Part Four

Excerpts from the book: ‘ALIZOT EMIRI – The Man, the Library, and the Noble Wit’

A FEW WORDS AS AN INTRODUCTION

Memorie.al / When we, Alizot’s children, would tell “Zote’s” (Alizot’s) stories in joyful social settings, we were often asked: – “Have you written them down? No? What a shame, they will be lost…! Who should do it?” And we felt more and more guilty. If it had to be done, we had to do it. But could we write them?! “Not everyone who knows how to read and write can write books,” Zote used to say whenever he handled poorly written books. While discussing this “obligation” – the Book – among ourselves, we naturally felt our inability to fulfill it. It wasn’t a job for us! By Zote’s “yardstick,” we were incapable of writing this book.

Continued from the previous issue…

– IMPRESSIONS AND MEMORIES OF ALIZOT –

A conversation with the prominent writer, Dritëro Agolli

– “It’s not right for us, his children, to express such high praise for our father!” – I tried to justify the wording. They both insisted. We removed the epithet “simple,” but we children still hesitated to add adjectives. – “Let the memory of Alizot Emiri remain based only on the evaluations made by his friends and colleagues, without the natural over-praise of his children.”

Although we finished writing, the conversation continued naturally. It was the memory of Alizot’s turbulent life – full of clashes, accidents, challenges, and joys – that made Dritëro meditate and led Mrs. Sadie to find similarities in it.

We then talked about the “well-bred” (sojllinjtë) and the “ill-bred” (sojsëzët) who coexist in human society at all times, where the ill-bred ride on the backs of the well-bred and yet still complain, even though they are being carried. We talked about the heartbreaking ingratitude with which great favors, done with the kindness of the well-bred, are often repaid. – “Eeeeh…!!!”

It was a sigh well-earned! And in these moments, Sadie would go straight to the seated Dritëro, lean over him, take his face in her two hands, and kiss him on the forehead. She did this so naturally! My presence was no obstacle to this beautiful and very human ritual at their age. I admired this divine gesture more and more!

Precisely when a memory saddened Dritëro, as his distress grew, she – who followed his spiritual state with great attention – would go and kiss his forehead. It seemed to me as if that kind of contact was miraculous, and Dritëro would immediately find relief…!

This well-chosen gesture reminded me of the blessings our grandmothers and mothers gave us when we were little: “May I take your misfortunes upon myself!” (Ju maaarrsha të keqen!)

And I thought: Dritëro was very right to sing to Sadie, the Shkodran “sprite,” this guardian angel.

– “Bring us a glass each!” – Dritëro said. He wanted us to sip together, even though his 80 years of age had made his hand movements difficult. I felt more and more like a son of the house. The first glass was the glass of hospitality and respect. The second glass was for the conversation – it was for Alizot! At least I should resemble my father when it came to raki!

– “I’ve written some verses about what we discussed. I’ll find them,” said Dritëro, searching through papers…! – “Here, I think it’s this one:

The Great Humility

“No greater pain will you find, if you have seen

An honest man in misery and woe,

When he prays humble, with a heart so keen,

And expects help and hope from a scoundrel below.”

Eeh, what a pen would be needed to describe what I experienced! Certainly, I was the wrong person in the right place. In jotting down these lines, I felt not only incapable – which is fully justified – but also impolite for writing Dritëro’s name simply, without any titles like “Mr. Dritëro” or “Uncle Dritëro,” etc.

These titles have always made the names of elders more respected. They seem like the pedestal upon which monuments – the names of elders – are raised. And what majesty the pedestals give to monuments! Strangely, with Dritëro’s name, in my view, these kinds of titles do not constitute a pedestal at all! How is it possible? How can this be explained?

Perhaps because this name represents one of the highest mountains of national culture. You cannot place a mountain on a pedestal! The name DRITËRO carries the pedestal within itself!

IN THE FRONT RANK…!

-Second part of the conversation with Dritëro, Feb 9, 2011:

If there were a possibility to write a history of Albanian booksellers, I would place Alizot in the front rank. Why?

First, he knew the value of the book and the history of the book. In the history of human inventions, it is said that two great inventions came first: the invention of the wheel and the invention of the book. Nothing can move without a lever and a wheel in nature, and nothing can move in the mind without a book. Alizot knew these things; therefore, he had reverence and love for the book.

Second, as a result of the first, he did not see his bookstore – which was a small local shop – as an ordinary grocery or haberdashery, but as a cell, a core of culture. Everything inside that shop he knew like a home library – just as I have my library in a room where I know not only the value of the books but also their order on the shelves. Thus, when a book lover came to buy something, Alizot would explain the value of every shelf to them.

Now, in our days, it saddens me that there are no such booksellers. They look at a book as they look at a potato, a leek, a clove of garlic, or a shirt with a floral tie.

Third, Alizot looked at book buyers with the eye of a psychologist. For instance, he would guide a child or an old man toward the books that suited their categories, and at the same time, he did not offend them, but would say: “Take what you want, but what I am telling you come from experience.”

For adults, he wasn’t insistent on which books they should take; he only recommended. But for children, he was very careful, kind, and used a teacher’s tact, saying: “When you grow up, these books you are looking for will be very valuable to you.”

These thoughts I’ve shared, though a bit long, come from my acquaintance with Alizot since my youth and later.

