By Dr. Nikol Loka

The fifth part

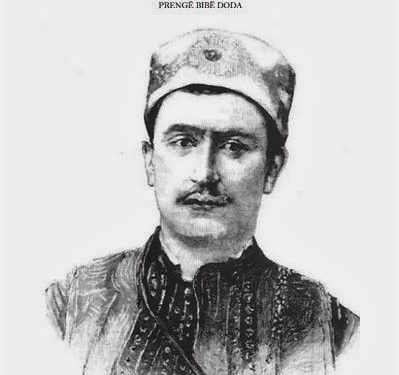

“PRENGA BIBE DODA, THE SHADOWS OF A CITIZENSHIP”

Memorie.al / The newest book “Prengë Bibë Doda, a phenomenon in Albanian political life”, by the researcher Nikollë Loka, not only expands the field of historical studies on Mirdita, the Door of Gjonmarkaj and the figure of the Mirdita Prince, Prengë Bibë Doda, but it is also a contribution to national historiography. The very rich archival material, the literature used or consulted, oral traditions, etc., make this book a real study treasure, giving the science of history a scientific monograph that enriches our knowledge of Mirdita, its captains, tradition, history etc. To study such an important and complex figure, as the figure of Prengë Biba Doda, is a high scientific responsibility that not everyone undertakes. Nikollë Loka, has done a great job of research and treatment by the professional researcher, giving us the portrait of the Prince and the general Mirditor, with the true contours. Dr. Loka has adhered to the end of the space and time, in which the multidimensional events and their protagonists have developed.

THE MONOGRAPH “ABOUT BIBË DODA, A PHENOMENON IN ALBANIAN POLITICAL LIFE”, A VALUABLE SCIENTIFIC STUDY THAT ENRICHS THE FUND OF OUR HISTORICAL STUDIES

(By Mr. Sc. Murat Ajvazi, March 2017, Switzerland)

Continues from last issue

The Gjomarks of the “eighty ships” became Captains; the “fifty ships” were compensated with the First Elder. So in Orosh, the pariah is moved by the need to maintain social balance. When Dera e Gegë Doda was given the function of Head (Kefalia) which is also called Vojvode, he certainly received the right of leadership in Orosh. It seems that the choice of the Gegedodaj, of the Marpepaj tribe, as Qefali instead of the Gjomarkaj of the Markolaj tribe, who became Captains, was an agreement between the two parties.

The door of Gegë Doda remained a rival of Kapidani and was considered a good house, but it failed to influence Mirdita in any way, since in exchange for posts, it was unconditionally put at the service of the Ottoman authorities, of the Vilayet of Shkodra.

The Markolaj brotherhood, early on, was divided into a family of elders of the tribe, the shpia of Bush, and into two families of elders: the shpia of Luli and Mar Pëndreca, who later received the title of Bajraktar and entered the great leaders of Mirdita. (67) Nowadays, the Markolajts are located in Grykë Orosh, Bulshar and Ndrshene, while the Gjonmarkaj branch of this tribe is also spread in Lower Orosh: Ndreffushaz, Qafë Molë and Livadhez. With the free movement after the nineties, Markolajt have spread too many settlements inside and outside the Motherland.

ORIGIN OF THE GJONMARKAI

The Gjonmarks of Mirdita, like any other noble family, have been interested in taking their ancestry as far back as possible and connected to important noble families. Meanwhile, there are other legends that prove that this family became important in the 17th century, when they also appear in historical sources. It is a time when history meets oral tradition, which gains credibility through historical sources. Among the oral traditions, researchers are inclined to believe those that are verified through historical documents.

Of interest for the origin of Gjonmarkaj, is an article by Pashko Vasa, once secretary of Bibë Doda:

“Gega Llesh, Gega Dodë, Gega Tanush and another Gega, whose name I remember, left the mountains of Pashtriku, without living and dying, to go and settle in Mirdita.

This document, which belonged to the great-grandfathers of the mayor of Mirdita, Bibë Dodë Pasha, was in his possession, who, before he died, had shown it to us and had sung (read) it to us, and we are sure that his son , Prengë Pasha, he must still have it in hand” (68).

