By Isak Shema

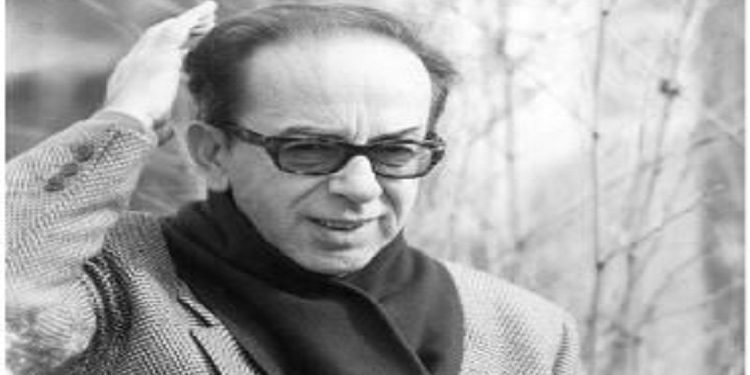

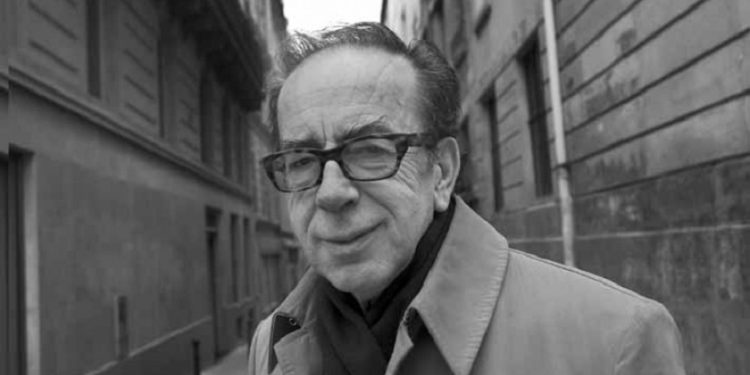

Memorie.al / The object of study of this paper is the treatment of the theme of Kosovo in the novels of Ismail Kadare, with a special focus on the image of Kosovo in the novels: “Three Elegies for Kosovo”, “The Wedding Procession Turned to Ice”, and in the novella “The Ballad of J.G.’s Death” by Ismail Kadare. The Albanian world, as well as the universe, the motifs and themes related to it, and its presence on the national and universal plane, are presented with creative and artistic dignity in the 20 volumes of the final edition of the complete works of this writer.

The theme of the Battle of Kosovo (1389) has been treated in many literary works. Different songs of popular epic poetry are dedicated to this historical event. In the book ‘Questions in Albanology’, Shaban Sinani writes about the Albanian oral tradition and the variations of these historical songs. He also mentions Anna di Lellio’s book, “The Battle of Kosovo 1989 – An Albanian Epic”. The bibliography of this paper also includes other historical epic songs dedicated to the Battle of Kosovo. Many songs dedicated to the Battle of Kosovo stand out in the Albanian historical epic, as well as in other languages. Kadare based his work on this literary treasury and found support in it during the process of creating his novel. In written Albanian literature, this theme is present in several lyric poems, narrative prose creations, and especially in the Albanian novel. Kadare’s literary work presents the image of the Kosovo of the past, but also of the contemporary one.

The first images of Kosovo are found in the poetry of the 1960s. In the poem “Përse mendohen këto male?” (Why Do These Mountains Ponder?), etc., the poet gives a broad tableau of the fate of the Albanian people throughout the centuries. In the poem “Kosova” (1966), he gives the most complete image of the country during his first flight over Kosovo by airplane. The poem opens with the verses: “Sa herë kam kaluar mbi qiellin tënd, Kosovë,/ Midis reve të tua të rënda, gjëmimeve të tua” (How many times have I flown over your sky, Kosovo,/ Amidst your heavy clouds, your thunders). He dedicates the other poem, “Atje larg në Veri” (Far away in the North) (1968), to Gjakovë.

