From Assoc. Prof. Dr. Thanas L. Gjika

Part Four

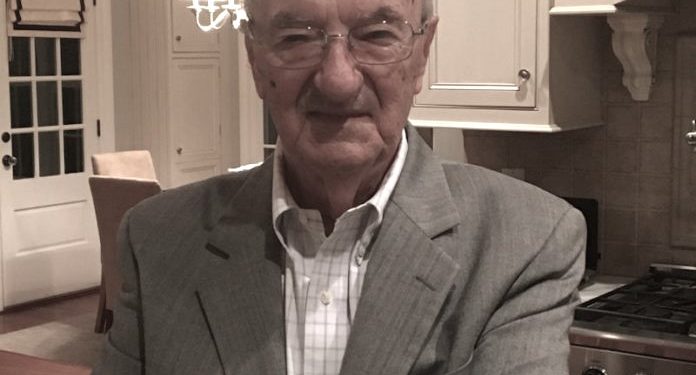

(A portrait-biography dedicated to the distinguished activist, Professor Sami Repishti)

Memorie.al / Sami Repishti is one of those who suffered greatly, and having endured torture in interrogation, the suffering of prison, the danger of escape, and persistent work to qualify and serve the homeland as anti-communists, they deserve to be called heroes of the Albanian world while still alive. Along with Arshi Pipa and Martin Camaj, he constitutes an elite trio from Shkodra, who, through their lives and work, carried forward the patriotic and intellectual mission of the National Renaissance and the patriots of the Second World War and beyond. Professor Repishti has, for more than half a century, deserved to be called an autonomous Institution through his multifaceted work in defending the rights of Albanians wherever they live, with memorandums, political articles, analyses, essays, literary creations, speeches at conferences, interviews on Radio “Voice of America” (VOA), through his work as co-founder of several patriotic organizations and associations, and with concrete actions in the homeland and in Kosovo, to closely aid the processes of democratization and the creation of a legal state.

Continued from the previous issue

Similar to the fate of the Vlora-native professor Gjonzeneli is the fate of the Shkodra-native philosophy professor, Preng Kaçinari, described in the writing ‘Nji vorr i harruem’ (A forgotten grave). This philosophy teacher at the “At Gjergj Fishta” high school in Shkodra, a rare intellect, graduated from the University of Montpelier, France. This professor, with his behavior, intelligence, and deep knowledge, had earned the respect and love of his students and the citizens of Shkodra. After the fascist occupation, he called upon his students and took to the mountains with them, fighting alongside the author against the fascist occupier.

However, he was scorned, left unemployed, and forced to die of starvation, for the sole “fault” of not joining the communist forces and because he had closely known the future dictator of Albania during his studies, whose jealousy and paranoia did not allow those more capable than himself to survive. During the hero’s final meeting with the author, he briefly formulated the essence of morality, the core of what the party-state demanded from teachers and educators: “Surrender your conscience to the devil, annihilate your personality, lose your dignity as a human, discard all basic moral principles, then you are suitable for the indoctrination required in education.”

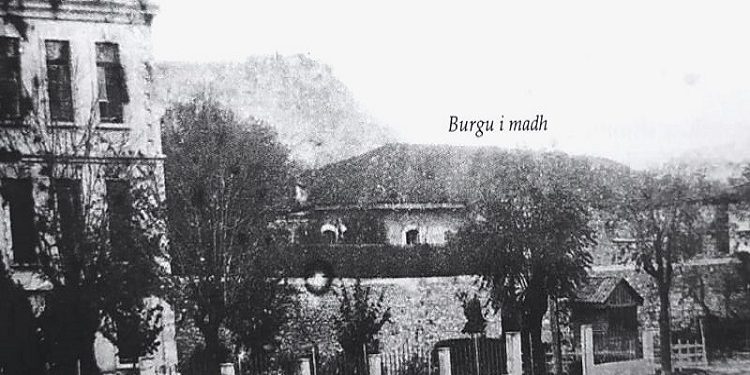

In such an oppressive situation, this pure intellectual, loyal to the principle that “for nations, as for people, honor stands higher than life,” left unemployed, with no means of livelihood, ended his life by suicide in the Tirana cemetery in 1956. Even more tragic is the fate of the Shkodra lawyer Qazim Dani, described in ‘Plaku i numrit 10’ (The Old Man of Number 10), a man who was imprisoned without the slightest cause. This imprisonment angered his 16-year-old son, Bardhosh, who, unable to bear the injustice, decided to escape along with his two friends, Ibrahim Derguti and Mark Cacaj, all three only sons. These inexperienced boys were killed by the border guards.

After leaving them to rot in the city square for several days to terrorize the youth of Shkodra, the police allowed their family and friends to bury them. Bardhosh’s mother went mad from the shock of the macabre event. When her husband was released, prematurely aged, she harshly greeted him, shouting: “You killed my son! You killed my son!” at a time when the father did not know of his son’s tragic end. Both mother and father, left in dire straits, without ration cards for bread, with three daughters who barely earned a living through the hardest manual labor, and branded with the ominous epithet “enemy of the people,” felt superfluous and withered away one after the other, waking up freezing on the balcony of their house…

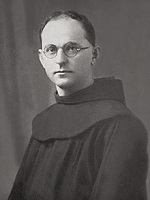

‘Bir i dejë i Shen Françeskut’ (Worthy Son of Saint Francis) is dedicated to the portrayal of the cellmate in the interrogation unit, the cleric Father Çiprian Nikaj. This devoted cleric, along with his colleagues Father Pal Dodaj, Father Mati Prendushi, and Father Bernardin Palaj, was arrested in mid-November 1946 when some rusty rifles, left behind by a German sergeant during the retreat, were found in the Franciscan Convent. Those rifles were neither used nor usable, but had remained in the Convent due to carelessness, with their handover to the police constantly being postponed.

The snitching was done by a young seminarian, recruited by the Sigurimi (Secret Police). The torture of these clerics, who were held in different cells, was intended to force them to admit that the weapons were hidden to organize a popular uprising against the regime, as was claimed by the Albanian and Yugoslav communist propaganda. To prevent the truth from being distorted, Father Çipriani confided the truth about the presence of those weapons in the Convent to the author and tasked him to testify to this truth after being released from prison. Fulfilling the testament of his cellmate is the main reason for writing this portrait.

The simplicity and spirituality of the devoted cleric Father Çipriani are conveyed through the prayer he repeated several times a day, addressing God: “Our Father in Heaven! Help me to be worthy of your grace and love!” This modest being, who appeared extremely withdrawn during his prayers, was very powerful in words and thoughts. With the advice and comfort he gave the author before and after the tortures, “he lightened my suffering with the spirit of hope and filled my heart with the spirit of resistance,” the author states, describing the severe psychological state in the darkness of the cell, where a person lost the notion of time and often the desire to live…!

The mistreatment of ordinary people is vividly depicted in the writings ‘Dukagjinasi i pafat’ (The Unlucky Man from Dukagjin), ‘Djali i Lumës dhe Bajraktari’ (The Boy from Luma and the Bajraktar). The heroes of these works are sons of the highlands of Northern Albania, honest people, anti-fascist patriots. Such are the brothers from Dukagjin, Mark and Kolë Prela, the sincere highlander Mehmet Dokuzi, and the bajraktar (chief/standard-bearer) of a remote village, Sylë Bajraktari. All these heroes, without being opponents of the regime at all, are punished by it. Mark and Kolë Prela loved the new regime, but as honest people, even though they had fought as anti-fascists alongside the partisan forces, they refused to carry out the murderous orders of the People’s Defense Brigade (the Sigurimi forces), who went through the Highlands to massacre the inhabitants there, with the sole purpose of instilling terror, fear, and absolute submission to the new “popular” regime.

The simple and sincere young man, the honest Mehmet Dokuzi from Luma, could not understand how a man could fall so low as to lie against his own villager. The Sigurimi informer, a fellow villager, had falsely claimed that Mehmet did not like the regime, that he was an “enemy of the people,” which led to his imprisonment and forced labor in the swamps of Maliq. His rhetorical question: “Si mund të bjerrë burri kaq poshtë!” (How can a man fall so low!), used as a refrain throughout the writing, reveals the injustice of many sentences and the downfall not just of some informers (spies), but of the communist regime itself. This regime, which came to power with fanfare as the “creator of the new world” and the “new man,” very quickly revealed its true dictatorial, anti-human face.

To justify the abuses and to create the idea that the “old world” it overthrew was a reactionary world, this regime, through various sentences, declared many words, and their bearers, as hostile, reactionary, and anti-popular. By force, the words ballist, bajraktar, gendarme, defense-lawyer, priest, etc., were loaded with a negative emotional content. All Ballists (members of the nationalist movement Balli Kombëtar), Bajraktars, gendarmes, defense-lawyers, priests, etc., were declared and fought against as enemies and traitors. Among these persecuted are many of the convicted people mentioned above, as well as Sylë Bajraktari, a man who could not understand why he was called an “enemy of the people, a bloodsucker of the people,” when he and his ancestors as bajraktars had strived to enforce the Kanun (traditional law) and the laws of the Mountains to maintain order in their village.

The author’s personal life full of hardship and his close acquaintance with the suffering and tragic end of the lives of these representatives of the Albanian intellectual elite prompted him to reach a very mature characterization of the era of dictatorship as early as 1960-1962, a characterization that many writers and scholars of our days have not yet achieved. For the author, that era was the epoch that killed the honest teacher that eliminated the devout cleric that rotted the intellectuals educated in Europe in prisons that squeezed the merchants through torture, that tormented the workers with hunger, and that impoverished the villagers to the extreme. An era which “defiled the student, poisoned the youth, elevated the idiot, inspired the naive. It made hatred a cult, and career the ideal.”

Co-suffering and close acquaintance with the life and death of such heroes motivated the author to find the path to salvation not in enduring the suffering, which would soon lead him to a premature death during a re-imprisonment, re-internment, or labor camp, but in escaping the homeland.

The elevation to high positions of inferior people, of those “people who served the regime with blind loyalty without any pangs of conscience,” is shown by describing how ignorant, almost illiterate people, taken from villages, were armed and put in commanding duties in prisons and labor camps, where they cruelly mistreated their own compatriots who were convicted without fault. In fact, the author dedicates no full portrait or writing to such “soulless” people, but only describes them in passing and in contrast to his cellmates, people convicted not because they had committed any fault, but because terror had to be instilled in the population.

The author makes an exception for the case of Xhevahir (Jewel), as the prisoners called Corporal Jonuz from Berati, whom he portrays within the portrait of the Bajraktar. This person stood out from the other police officers. He had woken up from the party’s drug and hated the regime’s bestial politics, striving to alleviate the suffering of the convicted as much as he could. Sometimes he would tell them who the recruits were among the convicted, and sometimes he would tell them news from life outside the prison to fill them with patience and courage…

All the writings summarized in the book ‘Pika loti’ (A Drop of a Tear) share a common artistic characteristic. The use of a very sensitive lyricism stands out in them, a description with great fidelity and with well-chosen details to characterize the heroes being portrayed. The author’s lyrical interventions, the outbursts of emotions, the meditations, and the accurate formulations for characterizing the era, increase the emotionality, credibility, and truthfulness of the writings, and especially their artistic level.

The author’s life up to his escape is treated in detail in the autobiographical volume ‘Nën Hijen e Rozafës’ (Under the Shadow of Rozafa) (ONUFRI, 2004, 344 pages), where the focus is not on the deeds and conversations of his cellmates, but on the author’s and his family members’ life, suffering, thoughts, meditations, and generalizations. The descriptions of personal and family life, simply given with literary figures through a warm narrative, create the idea for the reader that they too are living the suffering together with the author…!

From a linguistic perspective, these two literary works, as well as his works of other genres, are distinguished by lexical richness and elaborate sentences and phrases, for the literary Shkodra dialect brought closer to the common Albanian literary language. This phenomenon is rare among those who write in the Shkodra dialect, as most of them, wanting to showcase the richness of this dialect, emphasize the differences from the literary language and use as many of its sub-dialectalisms as possible.

In conclusion, we say that the works ‘Pika loti’ and ‘Nën Hijen e Rozafës’ worthily belong to the foundations of Albanian prison literature, that they precede the major works of our literature, ‘Rrno vetëm për me tregue’ (Live only to tell) by Father Zef Pllumbi and the novels of Visar Zhiti ‘Rrugët e Ferrit’ (The Roads of Hell) and ‘Ferri i çarë’ (The Torn Hell) (OMSCA-1 2012) and some of their counterparts.

Without hatred, but with law

When I asked Professor Sami what his greatest achievement was, he did not mention any work title or any of his concrete deeds, but told me: “My greatest success has been, and remains, my victory against hatred. I have never allowed myself to hate, despite the strong opposition I have shown when I did not agree. Thus, on the first day I arrived in Albania on August 9, 1992, I declared to journalists in Rinas: ‘I return to the homeland with love for everyone and with hatred for no one,’ a non-original statement, but a cornerstone for my thoughts, borrowed from President Abraham Lincoln’s speech held at the end of the Civil War in Gettysburg PA, during which more than 600,000 Americans were killed.”

Many people in Albania misunderstood, thinking that Professor Repishti had returned to the homeland to preach pacifism and that he was not thinking about punishing the crimes of communism. This persecuted man, who had experienced so much suffering from the communist dictatorship on his own back and that of his parental family members, has never been and is not against punishing the crimes of communism. What distinguishes him is the fact that he believed and believes that this process should and must be carried out by law, meaning that first, the crimes of the communist dictatorship had to be and must be legally defined, and then their punishment should be carried out according to the law.

Some of his generalizations about the state of Albania in transition are proverbial. Such are the sayings:

- “Crime has not been punished, and the criminal has returned to power dressed in the robe of the ‘European socialist’.”

- “A regime born of lies, maintained by the barrel of a gun.”

- “A society shattered by the heavy weight of crime committed by indoctrinated executioners.”

- “The political situation remains chaotic and the economic one desperate.”

Life in the USA, the higher education he completed in Italy, France, and the USA, and the scientific titles he defended, had matured the mind of this anti-communist man from Shkodra. However, the democratic rulers could not understand his maturity. Sami Repishti was against the harsh language used by the socialist media against the democratic government officials and democrats in general. He explained the socialists’ straying by linking it to their communist origin, but he could not allow the media of the Democratic Party to use the same language full of insults and abuse against opponents, the socialist opposition.

The harsh language full of insults, abuse, and slander reminded him of the former language of the Communist Party of Albania against its opponents, the Ballists and Nationalists. This language full of insults and slander was similar to the former language of class struggle. The misunderstandings between him and the leaders of the DP quickly led to the cooling of relations and Professor Repishti’s departure from Albania and his return to the USA. Sami Repishti was not heard because he was part of those political and social forces that constituted the true opposition to communism.

Such forces were predetermined by Ramiz Alia not to be included in the transition processes, let alone be consulted or lead them. Pluralist Albania with a market economy was supposed to be built and inherited by the sons and faithful servants of the former communist leadership, the majority of who continue to rule even today. The courage to demand a right, or to criticize a wrong phenomenon, has been distinguishing features of Sami Repishti. In April 1965, as shown above, he was the first to ask the American Congress to protect the rights of the Albanian people of Kosovo, even though the atmosphere was hostile. He later repeated this request in various articles and memorandums, as well as in speeches he gave several times in the American Congress and in some of his meetings at the White House.

In 1986, at a meeting with Vice President George Bush (Senior), he prepared and submitted the Petition for the opening of an American information office in Kosovo. The opening of this office, albeit with a few years delay in 1996, created favorable conditions for informing the American government about Serbian repression against the Albanian people of Kosovo. That office played the role of an American embassy in the capital of oppressed Kosovo. When Professor Repishti went to Albania to help the democratic processes in the summer of 1992, he asked the former Prime Minister Aleksandër Meksi for an explanation about the “process” of granting veteran status to the “executioners” of communism as well, a request for which he did not receive an answer.

Towards the end of 1992, after 30 years of membership in the Pan-Albanian Federation Vatra, he left it without fanfare, but determined because he saw that this patriotic organization became an instrument of the Albanian government’s politics, contrary to Article 5 of its regulations which states: “Vatra does not deal with politics.” He left because he did not receive an answer to the questions he addressed to the Federation’s leadership: “Why have we become an instrument of the Tirana government? Why is the Federation congress not held? Why are no new branches opened?” From 2017 until today, Sami Repishti has not ceased to point out that Mr. Donald Trump is not suitable for President of the USA and with his civic courage has often shown the weaknesses of this President as a politician and statesman. / Memorie.al