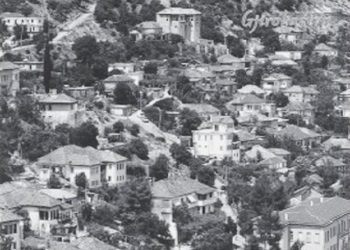

I thank you for making me remember Alizot, who was a close friend. Whenever I went on duty as a journalist to Gjirokastra, I never failed to meet him – in the bookstore, at the café, and on walks. He was, as I said at the beginning, one of the most pleasant men in conversation. He knew many stories and was an honest patriot.

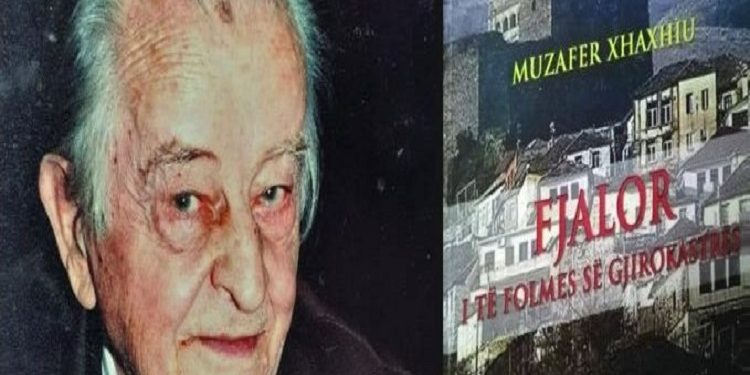

Prof. MUZAFER XHAXHIU: A LIFE LINKED TO THE BOOK

(Some memories of Alizot Emiri)

Among the many memories I have of the city of my childhood and youth, Gjirokastra, and its people, special impressions were left by that small bookstore located in the alley leading to Zigai’s large shop, from where you could go to the “Hazmurat” neighborhood. This was the only bookstore in the city, kept by Alizot Emiri – a renowned bookseller in Gjirokastra and a man of unique reputation.

I was young then, perhaps in primary school, when I first visited Alizot’s bookstore, which everyone in Gjirokastra called Zote. I loved books and enjoyed reading the stories and tales of the time.

I read with great relish and curiosity everything published at that time, which forced me as a child and later as a teenager to go often after school to Zote’s bookstore and dive into those shelves filled with books and magazines, mainly in the Italian language. I would find historical books, novels, and adventure stories there – though I don’t know where Alizot secured them to supply his shop.

Along with a classmate, Koço Miho – who later became a well-known architect in the city of Durrës – we would go often to Alizot’s bookstore and always find him in the company of a friend, laughing and telling stories we didn’t yet understand.

He welcomed us with a smile and allowed us to browse the shelves to find something beautiful for our age. He often guided us on what we should read. When we had no money to buy, he allowed us to read there in a corner and did not disturb us.

We would read, perhaps for hours, until we finished a fascicle of a book (back then many novels were published in fascicles, divided into parts), then we would leaf through an Italian magazine – a language we were learning in gymnasium. We would leave late, greeting and thanking him for all he did for us. He didn’t mind if sometimes we bought nothing, because he understood we couldn’t buy every new book we liked.

Zote’s brother, Myfit Emiri, was a classmate of mine in the gymnasium who worked with him in the bookstore. Both brothers cared for and kept the bookstore with the greatest passion. Myfit and I, being peers, hung out often; he was a lively and smart boy, spoke Italian very well, and had a desire to study and read. I also remember the father of these two brothers very well. He was a gentle, small-framed man called Braçe; being a postman, all of Gjirokastra knew him well.

The Emiri family lived in the “Palorto” neighborhood at the time, the same neighborhood where my family lived. During the war, a grave tragedy struck their family. When the Nazis entered Gjirokastra, many people fled to climb “Kucullë.” Meanwhile, the Nazis fired fiercely with mortars, and among the many victims of this attack, my friend and companion, Myfit Emiri, were killed.

I remember that both brothers were very good, loving, and educated people. Alizot was distinguished by a subtle and stinging humor. While I sat and read in his bookstore, I often heard boundless laughter, perhaps because Zote would tease a visitor who entered the shop. In the 1930s, his bookstore was a meeting place for many people, mainly the city’s intellectuals.

In 1938, when I was 17, I left Gjirokastra to continue gymnasium in Tirana. Years later, when I returned to my birth city as a mature man, among many acquaintances, I would also meet Alizot in his bookstore. The bookstore was now in a different place, on the road leading to Çerçiz Square, in the Qafa e Pazarit. I felt sad then that the bookstore of my childhood had not remained the same.

We would meet and talk with nostalgia, remembering the past, speaking about old and new books, the people, and the events of the city. Often, when I accompanied a foreign writer or professor to Gjirokastra, I would stop by Alizot’s and explain to the foreign guest that this person was the first and only bookseller of this beautiful and culture-loving city, and a well-known character throughout the town.

Alizot Emiri was a respected man throughout all of Gjirokastra, and everyone – young and old alike – knew him and his family. He was a loving and witty man, with a subtle and teasing humor that often required us, as children, to strain our minds to understand what he meant. He is still remembered as a respected man and a unique figure in the cultural life of the city of Gjirokastra. / Memorie.al

Tirana, December 2010

To be continued in the next issue