From what he writes, it seems that Pashko Vasa had seen that document only once. For his part, Kapidan Biba, who decides to make that document known, trusts him that otherwise; there was no need to make it known to other people. According to this document in question (if we believe Pashko Vasa), Gjonmarkaj belong to the aristocracy of merit. They were formed as a big family, in the span of two and a half centuries.

Historical documents help us with the thesis that Gjonmarkaj did not inherit power, that is, they were not at the peak of power and strength at the beginning of the time, but they formed themselves and gradually became stronger. If we follow their rise, it turns out that initially, they were not even the first of Oroshi. In Orosh, Qemoti, as the first elder, was the house of Qefalia. (69)

In 1602, in the Assembly of Dukagjin, which is thought to have been held at the Church of Shllezhdër in Nënšejt of Oroshi, Gjon Qefalia, who is very likely the first of Oroshi, signed among other leaders. In 1648, Bibë Gjoci (70), also from Orosha, was captured by the insurgent forces of Orosha.

It is not known when, the house of Qefalia, had lost the right of pariah in Orosh?! It is only known that 130 years later, in historical sources, such as the Kefali of Orosh, that house is no longer mentioned (which now belongs to the second tribes in Orosh), but Marka Kolë Gjoka, of Markolaj. It is precisely Marku, who first received the title of Capitan. (71)

Since that time, the Door of the Capitans is widely reflected in the historical documents of the time and we see that over the years, thanks to the strength of the weapons of the Mirditas and their ability to lead in war and make politics, it is always on the rise , to culminate with Prengë Bibë Doda, who managed to be an official candidate for the Royal Throne of Albania and Deputy Prime Minister.

What about Gjonmarkaj, what were they in relation to the other inhabitants of Oroshi, one of them, or come to rule? “In the tribes of Oroshi, Markolajt are the first tribe. Gjonmarkaj and Permarkaj belong to this tribe. (72)

Similarly, in Markolaj, the house of Bush and the house of Luli enter. (73)

The treatment of oral traditions in the light of historical data, or the way people behave today with these oral traditions, is a valuable source, to discover parts of the truth not yet documented. In fact, according to legends, all the tribes of Oroshi are descended from Pashtriku. Like all the other tribes, the Markolajt, where the belly of the Gjonmarkaj enters, are from there and there is nothing wrong with us here. We have read many articles by different authors, who are bothered by the idea of population movement from one place to another. It is known from history that after the death of Gjergj Kastriot-Skënderbeu, for two hundred years in a row, in Dukagjin and especially in the territories belonging to today’s Mirdita, there were wars and people moved from one place to another to escape their horrors.

It is not a little, but two hundred years of continuous war, which had its cost. People have fled and come as the case may be, they left for a short time, until the danger passed, but it happened that they got used to the new environment and never came back. Meanwhile, other families who fled from somewhere else, they also initially settled for a short time in the territories of today’s Mirdita and may have remained here forever.

Thus, during this two-hundred-year period of existence under conditions of exterminating wars, there has been a mixing of populations. The villages were created more like territorial communities, where in addition to brother tribes; there are also tribes that marry each other. Those families that had a common origin have preserved the feeling of closeness and have not married among themselves. This is what happened with the tribes of Oroshi, where the Markolajt, and also the Gjonmarkajt, as part of them, are friends with the other tribes and neither neither give nor take. According to the residents themselves, they are autochthonous Oroshas, as much as other Oroshas.

Another legend brought by Zef M. Harapi. This becomes more serious, as it mentions tribal names, which are known to people. He also brings the origin of Gjonmarkaj from Pashtrik of Has, where according to him, Gjonmarkaj have their own tribe, with members who have come and gone. It is possible that these two legends can be summed up in a single one, since they are united by the same place of origin, – Pashtriku i Has.

Zef M. Harapi, writes: “It is said that the first of the Gjonmarkaj tribe fled from Pashtrik of Has, 6 hours away from Prizren, a place full of forest, I found this to be a blessing, I started and was rewarded for bravery… in Pashtrik , Gjonmarkaj have their own tribe called Marosh, it is a wealthy family, all Mohammedans. Amongst that tribe, they have recently, at the Gjonmarkaj’s island in Orosh, who ambushed them and shot them as tribesmen, the Gjomarkaj also stayed for three days at the Marosh Island, but what about Sherif Maroshi, how can they own blood, in 1921” (74).

