By Prof. Dr. Sylë Ukshini

– The Movement for the Liberation of Kosovo – part of European emancipation –

Memorie.al / The testimony of James Rubin at the Specialist Chambers have re-established a missing balance in our narrative of the Kosovo War. At the same time, it has highlighted, as Ismail Kadare would say, an “Albanian self-importance” (“Kapardisja shqiptare”), which is not only a phenomenon of our days but also appears in the crucial moments of 1999. The significance of Rubin’s testimony, as a credible third party with international standing, brings a more realistic dimension to what happened in and for Kosovo, overturning the claims of some local figures blinded by personal and tribal grudges, who revert Albanians to the clashes of past centuries.

The convergence between what Rubin states and what Kadare notes in his diary are meaningful: historical truth cannot be written without multiple sources and without a rigorous contextualization of the circumstances in which the events occurred. Consequently, the events of 1998–1999 cannot be “implanted” into today’s political rivalries without turning into a caricature.

The Testimony of James Rubin and its Weight

Rubin testifies that, at the time, the US and Great Britain had already made the strategic decision that Kosovo should secede from Serbia. This framework helps to understand why the signing of Rambouillet was not an isolated act, but a link in a broader diplomatic and military process. For the Albanian public, however, there were voices demanding the continuation of the war even without American support; this political and emotional ambivalence explains the internal tensions of that time.

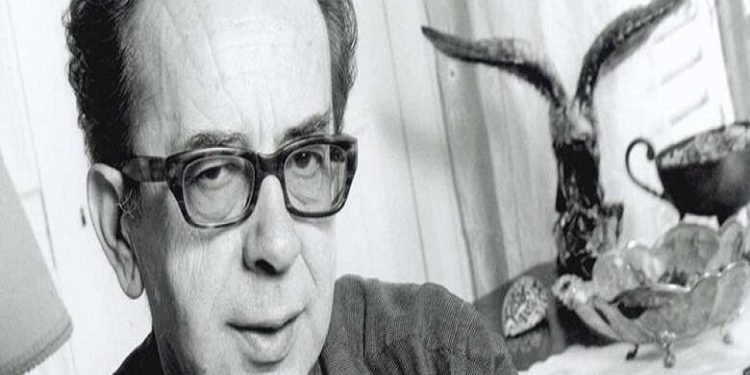

Kadare as a Witness and Moral Authority

In his essay, “This Calamity came and we Saw Each Other – Diary for Kosovo” – articles, letters – Kadare describes the late meeting on March 18, 1999, with Hashim Thaçi, the leader of the Kosovo delegation at Rambouillet. His note is of particular importance because it aligns with the factual line of Rubin’s testimony and, above all, because it positions the writer as a clear supporter of the political act at a critical moment.

Kadare’s unreserved response to publicly endorse the signing gives the text a normative dimension: he not only records an event but exerts moral weight in support of a historical decision. In this perspective, Kadare reads the act as a “good omen,” legitimizing the KLA (Kosovo Liberation Army) against the slanders of Serbian and Russian propaganda, as well as the doubts of a part of the Western press.

Rambouillet: Pressures, Responsibility, and the Need for Consensus

Kadare’s fragment highlights that the decision to sign was accompanied by multiple pressures: the criticisms of Adem Demaçi against the delegation, the risk of dissatisfaction from some KLA commanders, and the polarization of Albanian public opinion. In this context, the responsibility for the country, the war, and the KLA weighed on the shoulders of a young leader like Hashim Thaçi. The awareness of the need for broad consensus within the Albanian political spectrum is linked to the historical lesson from the earlier mistakes of Kosovar elites at key moments. Likewise, the misguided stances of 1981 contributed to the gradual weakening of Kosovo’s position, later being misused by Serbian propaganda to victimize itself and blame the victim.

“Albanian Self-Importance” and the Rebuke of a Sterile Rhetoric

At the request and encouragement of Western diplomats, Kadare publicly came out in defense of the Rambouillet process. Outraged by a rhetorical “swagger” that ignored international circumstances and strategic logic, he reacted with the article “Kapardisja shqiptare” (Albanian Self-Importance), where he noted that from “warm homes,” calls were made not to sign the document proposed by the allies, particularly by the US Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright.

“This irresponsible stance is accompanied by whims and seemingly grand gestures. One brags that he is the one who holds the decision at Rambouillet, that if he doesn’t want it, and he doesn’t go, everything must be broken. And another, who has never set foot in Kosovo, gives patriotic lessons, calling for Kosovo to be turned to ashes and dust, in the name of this or that. And so on and so forth without end. And it is always the Albanian people who pay, who suffer, who are burned and bleed. While these ‘businessmen of freedom’ never suffer anything,” Kadare wrote on February 24, 1999, in “Courrier International.”

The same line of argument appears in the letter Kadare sent to the Kosovo delegation: not to miss the historical opportunity, not to listen to the “irresponsible chest-beaters,” and to understand that making a concession when necessary is as much an act of bravery as fighting.

Conditional Support for the KLA and the Logic of Humanitarian Intervention

In an interview with the German newspaper “Tagesspiegel,” Kadare articulates a conditional support for the armament of the KLA, within the logic of humanitarian intervention: if NATO were to hesitate to engage with ground troops to avoid risks to its soldiers, then support for the side willing to take on the risk for the protection of civilians would be reasonable. In this context, arming the KLA is seen as a temporary instrument of collective self-defense, legitimized by the lack of immediate international intervention.

The Interweaving of the Diplomatic and Literary Narrative

Kadare’s note on Rambouillet is placed at a key moment: when the country was on the verge of decisions that would determine the course toward international intervention and, subsequently, toward independence. As a literary testimony with historical content, it intertwines politics, literature, and personal experience.

At the same time, this note converges with the testimonies of James Rubin in The Hague, creating a line of coherence between the cultural source and the diplomatic evidence. The combination of Rubin’s testimony and Kadare’s notes offers a complete framework for viewing Kosovo’s liberation movement as part of European emancipation. Western diplomacy, the moral authority of the writer, and the political responsibility of the Kosovar delegation create an interpretive triad that helps to understand why Rambouillet should be read not as a weak compromise, but as a necessary step towards freedom.

In this sense, the narrative of Rubin at the Hague Tribunal and Kadare’s diary complement an unchangeable historical moment and not only restore historical balance but also set the methodological standard: multiple sourcing, context, and political prudence as prerequisites for historical truth about Kosovo. In this context, here is what Kadare writes about his meeting with Hashim Thaçi:

Paris, March 18, 1999

Late in the evening, Hashim Thaçi expressed the desire to meet me. They came close to midnight, together with Ram Buja and the delegation’s interpreter, Bukurije Gjonbali. We talked tête-à-tête for a while. In the other room, my family members, Thaçi’s two companions, and the Albanian Ambassador to Paris were having coffee. French secret police guards were everywhere on the building’s stairs. Thaçi was unsettled. Naturally, he had decided to sign the agreement, but there were many pressures. In Kosovo, Adem Demaçi continued to incite dissatisfaction against the delegation, even calling them traitors. Some of the KLA commanders could create trouble again.

Thaçi mentioned the letter I addressed to the delegation in Rambouillet, as well as the article “Kapardisja shqiptare,” which I had published three days later. He says he tries to learn from every criticism, but the situation is not that simple. He asks me a question that is simultaneously a request: If he were to sign the agreement tonight, would I, as an Albanian writer, publicly support that act? Without any hesitation, I answered that yes, I would support it. Even right at that moment. The tête-à-tête conversation ended. We invite everyone into the living room. I am doubly happy. First, because this matter is being completed.

Second, because in this consultation between Kosovo’s fighters and a man of culture, I see a good omen. So many slanders have been made against the KLA: slanders from Serbian propaganda, from Russian newspapers, from a part of the Western press, and even from the Albanian ultra-pacifists themselves. But they, with this gesture, with this consultation, show that, despite the inevitable layers of a Balkan guerrilla, they still have a strong dose of idealism – a dimension that connects them to the future, to European civilization. A short time ago, in the Albanian press – in “Kosova –Press,” if I am not mistaken – I expressed the opinion that the movement for the liberation of Kosovo should be part of European emancipation. The family of the continent’s peoples must receive this message. And respond to it.

Kadare’s letter, sent to the Kosovar delegation in Rambouillet

“You are there for the freedom, therefore for the life of Kosovo, and not for its death! The entire fate of human lives, the lives of women, children, and men, depend on your wisdom, bravery, and honesty, along with the fate of Kosovo. In this case, I wanted to reiterate that to make a concession when it must be made is just as much bravery and heroism as when you are at war. Please do not listen to the irresponsible chest-beaters who find it easy to shout: either immediate independence, or let us turn to ashes! No one has the right to propose ashes and death for their own people. You are there for the freedom, therefore for the life of Kosovo, and not for its death.”

Paris, February 22, 1999

Unable to orally tell you some of my thoughts about what is happening and what the entire Albanian nation expects from you, allow me to address you with this short letter. A concern from the last hours became the impetus for this letter, especially Madeleine Albright’s declaration that:

a) if both sides do not agree, there will be no military intervention in Yugoslavia,

b) if the Albanians become the cause of failure, aid to them will be discontinued.

I believe I am capable of distinguishing between statements made for pressure reasons and those that express a deeper truth. From the reports I have and from an alarming intuition, I am convinced that the statement of the US Secretary of State must be taken with the utmost seriousness. In both cases, even if both sides, Serbian and Albanian, do not agree, and especially in the second case, if the blame falls on the Albanians, the Serbs emerge victorious. And in both cases, the Albanians emerge as losers.

Apparently, the Serbian strategy was based precisely on this trap: to make the Albanians co-responsible, even guilty, and for themselves to emerge clean. The Serbs have nothing more to ask from this conference. For them, it will be a great victory. I think this is enough to understand that the Albanian delegation should under no circumstances fall into the trap. The dramatic question posed is: although our aspiration is greater, can we nevertheless be satisfied with what we have gained? Could more have been achieved from a first transitional phase of three years? / Memorie.al

![“When the party secretary told me: ‘Why are you going to the city? Your comrades are harvesting wheat in the [voluntary] action, where the Party and Comrade Enver call them, while you wander about; they are fighting in Vietnam,’ I…”/ Reflections of the writer from Vlora.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)

![“The ensemble, led by saxophonist M. Murthi, violinist M. Tare, [with] S. Reka on accordion and piano, [and] saxophonist S. Selmani, were…”/ The unknown history of the “Dajti” orchestra during the communist regime.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/admin-ajax-3-350x250.jpg)

![“In an attempt to rescue one another, 10 workers were poisoned, but besides the brigadier, [another] 6 also died…”/ The secret document of June 11, 1979, is revealed, regarding the deaths of 6 employees at the Metallurgy Plant.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/maxresdefault-350x250.jpg)