By Dr. Çelo Hoxha

Part One

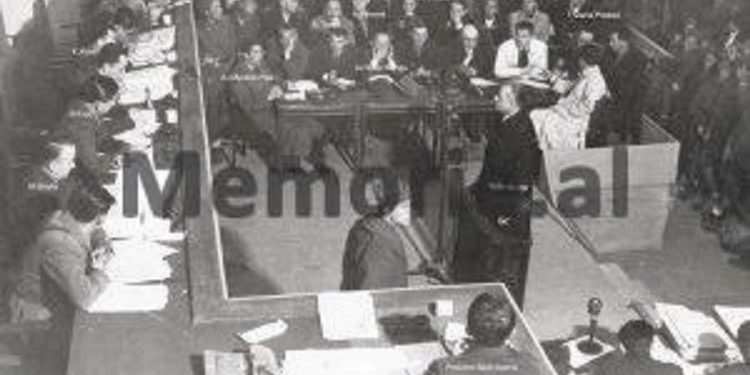

Memorie.al / In March 1945, a Yugoslav theatrical troupe arrived in Albania with a drama titled ‘The Occupation.’ It was sent to be performed in districts like Elbasan, Korçë, etc., but not in the capital. The ‘Kosova’ cinema, the only one in Tirana with a stage suitable for theater, was occupied. The ‘Special Court’ (Gjyqi Special) was taking place there. What was performed on that stage was not a drama, but a true tragedy, at the end of which 17 people were executed and 39 others ended up with long prison sentences. For the regime, the Trial was a celebration of the public lynching of 60 innocent people, most of them personalities with beneficial contributions to the history of Albania.

Why a “trial” and not a “court”?

The history of the ‘Special Court’ begins on December 15, 1944, with the decision of the Anti-Fascist National Liberation Council (KANÇ) for its creation. Article 1 of the decision states: “A Special Court shall be established in Tirana for the primary war criminals, Albanian or foreign.”

From an examination of the documents, it appears that the members of the court themselves were confused by the fact that KANÇ ordered the creation of a Trial (Gjyq) and not a Court (Gjykata). In the header of the Trial’s minutes, it is written: “Democratic Government of Albania / Special Court for the trial of the primary war criminals and enemies of the people, Tirana.” However, in the header of the court’s verdict, it is written: “Democratic Government of Albania / Special Court of Tirana.”

As we know, a court is, and has always been, an institution (a structure of laws and people), while a trial is a process that occurs within a court. Furthermore, another important distinction between these two concepts is: a Court implies an institution of justice, whereas a trial implies primarily a process of punishment.

The mindset that led to the creation of the court prioritized punishment over justice. Based on its documents, the ‘Special Court’ had nothing to do with justice. It was a partisan trial which, instead of the mountains, took place in the heart of Tirana and Albanian civilization. The message conveyed by the wording of Article 1 of Decision 26 is: “Arrest some people, try them, and execute them or put them in prison.”

This decision by KANÇ does not differ much from the decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Albania on March 24, 1944, regarding the trial of a partisan commander whom the leadership wished to get rid of: “You must arrest Tele Baçi, give him a trial, and shoot him.”

The Central Committee was not interested in the process, but in its end—the killing of the person. The difference between partisan trials and assassinations is that trials involve more people in the killing. At the time of the ‘Special Court,’ KANÇ and the Central Committee of the APS had almost the same composition they had in March 1944.

Outside the Legal Framework

At the time the Special Court was created, communist Albania had no law on war crimes, but according to Decision 26, “the criteria for war criminals, their sentencing, and procedures shall be based on the regulation for military courts.” The law does not define what this regulation was: by date, number, or the body that had approved it. In the archives, several regulations can be found that circulated in the hands of partisan commands during the war (translations from the Yugoslav communist army).