In the meantime, there is another thesis that calls the Gjonmarkajs, as an old noble family, descended from Pal Dukagjin. This myth of their origin, the Gjonmarkajs, have spread wherever they could and it must be said that this thesis of theirs has been welcomed and propagated, without going into a detailed analysis to know exactly, are the Gjonmarkajs really the Dukes?! A careful analysis of the Gjonmarkas myth, about the Dukagjins, shows that we do not have a match between the mouthpiece and the facts.

Let’s see what Mark Marleku, the much-quoted author on the origin of Gjonmarkaj, writes to us. According to Marlek, who interviewed Ndue Gjonmarkaj in New York, Gjonmarkaj’s origin is from the Dukagjin family, precisely from Pal Dukagjini. Mark Kolë Pali, took place in Orosh. He had a son John (John Mark Kolë Palin). According to him, Kolë Pali of Dukagjin was exiled from Venice to Padua, Italy. Here is how it is treated at length: John Mark I (John Mark Kolë Pali), is the person who gives the name to the Gate of Gjonmarkaj.

“Turikija did not reach you, I subjugated Mirdita by force, I was healed by making an agreement with John Mark I, year (1468). The agreement is summarized in these points:

Turkey is condemned so that Mirdita recognizes only the nominal authority of the Sultan.

Mirdita has the right to legal, civil and religious freedom.

Mirdita is exempt from any state tax, does not pay any taxes or taxes.

Mirdita is regulated according to the Canon, its natural and traditional law, exercised by the chiefs of the country and implemented by Gjonmark, who is recognized as the highest authority of the Canon.

Mirdita will provide volunteer soldiers in time of war, for a time to be determined. This army will be led by the traditional leaders of the country and will be commanded by the Captain, or to his own Prince. Mirdita’s army will go to war in the national costume. (75)

Not the genealogy, but some canonical rights, proves that the Gjonmarkajs come as an aristocratic family of Treva after the Dukagjins. Even Gjonmarkaj was formed as a ruling Door, in a part of the territory of the former Principality of Dukagjin. Like the Dukagjins and the Gjonmarkajs, they stood out on the battlefield as good commanders and sacrificed a lot to protect the obligations arising from the agreement on the immunities of Mirdita. On the other hand, the Gjonmarkaj are the interpreters of the Canon of Lekë Dukagjin, which has given them a moral authority, in all the territories where this Canon is applied, which coincides with the territories of the former Dukagjin Principality.

As another proof of Gjonmarkaj’s descent from Dukagjin, a cross is mentioned, where it is marked; “Pal Dukagjini, was a prince of the town called Dukagjin. He ruled from 1444 until 1458”. (76)

The presence of the cross donated by Pal Dukagjini is not enough to prove that he was a resident of Oroshi, it may or may not be. It is known for sure that he is a member of the family that also had Oroshi in its possessions.

Marleku, writes that; “Marka Kolë Pali (Dukagjini) settled in Orosh and his son John, or as John Mark I is called, made an agreement with the Turks in 1468…”! But this year is the year of the death of Gjergj Kastriot-Skënderbeu and Lekë Dukagjini for another 11 years, kept Arbëria unconquered, until 1479. In no Ottoman document, or other documents of the time, is there any mention of agreement made between one of the Arber princes and the Turks, until 1468.

Also, if we take the points of the agreement that the High Porte made with John Mark I, the first point is not correct, because Mirdita was not only obliged to recognize the nominal authority of the Sultan, but also The Vali of Shkodra, who initially had the right to communicate orders to the Captain and in a second phase, the Captain was appointed by him as Kajmekam, making the function of the Head of Mirdita, more accepted for the administrative structures of the Ottoman state. The matter went so far that the Mirditas did not object to their Captain being called Kajmekam, but demanded that the two functions coincide, that is, the hereditary Captain was officially recognized as the first. Similarly, Mirdita was forced to pay a tax of 100 parts per head (which was never washed, but was written among the records of the Empire). (77)

It is true that the Mirditas had freedom in their own country to manage their own affairs according to their customary law, but they, like all non-Muslims, were second-class citizens and enjoyed the status of Christian populations, with some rights, which they had acquired due to the agreements with the High Gate.