The poem, “The Defeat of the Balkan People by the Turks in the Field of Kosovo in 1389”, created in 1975, depicts the defeat of the Balkan people in the Battle of Kosovo in the 14th century. Based on this poem, in Tirana and Paris, during the period of March 1997–March 1998, at the time of the Kosovo liberation war, he created the work “Three Elegies for Kosovo” and published it in 1998. With three stories: “The Old War”, “The Great Lady”, and “Royal Prayer”, thanks to his artistic mastery, he parabolically presents the past and the present, the liberation war of the Albanians, and the hegemonic occupation by Serbia.

The Battle of Kosovo, fought on June 28, 1389, on the Field of Kosovo, was between the invading army of the Ottoman Empire, led by Sultan Murad, on the one hand, and the joint army of the Balkan people: Serbs, Bosniaks, Romanians, and Albanians, commanded by Prince Lazar, on the other. After the bloody battle that lasted ten hours, the Ottoman army occupied the Balkan lands, to keep them under its rule for five centuries in a row.

Two rhapsodes: the Albanian, Gjorg Shkreli, and the Serb, Vlladani, sing with the lahuta (lute) songs that express the earliest hostility and rivalry between Albanians and Serbs. Gjorgu sang: “Ngrihuni shqiptarë, sllavët (serbët) po na marrin Kosovën,” (Rise up, Albanians, the Slavs (Serbs) are taking Kosovo), while Vlladani sang: “Çohuni ju serbë, shqiptarët po na e rrëmbejnë Kosovën.” (Rise up, Serbs; the Albanians are snatching Kosovo from us). The rhapsodes refuse to change their songs, or to sing a third one. Nevertheless, upon the death of the Great Lady, they sing a third variant of their song, without changing the previous message. They, “…as if numb, sang the song about her: A black fog fell, the Great Lady died… rise up, Serbs, for the Albanian took Kosovo. A black fog fell, the Great Lady died, rise up, Albanians, for the Slav fell upon Kosovo.”

In the third part, “Royal Prayer”, the narrator is the Ottoman Sultan himself, killed during the Battle of Kosovo and buried “…under the turbah and the black wick flame.” He testifies to his tragic past, but also to the continuation of the hatred between the Balkan people: “Serbs and Albanians this time, each brandishing their own sign: the Albanians the Catholic cross, the Serbs the Orthodox one.” He is informed from newspaper clippings about the war in Kosovo in 1999, about “Names of places, surprising viziers. NATO. R. Cook, Madeleine Albright. The slaughter of children in Drenica. (un massacre d`enfants a Drenica), Milošević, Mein Kampf… Now and then my name is among them: Murad I.” Even after six hundred years, alone, he sees that the quarrels and wars of the Balkan people have no end. “Their songs were as fierce as their weapons.” With unrestrained hatred, he curses and repeats the imprecation: “May you are cursed…! May your head be eaten, you savage Balkan people.”

The work “Three Elegies for Kosovo” has aroused great interest from readers and literary critics. The novel has been translated into several languages worldwide. Eric Faye, in the preface to the French edition, highly praises Kadare’s prose and chronologically links it to the events of the 1990s of the last century, namely to 1989, when the war for the liberation of Kosovo gained momentum. He writes: “…the book includes the alpha and the omega, that is, the two extreme points of the bloody war in the land of Kosovo. The tone of this book is contrary to nationalism. Nothing drives Serbs and Albanians against each other except the traces that hatred has deposited in the collective memory.”

In an interview, when asked about his support for Kosovo and its people during the last twenty years, Kadare replies: “…I defended the freedom of the Kosovar people, which I would do for all other peoples. It was not something special, the fact that I am Albanian. It was a clear cause; it was a scandal that in Europe a people still lived under colonial conditions. My reputation as a writer might have been damaged by this, as it is not easy for a writer to continue supporting the idea that Yugoslavia should be punished for the terrible oppression it had carried out in Kosovo. It is not easy for a writer, because according to clichés, writers should be against any kind of punishment, above all, bombings.”

