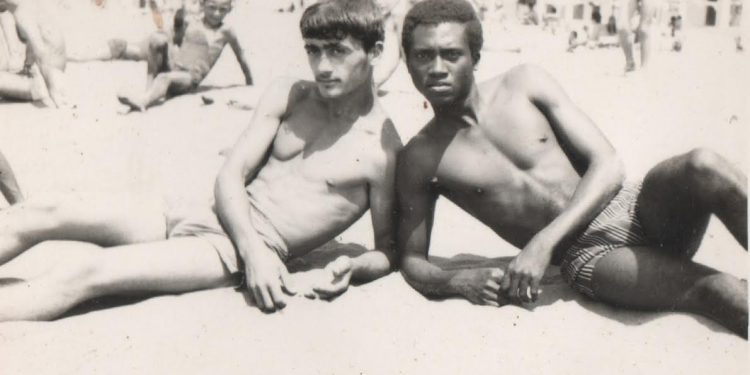

In the years 1974-’75, the local leaders of the Party Committee of the district of Vlora, complained about the “unpleasant behavior” on the Adriatic coast, of the young “Congolese” José (“Zhose” or “Zhozef” in the Albanian archives) Makanga and Vitali Pakasa, aged 15 and 16 respectively.

The Congolese pair was accused of dropping out of school, hanging out with “degenerate elements” among “our youth” and being violent and abusive. It was also said that; they were following western fashion and music.

Archival documents contain traces of the ongoing politics of marginalization. In one letter, the racist term “black” is frequently used by them when referring to Pakasa and Makanga.

According to the communist leaders of the Vlora District Party Committee, the two young men should have been put to work, like all other immigrants, or expelled from the country. The Congolese pair rejected the accusations; Makanga protested their ill-treatment and both asked the local authorities to either send them back to Congo or put them in prison.

Makanga’s emotional state deteriorated to the point where he cut his veins with a piece of glass. He wrote to the communist leader Enver Hoxha to denounce his treatment by the Albanian authorities, but the letter is surprisingly missing from the Albanian archives.

In 1978, a report by the Ministry of Culture admitted that the local authorities had marginalized the Congolese children, saying that they had come to Albania at a very young age, but were treated as foreigners and felt it.

African teenagers had a similar experience in Elbasan. In April 1975, local communist authorities complained of inappropriate behavior by Joseph (“Zhozef” in the archives) Osendé, son of Elise Osendé, and Jean Mate (“Zhan Mate/Mat” in the archives).

Both had praised the Soviet Union. Osendé, who used to live there, claimed that young people had more opportunities for entertainment. Osendé dropped out of school and spent his time reading novels, playing table tennis and listening to music on the radio.

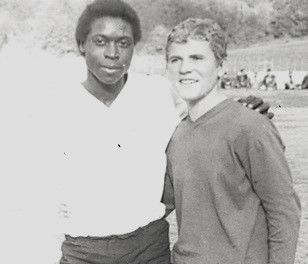

The local authorities recommended that the “African” students leave because they were “undesirable”. Moneng Charles (“Mon Eng Sharl” in the archives), an older student, attracted the attention of the Albanian authorities in 1976.

According to the Home Office, Charles spread revisionist literature and propagated decadent Western music and lifestyles. He had committed “immoral” acts with many Albanian and foreign girls and had relations with the staff of the Polish and Bulgarian embassies, the ministry claimed.

Charles was deported from Albania on January 27, 1977, when he still needed two and a half months to graduate in medicine. Before boarding the plane, Charles gave the agents accompanying him a tape with a message for Hoxha.

Appearing to speak on behalf of all Congolese students, Charles rejected the accusations against him, but said he would be grateful to Albania. He also mentioned that he often felt alone in the country and asked the party to take care of other Congolese because they could achieve more than him.

Limited impact on international relations

The spread of communist movements and the end of colonial regimes created forms of solidarity that challenged the racist ideology that characterized relations between Europeans and Africans.

However, the effects of the communist movements were limited at the level of foreign and international relations. They did not touch the intimate structures of socialist society, where foreigners and some minority groups continued to be marginalized because of their ethnicity and race.

This shows the limits of state-driven inclusion politics and sheds light on past and present forms of solidarity between Albanian and African citizens that go beyond institutionalized spaces and relationships. Memorie.al