These regulations, or the one mentioned in the decision, are important only for the fact that, by examining the Trial documents, we discover that the legal basis was not the “regulation” mentioned in the decision, but: “Law on the organization and functioning of military courts,” No. 41, published in the Official Gazette on January 23, 1945. Nevertheless, the ‘Special Court’ remained faithful neither to the duty assigned by Decision No. 26 for its creation nor to Law No. 41.

The ‘Special Court’ tried 60 people. Of them, 24 were convicted as war criminals – 17 to death and 7 to various prison terms. All other defendants were convicted on the charge of “enemy of the people,” which was not within the jurisdiction of the ‘Special Court.’ Its task was clearly defined: to try the primary war criminals, Albanian or foreign. Those considered “enemies of the people” could have been tried by another court.

In the Indictment, the Prosecutor stated that the crimes of which the defendants were accused were provided for in Articles 14 and 15 of Law No. 41. If the ‘Special Court’ had been interested in applying the law and delivering justice, it should not have considered the charges based on Article 15 for trial, because that article represented criminals called “enemies of the people.”

With the content of the Prosecutor’s Final Plea (Pretenca), things were easier. It had a mountain of accusations against people who at that moment were in emigration or had died during the War, but it contained no legal references. Out of the 60 defendants, very few were mentioned in the Final Plea. More than a professional document, it was a vulgar political speech.

In the decision of the Special Court, there are also ridiculous articulations at unimaginable levels, but unfortunately, the consequences were severe: many fates were destroyed and many human dramas were caused. According to the decision, the court formulated the sentence for 13 of the defendants as follows: “For war criminals or enemies of the people… from 30 years of prison and forced labor” or “from 15 years of prison and forced labor”!

After a month and a half of trial, the ‘Special Court’ had not been able to determine what kind of crimes the defendants in question had committed – to declare them as “war criminals,” or as “enemies of the people,” or both together. Undoubtedly, the court’s hesitation shows that they were neither one nor the other, but were entirely innocent. I am listing these 13 people: Sokrat Dodbiba, Mihal Zallari, Etëhem Cara, Ndoc Naraçi, Andon Kozmaçi, Lazër Radi, Sami Koka, Sulejman Vuçiterni, Gjergj Bubani, Rrol Kolaj, Bilal Nivica, Ismet Kryeziu, Jakov Milaj.

The ‘Special Court’ issued 19 death sentences and executed 17 of them. What happened to the other two? This same Court, in the same decision, removed this measure from two of those sentenced to death – Qemal Vrioni and Tefik Mborja – and sentenced them to prison. The Court argued this decision as follows: “Qemal Vrioni had surrendered before the deadline set by KANÇ for the surrender of criminals, while Tefik Mborja, after the fall of Shefqet Vërlaci’s government in 1941, had withdrawn from politics, sympathized with the ‘Movement’ (the communist-led resistance), helped it,” etc.

From a human standpoint, this legal dilettantism was a good thing because it saved two human lives from death, but from a legal standpoint, this action is a disgrace in the history of Albanian justice institutions.

Historically, in Albania and other countries, the decisions of a court have been changed (even in the period before 1945) only by a superior court. This happened not only because the judicial system in Albania had been destroyed in 1945, but also due to the deficient legal and civic training of the people who were assigned to perform the duties of judges, prosecutors, etc.

The Special Trial – The Indictment

Law 41, Article 14, considered a war criminal to be any person or group of persons who had inspired, organized, ordered, executed, or assisted in these criminal acts: murder / torture / the shaming of women / forced displacement of populations / sending to concentration camps / sending populations to forced labor / robbery, burning, theft, destruction, looting of state and private property / those who were collaborators or aids to the terrorist apparatus and terrorist formations of the occupier / those who ordered and assisted the mobilization of the Albanian people for the enemy’s army.

In the indictment, the Prosecutor raised 11 charges against the defendants. Some of the charges, even if they had been true, did not constitute a war crime. Summarized briefly, these charges were:

- Preparation and facilitation of the occupation of Albania by the defendants (separately or jointly). It is known that the occupation was carried out by the fascist army and there were no Albanians in it, either as leaders or as simple soldiers.