Nevertheless, regarding his novel’s narrative in this work, Kadare states: “My narrative comes from what I call ‘Homeric objectivity’… I have tried to respect this law: to be neutral in my literary creation. All this has given me equilibrium in that difficult place. An exceedingly difficult thing.” In the novel’s preface, Eric Faye writes: “Ismail Kadare recalls this battle in his work long before the decisive year 1989, taking a tradition from the oral epic and the written Albanian one. Thus, it appears in 1975, in the form of a short poem: ‘The Defeat of the Balkan People by the Turks in the Field of Kosovo’ as well as, later, in many of his other texts. But it is the year 1997 that, by revisiting the epic tone of ‘The Rain Heralds’, Ismail Kadare ‘revises’ the pre-battle psychosis and its development, giving us this with ‘The Old War’, which is the first part of the book ‘Three Elegies for Kosovo’… There we see Serb and Albanian rhapsodes, who act as heralds of the Serb-Albanian rivalry in Kosovo, which has roots long before the fighting against the Ottoman troops began.”

Ismail Kadare’s novel was quickly translated into many languages worldwide. The voice of this author, speaking about Kosovo, was heard with extraordinary interest. Julien Gracq, a distinguished personality of modern French culture, writes: “Few contemporary books have shocked me as much as ‘Three Elegies for Kosovo’, which Ismail Kadare published in 1998, precisely when a crisis of international dimensions was once again brewing around the Field of Blackbirds…”

Regarding the reweaving of the myth in Kadare’s literature, Stephen Brown writes (Observer, February 2000): “…Kadare writes a dense, lyrical prose, enlivened by a cunning wit, sometimes accompanied by non-incendiary, ominous metaphors. These stories claim a foundation in the history of the Balkans and Medieval Europe. They are partly historical revision and partly fable. Kadare reconstructs the past in a mix of confusion and whispers, but he also wants to reweave it into a different kind-a tragedy of Europe. Kosovo unites the East of Europe with blindness towards the East and gives the region a fatality that is both a curse and a blessing.”

The literary critic, John Murray, presenting the three stories as a compositional whole of the novel, states that: “…Kadare moves in the opposite direction of chauvinistic paranoia. Instead, he views all the protagonists, including the Turks, from a tolerant perspective.” A bard deals with Kosovo. Julian Evans expresses the appreciative opinion that the work “Three Elegies for Kosovo,” “…is humane, lyrical, comic, straightforward, and moving. The dominating point in the writing of these three stories, as in his other works, is that he sends messages about freedom, mainly to write the truth, not necessarily with facts, but the human truth. In this short, objective, yet noble book, Kadare has placed Kosovo-the battle, the myth-freed from the chains of untruth.”

Jorgo Bulo, one of the distinguished scholars of traditional and contemporary Albanian literature, emphasizes the writer’s exceptional role in the development of today’s Albanian literature. “Kadare’s work,” he writes, “is a rich expression of the enrichment of universal culture with the national artistic traditions of small peoples with ancient civilization, such as the Albanian people, one of the oldest in the Balkans. From a strong connection with this soil, coming from the antiquity of the peninsula and the revitalization of its ancient mythology, Kadare’s work brings a characteristic Mediterranean aroma to European literature and enriches it with the color of an area typical for its ethnocultural distinctiveness. The philosophy, mindset, and historical and cultural traditions of the Albanians are presented in Kadare’s work as an expression of strong national identity, the vitality of his people’s spiritual culture, and as a factor of resilience and survival. A creator with high critical consciousness, Kadare has not only poetized the spiritual values of his nation but has also lashed out at anachronistic traditions, retrograde mentalities, provincial psychology, and the conventions of Albanian society’s life.”

The demonstration of students and the entire people of Kosovo for freedom and national independence in 1981 inspired Kadare to create the poem: “Terror in Kosovo”. This is where the novella “The Wedding Procession Turned to Ice” originates, which, after being published in English and French, as well as in many other languages, “…made the world reader aware of the rebellion of Kosovo students and the truth of the Prishtina massacre in March 1981.”

The real events of the time prompted the author to create the novel “The Wedding Procession Turned to Ice”. “Kadare,” writes Eric Faye, “would be inspired by the dramatic events that happened to the wife of Esad Mekuli, the ‘father’ of Albanian poetry, published in former Yugoslavia. His wife, a doctor at the Prishtina hospital, had to answer the same accusations as the book’s character, Teuta Shkreli, during the demonstrations. What is legendary: behind the Kosovar tragedy, the epic of the Kreshniks (heroes), long present in the writer’s mind (as evidence we have, for example, the poem ‘The Alps in December’, published in 1976, or the novel ‘The File on H.’), is outlined. The title of this novel is inspired by this epic song. In it, we find the motif of marriage between Slavs and Albanians. The fatal intervention of a mountain fairy (zanë)… turns the wedding procession to stone and prevents the Serbian-Albanian marriage, just as Yugoslav violence severed the love between the Albanian Shpend and the Serbian Madlenka. Shpend dies crushed by a federal army tank.”

The bloody suppression of the demonstrations, the process of political differentiation and judicial punishments, the escalation of grievances and Serbian nationalist activity, make the marriage of Shpendbresftohti (Albanian) and Mladenka Marković (Serbian) impossible. Shpend is killed by the federal army during the suppression operations. This tragedy is reminiscent of a theme in Albanian mythology and that of the work “Romeo and Juliet”. The events take place during the eighties, starting from 1981 and continuously, and include social and inter-ethnic contradictions, ideological and political struggle, and exacerbated conflicts leading to the polarization and war of the 1990s.

Some characters are imagined by the writer. “This work, the first and extremely rare testimony of the Serbian massacre… aimed to make the Albanian public, and especially the world public, aware of the terror practiced in Kosovo.” The prose was first published in the collection of stories ‘Koha e shkrimeve’ (The Time of Writings) (1986), while as a revised novel, it was published later. Its subsequent translation into many European countries shed light on the truth of the Kosovo tragedy.”

The literary work “The Wedding Procession Turned to Ice” has been analyzed in Albanian literary criticism, and especially in foreign languages, through the prism of the most distinguished works of classical and contemporary world literature. Alain Bosquet, in the review “Albania or the Lands of the Soul,” notes that this prose “…describes the turmoil in Kosovo, a Yugoslav province inhabited by Albanians. As many times before, Kadare has liked to talk about his country, both in the distant past, which allows for allegory and digressions, and the near past…” Meanwhile, the author Guy Le Clec’h places this artistic creation in a transversal line with the dramaturgy of Sophocles.

“This long novella,” he writes in “Litteratures etrangeres” (April 27, 1987), “reprises the eternal alternative illustrated by Sophocles’ tragedy, which sets Antigone against Creon, conscience and unwritten law against state reason. However, Martin Shkreli, without a doubt, appears as Ismail Kadare’s spokesperson, when he defends the idea of ending hostilities between Serbs and Albanians, risking leaving both sides dissatisfied. Let’s leave it to time to take care of wiping out the hatred, which sets them against each other even in honorary matches, in the delirious universe of ancient epics.”

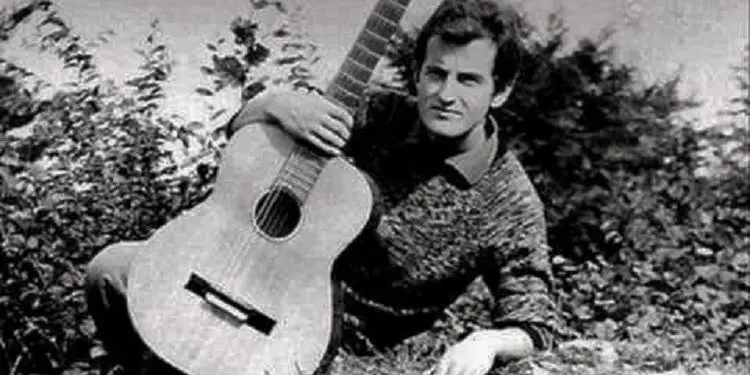

In the novella “The Ballad of J.G.’s Death,” Kadare presents the tragedy of the martyr Jusuf Gërvalla, an Albanian political emigrant who, along with Bardhosh Gërvalla and Kadri Zeka, was murdered by agents of the criminal Serbian UDB in Germany on January 17, 1982. Jusuf Gërvalla, my student, was very zealous during his university studies. For many years, he was engaged with extraordinary dedication to realizing the goal of the liberation of the Albanian people and national unification. Jusuf’s work remains a precious legacy for current and future generations.

Jeta dhe lufta (Life and War)

“Shenjat e shenjta, (The holy signs,)

Fletë testament, (A testament leaf,)

Lufta dhe arti, (War and art,)

Tutje gjithnjë akull, (Forever ice yonder,)

Këndej gjithë zjarr, (All fire hither,)

E shoh veten si Diogjeni, (I see myself as Diogenes,)

Në betejën e tmerrshme, (In the terrible battle,)

Të fjalës e të mendimit.” (Of the word and of thought.)

The cruel murder of Jusuf Gërvalla and two activists of the patriotic ideal saddened all Albanians. The writer presents the pain and revolt in the literary work, analyzes the facts, and aims to truthfully illuminate the circumstances of the human and national tragedy.

In this overview, we include a fragment of the prose:

XII

“J.G., an Albanian political emigrant who fled from Yugoslavia, with German citizenship, a journalist, poet, and musician, died on January 17, 1982, at 3:15 AM, during the operation. This was the note for his end in the Untergruppenbach hospital book. The police never managed to discover the killer. The accusations of his wife against the doctor Vidič, although formulated by a renowned lawyer, were not considered due to lack of evidence. Dr. Vidič left Untergruppenbach the very next day, on a cold day similar to the day he had arrived. Except that unlike his arrival, his departure was not recorded in any document, protocol, or protocol appendix. There was some talk about him for a while in different circles, but what was said was generally folklore. Various delusions of patients in psychiatric hospitals, remorse, murders of conscience, etc., were given as his several times, but this was never confirmed. J.G. was buried in the Stuttgart cemetery.

While searching for the most meaningful text to engrave on his grave, his family and well-wishers listened to the discs with songs and ballads that he had written, composed, and sung himself, most of them accompanied by a guitar. Listening in silence, they agreed that most of these texts were suitable for engraving on the marble of the grave. This was so clearly evident that one day, on one of those days when laughter and humor finally regained the right to be accepted in conversations about the memory of the departed, as if to make the pain even more brilliant, one of his friends said that they were right to accuse J. of having prepared his own murder. The inscription text was finally chosen from one of his ballads, but the cemetery director insisted on a change. It was the cutting, or to use a more contemporary word, the censorship of J.G., the last one in a life that had seen several such interventions, including his death, which after all was nothing but a cutting.”

“The values of his work are abundant and manifold, just as the work itself is abundant and manifold. In the entirety of Albanian literature, and in the true literary sense, it is the richest, the greatest, and the most important. Innovative in poetry, in prose, especially in the novel, and often above its general level, it has elevated Albanian literature to the highest steps, sometimes equal to other European and world literatures.”

The unique image of Kosovo in Ismail Kadare’s novels is that of a humanist creator. His work encompasses many aspects of Albanian and world civilization. His message in literature is peace-loving and dedicated to the freedom of the Albanian people, but also of all humanity. Ismail Kadare wonderfully highlights the image and artistic message for Kosovo in his modern prose. Such a message is also presented in the figurative artistic work: “Peace in Kosovo,” by the famous painter, Ibrahim Kodra. Ismail Kadare is a distinguished writer of Albanian literature with worldwide fame. With his literary opus, which has high artistic value, he also presents the image of Kosovo. His literary contribution dedicated to Kosovo is highly valued.

Thanks to the translation of his literary works into many languages worldwide, as well as his entire activity as a rare personality of contemporary Albanian and European culture, he occupies a deserved place in the history of contemporary literature. For his literary activity of high artistic value and for the extraordinary merits he has given in the field of literature, he has won many recognitions and literary awards. He is a serious and deserving candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature. / Memorie.al