It is known that the Dukagjin family had their coat of arms, with a single-headed white eagle. (78)

While Gjonmarkaj, they have two proud vultures with rays that come out of the eagle’s body and spread in all directions. (79)

In this case, we have no inheritance of the coat of arms of the princely family, from Dukagjini to Gjonmarkaj. It is known that the coat of arms is an important element of nobility and an important sign of identity. It is that coat of arms that materializes the origin and continuity of a noble door. Regardless of the circumstances that could arise even in the conditions of conflict with the Turkish authorities, or in agreement with them, Gjonmarkaj could keep the coat of arms of their ancestors.

But it must be admitted that, when a branch of a prominent family continued its splendour, it tended to identify itself differently from nearby families, and to do so, created a new coat of arms. Gjonmarkaj, did not inherit documents from Dukagjin, when it is a known fact that; princes Dukagjin; they had a chancellery, from where written documents, agreements, treaties, etc. came out. A cross of Pal Dukagjin, says very little to claim descent from him.

If the Gjonmarkaj were Dukagjin, they would not have had to change their surname, as long as they entered the bosom of a free and rebellious area, which was defended with the strength of its own weapons.

We remember that Nikolle Mejkashi hid for several years in the territories of today’s Mirdita, without changing his name, and the Turks could not capture him. But even if the name had really been changed, to hidden from the Turks, after the agreement with them, there would be no reason not to announce themselves, as they really were “Dukagjin Princes”, not content with the title “Captain”, when they were “Prince”. The title, actually the rank of “Captain”, was usually given to commanders of small military units in Christian Europe. In Mirdita, the importance of this rank increased a lot and it indicated a great commander, chief, or head of the province.

If you look at the process of expanding the rule of Gjonmarkaj, it turns out that it did not come as a result of their reclaiming the right to rule over those territories that they once “had”, but it was done mainly through wars. In the first agreement made with the Turkish authorities, or even later, Gjonmarkaj did not officially ask for rule outside of Mirdita, Trebajraksha.

The expansion to five bajraks, eight and then twelve bajraks, has been done gradually in an evolution that has lasted in time from Gjon Marku to Prengë Bibë Doda. Outside the sphere of rule of Gjonmarkaj, there remained quite significant territories of the Principality of Dukagjin, with a predominantly Catholic population, such as the Highlands of Shkodra and Puka.

The leaders of these highlands, neither sooner nor later, did not join Mirdita, despite the fact that they looked at her with sympathy and their decisions, they wanted to match the decisions of the Mirditas. Even Prengë Bibë Doda, in 1903, when he was exiled in Turkey and was thinking of gaining the support of the highlanders, connected with Albert Gjika, who would influence the leaders of Hoti, Gruda, Kelmendi and Kastrati, that the Albanians, t They packed their weapons as soon as the first oath was given. This showed that the influence of Prenga in these highlands was not great. Memorie.al

The next issue follows

- Luigj Martini, Bibë Doda… p. 39

- Pashko Vasa, The truth about Albania and the Albanians p. 87

- Das Land der Mirditen in Daus Ausland, Wien 1890. p.450

- Pal Doçi, Mirdita, the hearth of the anti-Ottoman resistance: ethnological and historical perspective, “Mirdita” publishing house, Tirana 1999, p.131

- Simon Prendi, History: Middle Ages, Modern and Today, in Mirdita, knowledge of the birthplace, AEDP, “Mirdita” Publishing House, Tirana 1999, p.59

- Nikollë Doda, Prengë Marka Prenga, Bajraktari i Oroshi, “Mirdita” publishing house, Tirana 1998, p.58

- “Shejzat” magazine, No. XVII, year 1973, p.58-61

- Zef Marka Harapi, Mirdita in history and gojdhana until 1929, Hylli i Drita, No.1, year 1931, p.41

- Mark Marleku, Principality of Mirdita, Dera e Gjomarkajve-Kapidani, Pristina 1999, p.1976. “Shejzat” magazine, No. XVII, year 1973, p.145

- Ndoc Nikaj, Memories of a past life, “Plejad” publications, Tirana 2003, p.23

- Theodor Ippen, Old Albania, Tirana 2002, p.201

- Zef Përgega, Sarajet, no publishing house, Detroit 2008, p.43