- Some of the defendants had participated in the cabinets “formed by the occupier,” an action that did not constitute a war crime.

- The defendants, in cooperation with the Germans, had created the National Assembly and the Executive Committee – according to the prosecution, institutions servile to the Germans. The creation of these institutions was not a war crime. Furthermore, we can add here that the Prosecutor, by accusing some of the defendants of having come out with the slogan of “independence and neutrality,” turns out to have been against the independence of Albania, and consequently, this aligned with the interests of the occupiers.

- A portion of the defendants had cooperated in the creation of ‘Balli Kombëtar’ and ‘Legaliteti,’ which the prosecutor considers “treacherous” and “mercenary,” or had been exponents of these organizations. Based on Law 41, Article 14, these actions did not constitute war crimes.

- Another charge was that the defendants, jointly or separately, had betrayed the national liberation struggle. Treason, firstly, would have occurred only if the defendants had been part of the national liberation movement and then left it, but none of them had been part of it. However, even if they had betrayed that struggle, based on military law, this did not constitute a war crime.

- A portion of the defendants were accused as publicists, agitators, informants, and spies for the occupier. Again, the argument is the same: all these actions did not constitute war crimes.

- On the other hand, some charges that seemed to describe activities constituting a war crime – always based on Law 41, Article 14, such as participation in the military formations of the occupier, assistance in the apparatuses of terror and terrorist formations, destruction of bridges, fields, harbors as people’s property – were not proven.

The way the charges were formulated, which I will discuss further, clearly shows the falsity of the accusations and the innocence of the defendants.

In the “Kosova” cinema, there were also people with a high legal consciousness who, because based on their civic logic they had committed no crime, did not leave Albania and, unfortunately, ended up before the firing squad, because the people representing justice were a pack of ignoramuses and sycophants.

Kol Tromara was not a law graduate; he had no higher education at all, unlike the vast majority of the defendants, but when the prosecutor asked him to call Mustafa Kruja a traitor, he replied: “As for Mustafa Kruja, as long as there is no court decision, I cannot say he was a traitor.”

Bahri Omari, a graduate in administration and not law, reacted in accordance with his training when he said; “if Ismail Golemi has said that ‘Balli’ cooperated with the Germans in Gjirokastër, he must have had a written letter from the Central Committee.”

I brought only two examples just to show what the defendants’ expectations of the court were. They had the conviction that the court would judge based on documents and facts, and this was their misfortune: they had models of responsible institutions in their minds.

How Were the Charges Fabricated?

The Central Commission for the Detection of War Crimes and Criminals handed over to the ‘Special Court’ for trial the investigative materials belonging to the arrested defendants. The content of these materials – which are not found in the ‘Special Trial’ file, at least not in the one made available to me – is unknown.

However, by examining documents that speak of the functioning of the Central Commission for War Crimes and Criminals, it is clearly seen that the investigations were as amateurish and as politically motivated as the trial.

On December 22, 1944, the Central Commission sent a circular to all National Liberation Councils of the prefectures and sub-prefectures, by which it ordered the creation of investigative commissions for the detection of war crimes and criminals, Albanian or foreign.

The commissions were to consist of 9 members: 2 members of the National Liberation Council of the prefecture or sub-prefecture, one delegate of the anti-fascist women (communist), one member of the Anti-Fascist Youth, two members of the National Liberation Army, two members of the National Liberation Front, and one judge appointed by the executive committee of the prefecture or sub-prefecture.

In case a judge was not found, then his place was taken by one of the members of the local military court. This court member might not necessarily have legal training, but in most cases could even be illiterate or with only 3-4 years of schooling. The commission was headed by the judge or the person replacing him. For the conduct of investigations, it was not necessary for all members of the commission to meet together; they could work separately./Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue