Dashnor Kaloçi

Part one

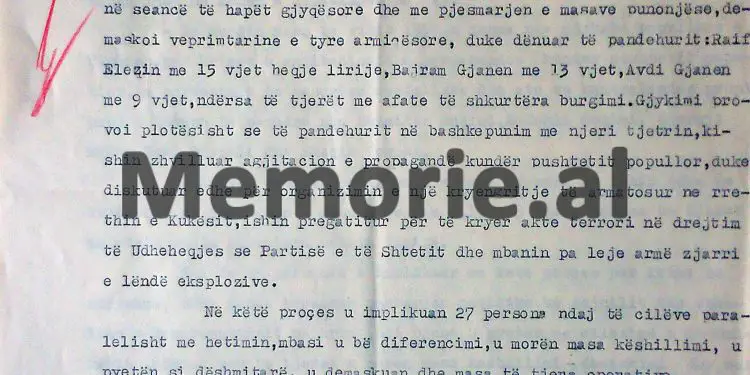

Memorie.al publishes the unknown story of three teachers from the village of Bicaj in the district of Kukës, Avdi, Shefqet and Xhevat Gjana, cousins to each other, who in the early 60’s when they served as teachers in the remote villages of that area, began to talk about the extremely difficult economic situation and the extreme backwardness in which is that mountainous province where they were appointed after studies, suffering a great disappointment since the first steps of their lives. Xhevat Gjana’s rare testimony about political conversations with his cousins: Avdi, Shefqet and Bajram Gjana, as well as with Shemsi Domin and Muharrem Selmani, who after much discussion, decided to take concrete action against the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, planned three variants: where the first was for a quick attack on Radio Kukes, from where the people would then call for an armed uprising to overthrow the popular power, the second to organize volunteer detachments for a revolt during the period of scurries throughout the district, attacking state institutions and offices with weapons, and the third for a possible assassination attempt on Enver Hoxha, which would destabilize the situation by causing turmoil. Expansion of the group with the radiologist of the Kukës hospital, Raif Elezi and the poet Hafi Nela who served as a teacher in the village of Topojan, who were ready to start concrete actions, but their conversations were revealed by the State Security and they arrested in 1970 and tried in the city of Kukes, sentenced to severe imprisonment for terrorist acts.

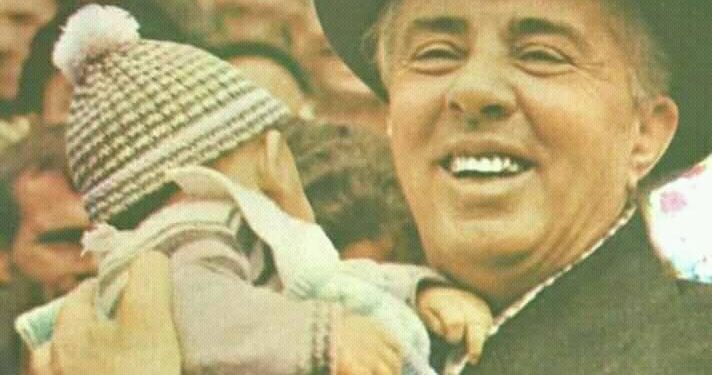

“Apart from the option of taking Radio Kukës by means of an armed attack and issuing a call through it, another way we had thought of overthrowing the government was to organize an armed revolt, with by trusted and chosen people, in the volunteer detachments during the development of the slopes, extending it to all areas of the Kukës district, of which we were acquainted. I personally talked about this with Havzi Nela (the dissident poet who was hanged on a rope in 1988, in the middle of the town of Kukës), while we were both teachers in the village of Topojan. Havziu welcomed my proposal very well and was ready for further action. While the third and last variant that we had thought could bring about the overthrow of the communist regime, was that of the assassination of Enver Hoxha, by means of an assassination, which would automatically bring destabilization of the political situation and change the course of events in Albania”. The man who speaks and testifies for Memorie.al, is Xhevat Gjana, originally from the village of Bicaj in Kukës, who tells the story that happened to him in the mid-60s, when he served as a mathematics teacher in the villages of Kukës, an event which changed the course of his life and crashed for years into the prisons of the communist regime in the deep galleries of Spaç and the horrible cells of Burrel.

Mr. Xhevat, when were your first dissatisfactions with the communist regime of Enver Hoxha born?

After graduating from the Pedagogical Institute of Shkodra in 1963, I was assigned as a mathematics teacher in some remote villages of the Kukës district, where a deep economic and educational backwardness prevailed. In those villages, I served until 1967, a period of time which coincided with the beginning of the total collectivization of the peasantry. Given that miserable reality I faced as soon as I came to life, I found myself facing a great disappointment, as what I was seeing with my own eyes was quite the opposite, from the official propaganda of the ruling regime. Exactly in those years, I had the first dissatisfaction with the communist regime in power, dissatisfaction which had its origin and source in the treatment of our family by the regime in power, because my uncle, Professor Miftar Spahia, who in the first years after the war he had fled to the mountains with Muharrem Bajraktar, lived in the US and was the fourth on the list of “War Criminals” that the communist state had banned them from returning to Albania.

That bitter reality you encountered at the time you came out as a teacher; did you talk to anyone?

Regarding the difficult economic situation and the extreme backwardness in which were almost all the villages of those remote areas, where we were violating them every day, I talked to my two relatives, Shefqet and Avdi Gjana, who so as well as me, served as a teacher. Shefqeti and Avdiu were teachers in different schools, but we got together on Saturdays and Sundays to talk to each other. In all the meetings we had, each of us brought his own facts, from the miserable life we were in. Based on this, the three of us concluded that we were deceived by the propaganda, which was done in the school benches.

The conversations you had with your two relatives were in the context of ascertaining the difficult economic situation and the backwardness of the villages of the area where you were serving at that time?

As I said a little above, everything we talked about had its origin in the extremely difficult economic situation and it was at that time that the collectivization of the peasantry in the mountainous areas exploded. The three of us were against what was happening, calling that move completely impossible for the implementation of agriculture in those remote areas. But even though we were against collectivization, we were also aware that it would be done by all means, concluding that the people were submissive and could not oppose what was happening.

Did your conversations focus only on collectivization, or did you have other reservations about the system?

The problem of collectivization was the first of all our conversations, as it was very tangible, directly affecting our daily lives, but we also had many other reservations about the regime in power. Among other things, we discussed the problems of the country’s defense, calling them completely inappropriate, the large investments made in the military field, for the fortification of the country, to the deepest areas.

Did you discuss with each other analyzing how to overcome that situation, against which you had your reservations?

We thought that the only thing that could prevent collectivization was the overthrow of the communist regime in Albania.

Were you afraid that your ideas might fall on the ears of the State Security?

Of course, we were afraid and all the conversations were made by only two people, for example, me with Avdi, or I with Shefqet. Rarely could we talk to three people. But over time our group expanded and we got closer to the other cousin, Bajram Gjana, as well as Shemsi Domin and Muharrem Selmani, where we were all intellectuals with high schools.

Did your reservations about the communist regime remain only in the context of the talks, or did you go further by analyzing what could be done?

No, we did not dwell only on the findings, but went so far as to think about what each of us could do to contribute to the overthrow of that regime.

More specifically what did you think to do?

The first thing that came to our mind was that with some selected and trusted elements, to carry out an armed attack on Radio – Kukes. After we took her building, we would call on all the people to stand up and overthrow the communist regime in Albania. We would call on the people to rise up for an armed uprising, hoping for a possible military intervention from outside.

Did you talk to anyone else about the plan to take up arms against Radio Kukes?

As a start, we talked to Raif Elez, who served as a radiologist at the Kukes hospital. He not only welcomed our proposal quite well, but was very willing to act at the earliest opportunity.

Apart from the option of taking over Radio Kukes, what were the other ways you said they had in mind to act?

Another way that had crossed our minds was that of another armed revolt, by means of well-known and trusted people, that we had in the volunteer detachments, during the snowstorms that the latter held in the villages. This option, I had also discussed with the famous teacher and poet, Havzi Nela, during the time we both served as teachers in Topojan. Havziu also welcomed my proposal and was ready to help us. While the third and last option would be, the physical elimination of Enver Hoxha, through an assassination. Which would automatically destabilize the political situation in the country and, as a result, lead to the possible overthrow of that regime.

Mr. Xhevat, did you make any attempt to realize any of the three possible variants that you had in mind for the overthrow of the communist regime in Albania?

For the sake of truth, I want to say that although we were at times very enthusiastic about the three possible versions we had thought or planned to make, there were many instances that we fell into a deep pessimism, thinking of them completely impossible! This pessimism, which often overwhelmed us, had its source in the events of Hungary in 1956, when Soviet tanks violently suppressed the anti-communist revolts and we made the comparison, what could happen to us, here in Albania, if the same thing happened again. scenario. Another thing that restrained us even more in our plans, was the fear of the State Security, which had its people everywhere and we could still be deconstructed without starting to act. However, as I said above, in addition to conversations with my two relatives, Shefqet and Avdiu, I personally also talked to Havzi Nela and Raif Elez, who not only welcomed my proposals very well, but were shown also very willing, to act at the earliest opportunity, that we might be given the opportunity.

Why did you not act when they were ready?

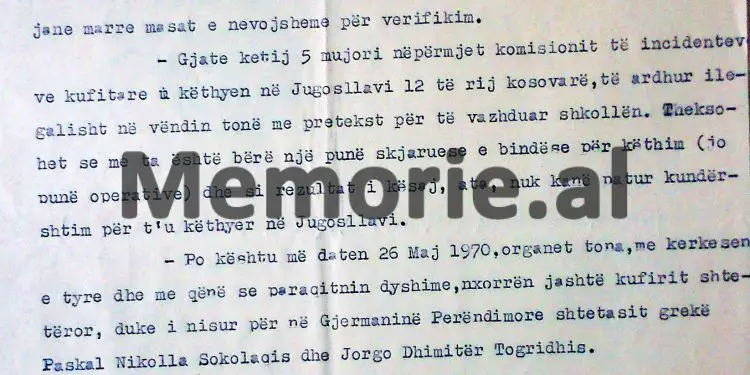

This is related to several reasons. The first, Hafzi Nela, fled to Yugoslavia and after being returned by the UDB at the request of the State Security, he ended up in prison and we were left with only three people in the group. After that, Shefqet was taken as a soldier in Tirana and only Avdi and Raif remained in the group. Given these circumstances in which we happened, the realization of the three variants we had thought of, became even more difficult. However, we did not stay in the context of words, as Shefqeti tried to do something about the assassination of Enver Hoxha, during the time he was a soldier in the anti-aircraft unit, in Koder Kamza, Tirana.

More specifically, what did Shefqeti do?

I am telling you that event, according to the chronology. In 1967, I came to Tirana by chance and went to meet Shefqet (uncle’s son) in Kodër – Kamëz, where he was a soldier, in an artillery regiment. After we talked for a long time in a club somewhere near the Institute, when we were parting, he instructed me to send him a telegram when I went to Kukës, that he allegedly had a sick mother, in order to come to Kukës with permission. I sent him the telegram and when Shefqeti came, he told me the whole story that had happened to him that day, when Enver Hoxha had gone on a visit to the terraces of Bathore. Prior to that visit, all security measures were taken by the military units, which were installed there, in the area around Koder – Kamza. Thus, it was done in the anti-aircraft unit, where Shefqeti served, based on the good biography he had (a brother “Martyr of the homeland”, father decorated for patriotic activities), being also the youth secretary of the unit, had been assigned to the main location, from where it seemed quite clear, the place where Enver Hoxha would visit. Shefqeti told me that during the moment he was at the scene and could see Enver Hoxha, he had raised his weapon, taking the target, but he had lowered it again, without being able to shoot. While Shefqeti started to tell me all the reasons why he could not shoot, to Enver Hoxha, I told him: “Let their arms be folded, why did you not shoot, what can be done. “If you had done that, you would have gone down in history, and we would all have been crushed.”

Who is Xhevat Gjana?

Xhevat Gjana was born in 1940 in Bicaj, Kukës, where his family comes from. During the years of Zog’s monarchy, almost the entire Gjana tribe was considered an opponent of that regime, as in the “June Revolution” in 1924 they had supported the fanatical forces by participating with weapons against government forces. Based on this fact, both of his uncles were sentenced to death. During the years of Nazi-Fascist occupation of Albania, 1939-1944, the Gjana tribe supported the National Liberation Movement and the house of his father, Bardh Gjana, became one of the main bases of the partisan movement in that province. But even though they had helped the Anti-Fascist War, with the coming to power of the communists after 1944, this family was targeted. This was due to the fact that their grandfather had served as a dervish and had a great influence on other members of the family and tribe, especially in terms of anti-communist ideas. Under these circumstances, at the beginning of 1948, the State Security would launch the first wave of arrests against members of the Gjana family, accusing them of being opponents of power and harboring members of anti-communist groups in the Kukes district. . Two of the main people arrested were his uncle Shaqir Gjana, and his nephew Kadriu. They would be released from prison only a few months later, during the “great turn of the Party” in 1949, when Enver Hoxha “blamed” all the crimes on the Minister of Internal Affairs, Lieutenant General Koci Xoxes. Xhevati, after finishing primary school in his village Bicaj, left for the city of Shkodra where he finished high school, and then the Pedagogical Institute in Mathematics-Physics. After graduating in 1963, he would serve as a teacher in the villages of Krumë, Domaj, and Topojan and in 1967, he would leave education, to serve for two years as an economist in the Copper mine in Gjegjan in Kukës. In 1969, Xhevati was arrested and after several months of investigation, he was convicted of “agitation and propaganda and acts of terrorism against the state”, in a group that included six other people. He was sentenced to 8 years in prison and served his entire sentence in Burrel prison, from where he was released in 1976. After his release from prison, Xhevat Gjana would work for the Bicaj cooperative in the Kukes district until 1980, when would leave for the city of Kruja. There he started a family with a girl from the Kuçi tribe, whose father had been shot by the communist regime, accused of being an “enemy of the people”. Until 1991, he would work as a worker in the State Construction Company of Kruja, while with the collapse of the communist regime, in the years 1992-1993, he would serve as Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Kukes district. After 1993, he would return to his family in Kruja and until 1997, he would serve as the director of the 8-year school, “Myrteza Pengili”. /Memorie.al